Geta (emperor)

Pushkin Museum , Moscow

Publius Septimius Geta (born March 7, 189 in Rome ; † December 19 or 25/26, 211 there ) was Roman Emperor from February 4, 211 until his death . He belonged to the Severian dynasty and was co-regent of his older brother Caracalla ; At times he was given the first name Lucius.

Geta and Caracalla were the two sons of the founder of the dynasty, Septimius Severus , who made them co-rulers and prepared them for their common succession. After the death of their father, on February 4, 211, they succeeded as planned. Their common rule failed that same year due to the deadly rivalry between them. Caracalla lured Geta into a trap and had him murdered.

Origin and youth

Originally from Africa, Septimius Severus, who had made a career in Rome and various provinces, married the distinguished Syrian Julia Domna in 187 . On April 4, 188, the couple's first son, Caracalla, was born. At that time Severus was in Lugdunum, today's Lyon , as governor of the province of Gallia Lugdunensis . After this governorship ended, the family moved to Rome. Geta was born there on March 7, 189. He received the name of his paternal grandfather, the Punic Roman knight Publius Septimius Geta . Severus took over the office of governor of Upper Pannonia in 191 , but his children stayed in Rome. On April 9 of the " second year of the four emperors" in 193, Severus was proclaimed emperor by the army in Pannonia. The following year he prevailed in the civil war against rival Pescennius Niger .

Between Geta and his brother Caracalla, who was only eleven months older, there was already a pronounced rivalry in early youth, which in the further course of their lives steadily intensified and turned into deadly hatred. The primacy of the older brother was clearly expressed through names and titles in both of their childhood and youth. From the spring of 195, Septimius Severus pretended to be the adopted son of the popular emperor Marcus Aurelius, who died in 180, in order to legitimize his rule . Caracalla was therefore considered to be the fictional grandson of Mark Aurel and received his name from 195/196: From then on he was called Marcus Aurelius Antoninus , and like his father was considered a member of Mark Aurel's family, the imperial family of the Antonines. Geta, on the other hand, was given the first name Lucius for a time, which should perhaps be reminiscent of Lucius Verus , the co-regent of Mark Aurel, but was not fictitiously included in the Antonine family by renaming. Even then, this showed a preference for his one year older brother. Perhaps as early as the middle of 195 or 196 at the latest, Caracalla was given the title of Caesar, designating him future emperor. A corresponding increase in Getas ranked initially failed.

In 197 Geta accompanied his father with Caracalla on his second campaign against the Parthians . Perhaps as early as 197, or 198 at the latest, he received the titles Caesar and Princeps iuventutis . At the same time Caracalla was raised to Augustus , that is, to the nominal co-regent of the emperor. With this, Caracalla's precedence was again established. The imperial family stayed in the Orient for some time; In 199 she traveled to Egypt, where she stayed until 200. She did not return to Rome until 202. From 202 to 203 the family stayed in North Africa; she probably spent the winter in Severus' hometown of Leptis Magna in Libya .

Severus tried in vain to soften the enmity between his sons and to cover it up from the public. Imperial propaganda feigned unity: Concordia (unity) coins were minted, and in 205 and 208, Caracalla and Geta jointly held the consulate. A prolonged absence of Rome's two rivals seemed desirable in order to avoid scandals in the capital. This is probably one of the reasons why Severus took both sons with him when he set out on a campaign to Britain . The fight was directed against the Caledonians and Mäats living in what is now Scotland . In 209 Geta was given the dignity of Augustus , and was therefore treated as equal to his brother in this respect. This set the course for future common rule; Severus must have recognized that this was the only way his younger son had a chance to survive the impending power struggle.

The fighting in Britain dragged on. Since Septimius Severus was in poor health, he entrusted Caracalla with the sole direction of military operations. Geta, on the other hand, received no command, but took on purely civilian tasks. Nevertheless, both sons took on the winning name Britannicus maximus , which Severus also used. Severus died on February 4, 211 in Eburacum (now York ).

Empire and death

After the death of Severus, his sons came to power together as intended, although the title of Pontifex Maximus Caracalla was reserved; Geta only remained pontiff . Although Caracalla was able to claim a certain priority again, this does not seem to have been clear enough to clarify the balance of power. But since Geta was popular with the soldiers, Caracalla did not dare to openly take action against him at first. The two emperors made peace with the Caledonians and Mäaten and returned to Rome with a separate court . There both of them protected themselves from one another by careful guarding. The common rule of Mark Aurel and his adoptive brother Lucius Verus in the period 161 to 169 and that between Mark Aurel and his son Commodus from 177 to 180 served as a model for this constitutional construction . However, at that time the difference in rank and the division of tasks between the emperors were more clearly regulated, while Caracalla and Geta, who were both the biological sons of an emperor, lacked a clear, amicable regulation of the hierarchy, powers and responsibilities.

A dual empire of rulers with equal rights would have required a division of the empire under the given circumstances. The historian Herodian claims that dividing the Roman Empire and assigning Geta to the east was actually considered, but this plan was rejected because Julia Domna, mother of the two emperors, strongly opposed the plan. This report is, however, doubted by several ancient historians; Attempts to find confirmation of this in epigraphic material have in any case failed.

A tense and very unstable situation had arisen in Rome. The Roman city population, the Praetorians and the troops stationed in the capital and its surroundings were divided or indecisive, so that a civil war seemed imminent. It is unclear whether there were regionally different preferences among the provincial troops. According to a controversial research hypothesis, Geta's supporters were strong in the east of the empire, while Caracalla found support above all from the border troops in the Rhine and Danube region.

In December 211 - not, as was previously suspected, not until February 212 - Caracalla managed to lure his brother into an ambush. At his suggestion, Julia Domna invited her two sons to a reconciliation talk in the imperial palace. Geta recklessly accepted the mother's invitation, believing that he would be safe from his brother in her presence. The sequence of the fatal encounter, which took place either on the 19th or on the 25th and 26th December took place is unclear. According to the account of the contemporary historian Cassius Dio , which is believed to be the most credible, Caracalla ordered murderers who killed his brother in the arms of the unsuspecting mother, injuring her hand. Apparently he also struck himself, because later he consecrated the sword he had used in the Serapeion of Alexandria to the deity Serapis, who was worshiped there .

Caracalla, who had achieved sole power by eliminating his brother, justified the act by claiming that he had only anticipated one attack by Geta. After the murder, he had numerous people killed who were believed to be Geta's supporters. Cassius Dio names the perhaps exaggerated number of 20,000 victims of the slaughter. Many who were accused of sympathizing or mourning their defeated rivals also died later. Even Julia Domna was not allowed to mourn her son.

iconography

The identification of Geta portraits is difficult in some cases, it is possible that the young Geta could be confused with Caracalla, who is almost the same age. A large part of Geta's portraits probably fell victim to systematic destruction after his death, as the damnatio memoriae (erasure of memory) was imposed on him. Cassius Dio mentions that Geta was very much like his father as an adult.

In the beginning, classical archeology differentiated only two types of portraits from Geta as heir to the throne. The first of them, referred to as the “first type of prince”, is assigned to the period 197 / 198-204, from the elevation to Caesar to Geta's first consulate. These include twelve replicas of a round sculpture that can be clearly assigned to Geta; they belong to the "Munich-Toulouse type". According to this classification, the "second type of prince" began in 205. It is characterized by a striking, almost twin-like resemblance between Geta and Caracalla, which was politically wanted in the context of the unity propaganda.

A further differentiation could later be made on the basis of the coin portraits, which may be due to the better location of the coins compared to the plastic. Seven types of portraits can be distinguished on the coins. The first six are defined by increasing beard growth; they correspond to the simultaneous coin portraits of Caracalla and aim at a similarity between the two brothers, who should both be shown to the people as heir to the throne. The seventh and last type of portrait Getas, on the other hand, shows him after the death of his father, clearly in contrast to the portrait of his brother with a long, shaggy beard, which remained the same during this period, very similar to the deceased father, probably with the aim of portraying Geta as the true heir to the throne .

reception

After Geta's death, Caracalla sought the complete erasure of the memory of his brother. As part of the damnatio memoriae imposed on Geta , the eradication of his name in all public monuments and documents was carried out with the greatest thoroughness; even its coins were melted down. The body is said to have been cremated. Later, after Caracalla's death, Geta's aunt Julia Maesa , Julia Domna's sister, arranged for her to be buried in the tomb of the imperial family, the Hadriani mausoleum . Caracalla's grave was also there.

When the resentment of the urban population in Alexandria was directed against Caracalla, its critics also referred to the murder of Geta.

The main sources are the historical works of the contemporaries Cassius Dio and Herodian , written after Caracalla's death . Cassius Dio writes from the perspective of the senatorial opposition to Caracalla. He paints an unfavorable picture of Geta; Both Caracalla and Geta were rapists and pederasts and embezzled funds during their father's lifetime . He describes Geta's pitiful demeanor in the face of death dramatically. Despite Cassius Dio's very partiality, his Roman History is considered the best source and is relatively reliable. Herodian's account is more imprecise and flawed. It contains different information about Geta's character. At one point Herodian claims that Geta's character, like Caracalla, was spoiled by the luxurious life in Rome, at another point, where he compares the two, he portrays Geta as (relatively) gentle and measured, kind and philanthropic.

The biographies of Getas and of Septimius Severus and Caracallas in the Late Antique Historia Augusta are of lesser importance . They are considered to be relatively unreliable. The Historia Augusta depends in part on the two older works, but its author must also have had access to material from another contemporary source that is now lost. He describes Geta as greedy and selfish, but capable of pity and not unscrupulous.

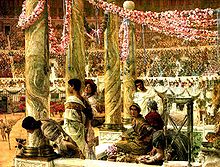

In 1907, after almost two years of work , Lawrence Alma-Tadema completed the oil painting "Caracalla and Geta". It shows the imperial family - Geta with his brother and parents - in the Colosseum .

literature

General

- Géza Alföldy : The fall of the emperor Geta and the ancient history . In: Géza Alföldy: The crisis of the Roman Empire. History, historiography and consideration of history . Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-515-05189-9 , pp. 179-216

- Matthäus Heil : (P.) Septimius Geta . In: Prosopographia Imperii Romani , 2nd edition, part 7/2, de Gruyter, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-11-019316-9 , pp. 171–174 (S 454)

- Florian Krüpe: The Damnatio memoriae. About the destruction of memories. A case study on Publius Septimius Geta (189–211 AD). Computus, Gutenberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-940598-01-1

- Barbara Levick : Julia Domna. Syrian Empress . Routledge, London 2007, ISBN 0-415-33143-9

iconography

- Klaus Fittschen , Paul Zanker : Catalog of the Roman portraits in the Capitoline Museums and the other municipal collections of the city of Rome . Volume 1, 2nd, revised edition, Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1994, ISBN 3-8053-0596-6 , text volume p. 100–105, table volume Tafeln 105–109 (No. 87–90)

- Florian Leitmeir: "I will not buy Geta's bust" - news on the typology of the portraits of the Severan princes Geta and Caracalla . In: Münchner Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst 58, 2007, pp. 7–22

- Heinz Bernhard Wiggers : Geta . In: Heinz Bernhard Wiggers, Max Wegner : Caracalla, Geta, Plautilla. Macrinus to Balbinus (= Max Wegner (Hrsg.): The Roman image of rulers , section 3, volume 1). Gebrüder Mann, Berlin 1971, ISBN 3-7861-2147-8 , pp. 93-114

- Andreas Pangerl: Portrait types of Caracalla and Geta on Roman Empire coins - definition of a new Caesar type of Caracalla and a new Augustus type of Geta. In: Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt des RGZM Mainz 43/1, 2013, pp. 99–116

Tools

- Attilio Mastino: Le titolature di Caracalla e Geta attraverso le iscrizioni (indici) . Editrice Clueb, Bologna 1981 (compilation of the inscribed evidence for the title)

Web links

- Literature by and about Geta in the catalog of the German National Library

- Michael L. Meckler: Short biography (English) at De Imperatoribus Romanis (with references).

- Geta's biography in the Historia Augusta (English translation)

Remarks

- ↑ This dating is the predominant one in recent research, see Anthony R. Birley : The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, extended edition, London 1988, p. 218 and Barbara Levick: Julia Domna , London 2007, p. 32 and note 71. Florian Krüpe represents a different date (May 27, 189): Die Damnatio memoriae , Gutenberg 2011, pp. 13, 177.

- ↑ Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, p. 5 and note 22.

- ^ Helga Gesche : The divinization of the Roman emperors in their function as legitimation of rule . In: Chiron 8, 1978, pp. 377-390, here: 387f .; Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, p. 9 and note 34; Anne Daguet-Gagey: Septime Sévère , Paris 2000, pp. 255f .; Drora Baharal: Victory of Propaganda , Oxford 1996, pp. 20-42.

- ↑ Bruno Bleckmann : The Severan family and the soldier emperors . In: Hildegard Temporini-Gräfin Vitzthum (ed.): Die Kaiserinnen Roms , Munich 2002, pp. 265–339, here: 270. It could also be a matter of adopting the first name of Septimius Severus. Evidence from Attilio Mastino: Le titolature di Caracalla e Geta attraverso le iscrizioni (indici) , Bologna 1981, p. 36.

- ↑ Florian Krüpe: The Damnatio memoriae , Gutenberg 2011, p. 182f. and note 48.

- ^ For spring 196, Matthäus Heil pleads: Clodius Albinus and the civil war of 197 . In: Hans-Ulrich Wiemer (Ed.): Statehood and Political Action in the Roman Empire , Berlin 2006, pp. 55–85, here: 75–78. Another opinion is u. a. Helmut Halfmann : Itinera principum , Stuttgart 1986, p. 220; he advocates mid-195.

- ↑ ILS 8916.

- ↑ On the dating approaches see Helmut Halfmann: Itinera principum , Stuttgart 1986, p. 51; Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, p. 10; Anthony R. Birley: The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, p. 130.

- ↑ On the ranking, see Fleur Kemmers : Out of the Shadow: Geta and Caracalla reconsidered . In: Stephan Faust, Florian Leitmeir (Ed.): Forms of Representation in Severan Time , Berlin 2011, pp. 270–290, here: 271–274.

- ↑ Florian Krüpe: The Damnatio memoriae , Gutenberg 2011, p. 178.

- ↑ On the trip to Africa and its dating see Anthony R. Birley: The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, pp. 146-154.

- ↑ Illustration in Barbara Levick: Julia Domna , London 2007, p. 81. Cf. Daría Saavedra-Guerrero: El poder, el miedo y la ficción en la relación del emperador Caracalla y su madre Julia Domna . In: Latomus 66, 2007, pp. 120-131, here: 122f.

- ↑ For the dating see Anthony R. Birley: The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, p. 274; Michael Louis Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, p. 13, note 58.

- ↑ Barbara Levick: Julia Domna , London 2007, p. 84.

- ↑ See Fleur Kemmers: Out of the Shadow: Geta and Caracalla reconsidered . In: Stephan Faust, Florian Leitmeir (eds.): Forms of Representation in Severan Time , Berlin 2011, pp. 270–290, here: 271, 283–285.

- ↑ Herodian 4,3,5-9.

- ^ Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprising and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, p. 63; Géza Alföldy: The Crisis of the Roman Empire , Stuttgart 1989, pp. 190–192, 213f.

- ↑ Jenö Fitz comes to this conclusion : The behavior of the army in the controversy between Caracalla and Geta . In: Dorothea Haupt, Heinz Günter Horn (Hrsg.): Studies on the military borders of Rome , Vol. 2, Bonn 1977, pp. 545–552; see. Markus Handy: Die Severer und das Heer , Berlin 2009, pp. 105–110. Fitz is rejected by Julia Sünskes Thompson: Uprisings and protest actions in the Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, pp. 62–64 and Géza Alföldy: The Crisis of the Roman Empire , Stuttgart 1989, pp. 215f.

- ↑ For the dating see Helmut Halfmann: Two Syrian relatives of the Severan imperial family . In: Chiron 12, 1982, pp. 217-235, here: 229f. and note 49 (for December 19); Michael L. Meckler: Caracalla and his late-antique biographer , Ann Arbor 1994, pp. 15, 109-112 (for December 25); Anthony R. Birley: The African Emperor. Septimius Severus , 2nd, expanded edition, London 1988, pp. 189, 218 (for December 26th); Florian Krüpe: The Damnatio memoriae , Gutenberg 2011, pp. 13, 195–197; Géza Alföldy: The Crisis of the Roman Empire , Stuttgart 1989, p. 179.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 2.2-4; see. Géza Alföldy: The Crisis of the Roman Empire , Stuttgart 1989, pp. 193–195. When specifying some of the books of Cassius Dio's work, different counts are used; a different book count is given here and below in brackets.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 23.3. Compare Herodian 4,4,3.

- ↑ It has been suspected that it was Caracalla's portrait rather than Geta's that was accidentally deleted; see Heinz Bernhard Wiggers: Caracalla, Geta, Plautilla . In: Max Wegner (Ed.): Das Roman Herrscherbild , Division 3 Volume 1, Berlin 1971, pp. 9–129, here: 48. This hypothesis, however, did not prevail; see Florian Krüpe: Die Damnatio memoriae , Gutenberg 2011, p. 237.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 2.5-6.

- ^ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 1.3.

- ^ Klaus Fittschen, Paul Zanker: Catalog of the Roman portraits in the Capitolinische Museen and the other municipal collections of the city of Rome , Volume 1, 2nd, revised edition, Mainz 1994, text volume pp. 100-102; Heinz Bernhard Wiggers: Geta . In: Heinz Bernhard Wiggers, Max Wegner: Geta (= Max Wegner (Ed.): The Roman Ruler Image , Section 3 Volume 1), Berlin 1971, pp. 93–114, here: 97–103; Florian Leitmeir: "I will not buy Geta's bust" - news on the typology of the portraits of the Severan princes Geta and Caracalla . In: Münchner Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst 58, 2007, pp. 7–22; Florian Leitmeir: Breaks in the emperor's portrait from Caracalla to Severus Alexander . In: Stephan Faust, Florian Leitmeir (Eds.): Forms of Representation in Severan Time , Berlin 2011, pp. 11–33, here: 14f., 23f .; Eric R. Varner: Mutilation and Transformation. Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture. Leiden 2004, p. 169 f.

- ↑ Andreas Pangerl: Portrait types of Caracalla and Geta on Roman Empire coins - definition of a new Caesar type of Caracalla and a new Augustus type of Geta . In: Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt des RGZM Mainz 43, 2013, 1, pp. 99–116.

- ↑ For the extraordinary consistency in the implementation, see Florian Krüpe: Die Damnatio memoriae , Gutenberg 2011, pp. 14–16, 198–244; Heinz Bernhard Wiggers: Geta . In: Heinz Bernhard Wiggers, Max Wegner: Geta (= Max Wegner (Hrsg.): The Roman Emperor Image , Section 3 Volume 1), Berlin 1971, pp. 93–114, here: 93f. See Eric R. Varner: Mutilation and Transformation. Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture , Leiden 2004, pp. 168, 170-184.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 79 (78), 24.3. Cf. Barbara Levick: Julia Domna , London 2007, p. 145.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 22.1; Herodian 4,9,2-3.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 77 (76), 7.1.

- ^ Cassius Dio 78 (77), 2.3.

- ↑ For an assessment of the sources see Julia Sünskes Thompson: Aufstands und Protestaktion im Imperium Romanum , Bonn 1990, p. 11 and the literature cited there.

- ↑ Herodian 3,10,3.

- ↑ Herodian 4, 3, 2-4.

- ↑ Helmut Halfmann: Two Syrian relatives of the Severan imperial family . In: Chiron 12, 1982, pp. 217-235, here: 230f.

- ↑ Historia Augusta , Geta 4.1-5.2.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Septimius Severus |

Roman Emperor 211 |

Caracalla |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Geta |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Publius Septimius Geta; Lucius Septimius Geta |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Co-regent of the Roman emperor Caracalla |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 7, 189 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Rome |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 211 |

| Place of death | Rome |