Greek language question

The dispute over the question is referred to as the Greek language question ( Greek γλωσσικό ζήτημα glossiko zitima ( n. Sg. ), Short form το γλωσσικό to glossiko ( n. Sg. )), Also [new] Greek language question or [new] Greek language dispute, whether the modern Greek vernacular ( Dimotiki ) or the classical high-level language ( Katharevousa ) should be the official language of the Greek nation. It was held in the 19th and 20th centuries and in 1976 it was decided in favor of the vernacular, which has been the official language in Greece ever since .

overview

The concept of the language question was created in the 19th century in analogy to the oriental question . While this was the determining foreign policy topic of Greece in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the language question describes the great domestic political challenge of the Greek state over many decades. The fundamental divergence between two independent varieties in the Greek language has existed since the first century BC. The phenomenon, also known as Greek diglossia , only became explosive with the Neo-Greek Enlightenment in the last decades of the 18th century, when the awakening of the modern Greek national consciousness was accompanied by questions of identity and the intellectual paving of the establishment of the state. The Greek language dispute spanned a period of around 185 years (from the end of the 18th century to 1976) and had a decisive influence on literature, education and everyday public life in Greece. It is not a purely academic debate, but a partly ideologically motivated and often bitter dispute, the effects of which directly affected most Greeks and which caused deaths at its culmination point.

Dimotiki and Katharevousa

The terms Dimotiki (vernacular) and Katharevousa (pure language) can be found in individual writings (Kodrikas 1818 and Theotokis 1797) at the beginning of the language question, but did not become more widespread until the end of the 19th century; before that there was more talk of archéa ( αρχαία , the "old", that is, the one based on ancient Greek) and kathomiluméni ( καθομιλουμένη , the "spoken" language). Behind the terms "Dimotiki" and "Katharevousa" there are not two clearly defined and standardized complementary languages, but a broad spectrum of language variants that are more or less based on the spoken vernacular or ancient Greek and, depending on one of the two parties, were roughly assigned .

In the first decades of the linguistic dispute, the term Katharevousa referred to a specific form of standard language developed by Adamantios Korais ; in later phases of the dispute and still today, it is used across the board for almost all language variants that were not based on the spoken language but were more or less based on ancient Greek. Individual personalities who took a position on the question of language even demanded the abolition of the Katharevousa, as this was not high enough for them, and instead the revival of the pure Attic language - this shows that standard language and Katharevousa are not always synonymous terms. From a scientific point of view, it is therefore advisable for the period from around 1835 to use the term high-level language over that of Katharevousa .

The linguistic background of the problem

While the Dimotiki was the natural mother tongue of the Greeks, the Katharevousa was an artificial high-level language that was pronounced in modern Greek, but was based on ancient Greek grammatically and lexically and sought to reintroduce numerous linguistic phenomena that the vernacular had lost over time. These include:

- Morphological phenomena: In its strict form, the Katharevousa still contained the ancient Greek dative , numerous participles and several additional tenses and conjugation schemes for the verbs .

- Phonological phenomena: The Katharevousa contained - since it was based on ancient Greek, although pronounced in modern Greek - some difficult-to-articulate letter combinations that were originally foreign to the modern Greek sound system, for example φθ [ fθ ], σθ [ sθ ], ρθρ [ rθr ], ευδ [ ɛvð ].

- Syntactic phenomena: While the vernacular consisted mostly of simply constructed sentences, in the Katharevousa the ancient Greek syntax was often used to create long and complex sentences that seemed as learned as possible.

- Lexical phenomena: The representatives of the standard language discarded numerous popular Greek words as well as foreign words that modern Greek had taken over over the centuries from other languages, mainly Latin , Venetian and Turkish , and replaced them either with ancient Greek words (for example ἰχθύς ichthys or ὀψάριον opsarion instead of ψάρι psari - fish ) or by neologisms (see below).

Taken as a whole, these differences meant that the Katharevousa was not or only partially understandable for the average Greek without a higher education.

Text examples

Example to illustrate diglossia

For someone who has no knowledge of Greek himself and whose mother tongue (for example German) there is no phenomenon comparable to Greek diglossia, it is difficult to understand the background to the Greek language dispute. This is because it is a matter of the coexistence of two - in the extreme case - fundamentally different forms of language, which go far beyond the stylistic gradient between written and spoken language that exists in every language. Nevertheless, the attempt should be made here to reproduce a short, strongly high-level text and its translation into popular modern Greek in two forms in German: once in a constructed, extremely learned high-level language (as a counterpart to extreme Katharevousa), and once in simple, spoken German (as a counterpart to Dimotiki). This is a child's written New Year's greeting to their parents:

|

|

Two texts by Greek writers

"Καὶ ὑμεῖς, ὦ ἂριστοι, ἐξ ὧν ὑμῖν ἐχαρίσατο, οὐχὶ διά τινος εὐτυχοῦς διορύξεως ὁ Ἑρμῆς ὁ τυχαῖος καὶ ἄλογος, ἀλλὰ διὰ τῆς ἐχέφρονος καὶ ἐπιμελοῦς καὶ ἐπιπόνου ἐμπορικῆς πραγματείας, ὁ Ἑρμῆς ὁ μετὰ τιμιότητος ...»

«Καθαρέβουσα γιὰ ποιὸ λόγο λὲν τὴ γλῶσσα τους οἱ δασκάλοι; Γιατὶ ὅλα τὰ κάμνει ἄσπρα σὰν τὸ χιόνι, παστρικὰ σὰν τὸ νερὸ. »

Historical development

Early development of diglossia

As early as the first century BC, the emergence of two different writing styles in Greek-speaking countries became apparent: While on the one hand the Alexandrian koine was the naturally developing, popular Greek mother tongue , some scholars, the so-called Atticists , began to use Attic Greek in their writings to imitate classical times. This was with the numerous achievements of the 5th century BC. In philosophy, statecraft and other areas and was considered noble, whereas the simple language of the people, which had undergone great phonetic, morphological and syntactic changes within a few centuries and was already clearly different from ancient Greek (more precisely from the Attic dialect of ancient Greek) , was increasingly perceived in learned circles as vulgar and not worth writing. However, this initially did not lead to any disputes, as the official language of the state was always regulated and was not in doubt. Although the drifting apart of popular and standard language hardened into a permanent diglossia, this state of affairs was tacitly accepted for centuries, since there was at most a problem of literary expression, but no impairment of everyday life. While the vernacular was spoken and written, the high-level language based on the Attic ideal was limited to the written use of the few scholars.

The Greek Enlightenment

In the 17th century, isolated voices were heard for the first time, which problematized the coexistence of two different Greek language varieties and criticized one of the two. However, an actual discourse did not begin until the end of the 18th century, when Eugenios Voulgaris (1716-1806), Lambros Photiadis, Stefanos Kommitas and Neofytos Dukas as representatives of a scholarly style of language, and Voulgaris' pupils Iosipos Moisiodax (1725-1800) and Dimitrios Katartzis (approx. 1725–1807) advocated a simpler language and expressed their views. Even Rigas Velestinlis (1757-1798), Athanasios Psalidas (1767-1829) and the poet Ioannis Vilaras (1771-1823) and Athanasios Christopoulos (1772-1847) voted for the language of the people. At that time (1765–1820) the Greek Enlightenment thinkers were fundamentally concerned about the origin and identity of the modern Greek people and were confronted with the practical question of which language the Enlightenment of the nation could or should use. In the longer term, these thoughts resulted in the consideration of what should be the uniform language of the still-to-be-founded modern Greek state.

Korais and the first violent arguments

"We write for our Greek compatriots today, not for our dead ancestors."

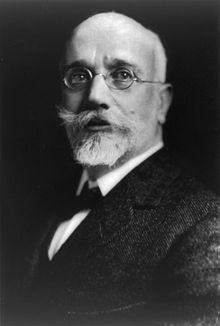

The decisive influence on the further development exercised Adamantios Korais (1748–1833), who was basically on the side of the vernacular, but wanted to refine it and purify it of particularly "vulgar" elements. Korais, who had a number of comrades-in- arms in K. Kumas, N. Vamvas, Theoklitos Farmakidis and others, believed the problem on this “middle path” ( μέση οδός mési odhós , 1804) between the purely popular and the strictly ancient Greek ideal-oriented way of thinking to be able to solve and went down as the inventor of the Katharevousa (literally: the pure [language] ) in the history of Greek language. Korais had a bitter pamphlet dispute with Panagiotis Kodrikas, an extreme representative of the high-level language, which was the first sad climax in the Greek language question. While Korais believed that poets and philologists should become the spiritual leaders and educators of the nation, Kodrikas wanted the power elite to play this role. The language question already had clear extralinguistic, political features, and the arguments of many participants revealed a connection between linguistics and morality: the decline of Greek culture had led to a barbarization of thought and language; if one were to correct the language now, that would automatically result in an ennobling of morals.

The foundation of the new Greek state

After a war of independence lasting several years , the new Greek state was founded in 1830; The capital was initially Nafplio , from 1834 Athens . The Katharevousa prevailed as the official language of the state , as the less prestigious, "unpolished" vernacular was considered unsuitable for meeting the requirements of a modern state; In addition, the establishment of a learned high-level language should build on the glamor of bygone times. However, there was no official norming and standardization of the Katharevousa, so that even more archaistic variants of the high-level language continued to exist and gradually prevailed over the moderate Katharevousa of a Korai.

As a result, the high-level language , which is increasingly based on the literary Koine and Attic, was established for a long time not only as the official language, but also as the language of instruction in Greece, with the result that children at school no longer express themselves freely in their mother tongue were allowed to. Even for adults without a higher education, communication with state institutions such as authorities or courts was made more difficult, since all written applications and documents had to be written in high-level language and could therefore only be drawn up by paid clerks.

The marriage of high language

The high-linguistic movement became increasingly independent and radicalized, oriented itself more and more towards a purist , backward-looking atticist ideal and, in addition to growing religious intolerance and disputes over the theses of Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer , had a decisive influence on intellectual and social life in the 1850s.

The Phanariotes , a kind of Greek intelligentsia around the patriarchate in Constantinople at the time of the Ottoman Empire and the young Greek state , were a group of conservative, noble scholars who stood on the side of the antiquated high-level language and appeared as opponents of the vernacular. Panagiotis Soutsos, who wrote in an increasingly ancient high-level language and became one of the most important representatives of Athenian romanticism, like his brother Alexandros, also came from the phanariotic tradition and in 1853 went so far as to demand the abolition of what he saw as the less archaic Katharevousa and its re-creation to proclaim the pure ancient Greek language.

Folk-linguistic poets such as Athanasios Christopoulos (1772–1847) and Dionysios Solomos (1798–1857), who lived and wrote on the Ionian islands that were not integrated into the Greek kingdom until 1864 and were not affected by the linguistic archaization of the intellectual life of Athens , took a completely different path . But there was nothing they could do about the fact that half a century after the founding of the state, the age of Athenian romanticism, became the wedding of the Katharevousa, in which the language question was hardly discussed. Numerous high linguistic neologisms created, which should replace the corresponding popular words such as γεώμηλον jeómilon (literally Erdapfel ) instead πατάτα patata (potato) or ἀλεξιβρόχιον alexivróchion (literally umbrella ) instead ομπρέλα ombréla (inherited from Italian word for umbrella ). Many of these neologisms have meanwhile disappeared again, but many others are now an undoubted part of the modern Greek language, for example ταχυδρομείο tachydromío (Post) .

The most radical manifestations of Attic archaism can be classified in the 1850s and again around 1880 with Konstantinos Kontos. It was only in the last quarter of the 19th century that the vernacular gained a slight prestige, as the work of the historians Konstantinos Paparrigopoulos and Spyridon Zambelios brought the question of the continuity of Greek history more to the fore and thereby achieved a greater appreciation of modern Greek traditions and dialects has been. Dimitrios Vernardakis, who, like Kontos, was a professor of classical philology at the University of Athens, recommended that the vernacular should be freed from all high-level words grafted onto it, but he wrote his recommendation himself in high-level language. With the participation of two famous linguists, Giannis Psycharis (1854–1929) on the part of the Dimotiki and the founder of modern Greek linguistics , Georgios N. Chatzidakis (1848–1941), on the part of the language taught, the Greek language problem gradually approached its climax .

The "linguistic civil war" around 1900

Psycharis' Manifesto "My Trip" ( Το ταξίδι μου To taxidi mou , 1888) was with his radical, highly regularized ideas of the vernacular the Demotizismus new impetus, busy discussing the language issue and rang three decades of bitter, yes partially civil strife to the language in Greece. The dispute had finally left the boundaries of academic pamphlets and learned study rooms and was taking on ever larger dimensions in public.

Representatives of the Katharevousa insulted demoticists as " μαλλιαροί " (long-haired) , " ἀγελαῖοι " (herd animals) and " χυδαϊσταί " (vulgar speakers ) , while the followers of the vernacular reverse their opponents as " γλδωσverter) " ( ρεοτς : γλωσvertiger ) , ( ρεοτς : in γλωσvertiger ) , spiritual darkness living ), " ἀρχαιόπληκτοι " (antiquated) , " μακαρονισταί " (= imitators of an exaggerated antique style) or " συντηρητικοί " (reactionaries, conservatives) . The high-linguistic purists also accused the demoticists of Bolshevism and Pan-Slavism , while they believed themselves to be the true heirs of ancient Greece. The sad climax of this development were the riots that took place in response to the translation of the Gospels (1901) and the translation and performance of the Oresty (1903) into the modern Greek vernacular, which even resulted in deaths and the resignation of Theotoki's government. While some wanted to establish the vernacular as the natural national language in all areas and saw themselves as the executor of a modern Greek process of emancipation and maturity, others were indignant about the blasphemy and decadence , which in their eyes translated the word of God or time-honored tragedies into vulgar language of the mob . The education system was still in a terrible state and completely ineffective: The children had great difficulty in expressing themselves in the unfamiliar standard language and were therefore not encouraged but rather inhibited in school. Only the girls' school in Volos stands out from the dreary educational landscape in Greece at the beginning of the 20th century: The liberal pedagogue Alexandros Delmouzos established Dimotiki as the language of instruction there and was able to achieve successes such as significantly increased performance and joy in learning on the part of the students. Such a liberal approach was a thorn in the side of conservative and clerical circles, however, and they protested so massively against the “modern mores” of the girls' school in Volos that the school had to be closed and Alexandros Delmouzos was convicted of immorality.

First successes of the liberals

Only with the establishment of the "Society for Education" ( Εκπαιδευτικός Όμιλος , 1910) could moderate-liberal circles around Manolis Triantafyllidis , Alexandros Delmouzos and Dimitrios Glinos that as much from the Katharevousa as extreme Dimotiki-positions as the Psycharismus demarcated, a Achieve partial success. Article 107 of the Greek Constitution, adopted on February 11, 1911, stated:

“The official language of the state is that in which the constitution and the texts of Greek legislation are drawn up. Any action aimed at corrupting this language is prohibited. "

The then Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos declared himself a demoticist and pointed out that the unclear wording of the article allowed an interpretation that the Dimotiki also tolerated (one only had to write laws in the Dimotiki, then the article would be sufficient and the Dimotiki de facto official state language), he also anchored the vernacular from 1917 to 1920 for the first time as the language of instruction of the three lowest elementary school classes. In the end, however, these actions remained a drop in the ocean, as laws were in force until 1975 that made a wider use of the vernacular difficult. Article 107, which has also entered modern Greek historiography as the “great compromise” ( μεγάλος συμβιβασμός ), remained a disappointment for supporters of the vernacular. After all, the Katharevousa visibly lost its extreme attic characteristics and came closer to the vernacular again.

The language question after the First World War

In 1917 the Dimotiki first found its way into the Greek educational system when it was declared the language of instruction in primary schools; In the following decades, however, it was pushed back several times by the Katharevousa. The situation, however, remained unchanged in the case of higher schools and in general the entire state administration, the courts, the universities, the army and the church, where the standard language was still the only official language. Only gradually did the Dimotiki succeed in gaining influence outside of primary schools in the state, for which the linguist Manolis Triantafyllidis (1883-1959) did crucial work. An important milestone on the way to the state emancipation of the vernacular was Triantafyllidis' grammar of modern Greek ( Νεοελληνική γραμματική [της δημοτικής] , 1941), which has been translated for decades and is still considered to be the standard work of modern Greek linguistics.

The end of the language dispute

In 1964, the Center Party in Greece declared Dimotiki and Katharevousa to be school languages on an equal footing for the first time, but higher levels of education remained de facto still under the unbroken influence of the standard language. The military dictatorship (1967–1974) finally declared the Katharevousa to be the official language again in 1967 and pushed the Dimotiki back to the first four years of school. Even after the military dictatorship in 1975, the Greek constitution did not contain any reference to the official state language; The era of state linguistic purism in Greece did not end until April 30, 1976, when the Karamanlis government and Education Minister Rallis made Dimotiki the sole language of instruction. A few months later a circular about the use of the Dimotiki was added in all public pronouncements and documents, heralding the end of a centuries-old diglossia. Significantly, however, the legal text to establish the vernacular was still drafted in Katharevousa. In 1982 the polytonic spelling was finally abolished and the monotonic system , which only knows one accent, was made mandatory for schools. Today the vernacular is the official language of Greece (as well as Cyprus and the European Union ), although numerous lexical, grammatical and phonetic elements of the Katharevousa have found their way into everyday language and enriched the Dimotiki in a way that is now less problematic. The language dispute no longer plays a role in Greece these days; only the Greek Orthodox Church continues to use standard language in official documents and in the liturgy and does not recognize vernacular translations of the Bible as official. Visitors to the monastic state of Athos are still given a residence permit, which is written in extremely high-level language. In addition, there are a few university professors who give their lectures in Katharevousa and particularly praise the students' work in high-quality language.

The language question in literature

Numerous writers expressed themselves implicitly or explicitly in their writings on the Greek language question; After all, they were affected by linguistic status issues and rigid state language policy and directly influenced in their work. The literary development in Greece that is taking place parallel to the language dispute cannot of course be described as a system that is completely decoupled from politics, but some aspects of literary history deserve to be presented separately.

Athenian and Ionian School

After the founding of the state in 1830, two major, different lines can be recognized in the Greek literary landscape over several decades: On the one hand, the Athens School (Athenian Romanticism) around Panagiotis and Alexandros Soutsos, which was strongly influenced by the Phanariots in Constantinople, centered in the new capital Athens was and largely conveyed the pure-linguistic and neoclassical character of the young state from the 1840s onwards in literature; on the other hand, the Ionian School of the Heptanesian poets around Dionysios Solomos and Aristotelis Valaoritis, who used their local, vernacular dialect as a written language and whose home islands did not initially belong to the modern Greek state and were therefore not exposed to the spiritual pull of the capital Athens. The latter - such as the national poet Solomos (whose hymn to freedom was elevated to the Greek national anthem ) - are among the most important modern Greek poets today, while the representatives of the Athens School enjoy a not nearly as great literary status. In the 19th century, however, Katharevousa initially prevailed as the official literary language in Greece. The poetry competitions from 1851 to 1870 only allowed Katharevousa as the only language of poetry. The linguistic change that some writers of the Athens School, such as Panagiotis Soutsos or Alexandros Rizos Rangavis, made is interesting: They began with the Dimotiki and ended in the strict archaic form. Rangavis, for example, revised his own story Frosyni ( Φρωσύνη ) in 1837 by archaising it linguistically.

Language satires

Some writers parodied the question of language in their works, for example by juxtaposing figures with extremely antiquated and completely exaggerated expressions with representatives of the simplest people. Famous satires related to languages are from the period of Greek enlightenment, for example, The Dream ( Το όνειρο not clarified Author) The learned travelers ( Ο λογιότατος ταξιδιώτης by Ioannis Vilaras, published in 1827) or the comedy Korakistika ( Τα κορακίστικα of Iakovos Rhizos Nerulos 1813). But even much later, when the Dimotiki were gradually beginning to emancipate themselves, writers satirically referring to the language problem. For example Georgios Vizyinos , who in his work " Διατί η μηλιά δεν έγεινε μηλέα " (1885) ironically reports how as a little schoolboy he was not allowed to use the "normal" word for apple tree ( μηλιά miljá ) in the presence of his teacher , but rather to corresponding Katharevousa form ( μηλέα miléa ) was forced and beaten if violated. Also Pavlos Nirvana expressed in his linguistic autobiography ( Γλωσσική αυτοβιογραφία , 1905), in which, as in Vizyinos the ratio of the real autobiographical and fictional content is unclear satirically on language problem by in-person narrative describing the career of a young man who more and more succumbs to the fascination of high-level language and rises to become an extremely atticizing scholar. Even if only a few understand his learned speech, he is admired for his ability to express himself. It was only when he met some beautiful girls from the people that he had doubts about his linguistic view of the world, because instead of ῥῖνες rínes , ὄμματα ómmata , ὦτα óta and χεῖρες chíres - in German for example: heads, faces , face oriels ... - he suddenly only saw in his mind her delicate μύτες mýtes , μάτια mátja , αυτιά aftjá and χέρια chérja - completely "natural" noses, eyes, ears and hands - and subsequently turns away from the delusion of high-level language.

The victory of the vernacular in literature

Towards the end of the 19th century, more and more writers turned to the vernacular, and especially since the generation of 1880 , the triumph of the vernacular in literature was unstoppable. While prose works were initially still written in Katharevousa, but with dialogues in Dimotiki (e.g. the stories by Georgios Vizyinos and Alexandros Papadiamantis ), from the 1880s onwards, poetry said it was technically and scientifically creative, but lyrically weak , ossified Katharevousa. Above all, Kostis Palamas (or Kostas Krystallis ) plays a leading role in establishing the vernacular in poetry. From around 1910 to 1920 prose followed suit. Almost the entire literary work in Greece in the 20th century finally took place in the vernacular, admittedly with more or less pronounced high-level linguistic influences and refinements; individual avant-garde writers always resorted to the Katharevousa, such as the surrealists Andreas Embirikos and Nikos Engonopoulos . Critics of the generation of the 1930s criticized the poetry of Kostas Karyotakis for the fact that it was not written in “pure” vernacular, but rather contained high-level words.

Résumé

The question of which form of language ultimately emerged victorious from the long dispute is extremely interesting. Even though Dimotiki has been legally established as the only language in Greece for over 30 years, this question cannot be answered unequivocally in its favor. Not only do numerous high-level words and language structures live on in modern Greek today; science today also tends to answer the old question of whether ancient Greek and modern Greek are one and the same or two completely different languages by saying that they are more one language than two. In a suitable context, Homeric words could also be used today that “do not exist” in modern Greek. With this view, which postulates a Greek language pool that has continued since Homer, the representatives of the standard language, who, in contrast to the demoticists, always denied the existence of a modern Greek language completely different from ancient Greek, would be indirectly confirmed posthumously.

As an important result, it can also be stated that the language dispute did not have exclusively negative consequences: “But one should not get a wrong picture of the situation, because the development of Greek in the 20th century (and especially in its second half) is a excellent proof that this struggle for the language of land and society in the 19th and 20th centuries Century caused damage, but at the same time forced the emergence of a conflict that had lasted for several centuries; He accelerated a process of coming of age, through which the vernacular basis grew together with the high-level elements, which led to a common language ( Νεοελληνική κοινή / Standard Modern Greek) that is perhaps more powerful and expressive than ever before. "

literature

- Francisco R. Adrados : History of the Greek Language. From the beginnings till now. Tübingen / Basel 2002. (On the topic of the language dispute, especially pages 286–290)

- Margaret Alexiou : Diglossia in Greece. In: W. Haas (Ed.): Standard languages, Spoken and Written. Manchester 1982, pp. 156-192.

- Georgios Babiniotis (Γεώργιος Μπαμπινιώτης): Λεξικό της νέας ελληνικής γλώσσας. 2nd edition. Athens 2002 (with an encyclopaedic explanation of the language question under “γλωσσικό ζήτημα” on p. 428).

- Robert Browning : Greek Diglossia Yesterday and Today. International Journal of the Sociology of Languages 35, 1982, pp. 49-68.

- Hans Eideneier : On the medieval prehistory of the modern Greek diglossia. Work on multilingualism, episode B. Hamburg 2000.

- C. Ferguson: Diglossia , Word 15, ISSN 0043-7956 , pp. 325-340.

- A. Frangoudaki (Α. Φραγκουδάκη): Η γλώσσα και το έθνος 1880–1980. Εκατό χρόνια για την αυθεντική ελληνική γλώσσα. Athens 2001.

- Gunnar Hering : The dispute about the modern Greek written language. In: Chr. Hannick (Ed.): Languages and Nations in the Balkans. Cologne / Vienna 1987, pp. 125–194.

- Christos Karvounis : Greek (Ancient Greek, Middle Greek, Modern Greek). In: M. Okuka (Hrsg.): Lexicon of the languages of the European East. Klagenfurt 2002, pp. 21-46.

- Ders .: Greek language. Diglossia and Distribution: A Cultural-Historical Outline.

- MZ Kopidakis (MZ Κοπιδάκης) (Ed.): Ιστορία της ελληνικής γλώσσας. Athens 1999.

- G. Kordatos (Γ. Κορδάτος): Ιστορία του γλωσσικού μας ζητήματος. Athens 1973.

- Karl Krumbacher : The problem of the modern Greek written language. Munich 1903 (= speech at the public meeting of the Royal Bavarian Academy of Sciences in Munich, 1902).

- A. Megas (Α. Μέγας): Ιστορία του γλωσσικού ζητήματος. Athens 1925-1927.

- Peter Mackridge : Katharevousa (c. 1800–1974). An Obituary for an Official Language. In: M. Sarafis, M. Eve (Eds.): Background to Contemporary Greece. London 1990, pp. 25-51.

- Ders .: Byzantium and the Greek Language Question in the nineteenth century. In: David Ricks, Paul Magdaliano (Eds.): Byzantium and the Modern Greek Identity. Aldershot et al., 1998, pp. 49-62.

- Johannes Niehoff-Panagiotidis : Koine and Diglossie. Wiesbaden 1994 (Mediterranean Language and Culture: Monograph Series, v. 10).

- E. Petrounias: The Greek language and diglossia. In: S. Vryonis (Ed.): Byzantina and Metabyzantina. Malibu 1976, pp. 195-200.

- Linos Politis : History of Modern Greek Literature. Cologne 1984, pp. 20-24.

- Giannis Psycharis (Γιάννης Ψυχάρης): Το ταξίδι μου. Athens 1888.

- E. Sella-Maze: Διγλωσσία και κοινωνία. Η κοινωνιογλωσσολογική πλευρά της διγλωσσίας: η ελληνική πραγματικότητα. Athens 2001.

- Michalis Setatos (Μιχάλης Σετάτος): Φαινομενολογία της καθαρέυουσας. ΕΕΦΣΠΘ 12, 1973, pp. 71-95.

- Arnold J. Toynbee : The Greek Language's Vicissitudes in the Modern Age. In: ders .: The Greeks and their Heritages. Oxford 1981, pp. 245-267.

- Manolis Triantafyllidis (M. Τριανταφυλλίδης): Νεοελληνική Γραμματική: Ιστορική Εισαγωγή , Άπαντα, Volume 3. 2nd edition. Thessaloniki 1981.

- E. Tsiaouris: Modern Greek: A Study of Diglossia. Doctor Thesis, University of Exeter, 1989.

- AG Tsopanakis (Α.Γ. Τσοπανάκης): Ο δρόμος προς την Δημοτική. Μελέτες και άρθρα. Thessaloniki 1982.

Remarks

- ↑ cf. Babiniotis (2002), p. 428

- ↑ cf. Karvounis (2002), p. 15

- ↑ See the chapter "The Marriage of High Language"

- ↑ German native speakers in Switzerland probably have it easier here, since the coexistence of Standard German and Swiss German in Switzerland is also a form of diglossia.

- ↑ The Katharevousa original comes from Pavlos Nirvanas ( Γλωσσική Αυτοβιογραφία , 1905, p. 15) (as an exaggerated, unmasking extreme form of Katharevousa in a completely inappropriate context ); the other three versions were made by the author of the article.

- ↑ So many authors. Karvounis (2002) mentions the end of the second century BC.

- ↑ Since Alexander the Great the Attic ancient Greek, in the Byzantine Empire initially Latin , since Emperor Herakleios again the standard Greek language, cf. Karvounis (2002), p. 8.

- ↑ On the origin of atticism and the controversial question of when one can speak of a real diglossia, cf. Christos Karvounis: Greek Language. Diglossia and distribution: a cultural-historical outline and the same. (2002), pp. 4–11

- ↑ So Babiniotis (2002), p. 428. Politis (1984), p. 21, already lists Nikolaos Sophianos at the beginning of the 16th century as the first scholar to become aware of the language problem.

- ↑ This epoch is commonly referred to as the Greek Enlightenment, see Karvounis (2002), p. 15.

- ↑ cf. on the Greek enlightenment especially Politis (1984), pp. 77-87.

- ↑ Adamantios Korais: Ελληνική Βιβλιοθήκη. Paris 1833, p. 49 f.

- ↑ Kodrikas, for example, called for the purely ancient Greek ἰχθύς ichthýs instead of the vernacular word ψάρι psári (fish) , while Korais had suggested the late ancient form ὀψάριον opsarion , cf. Adrados (2002), p. 287

- ↑ cf. Karvounis (2002), p. 13. Politis (1984), p. 141, writes: “The Katharevousa, the creation of scholars, is gradually becoming the official state language”, which suggests that a selective and official decision in favor of the Katharevousa is not took place, but that this asserted itself in the first years of the state. M. Alexiou (1982), p. 186, writes on the other hand: Korais' Katharevousa “was eventually established as the official language of the Greek State in 1834.”

- ↑ cf. Karvounis (2002), p. 15

- ↑ cf. Notes in another footnote

- ↑ cf. Karvounis (2002), p. 16, and Alexiou (1982), p. 187

- ↑ cf. Adrados (2002), p. 288

- ↑ cf. Karvounis (2002), p. 16

- ↑ cf. Babiniotis (2002), pp. 427f. and Karvounis (2002), p. 16

- ↑ see. Adrados (2002), p. 288. The question of a possible Slavic (partial) identity of the modern Greek nation has been a much discussed topic at least since Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer (1790–1861); he had speculated that the ancient Greeks had died out by the Middle Ages and were replaced by Slavic peoples. According to this, today's Greeks are only Hellenized Slavs and Albanians . Since the representatives of the Katharevousa saw the popular language, which was full of Turkish, Slavic and Italian foreign and loan words, a threat or vulgarization of their millennia-old Greek identity, they sometimes completely wrongly equated the Demoticists with Pan-Slavists.

- ↑ cf. Karvounis (2002), p. 17

- ↑ L. Politis (1984), p. 21, wrote around 1980: “Even if the Katharevousa is not to blame for all our misfortune, as the first demoticists claimed in their overzealousness, it is nevertheless responsible for the ominous fact that a graduate of the Greek grammar school is still not able to write correctly and express himself clearly in his language [...] even today [at the end of the 1970s]. "

- ↑ cf. Anna Frankoudaki (Άννα Φρανκουδάκι): Ο εκπαιδευτικός δημοτικισμός και ο γλωσσικός συμβιβασμός του 1911. Ioannina 1977, p. 39

- ^ Greek. ψυχαρισμός , named after the radical demands of Giannis Psycharis

- ↑ Quoted from Frankoudaki (1977), p. 41

- ↑ cf. Alexis Dimaras ( Αλέξης Δημαράς ): Εκπαίδευση 1881–1913. In: Ιστορία του ελληνικού έθνους , Volume 14 ( Νεότερος ελληνισμός, από το 1881 ως το 1913 ). Athens 1977, p. 411

- ↑ cf. Adrados (2002), p. 288

- ↑ According to Karvounis (2002), Katharevousa was reintroduced as the language of instruction in elementary schools in 1921–1923, 1926, 1933, 1935–1936 and 1942–1944, cf. P. 18. Babiniotis (2002), p. 428, however, writes that the vernacular has never lost its primacy in elementary schools since 1917. According to Adrados (2002), p. 289, the Dimotiki was only abolished in primary schools during the reign of C. Tsaldaris (1935–1936).

- ↑ see Aristotle University of Thessaloniki ( Memento of August 25, 2004 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Νεοελληνική Γραμματική (της δημοτικής). Ανατύπωση της έκδοσης του ΟΕΣΒ (1941) με διορθώσεις. Thessaloniki 2002, ISBN 960-231-027-8 .

- ↑ cf. Adrados (2002), p. 289. Politis (1984), p. 23, on the other hand, writes that the Dimotiki was pushed back to the first three years of primary school.

- ↑ cf. Karvounis (2002), p. 18

- ↑ cf. e.g. Babiniotis (2002), p. 428

- ↑ However, some publishers and individuals continue to use the polytonic system for linguistic or aesthetic reasons. The question of the correct setting of accents is and has always been of much less relevance than that of the language itself; Accordingly, the emphasis is now handled freely and flexibly; see Modern Greek orthography .

- ↑ For example the Byzantinists Athanasios Kominis and Stavros Kourousis from the University of Athens in 1997.

- ↑ Corfu, for example, was never under Ottoman rule and only passed from the United Kingdom to Greece in 1864.

- ↑ cf. Karvounis (2002), p. 16

- ↑ Politis (1984), p. 145

- ↑ cf. Politis (1984), pp. 87f.

- ↑ Georgios Vizyinos (Γεώργιος Βιζυηνός): Διατί η μηλιά δεν έγεινε μηλέα. In: Τα διηγήματα , Athens ²1991

- ↑ Pavlos Nirvanas ( Παύλος Νιρβάνας ): Γλωσσική αυτοβιογραφία. Athens 1905

- ↑ In German, the coexistence of high-level and vernacular expressions for everyday things like body parts can unfortunately not be adequately reproduced in many cases. An example that at least approximates the diglossia situation discussed here in German would be the expression “head” for “head”, “face” for “face” or “face hole” for “nose”; Literally, however , the ancient Greek expressions mentioned mean noses, eyes, ears and hands .

- ↑ The Katharevousa was very similar to ancient Greek in some grammatical areas and, for example, had more cases and significantly more participles than the modern Greek vernacular. The greater variety of forms and the more complex syntax - in some cases not unlike the Latin or German language - allowed the technically accurate naming of complicated facts, whereas lyrical expressiveness and emotional richness were lacking, since the Katharevousa did not arise from the “people's soul”, but artificially constructed and constructed thus was in a sense lifeless.

- ↑ Karvounis (2002), p. 15