Maliseet

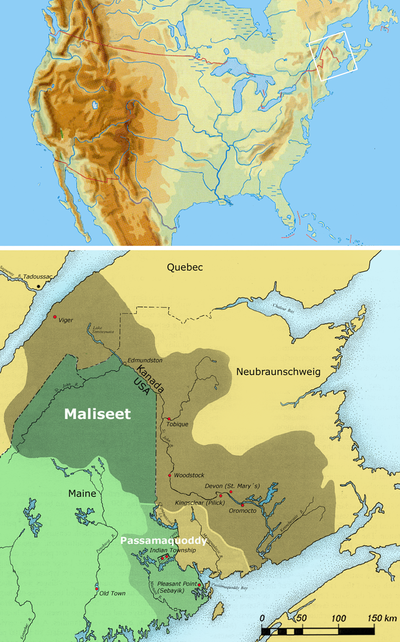

The Maliseet or Malecite , today increasingly Wolastoqiyik (formerly known as Étchemin by the French ), are a North American Indian - a tribe of the Algonquin language family in what is now the US state of Maine and the neighboring Canadian provinces of Québec and New Brunswick / Nouveau-Brunswick .

Linguistically they belong to the Eastern Algonquin and speak the northern dialect of the Malecite-Passamaquoddy (also Maliseet-Passamaquoddy ), a language whose southern dialect speaks the culturally and linguistically closely related Passamaquoddy .

Surname

The colonial French expression Étchemin was used as a collective term for the neighboring and related dialect-speaking peoples of the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy ( Peskotomuhkatiyik , singular: Peskotomuhkat ), therefore both peoples were often regarded as one ethnic group by early explorers . The origin of the name "Etchemin" itself is unknown, it probably comes from the language of the neighboring hostile Algonquin or Montagnais ( Muhtaniyik, Muhtaniyok , singular: Muhtani ). As members of the powerful Wabanaki Confederation , both peoples are also often referred to as Maritime Abenaki or Eastern Wabanaki , since the tribal areas of the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy are parts of the Canadian Maritimes (also Maritime provinces or simply the Maritimes ) - the eastern areas of the Confederation - included.

The tribal name most commonly used today as Maliseet (more rarely: Malecite ) is derived from Malesse'jik from the language of the neighboring and once hostile Mi'kmaq and means "slow speakers" or "broken speaking people" and refers to the different dialect of the Maliseet, which the Mi'kmaq found difficult to understand. Until the 20th century, the term Amalecites was a common French transliteration for the Maliseet in Québec ( called Kepek-ona in Malecite-Passamaquoddy ), while the names Milicite and Melicite were in use in New Brunswick . Early 20th century ethnographers chose Malecite , but today's Indians prefer “Maliseet”.

Their tribal areas Wolastokuk were in the catchment area of today's Saint John River , which the Maliseet call Wolastoq or Welàstekw ("beautiful river"), so the groups referred to themselves simply as Wolastoqiyik , Wolastokiwik , Welastekwíyek or Wulustukwiak ("people along the beautiful river, ie Saint John River ”). The Saint John River should not be confused with the St. Johns River in Florida . In addition, both - Maliseet and Passamaquoddy - simply referred to themselves as Skicinuwok ("(indigenous) people", "people", singular: Skicin ).

Residential area and environment

In 1603, Samuel de Champlain met some Maliseet warriors in the French trading post in Tadoussac . The Maliseet's first contact with Europeans, however, was more than 100 years earlier through Basque, Breton, Norman and Portuguese fishermen. The name Etchemin comes from Champlain . A year later he used the same name for residents at the mouths of the Saint John and St. Croix Rivers, claiming that the Etchemin extended from Saint John to the Kennebec River.

Since 1842, the border between Canada and the USA has hindered the unity of the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy groups, which show only slight cultural differences. The Maliseet were inland hunters and inhabited the St. John River basin in New Brunswick and Maine, while the Passamaquoddy were hunters of marine mammals and lived on the coasts of New Brunswick and Maine.

In terms of landscape, the former residential area of the Maliseet mainly consists of wooded, flat hills. The climate of the coastal areas inhabited by the Passamaquoddy is tempered by the Fundy Bay . The inland inhabited by the Maliseet does not have this moderating influence and has a more continental character. Sometimes there was not enough fish and game to meet the needs of the rather sparsely populated country. So at the end of the 17th century there was a real famine among some Maliseet groups.

Culture and way of life

Livelihood

The annual cycle, and with it the concern for livelihood, was based on the available food sources. In the spring, the Maliseet returned from winter camps to the central village to be the first to plant maize. In June they moved to one of the islands in the Saint John River and made camp there to spear perch and later sturgeon. In summer the Maliseet ate fish, wild grapes and edible roots of certain plants. In the autumn the corn was ripe; it was harvested, dried, and stored in underground pits that were covered with bark. In winter, groups of around 8 to 10 men each went on moose and bear hunts, crossing an area that spanned a large part of Maine, New Brunswick and the Gaspé Peninsula .

The Maliseet had a precise, seasonal hunting and gathering plan:

| January | Seal hunting |

| February March | Hunting beavers, otters, elk, caribou and bear |

| end of March | Fishing (fish that came up rivers to spawn) |

| end of April | Fishing for herring, perch, sturgeon, salmon and collecting Canada goose eggs |

| May to September | Cod fish and clams gather along the coast and bring in the ripening summer fruits |

| end of September | Eel catch |

| October November | Hunting beavers, bears and elk |

| in the middle of winter | Harpoon hunting in ice-covered waters for the spawning frostfish (Microgradus tomcodus) |

With the arrival of the Europeans, the Maliseet became increasingly dependent on the fur trade. Otters, beavers and muskrats were the main suppliers of fur, but moose skins were also traded. In the late spring, the Indians came to the trading posts, in later years to agreed collection points on the river, where the fur traders bought the catch.

At the request of the authorities, the Maliseet grew more potatoes and maize, but there was no success. They chose jobs as farm laborers, wood raftsmen, basket makers, guides for hunters and anglers or as stevedores on river boats. Many, however, continued the nomadic life, they camped near white settlements, went from house to house and sold their goods. Landing points for ferries and steamers turned out to be popular trading places. A good guide guaranteed his customers the hunt and the catch, making traditional unhindered winter hunting and trapping impossible. Today, many Maliseet live near white settlements, make chip baskets and trust in the charity of their white neighbors. In spring they collect violin heads , which are young fern fronds that sell well. Blueberries are picked in late summer and September to October is the busy time of the potato harvest, when many Indians from the region go to North Maine and the neighboring New Brunswick as harvest workers.

technology

The Maliseet were extremely skilled boat builders and presented a birch bark - Canoe ago which was brilliant adapted to the conditions in the many rivers of the residential area. It was light and easy to carry over the portages that interrupted the waterways. Birch bark was a widely used material among the Maliseet. They were used for containers such as boxes, baskets, buckets and dishes, and for the outer covering of the wigwam . The birch bark elk lure was an indispensable part of the hunting equipment. Birch bark served as rainwear, messages written on birch bark showed the traveler the way and the dead were buried in birch bark.

Chip baskets are made from the black ash and sold to tourists. The ornate basket made of colored ash shavings, often with plaited sweet grass in between, and a round base was made in earlier times. Making an ornate basket is women's work, while the men weave the simpler potato basket. In the past, ax handles, milk cans and other household items were also carved from the wood of the white ash . The sale of these wooden items ensured a livelihood for many Maliseet families, especially towards the end of the 19th century. In addition, snowshoes with a frame made of white ash and covered with caribou leather were made. The manufacture of snowshoes and toboggans used to be an important homework. Making and repairing potato barrels and potato baskets is still a source of income today.

Life cycle

Birth and upbringing

The birth took place with the help of some women outside the wigwam. The newborn was wrapped in beaver skins and tied to a cradle board . The male baby was often displayed urinating, even in winter, possibly causing the high mortality of these infants. The mother breastfed her child for two to three years. As long as the child was breastfed, the mother prevented or ended another pregnancy.

The freedom Indians allowed their children astonished contemporary French writers. The children learned through examples and imitation; if they made mistakes, they were warned but never beaten, but received a lot of affection and love. At an early age, she was asked to help her parents. The fathers made little paddles for their sons and daughters, who were skilled in canoeing by the age of ten. They were very adept at handling arrows and children's bows. As recently as 1835, young children were remarkably good archers, although adults no longer used bows and arrows at that time.

Girls learned early on those tasks that were important for their role in later life. They helped their mother with collecting firewood, cooking, making clothes, fetching water, assembling and dismantling the wigwam and carrying loads, because the women were largely responsible for moving a camp. When the son was around 12 years old, he first went hunting with his father and got a big bow. After killing his first moose, the boy was allowed to sit in council with the older men and attend public festivals.

Bridal service and marriage

When a young man had plans to marry, he asked his relatives and, in historical times, the Jesuits for a suitable girl. Often he followed the recommendation and went to her wigwam. If he liked it, he tossed a chip or stick into her lap, which she took and looked at the sender with a doubtful sideways glance. If she liked the young man, she tossed the chip back with a tentative smile.

Then the young man moved into his father-in-law's wigwam and had to do bridal service for at least a year . The future son-in-law was expected to help his father-in-law. He had to prove his skills by demonstrating his skill as a hunter. In addition to bows and arrows, he made a canoe and snowshoes. Meanwhile, his fiancée made clothes and shoes for him and covered his snowshoes. During this time, sexual relations with the fiancé were strictly forbidden. At the wedding supper, speeches and counter-speeches were held in which the ancestry of the groom was praised and the young man promised to surpass his ancestors. Afterwards there was a feast and the wedding day ended with dances.

The betrothed girl was subject to a strict moral code, which was continued after marriage through the fidelity of the married woman and there was seldom a divorce. Adultery was very unusual and used to be severely punished. These morals are also expressed in mythology.

End of life and burial

Special references to special burial customs of the Maliseet are sparse in the early literature. Shamans were brought in when someone became seriously ill, but they stopped trying to heal if they saw the case as hopeless. The dying person surrendered to their fate and was considered dead from that point on. The sick man was given nothing more to eat and cold water was poured over his body to hasten his death.

The Maliseet of the 20th century saw the custom of holding burials in the dead man's house. If this does not happen, it is believed that another person would die in the house where the funeral took place. Most of the Maliseet are devout Catholics. The preparatory rites last two to three nights, during which the deceased's house is filled with guests singing and praying the rosary.

Social organization

guide

The early chiefs were called Sakomak (singular: Sakom ) and were mostly of an advanced age. Supported by advisors, they led a band that mostly consisted of a related extended family or, more rarely, represented local groups (consisting of several extended families). The chiefs or sachems previously had little power and influence and could only make decisions through their prestige in agreement with all members of the community; only with the establishment and strengthening of the Wabanaki Confederation did they gain in importance. The organization of the Wabanaki Confederation required a strengthening of the chieftainship (which was now hereditary in the male line) in order to give stability to the leadership of the various allied tribes. If the chief did not have a son, or if the son was unsuitable for office, a nephew was usually chosen. In the 17th century, the Maliseet apparently had a chief who resided in the main village.

In addition to six peace chiefs ( Sakomak ), there were also war chiefs who were called Kinapíyek / Kinapiyik (singular: Kinap ). The Kínap was someone who had proven his ability and bravery in war and was able to successfully lead a troop of warriors ( Motapekuwinuwok , singular: Motapekuwin ) in an attack. The status of the Kinap was exclusively performance-oriented and could not be achieved through heredity or choice. There was also no set number of Kinapíyek, but usually only one chief in the tribe. Under pressure from the Bureau of Indian Affairs , a move was made in 1896 to elect a Maliseet chief for a three-year term.

Wabanaki Confederation

In the middle of the 18th century, the Maliseet formed together with the Passamaquoddy (in Malecite-Passamaquoddy: Peskotomuhkat , plural: Peskotomuhkatiyik ), the formerly hostile Mi'kmaq ( Mihkom , plural: Mihkomak ; hence once also known as Kotunolotuwok - "enemies") ), the Penobscot ( Panuwapskew , plural: Panuwapskewiyik, Panuwapskewihik ) and the two large regional tribal groups of the Abenaki ( Aponahkew , plural: Aponahkewiyik ) - the Eastern Abenaki and Western Abenaki - a political-military alliance against the so-called militarily strong Iroquois . Wabanaki Confederation (often incorrectly called the Abenaki Confederation ), referred to as Kci-lakutuwakon by the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy . This confederation included survivors of the once powerful Penacook Confederation and the Pocumtuc Confederation who had joined the Abenaki, as well as other tribes allied with the French later. Their central meeting place, called the Great Fire , was in Caughnawaga , Québec. Delegations from each participating group attended meetings (called Kci-mawe-putuwosuwakon ) in Caughnawaga three times a year and took part in various ceremonies. The use of the wampum as a memory aid was introduced by the Algonquians at this time. The Wabanaki Confederation was officially dissolved in 1862, but the five tribes remained close allies, and the confederation lives on to this day in the form of a political alliance between these historically friendly nations.

Their tribal area called the allied tribes as well as many neighboring Algonquin tribes Wabanaki ( land of dawn / twilight , ie land in the east ); it comprised areas of historic Acadia (today's Canadian maritime provinces of Nova Scotia , New Brunswick , Prince Edward Island ), the south of the Gaspésie Peninsula, and Québec south of the Saint Lawrence River in Canada and parts of New England (today's US states of Maine , New Hampshire , Vermont and Massachusetts ) in the northeastern United States .

The term Abenaki (or Abnaki ) is often incorrectly used synonymously for Wabanaki - however, the Abenaki were only a member of the Wabanaki Confederation. Because of the incorrect use of the word Abenaki for Wabanaki , all Abenaki along with the Penobscot were often called Western Wabanaki , while the Mi'kmaq, Maliseet and Passamaquoddy were called Eastern Wabanaki . The Maliseet designation for the Wabanaki is Waponahkiyik or Waponahkewiyik and for the shared territory Waponahkik .

The name Wabanaki is sometimes used collectively for all members of the confederation - so that an identification of the individual tribes is usually only possible in a geographical and historical context (if at all).

religion

Myths

There are extensive collections in which the myths of the Maliseet are documented. The traditional storytelling time started in autumn and ended at the beginning of spring. The most famous stories were summarized in the Kuloskap cycle and this cycle was told in Tobique until the 1940s. Even today, myths are told in some Maliseet families about witches and supernatural beings. Kuloskap, also Kelòskap, the hero and changer, was responsible for the creation of the natural wonders on the Saint John River and the transformation of the animals into their current form.

The myths of the Maliseet illustrate the follies of humanity and supernatural beings (gods, monsters, giants, spirits) represent the different character traits:

- Koluskap or Keluwoskap ("bearer of the great truth", in English mostly: Glooscap ; other variants: Glooskap, Gluskap, Gluskab, Gluskabe, Gluskabi, Kluscap, Kloskomba): was both trickster and cultural hero , master of transformation / deception, creator (from Animals and landscapes) and symbol of the good, a warrior against the evil in the world and in possession of great magical powers.

- Malsum or Malsom (" wolf ", in English mostly: Malsumis , other variants: Molsem, Molsum, Malsm, Malsumsa, Malsun, Mol-som, Malsumsis): Kuloskap's younger twin brother and representative of evil as well as in possession of great magical powers, as Opponent of Koluskap and creation (animals, plants and landscapes) as well as the gods, he reflects the other side of the highly ambivalent figure of the trickster and completes it.

- Mikcikc (" turtle ", in English sometimes also called Uncle Turtle , other variants: Mikcheech, Mikchich, Mikjikj, Mikjij, Mikji'j, Mikchikch, Miktcitc or Glamuksus, Chick-we-notchk, Cihkonaqc, Kcihqnaqc, Kcihknac): war another trickster figure and a shapeshifter as well as pranksters and mockers. According to legend, he was an awkward uncle of the cultural hero Koluskap. After a series of mishaps and attempts to win a woman, he transforms into the animal form of a turtle.

- Mahtoqehs (" snowshoe hare ", in English mostly: Great Rabbit , other variants: Mahtigwess, Mategwes, Máhtekwehs, Chematiquess): was another trickster figure - but with far less power, he is both a crook and a fool, is cunning and at the same time one Boobies and thus often causes annoyance and problems for others. Sometimes he dies because of his foolishness, only to then rise again. He is the main character in stories for children to explain these good and bad. He is never dangerous or malicious and is sometimes referred to as the Koluskap Friend.

- Mihkomuwehsis or Mikumwesu (other variants: Megumooweco, Mihkemwehso, Mekmues, Mikmues): In some Maliseet and Passamaquoddy traditions, it is a monster-killing dwarf and can also be viewed as evil. Most of the time, however, he is known as a thin man and an excellent archer who, due to his short stature , is easily overlooked by gods, heroes and people, can travel through the air and walk invisibly on earth; He is also heroic, good-natured and loyal and a constant friend of people and animals. He is the older brother and constant companion of Koluskap, has great magical powers like his brother, and is the progenitor of the "Little People", known as Mihkomuwehsisok or Mikumwesuck.

-

Mihkomuwehsisok or Mikumwesuck ("Kleinen Menschen / Little People", other variants: Mikumwesuk, Mihkomuwehsok, Mikumwessuk, Mekumwasuck, Mekumwasuk, Mihkomuwehsisok, Meckumasuck, Míkmwesúk, Mekemwasuk, Mikumweswak are people in small people or Mikumweswak) that are supposed to be about the size of a man's waist. They are generally benevolent forest spirits , but can be dangerous if not respected.

- Kiwolatomuhsis (plural: Kiwolatomuhsisok): A member of the “Little People”, of whom it was said that he secretly helped people with work (e.g., overnight) and whose breath smelled foul of mold.

- Wonakomehs or Wonakomehsis (plural: Wonakomehsuwok or Wonakomehsisok, in English mostly: Manogames , plural: Manogemasak ): Also a member of the "Little People", but since he lives along the rocky river banks or in the mountains, it is one Water spirit or mountain spirit (both are considered to be nature spirits ). Generally friendly, sometimes these canoes capsize, break fishing nets, or cause other mischief. The wonakomehsuwok have narrow faces and according to some traditions they are so thin that you can only see them in profile. When deposits of clay or mud along the river bank resemble people or animals, they are considered sculptures of the wonakomehsuwok and bring good luck to whoever finds them. Rocks on the bank of a river with geometric markings are believed to be the home of a wonakomehsuwok family and are best left undisturbed.

- Kiwahqiyik (singular: Kiwahq or Kíwahkw, in English mostly: Giwakwa , other variants: Kiwakw, Kewahqu, Kee-wakw, Kewok, Kewoqu, Kewawkqu ', Kewawkgu, Kiwakwe, Kiwákwe, Kiwa'kw, Keeiawahow', ', Keewahkwee): monstrous man-eating giants penetrating from the forests of the icy north into the land of the Maliseet ; these were also known as "ice giants" and were called Cinu or Chenoo ("rock giant" , other variants :, Jenu, Cenu, Chenu, Jinu, Djenu, Chinu, Cheno, Chenu, Tsi-nooPlural: Chenook). According to most legends, an "ice giant" was once a person who was either possessed by an evil spirit or committed a terrible crime (especially cannibalism or withholding food from a starving person) that turned his heart to ice. The strength of the Kiwahq is determined by the size of its heart of ice. Female Kiwahq are more powerful than their male counterparts.

- Kollu (plural: Kolluwok, in English mostly: Culloo , other variants: Klu, Kulloo, Kaloo, Cullo, Cullona, Kilu, Kulu, Gulu, Gulloua): A monster in the form of a giant bird of prey that ate people and was supposedly big enough to carry a child away with its claws.

Other stories are about cunning raids against the Mohawk.

Shamanism

The Maliseet healing methods are known from excellent early French sources. Accompanied by singing (Motewolonuwintuwakon, plural: Motewolonuwintuwakonol) the shaman blew over the affected part or the entire body. If his efforts did not achieve the desired result, the diseased area was sucked out or cut open.

The traditional belief in spirits and supernatural powers continues today and is far from extinction. A person who possesses supernatural powers is called Motewolon or Ptewolon (also: Metéwelen), a woman is called Motewolonisq or Ptewolonisq (also: Motewolonusq or Ptewolonusq). How a motewolon (shaman) gets his skills is unknown. He could have them from birth, for example if he is the younger of twins or the seventh son. Although this belief is believed to be of European origin, the seventh son of the seventh son is believed to be particularly powerful. The helping spirit in animal form is called ' Puwhikonol or' Puhhikonol (also: Pohíkan) and is sent in the form of a dream by the shaman to convey the corresponding message. Any physical injury to the puwhikonol is transmitted to the motewolon and only the person who injured the puwhikonol can heal the motewolon.

The motewolon cannot kill its Puwhikonol or hold it accountable. The Motewolon killed by an enemy cannot rot. But it does happen that he eats someone who comes too close. When the corpse has consumed three people, it becomes a Kiwahq or Kíwahkw (plural: Kiwahqiyik), a man-eating ice giant.

The Maliseet believe that some things contain supernatural powers or mana . Such objects, chosen for their bizarre appearance, are said to bring luck.

In addition, it was also the belief among the Maliseet Wahantoluhket : mostly shamans who were suspected (plural Wahantoluhkecik or Wahantolukhoticik) damage spells to practice or who have been placed under (after an unsuccessful attempt at recovery) to try to kill the sick in truth; these were mostly viewed by the community as sorcerers or witches.

Supernatural beings

The spirit world of the Maliseet consisted of supernatural beings of various kinds, which can be divided into three different categories:

- Social controllers

- Harbingers of events

- Sources of special skills

The stories about Aputamkon (plural: Aputamkonok, in English mostly: Apotamkin , further variants: Aputamkon, Appodumken, Appod'mk'n, Apodumken, Abbodumken, Apotampkin, Apotumk'n, Aboo-dom-k'n, Apotamkon, Apoatamkin, Aboumk'n), a giant sea snake with long red hair that lives underwater and pulls people, especially careless children, into the water and eats, is a good example of the first category. The stories about this sea monster were used by mothers to scare children into staying away from the water and to protect small children from ice that was too thin in autumn and from drowning in summer. The harbingers are innumerable and they have various names. Kisekepísit can appear as a premonition of death. A creature with a head and limbs is Cipelahq (plural: Cipelahqok, also: Kçipélahkw, associated with Thunderbird) and warns of impending calamity. A Maliseet from Woodstock became the Kéhtakws , whose calls could be heard whenever a storm hit. The Eskwetéwit fireball is an erratic harbinger of imminent death or tragedy. Dwarfs also appear in the spirit world of the Maliseet. The already mentioned Kiwolatomuhsisok (also: Kiwelatemohsísek) and the Wonakomehsuwok (also: Wonakomehsisok) are the creators of structures made of sand and clay on the banks of the rivers, through which one can predict the future, for example a small coffin-shaped object heralds death . The shavings of the horns of Wiwilomeq (plural: Wiwilomeqok or Wiwilomeqiyik, in English mostly: Weewillmekq , other variants: Wiwilmekw, Wiwilmeku, Weewilmekq, Wiwillmekq ', Wiwilameq, Wiwilemekw, Wiwila'mecq, Wewillemuck, Wiwiliameckq, Wiwiliamecku Wee-Will-l'mick, Wee-wil-li-ah-mek, Wee-wil-'l-mekqu '), a water monster (either as a giant snail or a giant water snake) consider the Maliseet to be a source of special power; possibly the Kci-Athussos ("big snake", in English mostly: Horned Serpent - "horned snake"), other variants: Kitchi-at'Husis, Kici Atthusus, Kichi-Athusoss, K'cheattosis, Ktchi at'husis , Atosis) meant a mythological giant, scaly, kite-like snake with horns and long teeth, found mostly in lakes and rivers, which has magical abilities such as shape change, invisibility or hypnotic powers and exercises power over storms and weather - people who Defeat or help the "Horned Serpent" receive powerful medicine from it.

music and dance

To accompany ritual dances, the Maliseet beat a board or used a drum and stag horn rattles filled with shotgun pellets to prompt the start of the dance. Other musical instruments were the flageolet and the flute. Before going to war there was a dance with prepared dog heads. Until about 1920, adult Maliseet performed show dances for white visitors.

Games

In the Altestáken game of chance , round bone slices were used as dice and a wooden bowl. It was still played in Kingsclear in the 1970s. Besides lacrosse , two other ball games were known, one resembling baseball , the other football . When the tribe got back together in the spring after the winter hunt, they played this slightly modified form of baseball. Since the 1920s, regular baseball became the Maliseet's most popular game. In the spring, there were also a number of sporting competitions, such as archery with betting on the outcome and races. In winter, people enjoyed the commercial dance , where objects were passed from person to person. The aim of the game was to get a worthless item to an unsuspecting crowd. A certain song was sung for this.

Popular medicine

Today's Maliseet do not differentiate between a Metéwelen and a homeopath , but believe that anyone with extensive knowledge of diseases and medicinal plants also has supernatural powers. The herbal doctor can be a man or a woman, and three or four people in a ward used to have reputations as herbalists. The knowledge about medicinal plants was passed on from the elderly to the younger ones with the appropriate skills. Herbalists were very reluctant to talk about their medicines because they lost their effectiveness when discussed with others. There are now extensive lists of Maliseet herbal remedies.

history

17th century

Although French and English explorers probably met them before, the first record of such contact is from Samuel de Champlain's 1604 trip. Fort La Tour, built on the Saint John River in the early 17th century, became the center of the tribe, in which they learned how to use firearms and other European devices. The early French settlers in this area mingled with the Maliseet, cementing their alliance with the French and their hostility to the English.

As a result of the increasing trade with the Europeans, there were considerable changes, especially in the material culture. Typical of the Maliseet were large summer villages, sometimes surrounded by palisades, and small, widely scattered winter settlements. In 1604, Champlain described the village of Quigoudi at the mouth of the Saint John River. There were countless small and large huts here that were inhabited by single or multiple families. A large house that served as the town hall even offered space for 80 to 100 people. The term huts could refer to both conical wigwams and rectangular houses that provided space for several families at festivities. Here, like a log cabin, a wall of four or five layers of tree trunks was built on top of each other and a roof made of birch bark, which was supported by posts. The beams and posts were connected with thin spruce roots or strips of cedar bark.

The largest Maliseet village was Meductic and was at a strategically important point at the end of the inland routes . Meductic was abandoned around 1767 and most of the residents moved to Aukpaque , which was first mentioned in 1733 and was near Fredericton . Aukpaque was now the main Maliseet settlement until the Indians lost it to loyalists in 1794 .

18th and 19th centuries

When the English had gained control of the Maliseet land, English settlement advanced rapidly and tensions arose with the indigenous people. The British established reservations from 1776 and wanted to re-educate the Maliseet to farmers. After the loss of Aukpaque, many families moved to the Kingsclear reservation . Originally about 65 km², Tobique became the largest of all Maliseet reserves in New Brunswick. Most of the Maliseet refused to become farmers but preferred nomadic existence as long as they could make a living from hunting and trapping and lived in a number of camps on the upper Saint John River.

In the treaty of 1794, the Maliseet were assured that they could move freely across the border between Canada and the United States, as their residential area was on both sides of the border. After the War of 1812 and the Treaty of Ghent , much of the Maliseet residential area was ceded to the United States by British Canada.

The Woodstock reservation was acquired by the New Brunswick government in 1851 to redress the injustice caused by the loss of Meductic. Two additional reservations were established in the Fredericton area in the second half of the 19th century. Increasing acculturation offered the Maliseet better earning opportunities in trades such as wooden rafts, boat loading and handicrafts. In 1867 the government bought 2.25 acres (9,100 m) in size in Devon for them . In 1928, an additional 328.5 acres (1.3 km²) were purchased in Saint Mary's nearby to make room for the growing population. The Oromocto Reserve was established in 1895 on a piece of land on which the Maliseet camped. In 1838 a reservation was granted on the two small islands The Brothers near the mouth of the Saint John River.

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Canadian government tried to concentrate the Maliseet on a few central reserves in economically more favorable areas. The Maliseet from the Saint Croix River moved to a reservation on the Saint John River. Many settlements, such as Apohaqui, Saint John, The Brothers, Pokiok and Upper Woodstock, have been abandoned by Native American families. The Maliseet also moved from the upper Saint John River to Aroostook County , Maine, because of the better income opportunities in the potato industry. Many Maliseets, including Passamaquoddy, moved to the industrial areas of Connecticut and Massachusetts , while the Maliseet in Québec married into French-Canadian families and largely adapted to French-Canadian society. Today there are no longer any pure-blood Maliseets because mixed marriages with Europeans have increasingly been concluded since the 17th century. Most of the Maliseet today grow up in the reserves and speak a little of their native language, but few are bilingual. Some older tribesmen still speak the Maliseet language, but this is less and less the case with young people.

Native American identity was reinforced with the establishment of the Union of New Brunswick Indians in 1967. With this action, the Maliseet merged with the Mi'kmaq and the cooperation between the two tribes brought significant progress. In 1969, the cooperation between Maliseet, Mi'kmaq and Passamaquoddy led to the non-profit association TRIBE , Teaching and Research in Bicultural Education (German: teaching and researching in bicultural education). This has significantly improved the educational opportunities of Indian youth in eastern Canada and Maine.

Today (March 2013) around 4,650 Maliseet live in New Brunswick and have formed the Madawaska Maliseet, Tobique, Woodstock, Kingsclear, Saint Mary's and Oromocto First Nations, in Québec the Première Nation Malecite de Viger has around 1,111 tribal members, the only one Maliseet group in the United States, the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians , has 800 tribal members.

Modern First Nations and tribes of the Maliseet

Union of New Brunswick Indians (UNBI)

- Kingsclear First Nation (also: Pilick First Nation , the First Nation is located near Fredericton on the Saint John River in New Brunswick, Reserves: Kingsclear # 6 (14 km west of Fredericton), The Brothers # 18 (2 small islands in Kennebecasis Bay , north of Saint John ), administrative seat: Fredericton, NB, population: 967)

Union of New Brunswick Indians (UNBI) and St. John River Valley Tribal Council (SJRVTC)

- Madawaska Maliseet First Nation (MMFN) (also: Matawaskiyak First Nation , sometimes also Première Nation Malécite du Madawaska (PNMM) , the First Nation is located in the middle of the Appalachian Mountains , near the city of Edmundston on the Saint John River in northwest New Brunswick, which is also the It forms the border with the USA in the south, the small town of Madawaska ( matawaskiye - “(water) it flows out over grass or reeds”) is located directly across from Edmundston on the south bank of the Saint John River, in the west the First Nation borders on Québec , reserves: St. Basile (1.6 km east of Edmundston), The Brothers # 18 (2 small islands in Kennebecasis Bay , north of Saint John ), population: 330)

- Woodstock First Nation (WFN) (also: Mehtaqtek First Nation or Wulustukwiak First Nation , the First Nation is located on the west bank of the Saint John River east of the city of Woodstock , south of Hartland and north of Fredericton in west New Brunswick, today's reservations are the Second settlement of this Maliseet band, from 1807 to 1851 they lived downstream near the former main settlement and at the same time the most important trading post of the Maliseet called Medoctec (also Meductic Indian Village / Fort Meductic , Medoktek , Madawamkeetook ) at the confluence of the Eel River and Saint John River, administrative headquarters: Woodstock, NB, Reserves: The Brothers # 18 (2 small islands in Kennebecasis Bay , north of Saint John ), Woodstock # 23 (5 km south of Woodstock), population: 950)

- St. Mary's First Nation (also: Sitansisk First Nation , the First Nation borders the city of Fredericton on the Saint John River in New Brunswick and is the largest Maliseet First Nation along the river, administrative headquarters: Fredericton, NB, reservations: Devon # 30 ( 6 km east of Fredericton), St. Mary's # 24 (6 km east of Fredericton, population: 1,756)

- Oromocto First Nation (also: Welamukotuk First Nation , the First Nation borders the city of Oromocto on the west bank of the Saint John River at the mouth of the Oromocto River , approx. 20 km southeast of Fredericton , New Brunswick, administrative seat: Oromocto, NB reservation: Oromocto # 26 (north and adjacent to Gegetown), population: 647)

Mawiw Council

- Tobique First Nation (CNB) (also: Negootkook First Nation , Neqotkuk First Nation or Wolastokiwik Negootkook , sometimes also: Première Nation de Tobique , the First Nation lies north of the Tobique River between the villages of Aroostook and Perth-Andover in northwest New Brunswick, their main settlement Tobique, approx. 45 km from Grand Falls, is called Neqotkuk or Negootkook , administrative seat: Tobique Narrows, NB, reservations: The Brothers # 18 (2 small islands in Kennebecasis Bay , north of Saint John ), Tobique # 20 (27 com south of Grand Falls), population: 2,185)

- Première Nation Malecite de Viger (also: Maliseet of Viger First Nation , the First Nation (or Première Nation ) is located in the valley of the Saint Lawrence River in Québec , in 1989 the Maliseet were recognized as the eleventh First Nation by the province of Québec, administrative seat : Cacouna # 22 (derived from Kakonang ), 16 km east of Rivière-du-Loup , QC, reservations: Cacouna # 22 (located in the County of Temiscouata, St. George-de-Cacouna, 193 km northeast of Québec ), Whitworth # 21 (180 km northeast of Québec, population: 1,111)

- Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians (HBMI) (also: Metaksonekiyak Band , lived and hunted along the Meduxnekeag River in northeast Maine, on the banks of which they now own small plots of land, now live in the vicinity of Houlton in Aroostook County , were on Federally recognized tribe officially recognized by the United States in October 1980, administrative seat: Littleton , Maine, population: 800)

Demographics

In 1612, the étchimin was estimated to have fewer than 1,000 members. The Maliseet and Passamaquoddy of the coastal region then suffered high losses from devastating European diseases, wars and possibly also from deliberate poisoning. Another decrease in population was recorded well into the 18th century, but by 1820 the Maliseet population had returned to 1612. A census from 1910 showed 848 Maliseets and since then the population has grown steadily, especially since many Maliseet only dared to identify as Indians in the second half of the 20th century and began to seek recognition as First Nations in Canada or as officially recognized Fight tribe in the US. Today (as of March 2013) there are around 8,750 Maliseets according to the official count.

Maliseet population around 1970

| reserve | all in all | within | outside |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edmundston | 67 | 47 | 20th |

| Kingsclear | 274 | 216 | 58 |

| Oromocto | 117 | 95 | 22nd |

| Saint Mary`s | 386 | 312 | 74 |

| Tobique | 617 | 437 | 180 |

| Woodstock | 258 | 123 | 135 |

Individual evidence

- ^ Passamaquoddy-Maliseet Language Portal

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians . Vol. 15: Northeast. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC 1978, ISBN 0-16-004575-4 , pp. 123ff.

- ^ Native Languages of the Americas: Glooscap Stories and other Micmac Legends

- ^ Website of the Union of New Brunswick Indians (UNBI)

- ^ Homepage of the Kingsclear First Nation

- ^ Website of the St. John River Valley Tribal Council (SJRVTC)

- ↑ Homepage of the Madawaska Maliseet First Nation (MMFN)

- ↑ The Brothers Reservation # 18 is shared by the following Maliseet First Nations: Kingsclear First Nation, Madawaska Maliseet First Nation, Woodstock First Nation, Tobique First Nation

- ↑ Home page of the Woodstock First Nation

- ^ Homepage of St. Mary's First Nation

- ^ Homepage of the Oromocto First Nation

- ↑ ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: Mawiw Council homepage )

- ^ Homepage of the Première Nation Malecite de Viger

- ^ Homepage of the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians

literature

- Bruce G. Trigger (Ed.): Handbook of North American Indians . Vol. 15: Northeast. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC 1978, ISBN 0-16-004575-4 .

Web links

- Maliseet

- Maliseet language

- Micmac Language

- Malecite Indian History ( Memento from June 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- Passamaquoddy - Maliseet Dictionary