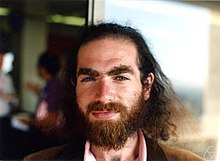

Grigori Jakowlewitsch Perelman

Grigori Perelman ( Russian Григорий Яковлевич Перельман , scientific transliteration Grigory Jakovlevic Perel'man * 13. June 1966 in Leningrad , Soviet Union ) is a Russian mathematician and expert in the mathematical areas of topology and differential geometry , in particular in the field of Ricci flow .

In 2002 he published his proof of the Poincaré conjecture . This is one of the Millennium Problems published in 2000 , the solution of which is considered particularly important. It is the only solved Millennium Problem so far.

Life

Perelman is of Jewish origin, his father was an electrical engineer, his mother a math teacher. His mathematical training began in the fall of 1976 at the Mathematical Club in the Leningrad Pioneer Palace . At the age of 14 he attended Mathematical Technical School number 239 in Leningrad. In 1982 he won a gold medal as a student at the International Mathematical Olympiad (with a perfect score) and was therefore admitted to the course without an entrance examination. For example, he was not affected by the discrimination against Jewish study candidates in the grading of the entrance tests, which were also held at the end of the Brezhnev period and during the Andropov period. After graduating, he worked at the Steklow Institute for Mathematics in Leningrad with Yuri Dmitrijewitsch Burago . Perelman received his PhD around 1990 from the Faculty of Mathematics and Mechanics at Leningrad University on saddle surfaces in Euclidean spaces . His doctoral supervisor was Burago; However, as he foresaw difficulties due to Perelman's Jewish origins - in the 1970s and 1980s there were still restrictions on admission to doctoral studies, especially at the Steklow Institute - academician Alexander Danilowitsch Alexandrov was put forward as the official supervisor.

As a post-doctoral student , Perelman was sponsored by Michail Gromow from the Institute des Hautes Études Scientifiques and invited there. In 1992 he was in the USA at the State University of New York at Stony Brook and at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences of New York University with Jeff Cheeger . In 1993/94 he was a Miller Research Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley and then returned to the Steklow Institute in St. Petersburg in 1995, despite offers from Princeton University and Stanford University . According to Ludwig Faddejew , since his abilities were known, he was allowed to work there largely undisturbed, although he hardly published and refused to defend his habilitation (called a doctorate in Russia). As the only leading scientist at the institute, he had only one candidate status. Until the fall of 2002, Perelman was mainly known for his work in differential geometry . However, he had fallen out with his former boss Burago and joined the department of Olga Ladyschenskaya and her successor Seregin. In 2005 there was a conflict with the administration of the Steklow Institute, which developed over the fact that unspent research funds were paid out to the employees, with which Perelman did not agree. In December 2005 he left the Steklov Institute, informing the director Sergei Kislyakov that he was disappointed with the math and wanted to try something different.

He turned down the EMS Prize of the European Mathematical Society , which he was awarded in 1996, as well as the Fields Medal of the International Mathematical Union , which he was awarded in 2006. He also turned down the one million dollar prize money from the Clay Mathematics Institute , which he was awarded in 2010.

After doing research in a friend's dacha in complete isolation for a while, Perelman now lives again with his mother on the outskirts of St. Petersburg. Since he quit his position at the Steklow Institute in 2005, Perelman has been without a permanent position. In 2011 he was proposed by Faddeev with the support of the Steklov Institute for admission to the Russian Academy of Sciences .

Perelman plays the violin and is an avid table tennis player. His younger sister Elena Perelman is also a mathematician. She received her PhD at the Weizmann Institute and works as a biostatistician at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm .

plant

Perelman drew attention to himself even before his work on the Poincaré conjecture by working on differential geometry. This work also earned him the prize for young mathematicians of the European Mathematical Society (EMS Prize) in 1996.

Perelman developed the theory of Alexandrov spaces (with curvature limited downwards) including a structure theory and a stability theorem. Alexandrov spaces are named after his teacher AD Alexandrov and are more flexible than Riemannian manifolds . With his teacher Burago and Michail Leonidowitsch Gromow he published a review article on these rooms.

In 1994 he published a new short and elegant proof of the Soul set (ger .: Soul theorem), the first of Jeff Cheeger and Detlef Gromoll had been proved 1,972th In 1994 he was a speaker at the International Congress of Mathematicians (ICM) in Zurich ( Spaces with curvature bounded below ).

The Poincaré Conjecture and Fields Medal

In November 2002, published Perelman on the document server preprint arXiv the first article of a series, the intended, the geometrization of William Thurston to prove. In this proof, the Poincaré conjecture is included as a special case. Perelman also emailed the proof to well-known mathematicians. During his time in the USA, he had already learned about the possibility of proving the geometrization conjecture and the Poincaré conjecture via the theory of the Ricci flows by Richard S. Hamilton from the early 1980s. Hamilton himself worked on it and had contact with Perelman in the USA. After his return to Russia, Perelman worked in relative isolation on the evidence for seven years and, in his own words, also offered Hamilton a cooperation during this time, which he did not answer. In April 2003, Perelman lectured on his work at Princeton, Stony Brook, and Columbia University (where Hamilton was among the audience). After that, he left it to others to check and did not participate.

Perelman's work was reviewed for a long time (2003–2006) by the mathematical experts. In the meantime, three teams of experts have checked the evidence ( Tian Gang and John Morgan , Cao Huaidong and Zhu Xiping , Bruce Kleiner and John Lott ) and, after intensively examining the evidence, have expressed their opinion that it is correct. Richard Hamilton also checked the correctness independently together with Tom Ilmanen and Gerhard Huisken . Perelman's proof contained a few inaccuracies and small errors, but these could be corrected as part of the verification of the proof and did not represent any major problems.

Perelman received the Fields Medal for the proof in 2006 , which is generally much more than just the official recognition of the proof: the medal is equivalent to a Nobel Prize in mathematics . Perelman rejected the medal, as did the EMS Prize . This made him the first recipient of the highest mathematics award to refuse receipt. So far, something comparable has only happened with Alexander Grothendieck , who was awarded the Fields Medal in 1966. In contrast to Perelman, Grothendieck accepted the award, although for political reasons he refused to travel to Moscow for the official award ceremony. Before the award ceremony, even the President of the International Mathematical Union (IMU), the British John M. Ball , tried in vain in St. Petersburg to persuade Perelman to accept the award.

Soon after his rejection of the Fields Medal, he gave an interview for the first time in June 2006, in which he went into detail about the prehistory and complained that other mathematicians were wrongly claiming shares in the proof of the Poincaré conjecture. He was referring to the first complete publication of the evidence by Cao and Zhu, two protégés of Shing-Tung Yau , who presented it at the string theory conference in Beijing in June 2006 and the preliminary work by Richard Hamilton, with Yau himself for many years on Ricci -Rivers worked together, highlighting the incompleteness of Perelman's publications. Cao and Zhu's publication also made a similar impression in its title. The interview with Perelman was part of an article by Sylvia Nasar (bestselling author of a book on John Nash ) and David Gruber Manifold Destiny in The New Yorker on August 28, 2006. In it, Perelman announced his retirement from mathematics. Yau later found himself unfairly portrayed in the article and denied having questioned Perelman's priority, with the support of Hamilton.

As early as 2000, the Clay Mathematics Institute had counted the Poincaré conjecture among the seven most important unsolved mathematical problems and offered a price of one million US dollars for the solution (provided it was published in a specialist journal). Perelman, who published his work on the Internet, has so far shown no interest in publishing his proof in a professional journal, nor in claiming the prize for himself. The Clay Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, which also funded the verification of the evidence by Tian and Morgan as well as another team, nevertheless awarded Perelman the prize money for the first solution to one of the seven millennium problems after extensive tests on March 18, 2010 to. However, this refused the award again. He justified this decision with his dissatisfaction with the organization of the mathematical society, since he did not like its decisions. He thinks it is unjust.

literature

- Graham P. Collins: The Shapes of Space . In: Scientific American . New York NY 2004, 7 (July), pp. 94-103. ISSN 0036-8733

-

Masha Gessen : Perfect rigor: A Genius and the Mathematical Breakthrough of the Century , Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2009

- German translation: The proof of the century: The fascinating story of the mathematician Grigori Perelman , Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2013, ISBN 978-3-518-42370-7

Fonts

- with Petrunin: Extremal subsets in Aleksandrov spaces and the generalized Liberman theorem, Algebra i Analiz, Volume 5, 1993, pp. 242-256

- Elements of Morse theory on Aleksandrov spaces, Algebra i Analiz, Volume 5, 1993, pp. 232-241

- Spaces with curvature bounded below, Proc. ICM, Zurich 1994

- Elements of Morse theory on Alexandrov spaces. In: St. Petersburg Mathematical Journal. Volume 5, 1994, p. 205

- with Y. Burago, M. Gromov: Alexandrov spaces with curvature bounded from below. In: Uspekhi Math. Nauka. Volume 47, 1992, pp. 3-51, and Russian Mathematical Surveys, Volume 47, 1992, No. 2, pp. 1-58

- Proof of the soul conjecture of Cheeger and Gromoll. In: Journal Differential Geometry. Volume 40, 1994, pp. 209-212

- The entropy formula for the Ricci flow and its geometric applications, Arxiv 2002

- Ricci flow with surgery on three manifolds, Arxiv 2003

- Finite extinction time for the solutions to the Ricci flow on certain three manifolds, Arxiv 2003

Web links

- George Szpiro: Ingenious hermit. In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . July 23, 2006, accessed November 5, 2013 .

- Ulrich Schnabel: The missing genius. In: The time . August 24, 2006, accessed November 5, 2013 .

- Peter Schiering: Modest genius. In: Kulturzeit . August 24, 2006, accessed November 5, 2013 .

- RIA Novosti : Grigory Perelman, a Jewish genius of Russian mathematics , August 25, 2006

- image of science : The Spirit of St. Petersburg , 5/2008

- SWR2 Knowledge: The Perelman Conjecture for Listening (26 Min.) And Reading, March 31, 2008

- Der Spiegel : The Millennium Problem Solved - Mathematicians uncertain whether the bonus will be accepted , March 22, 2010

- brand eins: Grigori Perelman and the attempt to get closer. “He just wants to calculate” , 11/2011

- Geo audio report about Perelman: "The genius of the century" , January 8, 2012 (print version GEO 01 | 2012 p. 50)

English web links:

- Petersburg Department of Steklov Institute of Mathematics (English, Russian), November 9, 2001

- Notes and commentary on Perelman's Ricci flow papers (English)

- Perelman's papers published on arXiv.org (English)

- New Yorker: Manifold Destiny: Who really solved the Poincaré conjecture? (English), August 28, 2006

- Telegraph: World's top maths genius jobless and living with mother (English), August 20, 2006

- Entry at mathnet.ru (more detailed the linked Russian version)

- Literature by and about Grigori Jakowlewitsch Perelman in the bibliographic database WorldCat

Individual evidence

- ^ Biography of Perelman, English

- ↑ Masha Gessen: The Proof of the Century: The Fascinating Story of Mathematician Grigori Perelman . Chapter 3, Suhrkamp, ISBN 978-3-518-42370-7 .

- ↑ Deutschlandfunk: The White Raven of May 11, 2008

- ↑ Masha Gessen Perfect Rigor , Chapter 6

- ↑ Gessen, loc. cit.

- ↑ Ludwig Faddejew in an interview in 2007 in Russian

- ↑ Masha Gessen: Perfect Rigor . Chapter 10

- ↑ Grigori Perelman to become academician against his will , Pravda, September 15, 2011

- ↑ Laudation for the EMS Prize, Notices AMS 1997, PDF file

- ↑ Perelman: Alexandrov's spaces with curvature bounded below II , Preprint, University of California 1991 (not published); Spaces with curvature bounded below , Proc. ICM, Zurich 1994; Elements of Morse theory on Alexandrov spaces. In: St. Petersburg Mathematical Journal. Volume 5, 1994, p. 205

- ↑ They are defined as complete linear spaces with curvature limited downwards and finite (Hausdorff) dimensions . Longitude means that the distance between two points is given by the infimum of the lengths of the curves that connect these points.

- ↑ Perelman, Y. Burago, M. Gromov: Alexandrov spaces with curvature bounded from below. In: Uspekhi Math. Nauka. Volume 47, 1992, pp. 3-51, and Russian Mathematical Surveys, respectively

- ^ Perelman: Proof of the soul conjecture of Cheeger and Gromoll. In: Journal Differential Geometry. Volume 40, 1994, pp. 209-212

- ^ Sylvia Nasar, David Gruber: Manifold Destiny . In: The New Yorker . August 28, 2006

- ↑ Einsiedler disdains math medal on Spiegel-Online from August 22, 2006. Retrieved on June 17, 2009

- ^ A Complete Proof of the Poincaré and Geometrization Conjectures - application of the Hamilton-Perelman theory of the Ricci flow

- ^ Nasar, Gruber Manifold Destiny, The New Yorker, August 28, 2006

- ↑ Yau website with related documents

- ^ Dennis Overbye The emperor of Math , New York Times, October 17, 2006

- ↑ George Szpiro: Ingenious Hermit. (No longer available online.) In: Neue Zürcher Zeitung . July 23, 2006, archived from the original on September 17, 2008 ; Retrieved November 5, 2013 .

- ↑ Handelsblatt: Award rejected: math genius waives a million dollars , July 1, 2010

- ^ Clay Mathematics Institute on Perelman's solution of the Poincaré conjecture and literature on it.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Perelman, Grigory Jakowlewitsch |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Перельман, Григорий Яковлевич; Perel'man, Grigorij Jakovlevič (scientific transliteration) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian mathematician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 13, 1966 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Leningrad |