Uroscopy

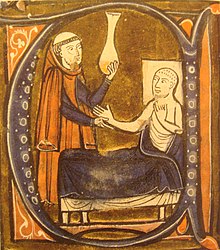

The uroscopy or urine inspection is the examination and testing of urine for diagnostic purposes ( Urognostik ). From antiquity until well into the early modern period, it was the most important diagnostic tool in medicine in the field of humoral pathology , the theory of humors according to Hippocrates of Kos (approx. 460 to approx. 370 BC) and Galen of Pergamon (approx. 129 BC) until approx. 216 AD).

history

Uroscopy, which has already been reported in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt , has its ancient roots primarily in the observations of the Hippocrats and was further elaborated by Galen, among others, whose influence on medical thought extended well into the 16th century. The Byzantine doctors Oreibasios , Aëtios von Amida and Alexander von Tralleis also dealt with uroscopic teachings in their writings from the 4th to the 7th centuries. According to the doctrine of juices, the condition of human urine could be used to demonstrate or exclude any illnesses in the person concerned due to the underlying defective mixture of body fluids. From around 1500, the urine inspection also served to identify a weakened or excessive heat of life ( calor vitalis ) or pathologically altered substances that the body tried to excrete through the urine.

Correspondences with modern medical diagnosis or medical semiotics can sometimes be found, for example in the Corpus Hippocraticum : "If fat floats like cobweb in the urine, it means that the person is consumptive" or "If the urine stinks, even closed If the patient is thin or too thick and black in color, the patient can gradually prepare himself for his last journey ”.

Isaak ben Salomon Israeli (Isaak Judäus) wrote a book about the urine (Arabic Kitāb al-baul, Latin Liber de urinis) in the 10th century, in which extensive, admittedly not in the sense of modern medical knowledge and broad or speculating about the Hippocratic and Going beyond the fundamentals further developed by Galen, the essence of urine as well as its different colors, substances and sediments and their diagnostic interpretations are discussed. Similar uroscopic content can also be found in the work Canon medicinae of the Persian doctor Avicenna , who served as an author ("Avicenna speaks: ...") for writers of urinary examination texts until the 16th century.

The Byzantine Christian court doctor Theophilos Protospatharios (7th century), whose urination theory Peri urōn , which was created around 670 by Constantine in the 11th century, was imparted to the West by Constantine in the 11th century, and the Byzantine doctor and were among the most important representatives and founders of the theory of urinary tracts practiced in the Middle Ages Author of a seven-volume medical textbook Aktuarios from around 1300 (* around 1275; † after 1328).

In the Middle Ages, for example, the preacher Berthold von Regensburg , who spoke publicly of the art of the "high masters", of being able to recognize "nature and sinen sinen siechtuom by a glass of man", pointed out the importance of the Harnschau .

The were from the urine inspection resulting therapeutic consequences, for example in the work Maurus of Salerno ( Regulae urinarum , one resulting in the 12th century on the Gulf of Naples Harnlehre ) up and look, as well as the also from the School of Salerno originating physician Walter of Agilon, who in the 13th century in his Summa medicinalis structured all medicine according to the criteria of uroscopy.

The Carmina de urinarum judiciis by Aegidius von Corbeil , written at the beginning of the 13th century, was also considered to be an important urinary textbook until the 17th century .

The painter and Rembrandt student Dou made some genre pictures with urination scenes in which the uroscopy is used by a urine examiner for "dropsy", "bleaching" and "lovesickness", among other things.

After already in the 17th century, when William Harvey's discovery of the circulatory system could refute the galenic notion of blood movement, urine diagnostics from a more modern scientific point of view was considered by the anatomist Laurentius Bellinus (1643-1704), in the 18th century uroscopy is increasingly enriched by the application of chemical detection methods. In 1736 the Halle clinician J. Juncker coined the term “urology” for the art of “... looking at the water”. 61 years later, the Scottish chemist and anatomist William Cumberland Cruikshank (* 1745 in Edinburgh , † 1800 in London ) first described protein in the urine ( albuminuria ) as a sign of liver disease .

At the beginning of the 19th century, the scientific analysis of urine began to replace the medieval urine examination.

execution

In classical urine inspection of the morning urine ( "cockcrow") according to a sophisticated technique in a transparent glass vessel (which was Matula said urine glass ) collected. The matula with the urine sample was protected from light and cold or heat in a basket (often made of bast urinal baskets or urinary glass quivers) brought to the urine shower, which then received the urine in detail and sometimes twice - first "fresh" and then again or two hours - peer-reviewed. The urine was tested for consistency, color and additions, sometimes also for taste and smell. 20 different urine colors (from crystal clear to light yellow, camel hair beige, wine red, liver colored and deep green to black) were mostly distinguished (described in the Fasciculus Medicinae by an unknown author from 1491 and in Epiphaniae medicorum. Speculum videndi urinas hominum by Ulrich Pinder from 1506). So-called urine glass disks (or urine charts or urine charts) were used as aids. The consistency was divided into thin , medium or thick . Furthermore, the urine was examined for admixtures ( Latin : contenta = ingredients), which included the formation of bubbles, fat droplets and sand, leaf, bran-like and lenticular, differently colored precipitates, cloudy precipitates and other concrements. Only since the 17th century was associated a sweet taste of the urine with the presence of diabetes mellitus, the sugar disease .

The following humoral-pathological classifications existed in medieval and early modern urination:

- Red and thick urine: signs of a person of heated nature (sanguine)

- Red and thin urine: signs of a person of a hot and dry (dry) nature (choleric)

- White and thick urine: signs of a person of cold nature (phlegmatic)

- White and thin urine: signs of a person of cold nature (melancholic)

The formation of different layers in the urinary glass was also interpreted according to the anatomy:

- The "circle" ( vicious as the top liquid rim) head diseases in question in terms of especially the brain and sensory organs

- The part after the circle, the upper urinary layer ( superficies ) meant disease of the chest or the thorax, or of the heart and arteries, and the lungs

- The middle part in the abdomen (urinary glass middle) should indicate diseases of the stomach, liver or spleen as well as other nutritional organs

- The sediment at the bottom of the piston (bottom of the vessel) in relation to the kidneys, urinary bladder and uterus as well as genital organs.

The correspondence between urine and the human body with the representation in the urinary glass, already assumed by actuaries, who increased the number of urinary glass layers from four to eleven and even related the inclination of the urinary sediment surface to the right or left side of the body, continued until the 16th Century increasingly, culminating in the work Confirmatio of Leonhard Thurneysser von Thurn , more speculative manifestations.

Good gushers (doctors) were supposedly able to tell male and female urine apart and even determine pregnancies and the sex of the unborn child. Around 950, for example, St. Gallen monks told Duke Heinrich I of Bavaria , a brother of Otto the Great , that he would be born in a month. The Duke was very pleased with this news, since he had sent the urine of a heavily pregnant maid instead of his to test the medical knowledge of the monks in St. Gallen. The Wroclaw Pharmacopoeia (Codex Rhedigeranus 291), which was created around 1270 to 1310, also shows such fertility and pregnancy tests.

In Jost Amman's book of status from 1568, the profession “The Doctor” is depicted with a urine glass in his hand, who can only recognize the disease and prescribe the correct medicine by looking at the urine. It is described as follows with verses by Hans Sachs :

"I am a Doctor of Artzney /

On the urine I can see freely /

What sickness a person does load /

That I can help with God's grace /

With a syrup or

recipe /

That resists his illness / That the person becomes healthy again /

Arabo the Artzney invented. "

The state of urine was assessed taking into account the physical condition, temperament and gender of the test person and the time of year. Even then, as now, the urinary and clinical findings of the patient were assessed in connection. In addition to pulse diagnostics (which was, however, much less respected until modern times), urination developed into a diagnostic method for most known diseases. In elaborate theories, the learned doctors tried to explain the different urinary changes with the help of the pathophysiological theories of the time. Watery, thin urine, for example, indicated a weak, possibly mucous stomach or a weakened digestive warmth.

Because of the “infallible diagnostic method” for almost all diseases by medieval doctors (and also in the 18th century and beyond), which was regarded as an essential medical activity, the flask-shaped urinary glass, the matula, was raised at that time. the symbol of the medical profession. It can still be found today in the emblems of several professional urological associations such as the “Professional Association of German Urologists”, the “German Society for Urology” (DGU) and the “American Urological Association” (AUA).

In naturopathic practice, a modified classic urine examination is still a key diagnostic method today. In the clinic and in the medical practice nowadays, as part of a urine test, in addition to chemical laboratory tests, the urine is routinely examined for color, odor and impurities. The results of this examination contribute to the diagnosis . In the 20th century , light microscopic examinations were developed that can provide further information on certain diseases.

criticism

Already in ancient times the representatives of the Harnschau were attacked by the followers of Erasistratos and called uropotas , among other things . Around 1300 Aktuarios, who was described as the founder of the actual Harnschau, had strongly criticized the ancient uroscopic teachings of Hippocrates and Theophilos. After Agrippa von Nettesheim attacked the uroscopy methods of his time in the 16th century (for example the "urine tasting"), the improper and "correct" use of urine was differentiated and after the Dutch doctor Pieter van Foreest (with his writing De incerto, fallaci urinarum iudicio, que uromantes ad perniciem multorum aegrotantium utuntur et qualia illi sint observanda, tum praestanda, qui recte de urinis sit iudicaturus of 1589) the charlatanism in dealing with urination (as uromancy ) has been portrayed since 20th century often associated with superstition or popular belief, but at the time of its widespread use, most doctors regarded it as a proven diagnostic method and the basis of medical authority. Criticism was only directed against the widespread practice of diagnosing diseases of all kinds exclusively from the urine, without even seeing the patient himself. Personal physicians at royal courts were also encouraged to use uroscopy in diagnosis. For example, Adam Reuter, the personal physician of the Bamberg prince-bishop Veit II. Von Würtzburg , was even sworn to examine the ruler's pulse and “their grace fountain” (the urine) of the ruler without being asked.

One of the last known “urine showers” was the Styrian natural healer Johann Reinbacher vulgo Höllerhansl (1866–1935), who “treated” his “patients” (even in absentia) by examining the urine without any medical training. He was popular with the people and was sued by the medical profession.

The ancient Greeks, Egyptians, Persians, Indians and Chinese already knew about the possible sweetness of urine, but it was not until 1675 that Thomas Willis (1621–1675) introduced the additional name mellitus and it was not until 1776 that the British doctor and natural philosopher Matthew Dobson ( 1732–1784) a type of sugar in the urine is responsible for its sweet taste. Johann Peter Frank (1745-1821) is credited with being the first to distinguish between diabetes mellitus and diabetes insipidus in 1794 .

See also

literature

- Johanna Berger : The development of urine diagnostics from urine examination to urine examination. Medical dissertation, Münster 1965.

- Johanna Berger: From Uroscopy to Urochemistry. In: Hippocrates. Volume 37, (Stuttgart) 1966, pp. 653-657.

- Johanna Bleker : The art of seeing urine - an 'elegant and necessary limb of the beautiful Artzney'. In: Hippokrates 41, 1970, pp. 385-395.

- Dieter Breuers: knight, monk and farmer. An entertaining story of the Middle Ages . Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1997, ISBN 3-404-12624-6 .

- Hans Christoffel : Fundamentals of uroscopy . In: Gesnerus . Vol. 10, No. 3-4, 1953, pp. 89-122.

- Kay P. Jankrift: With God and black magic. Medicine in the Middle Ages . Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8062-1950-8 .

- Gundolf Keil : The urognostic practice in pre- and early Salernitan times , medical habilitation thesis, Freiburg im Breisgau 1970 (typewritten copy in the Institute for the History of Medicine in Würzburg).

- Gundolf Keil: Theory and Practice of Salernitan and Late Medieval Uroscopy. Ref. 65th Annual Meeting of the German Society for the History of Medicine, Science and Technology e. V., Trier 1982.

- Gundolf Keil: Urn writings. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil, Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 533-535.

- Johannes Gottfried Mayer : ›Twelve pieces of the harne‹. A uroscopy from the urine of the ›Alsatian Pharmacopoeia‹. In: Konrad Goehl , Johannes Gottfried Mayer (Hrsg.): Editions and studies on Latin and German specialist prose of the Middle Ages. Festival ceremony for Gundolf Keil. Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg 2000. ISBN 3-8260-1851-6 , pp. 193-205.

- Julius Neumann: History of Uroscopy. In: Journal of Medicine. Volume 15, (Berlin) 1894, pp. 53-77.

- Hans-Dieter Nöske: Uroscopia. Basic features and development of urine diagnostics. (Inaugural lecture at the Medical Faculty of the University of Gießen) In: Materia medica Nordmark (Hamburg). Volume 31, 1979, No. 11-12, pp 340-353.

- Thomas Schlich. The urine glass as a distinguishing feature of the learned doctor. Urine diagnostics and medical status in the Middle Ages , Spectrum of Nephrology , 5, 1992, 5-9.

- Michael Stolberg : The Harnschau. A cultural and everyday story. Böhlau-Verlag, Cologne / Weimar 2009, ISBN 3-412-20318-1 .

- Karl Sudhoff : The urinary glass pane in the 15th century. In: Tradition and observation of nature in the illustrations of medical manuscripts and early prints (= Studies on the History of Medicine, I. ) Leipzig 1907, pp. 13-18.

- Hans J. Vermeer : A "Iudicium urinarum" by Dr. Augustin Streicher from Cod. Wellc. 589. In: Sudhoff's archive. Vol. 54, 1970, pp. 1-19.

- Faith Wallis: Inventing Diagnosis: Theophilus' “De urinis” in the classroom. In: DYNAMIS . Acta Hisp. Med. Sci. Hist. Illus. 2000, 20, 31-73.

- Walter Wüthrich: The Harnschau and its disappearance. (Medical dissertation Zurich 1967) Zurich 1967 (= Zürcher Medizingeschichtliche Abhandlungen , 42).

- Friedrich v. Zglinicki : Uroscopy in the fine arts. An art and medical historical study of the urine examination. Ernst Giebeler, Darmstadt 1982, ISBN 3-921956-24-2 .

- Adolf Ziegler: Uroscopy at the bedside. Erlangen 1861 and 1865.

Web links

- Lecture "Harnschau 2015, Harnschau and back pain. Friedrich Koller"

- Lecture "The traditional urination has been practiced and passed on in my family for over 200 years"

- Emblem of the DGU

- Doctor with matula

- Medieval Harnschau

- Harnschau & stone carving

- Diagnostics in the Middle Ages

- Harnschau in naturopathic practice

- Provincial Museum of Lower Austria

Individual evidence

- ^ Wilhelm Held: The urine show of the Middle Ages and the urine examination of the present. Leipzig 1931.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki: Uroscopy in the fine arts. An art and medical historical study of the urine examination. 1982, p. 5.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki: Uroscopy in the fine arts. An art and medical historical study of the urine examination. 1982, p. 5.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki: Uroscopy in the fine arts. An art and medical historical study of the urine examination. 1982, p. 8.

- ↑ Johannes Actuarius: De urinis libri septem. Edited by Ambrosio Leone Nolano. Basel 1529.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki: Uroscopy in the fine arts. An art and medical historical study of the urine examination. 1982, p. 6.

- ^ Hans-Dieter Nöske: Uroscopia. 1979, p. 346.

- ^ Franz Pfeiffer : Berhold von Regensburg, sermons. Volume 2, Vienna 1862, p. 153.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki: Uroscopy in the fine arts. An art and medical historical study of the urine examination. 1982, p. 7.

- ↑ Paul Diepgen : Gualtari Agilonis Summa medicinalis. According to the Munich Cod. La. Nos. 325 and 13124 edited for the first time with a comparative consideration of older medical compendia from the Middle Ages. Leipzig 1911.

- ↑ Wolfgang Wegner: Gualtherus Agulinus (Gualterius, Galterus, Valtherus, surnames: Agilon, Agilus, Agulum). In Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 514.

- ^ Hans-Dieter Nöske: Uroscopia. 1979, p. 349.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki: Uroscopy in the fine arts. An art and medical historical study of the urine examination. 1982, pp. 5 f., 12, 14, 23 and 26 f.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), pp. 98, 107-111 and 113.

- ↑ Erich Ebstein : On the development of clinical urine diagnostics. In: Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. Volume 26, No. 46, 1913, pp. 1900-1902.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), p. 152.

- ↑ Laurentius Bellinus: De urinis quantum ad artem medicam pertinent. 1683.

- ↑ Joseph Loew: About the urine as a diagnostic and prognostic sign. Landshut 1808.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), pp. 11 and 19.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), pp. 25-27 and 54-59.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), p. 8 f.

- ↑ E. Pergens-Maeseyck: A urine display board from Cod. Brux. No. 5876 with comment. In: Sudhoff's archive for the history of medicine. Volume 1, No. 6, 1908, pp. 393-402 and Plate IX.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), pp. 7-9.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), pp. 23 and 25.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), pp. 12 and 147 f.

- ^ Johanna Bleker: The urine diagnostics of Leonhard Thurneysser to Thurn. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt , Volume 67, No. 43, 1970, pp. 3202-3209.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), pp. 12-14 and 148.

- ↑ Gundolf Keil: 'Breslau Pharmacopoeia'. In: Werner E. Gerabek et al. (Ed.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 209.

- ↑ Gundolf Keil: 'Breslau Pharmacopoeia'. In: Burghart Wachinger et al. (Hrsg.): The German literature of the Middle Ages. Author Lexicon . 2nd, completely revised edition, volume 1: 'A solis ortus cardine' - Colmar Dominican chronicler. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1978, ISBN 3-11-007264-5 , Sp. 1023 f.

- ↑ Carl Külz, E. Külz-Trosse, Jos. Klapper (Ed.): The Breslau Pharmacopoeia. R [hedigeranus] 291 of the city library, part I: text. Dresden 1908 (Codex today in the University Library of Breslau) - digitized .

- ↑ Ruth Spranger: The Latin prescriptions in the 'Breslauer Pharmacopoeia' (Cod. Rhed. 29 of the University Library of Breslau): Observations on the source question with the East Central German 'Bartholomäus'. In: Gundolf Keil (Ed.): Würzburger Fachprose-Studien. Contributions to medieval medicine, pharmacy and class history from the Würzburg Medical History Institute. Festschrift Michael Holler. Würzburg 1995 (= Würzburg medical historical research. Volume 38), pp. 98–117.

- ↑ Horst Kremling: On the development of kidney diagnostics. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 8, 1990, pp. 27-32m here: p. 27.

- ^ Gerhard Baader , Gundolf Keil: Medieval diagnostics. In: Medical diagnostics in the past and present. Festschrift for Heinz Goerke on his sixtieth birthday. Edited by Christa Habrich , Frank Marguth and Jörn Henning Wolf with the assistance of Renate Wittern . Munich 1978 (= New Munich Contributions to the History of Medicine and Natural Sciences: Medizinhistorische Reihe , 7/8), pp. 121–144.

- ↑ Christoph von Hellwig : Valentini Kräutermanns Curieuser and reasonable urine doctor, who teaches and shows in part how one not only thoroughly recognizes most and most distinguished diseases of the human body from the urine according to certain art rules of medicine, but also how a reasonable judgment must be made of it. On the other hand: How one should also see from the pulse the condition of the blood, the strength and weakness of the spirits of life, the decrease and increase in disease . Niedt, Frankfurt am Main 1724.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), p. 13 f.

- ↑ Davach de la Rivière: Le miroir des urines. Paris 1700; first German edition: Urin-Spiegel, in which, according to experience, the famous - both old and new Medicorum - the various types of nature: penetrating blood humidity of the blood; and to see the origin of their diseases in every human being. Published in French [...]. Well, translated [...] into German. Including an addition of the most common diseases, and the most peculiar means for [...] special aid to the poor in the country (by JA Helvetius). 2 in 1 vol., Gastel, Stadtamhof 1744.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), p. 6 f.

- ↑ Urine Doctor. The wolerfahrne of the instructions for recognizing all diseases from the urine [...]. Friedrich Ebner, Ulm 1851; Reprint Freiburg im Breisgau 1978.

- ↑ Julius Neumann: History of Uroscopy. In: Journal of Medicine. Volume 15, (Berlin) 1894, pp. 53-77.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), p. 147.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), p. 6.

- ↑ Sigmund Kolreutter: On the right and useful in artzney use of the urine and water inspection and against it some abusive [...]. Nuremberg 1524.

- ↑ Bernhardus Rappard: De uromantiae et uroscopiae abusu tollendo. Dissertation Magdeburg 1711.

- ↑ Johann Rudolph Staegerus: De usu et uromantias abuso. Basel 1702.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), pp. 147-152.

- ↑ M. Weiss: The Harnschau in popular belief and in science. In: Wiener Medizinischer Wochenschrift. No. 1, 1935, pp. 505-507, and No. 19, 1935, pp. 529-535.

- ^ Karl Ludwig Sailer: Health care in old Bamberg. Dissertation, Erlangen 1970, p. 51.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki (1982), p. 7.

- ↑ pharmacareers: Diabetes - History, part 1 ( Memento of the original from October 7, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ M. Dobson: Nature of the urine in diabetes . In: Medical Observations and Inquiries . 5, 1776, pp. 298-310.

- ↑ Heinz Schott among others: The Chronicle of Medicine . Chronik-Verlag, 1993, ISBN 3-611-00273-9 .