Hecla-Grindstone Provincial Park

|

Hecla-Grindstone Provincial Park

|

||

|

Grassy Narrows Marsh |

||

| location | Manitoba (Canada) | |

| surface | 1084 km² | |

| WDPA ID | 4171 | |

| Geographical location | 51 ° 17 ′ N , 96 ° 43 ′ W | |

|

|

||

| Setup date | 1969 | |

| administration | Manitoba parks | |

The Hecla-Grindstone Provincial Park is a 1969 established provincial park in Lake Winnipeg in the Canadian province of Manitoba . It is located 190 km north of Winnipeg , the capital of the province, and serves to preserve and research the fauna and flora that exist there, as well as the cultural relics of the First Nations there and the Icelandic community that lived there until a few decades ago . The limestone cliffs in the park area are also to be protected. For these reasons, the park was rededicated from a nature park to a so-called heritage park in 1988 , as not only the natural but also the cultural heritage is to be protected here.

The approximately 1084 km² large park includes the 163.8 km² Hecla Island, then the Deer Island north of Hecla, plus Punk and Little Punk Island and Goose Island, and finally Black Island, the second large island in the park area. The park also includes Grindstone, a long peninsula similar in size to Hecla that extends on the west bank of Lake Winnipeg. It was added to the park founded in 1969 in 1997. The park also includes the water surface between the west and east shores of the lake in the area of the islands. Economic-industrial use (development) is only permitted around Gull Harbor in the northeast of the island.

Apart from the Grindstone Peninsula and the town of Hecla, the park is largely uninhabited. The oldest pottery in the province was found on the island, dating from around the time of the birth of Christ. The Indian population of the Saulteaux , who lived there until 1875 and was known as the Iceland band , had to leave Hecla under pressure from the Canadian government. Most of their offspring live in a reserve called Wanipigow on the eastern shore of the lake. The up to 500 Icelanders who lived on Hecla from 1876, in a district where only Icelanders were allowed to live until 1897, left the island from the 1960s. In addition to its historical heritage, the provincial park also harbors large colonies of birds, among which the rhinoceros pelicans are of particular importance.

Geology and climate

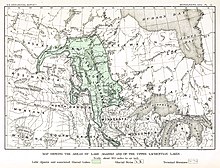

The island of Hecla is located in the approximately 24,500 km² large Winnipeg Lake, which extends over a length of 416 km north-south. The “Narrows”, bottlenecks north of Hecla, divide the lake into two halves, with the north having a west-east extension of 100 km, the south of only 40 km. The narrowest point, however, is near Hecla, east of Black Island, where the lake is only 500 m wide, but also has the greatest depth there at around 60 m. Overall, Lake Winnipeg is relatively flat.

Hecla originated around 450 million years ago. Tropical lakes deposited clay and sand there. These were compacted into sandstone and slate . The lake became deeper and thick layers of limestone were deposited. In some areas there are also granites and in some places volcanic remains are exposed. However, limestone and glacial deposits are predominant on the surface . The higher-lying areas consist of calcareous moraines and tillites that were deposited in the last ice ages. Their thickness varies between 53 and 150 m. The base rock consists of limestone and dolomite . There are a number of limestone cliffs in the park.

When the glaciers began to melt towards the end of the last Ice Age, Lake Agassiz was formed around 11,700 years ago and covered a large part of Manitoba. It left a thin layer of organic material, although Tillit continued to dominate. Deposited on loamy subsoil, these areas drain extremely poorly. The beaches around Hecla were created by eroded sandstone that the waves of the lake threw ashore. The waves, which are usually caused by sustained north winds in autumn, are of exceptional height when they reach Hecla. They lead to severe erosion and frequent flooding along the coasts, which is also related to the fact that when the winds decrease in a forward and backward process, the receding water masses intensify the erosion effects ( called seiching here ).

The region has been classified as humid continental. The frost period is shorter on the islands than on the surrounding mainland. Black Island has 110 frost-free days. Between 1961 and 1990, the average annual temperature at the closest measuring station, Arborg, west of the park, was 0.9 ° C, the average January temperature was −20.2 ° C, and the corresponding temperature in July was 18.4 ° C. 491 mm of precipitation fell, of which 22.4% was snow.

history

Early history up to the cession to Icelandic settlers

Hecla was home to the scattered Icelandic band , as the British and Canadian authorities later called them. Like most groups in the region, it may be traced back to immigration from the east that took place in the Laurel phase , around 2000 years ago. These immigrants belonged to the Ojibwa . They brought with them ceramics and new techniques, of which excavations at Wanipigow Lake (on the mainland east of the park) uncovered the oldest in the province. Numerous pottery shards date from around 700 to 1640. They could be assigned to different phases, especially Blackduck, Selkirk and Sandy Lake. In addition, places of ceremonies such as the medical society and burial sites can be found in the east of Black Island.

In 1734 a European first appeared in the region. Vérendrye reported that he had found iron ore, which may indicate the presence of hematite in what is now the park area. On a map from 1740 the island appears accordingly as Ile de Fer , as iron island . During this time, around 1733 to 1760, Cree probably lived here . The hematite was used as a color for body painting, but also for rock paintings, but not for iron extraction. These Cree left the area before 1800 and moved north and west, still maintaining some camps on the northern edge of the lake. In the 1790s, the Hudson's Bay Company established a trading post on the east end of Black Island.

From the south Ojibway groups came north, which the British referred to as "Red Lakers" and "Leech Lakers". This process dragged on for more than two decades, but by 1821 the group, later known as the Island band , was settled on Black Island and the neighboring islands. White fish, a larger herd of elk and large areas of blueberries provided an adequate food source. On the other hand, the Peguis Band was chasing Grindstone . They previously sat at Netley Creek, but avoided the Anglican missionary attempts. They also counted themselves among the Island bands and lived around Grindstone all year round. Their main camps were on the White Mud River and around Sandy Bar.

Like most of the tribes of Canada , they were to move to a reservation after 1871 to make way for white settlers. The so-called numbered treaties were concluded for this purpose. For the groups on Lake Winnipeg, this was primarily Contract No. 5 from September 1875. Behind it, however, were not only settlement interests, as pursued by the Canadian government, but also a group of investors from the ranks of the Methodist community , such as John Schultz or Donald Smith. They were mainly supported by Clifford Sifton and his brother-in-law Theo Burrows, the former from 1888 as a member of the Legislative Assembly of Manitoba , the provincial parliament. The entrepreneurial family of EJ Sanford from Hamilton , Ontario saw to it that missionaries were sent from 1868 onwards to make the Indians submissive on the islands, which were home to extensive forests. This was all the easier when Canada replaced the rule of private companies, above all the Hudson's Bay Company , and thus could make the logging independent of the American supply.

Henry McKenny was the first to cut trees on the islands in 1868. The legal pretext against the previous residents was that the Indians allegedly did not use the wood. But McKenny lost his permission to Donald Smith because of his pro-American stance. Since Canada was founded by Great Britain with the primary purpose of preventing the US from expanding northward, the government could not tolerate such men, especially when they called for Canada's annexation with the US.

Another danger loomed for the Methodists: the Cree around Norway House and Oxford House moved to other Cree around St. Peter's northwest of Hecla. This was most threatening to the Methodists in that the latter were Anglicans. So from 1874 a settlement was to be built on the Berens River (the wood of which came from Black Island) to intercept this southern migration. The Saulteaux resident there were not asked whether they wanted to pursue the ideal of industrial activity. The Methodists saw their activity in connection with the development of rail and ship connections in the region. In this speculation phase, numerous entrepreneurs and politicians made their fortunes. The basis was the exploitation of natural and mineral resources that the Indians stood in the way. In 1874, local iron was processed for the first time in the Vulcan Iron Works in Winnipeg, in the same year coal tar was found near Elk Island , as the Winnipeg Free Press reported on August 25, 1874. Logically, neither the Berens River Band nor the Island Bands were included in the first contracts. The hematite formations on Black Island were known by 1874 at the latest, although in 1943 it turned out that they were not worth exploiting because the thickness of the layer was less than 30 m. In 1874 the first fishing vessel appeared with the Venture .

The Iceland band demanded Hecla Island, which was part of their traditional territory, but the government officials refused. The reasons are not officially known, but they could be traced back to initiatives by the Methodist Mission and Investor Group. On September 20 and 24, 1875, the Indians on the Berens River and in Norway House (at the northern end of Lake Winnipeg) were persuaded to move to the Hollow Water River , and on 'Big Island', like them, the translation is followed , called, to forego. However, they believed their reservation would include at least Black Island, and on an 1882 map drawn up for Indian Reserves Surveys Canada , the island actually still appears as their territory. This is probably due to the fact that the annual meeting of their Midewiwin or Great Medical Society took place there.

For the Island bands , Ka-tuk-e-pin-ais or Hardisty put their mark on the contract, although the Canadian negotiators were clearly informed that the Island bands had no chief in common. He even demanded to be able to negotiate directly with the government, but the negotiators were able to prevent this.

Alexander Morris told the Methodists that the Indians dressed like "white men". Claims on the islands were made by the groups the Canadians called Bloodvein , Big Island and Sandy Bar . The latter was the Peguis group on the White Mud River and on the Big Island. The Big Island Band of this report from 1876 thus corresponded to the band on Black Island from 1875. They did not assign themselves to a specific area, but named themselves after their headman , usually a recognized hunter or shaman. It is telling that Thomas Nixon was one of the witnesses to the contract with the island bands, who knew exactly that for the Indians, Hecla, which was suffering from severe flooding during these years, was not an island at all. Black Island, which they called the Big Island, was their focus, not Hecla.

The Indians nevertheless had to submit to pressure from the interest group and signed the treaty. But since the colony on the Berens River did not flourish as the Methodists had expected, it was initially not known where to relocate it. In this location, the Dog Head Band , Bloodvein Band and Jack Fish Head Band were allowed to settle where they wanted. The Sandy Bar Band wished to join the group around Ka-Tuk-e-pin-ais.

In the late 1870s, some members of this Iceland band moved from Doghead to Loon Straits on the east bank of Lake Winnipeg, where they did horticulture. There, on the east bank of the huge lake, Indians live in Wanipogow today in a reservation on the mainland opposite Hecla. They are now called Hollow Water First Nation . More than 1,000 members of the nearly 2,000 people counted tribe living in 1,622.9 hectares large reserve Hollow Water 10 Indian Reserve .

Members of the Peguis First Nation (10,029 members, as of May 2016) and the Fisher River First Nation (3,848), who refer to the treaties with Canada, continued to retain their hunting rights, in particular to moose.

Two years after the Indians left Black Island, Methodist TA Burrows and his partner A. Walkey from Ottawa acquired the sawmill in Manigotogan on Black Island. In 1884 a dock was built on the southeast side of the island, but ultimately there was no economic exploitation.

Icelanders

In 1857 a British expedition to the Interlake region between Lake Winnipeg and Lake Manitoba determined that the flat, albeit wood-rich area was less suitable for settlement purposes than other areas in Manitoba. In 1875, shortly before the first Icelanders arrived, a Norwegian delegation considered the region unsuitable to settle there.

First settlers from Iceland

Nevertheless, Hecla was settled by Europeans from 1876 onwards. It was mostly Icelanders who called the island in Lake Winnipeg Mikley . Between 1870 and 1914, around 17,000 people, around 15% of the population, left Iceland to flee the economic hardship that was exacerbated by the eruption of the Askja volcano in 1875 , which poisoned the pastures in eastern Iceland. Instead of settling in the fertile area between Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipeg, however, the Methodist investors made sure that they moved further north. Thomas Nixon provided the first groups with tents and other equipment, Donald Smith provided them with boats, and John Schultz provided guides. The governor of Kewatin declared the area north of Hecla a reservation. At the same time, the Indians of the Berens River had to leave their area in favor of the Icelanders and relocate to the less fertile area on the Fisher River.

Sigtryggur Jonasson was probably the first Icelander to emigrate to Canada on his own, as there was still no organizational framework for those wishing to emigrate . He came to Québec on September 12, 1872 and became one of the leading figures in connection with the Icelandic emigration to Canada. According to the Icelandic Memorial Society of Nova Scotia, one of the first Icelanders was a Jóhann Eliasson Straumfjörd, who had left Hrisðalur in Hnappadalssýsla to Kinmount on the Burnt River in Ontario in 1874 . In 1874 he boarded the St. Patrick with 205 other Icelanders in Sauðárkrókur , in the north of Iceland - another 146 boarded in Akureyri - and sailed to Nova Scotia . In the fall of 1875 he went back to Iceland as an immigration agent, together with Johannes Árngrimsson, who called himself John Anderson. Eliasson moved to Mikley Island with his wife and two children in 1876. He was a homeopathic doctor, born in 1840 or 1842. He died in 1914, his wife Kristbjorg Jonsdottir, who was born in the same town, two years later.

But initially some Icelanders were stuck in the railroad company's homes in Kinmount, Ontario. Others had gone to Nova Scotia in search of work. For the Icelanders, who had specifically gone in search of a common Icelandic settlement, the realization that there would be no closed area for them was daunting. However, rumors reached them that 1,500 Mennonites had received land south of Winnipeg in Manitoba. Two Icelandic leaders, Sigtryggur Jonasson and John Taylor, took the initiative and negotiated with Ottawa. On June 30th, Einar Jonsson joined as the third guide for the long drive of all Icelanders in North America to Manitoba. Two Icelanders negotiated with compatriots in Milwaukee , where they were joined by Sigurdur Kristofersson, representing the Wisconsin Icelanders.

Taylor, Jonasson and Jonsson went with the other Icelandic representatives to Winnipeg on July 2, which they reached on July 16, 1875. As they moved further north, the six men witnessed the locust plague that year, a phenomenon that had destroyed agricultural yields as early as 1818-1820 and 1865-1868. The black, barren landscape did not scare the Icelanders, however, because they wanted to keep cattle and not grow grain. They learned from the settlers that Lake Winnipeg promised a lot of fish, that there was hay, lumber and berries there, but no locusts and only a few Indians. So they let three scouts from the Hudson's Bay Company lead them north. In October 1875 Ottawa let the Icelanders reserve the area, and negotiations with Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie about support for the poor settlers. But funds were only earmarked for immigration, not for migration between the provinces. But Governor General Lord Dufferin intervened on behalf of the Icelanders, since he had been deeply convinced of their "moral suitability" since visiting the island in 1856.

On September 25, 1875, 270 Icelanders left Toronto to enter the promised area. They took the train to Sarnia on the southern Huron Sea, then crossed the lake on the Ontario steamboat, which was completely overcrowded with people, cattle and luggage , crossed Lake Superior and after five busy days reached Duluth , where 13 other Icelanders joined them. Then the Northern Pacific went to the Red River . Then they drove with the International from Dakota to Winnipeg, which they did not reach until October 11th. The first settlement they wanted to found was to be called Gimli , meaning paradise . Icelanders had to leave the city of Winnipeg as quickly as possible, where food was becoming increasingly expensive thanks to locusts. But the difficulties were enormous. The trip across the lake was supposed to cost $ 1,200, a sum the community could not afford. Instead, she rented boats 5 m wide and 9 m long, which were otherwise used to transport timber. Each of them could take in 30 to 40 people with their property. Six of these Scows , with which they left on October 17th, were enough - between 50 and 80 Icelanders stayed in Winnipeg.

But the food they had bought was partially spoiled, rapids caused great problems, the Colville's propeller, which was pulling the 90 m long row of ships behind it, destroyed one of the boats. After all, there were enough poplars near today's town of Gimli on Lake Winnipeg to build houses that traditionally measured 3.5 by 3.5 m, some even 5 m. They were erected on the frozen ground and covered with grass; if the surrounding forest hadn't protected them from the wind, most of them would have frozen to death. Until then, many Icelanders had to spend the night in their boats while the sea was frozen. The ice was only safely accessible at the end of November. Others received tents from the Hudson's Bay Company, but they were in poor condition and many became ill. In December, the temperature on the lake fell below −40 ° C, making fishing impossible, especially since the new settlers did not master the techniques appropriate to this lake and its fish species. But the Winnipeg cattle that were to be brought in also found it difficult to reach the settlement, especially since a whole winter supply of hay had to be brought. When the idea to hunt moose came up, this also failed because other hunters had already shot the animals down.

After all, a school was established in which John Taylor's niece, Carrie, taught English to the children - almost none of the adults spoke this language - while she was learning Icelandic herself. In early 1876 Jon Gudmundsson brought out his first newspaper, Pjóðólfur , which was named after one of the leading newspapers in Reykjavík , and which he wrote by hand. However, the three editions have not been preserved. From April 20, fishing could be resumed, so that the starving colony recovered, in which 36 people had already died of hunger and scurvy . At the beginning of April there were only 100 Icelanders in Gimli, many looking for work in Winnipeg. In 1876 Fridjon Fridriksson founded a sort of placement agency for domestic staff, especially women.

But now more settlers came to Gimli. Sigtryggur Jonasson, who acted as Canada's first Icelandic settlement agent, had recruited settlers in Iceland, using severe volcanic eruptions that threatened the population's economic existence. In 1876 he brought around 800 Icelanders to America. They reached Gimli on August 20, seven weeks later. In the same summer, another 400 Icelanders came there, finally as a fourth group another 19 settlers came. Even if the figures diverge, around 1200 Icelanders should have reached the region within a year.

Only now did a group of ten Icelanders make their first contact with Indians. The ten lived on their foray north in a hut belonging to the Hudson's Bay Company, which they called “Pox” because it was here that smallpox broke out, which killed numerous Indians and some Icelanders. Only one white man named Ramsay lived nearby in a teepee with his wife and five children . He was added when the Indians and the Icelanders faced each other with weapons in hand, without any communication being possible. After Sigtryggur arrived with his settlers and a government official, the Indians and Ramsay respected the demarcation in favor of the Icelanders and left them alone. Ramsay was allowed to keep his tipi place and his garden, in which he also planted potatoes. From then on, he supported the settlers with his linguistic and cultural skills, but also with his ecological and local knowledge.

The settlement now stretched from Boundary Creek in the south to Sandvik in the north. The area up to the Icelandic River, as it was now called, was divided and populated. In the fall, the first settlers reached Hecla Island without the area being officially divided. They got into an argument with the sawmill owners there, who let them work without ever paying them, and confiscated the 200 tree trunks that were intended for a church. Sigtryggur Jonasson was the government agent for the colony from November 1876 to February 1877. Then a Colony Council took over the leadership.

Signs of smallpox were rampant in September, but it wasn't until November that it broke out in full. On November 27, two doctors dispatched by the government ordered the quarantine . It was only on April 7th that it could be determined that there were no more illnesses. By June 1877, the epidemic was finally contained. Every third settler was affected by the disease, 102 died, mostly children and young people. During the whole time, guards made sure that no one came into the colony and no one left without permission. Selling the fish or other goods and storing them were hardly possible under these circumstances. With the authorities still maintaining their quarantine, Icelanders gathered on July 20 to break the lockdown, but at that point it was lifted after ten months.

There were now 1,500 Icelanders living in the region, and around 150 to 160 had died. The settlers now divided New Iceland into four districts, which were given Icelandic names: Vidimes and Arnes districts, Fljots and Mikley districts. They consisted of 18 to 23 townships . With Framfari , the first printed newspaper New Iceland appeared, the last edition dated January 30, 1880.

Settlement of Heclas

Some settlers moved north, on Hecla. At first the Icelanders were supposed to live on the west bank of the island, but the flooding there was so severe that they preferred to move to the east bank, where higher settlements were available. In 1876 the first sawmill was built on Hecla, which attracted further settlers. With the money they earn there, they hoped to be able to pay for their fishing equipment. Although the sawmill often changed hands and was often idle, all the forest around Hecla was cleared after only five years. Therefore, the mill moved to Gull Harbor in the north of the island in 1881, where the owner went bankrupt. In the small town there was a lighthouse, opposite the Lighthouse Inn , later a small motel. A new sawmill was not built on Hecla until 1913.

In 1878 it looked like all Icelanders were going to migrate. The two warring Reverends Thorlakson and Bjarnson traveled through the Icelandic area serving the congregations. Thorlakson gave up Hecla and led about half of the families to North Dakota in 1880 , where Icelandic State Park is now at Cavalier . Of the original 26 homesteads on Hecla, only eight remained, but more settler families came from Iceland. 132 families preferred Bjarnson because, according to Icelandic tradition, he wanted to take care of his congregation even without a job (despite theological training). This had been sharply criticized by Thorlakson, on whose side 142 families stood, who adhered to the more fundamentalist and exclusive Norwegian teachings, which the Reykjavikers rejected.

Every house in Hecla was named after its owner, which meant that if the property changed hands, the new owner was given the old name. As early as September 1877, Riverton , which at that time was still called Lundi , published a first daily newspaper for the Icelanders in the area.

The region barely allowed arable farming, and attempts with wheat and rye failed. Therefore, the population lived largely from fishing, which is now a museum in the Hecla Fish Station . The men were often out and about for months in fish camps in the north, where mostly white fish were caught.

A wooden church was supposed to be built in 1878, but construction was delayed until 1890, as there was no agreement with the sawmill operator. The boards that had already been sawn were stolen without further ado. With the great emigration of 1880, schools in Gimli and Icelandic River were closed so the children were home-schooled until 1885. On Hecla, a teacher taught twenty children of the islanders for a salary of $ 9 a month. In 1890 the first church was built on the island. Pastor Magnus J. Skaptason wandered from district to district and looked after the four churches of the Icelanders. However, he resigned from office in 1891 when another dispute broke out within the Church.

In 1927 the church from 1890 was torn down and replaced by the one that exists today in order to accommodate the rapidly growing congregation. In 1897, the government lifted the rule that only Icelanders could live in the four districts, including Hecla.

Village development, fishing, ferry connections

One of the wealthier families became the Sigurgeirssons, whose log house has been preserved. Vilhjalmur Sigurgeirsson built boats, boxes and coffins and ran a general store in his house. There you got - often in exchange for fish - goods that you couldn't make yourself, such as sugar, flour or coffee. From 1913 he ran a sawmill that was powered by a specially brought-in steam engine. In addition to building materials for export to the south, the boxes required for packing the fish were also produced here.

The other fishermen in the village, which now has around 500 inhabitants, used small boats, known as skiffs , to go out onto the lake to catch fish; others took larger sailing boats to more distant areas of the vast lake. These Collingwood boats were replaced by motorized, wooden Whitefish boats in the 1930s . In order to be able to preserve the fish during the summer, ice houses were built. Large blocks of ice were cut out of the lake's ice in winter and brought to the ice houses on horses. The houses were insulated with hay and sawdust so that the fish stayed cold throughout the summer. The stored fish was loaded into boats twice a week and taken south, mainly to Winnipeg. In winter, from 1935 to 1962, this was done by freight gangs , groups of men who dragged the fish boxes, but also tree trunks and lumber across the frozen lake to Riverton , the nearest place on the mainland. The ice trails were kept free of snow by tractor-drawn plows and were increasingly used by cars and trucks.

In 1928, quartz and hematite were found on Black Island, the small neighboring island of Hecla , which were exploited in several experiments until the 1960s.

Overfishing, however, led to a collapse in fish populations, especially whitefish , golden eyes from the moon-eye family and glass eyeglasses . In 1969 the fishery was about to end, only 24 families lived on the island. 1970 to 1972 the lake was closed to fishing, the reason being that the mercury concentration was too high . The sawmill was closed because there were no more trees to speak of.

In the second half of the 20th century, the island's population largely emigrated, and the only school on the island was closed in June 1970. The Hecla Heritage Home Museum today offers an impression of the life of the settlers in the 20s to 40s, the Hecla School Interpretive Center of the school with its two rooms.

In 1953 a ferry, the Hecla Island Ferry under Captain Grimsi Grimolfson, began its service. His ship's mate was Halli Eastman, later Gunnar Tomasson. From 1958 two ships were used.

Provincial Park and Exodus

In the late 1960s, people pushed for a park to be set up in hopes of stopping the decline. In 1969 Hecla was raised to a provincial park and placed under protection. Significantly, the provincial park was initially jointly subordinate to the federal government and the province and was run by a Fund for Rural Economic Development , whose main task was the economic development of rural regions. In 1988 a first development plan was drawn up, which more clearly separated the areas that were to serve primarily for industrial or tourist destinations and the protected areas. According to this, the protected areas should represent the flora, fauna and geology of the region and be preserved. They should also secure relics of both Icelanders and the First Nations and make them accessible to the public. Recreational needs and the restoration of the elk population should be coordinated. It wasn't until 1997 that Grindstone was added to the park, which was now a provincial park.

However, the decline could not be stopped at first. In 1971 the ferry service introduced in 1953 was discontinued because a 3.2 km long road connected the island to the mainland. The government had refused to build the bridge because of the extreme climate, but some of the islanders, especially Dr. SO Thompson, who sat in the Manitoba Parliament , campaigned for it with success.

Electricity and cars, refrigerators and washing machines came to the island, but these had to be paid for, which was no longer possible with traditional work, especially fishing. Many islanders went to the cities to find work. Most did not return. In 1953 over 500 people lived on Hecla, in 1971 there were only 250.

Museums and accommodation on Hecla

The village of Hecla Village now consists of a fishing museum and facilities at the Hecla Fish Station next to the dock. Then there is the Tommasson Boarding House , the Community Hall ; the Hecla School with a replica of a classroom in one of the two rooms, an interpretive center for the park in the other. The Heritage House Museum - it was built in Sigurgeir Sigurgeirson's house from 1928 - is equipped with furniture from the 1920s to 1940s. It's maintained by the Descendants and Friends of Hecla , as is the General Store , another log cabin that housed the only store. It was opened by Gustaf Williams in 1932, but was demolished in 1959. Instead, the Tomassons' restaurant was moved to its current location and continued to operate as a shop until today. The Ice House Museum , which is a fishing, carpentry and forestry craft museum . Concerts are still held in the church in July and August.

Finally there is a bed and breakfast in a restored house and a number of private houses. The Gull Harbor Hotel with a conference center was built in Gull Harbor and reopened in 2008 as the Radisson Hecla Oasis Resort after the renovation . In the vicinity of the sandy beaches there are private summer houses, a marina (now the Lighthouse Inn) and an 18-hole golf course. There is a campsite next to the marina.

Ceremonial sites, hunting bans, protection of the elk herd

The local Indians visited their main island, Black Island, regularly until the 1920s, trying to protect their cemetery and ceremonial sites from road construction and tourism. Their camp was at the drumming point. However, with the potlatch ban of 1885, it became increasingly difficult to hold public ceremonies there. They had to leave Drumming Point and go to Wanipigow, but they continued to gather berries there and rarely used the island for healing and ritual purposes. Here, however, there was a revival in the 1970s, as in all of Canada.

From 1969 to 1978, big game hunting was banned, especially the populations on Hecla, estimated at 221 elk (out of 177 animals sighted) until 1978. However, since the herd has continuously shrunk since the mid-1980s, hunting was finally banned in 1989. Nevertheless, the herd continued to shrink and in 2000 only 25 animals were counted. The black bears were recognized as a further reducing factor. The increase in the bear population may have been related to the construction of the bridge to the island, as it was used by the predators that were previously rare on the island. Added to this was the attraction of the rubbish dump, which made the number of black bears rise to 20 to 30. Since the government gave priority to tourist use, the herd should be protected from too large a number of predators and at the same time wildlife observation posts should be set up.

National park plans, expansion to include Grindstone, endangerment

From 1994 to 1996 Canada and Manitoba discussed whether a national park should be set up from the area between the Great Lakes, i.e. between Lake Winnipeg and Lake Manitoba, the so-called Interlake, which should include other areas in addition to Hecla and Grindstone. However, a study came to the conclusion that the provincial park should not become a national park. In 1997, Grindstone was incorporated into the provincial park. Country houses (cottages) could still be maintained there.

There are over 400 privately owned houses on Grindstone, and the residents have held the Grindstone Days at the beginning of August every year since 1981 . There is a small general store. They have also run a local news paper , the Grindstone Gazette, since 1979 . In 2009, expansion work began along the bay on which the 417 houses stood. The expansion is to increase the number of places for the cabins to a total of 617 by 2013 .

At the end of 2011, Sun Gro Horticulture applied for a permit to intervene in the highly endangered flood protection system of Lake Winnipeg. In the Hay Point Bog, a moorland at Grindstone Point, peat was to be cut on an area of 531 hectares for 45 years. The residents sued the project. According to the Wilderness Committee, the mining is endangering the largest elk area in southern Manitoba, the Washow-Fisher Peninsula. In February 2013, the provincial government banned all peat cutting in the provincial parks.

In August 2000, archaeological investigations took place on the occasion of the annual Hollow Water Culture Days on Black Island. Many students from the Hollow Water community took part in the excavations.

Landscape, fauna, flora

Coniferous and mixed forests - poplar, birch and spruce predominate -, limestone cliffs and sandy beaches, marshes , moors , raised bogs and wet meadows determine the landscape. The park represents the so-called Mid Boreal Lowlands of the Manitoba Lowlands . This also includes marshes, which, however, have been destroyed many times by electricity generation on the Nelson River and other projects. As a result, after a road was laid in 1977 that separated the area from Lake Winnipeg , Ducks Unlimited and Manitoba Conservation built a system of dykes to preserve the Grassy Narrows that are used as breeding grounds for migratory birds. In 1975 about 50,000 of them were counted. The area is managed by Ducks Unlimited (Canada), an organization that also created the three hiking trail systems. These are the short Wildlife Viewing Tower Trail , which mainly allows the observation of moose, and the adjacent Grassy Narrows Marsh Trails in the southwest, then the 3.5 and 10 km long West Quarry Trail in the north of Hecla, and finally the Gull Harbor Trails , a system of paths to which the Lighthouse Trail belongs in particular . The latter leads over a narrow peninsula between Gull Harbor and Lake Winnipeg Narrows, the narrowest part of the lake.

In addition to numerous species of birds , there are black bears , elks , beavers , muskrats , foxes and coyotes , otters, lynxes, wolves and various deer species, but also amphibians and turtles, as well as bald eagles in the trees along the coast. In addition, there is a growing number of pelicans, falcons, hummingbirds, woodpeckers, owls and various types of ducks.

Rhinoceros pelicans ( Pelecanus erythrorhynchos ), here called American White Pelicans , settle on numerous small rocks, the Pipestone Rocks, but also the Kasakeemeemisekak Islands (Cree: "many islands"). The former are bare due to the input of guano . Around 1% of North American pelicans breed on these rocks; 1,500 animals were identified as early as 1990. They hunt fish in a division of labor, ie they use drivers and catchers. Small schools fish within a radius of more than 100 km. Their stocks were increasingly endangered from around 1900, first because of the massive hunt for them, since they were mistakenly viewed as competitors for the fishermen, then because of the use of DDT . Around 1975 they were considered threatened, but the all-clear was given in 1987. The predominant gulls are the Canada gull ( Larus smithsonianus ) and the ring-billed gull ( Larus delawarensis ), whose nests on the Pipestone Rocks are estimated at 8,000.

The rocks are also used by cormorants , seagulls and terns. During the breeding season from May to August, people are not allowed to visit the rocks. In 2006 there were 10 to 13 pairs of the yellow-footed plover ( Charadrius melodus circumcinctus ). In the marshland you can also find the sedge and the swamp wren , the yellow-headed blackbird ( Xanthocephalus xanthocephalus ) as well as tommels , which are rare in Canada , but also nelson hammer ( Ammodramus nelsoni ) and leconteammer ( Ammodramus leconteii ).

The Pipestone Rocks are particularly worthy of protection and are deprived of any economic use, in particular logging, mining and hydroelectric use. They are considered candidates for Ecological Reserves status , which is the highest protected status in Manitoba. There are also plans to pass it over to federal ownership as a national park. In 2009, there were 209 breeding bird species in the southern Interlake area between Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipeg.

On the northeast side of Black Island there are numerous small islands around the somewhat larger Cairine Islands , where other birds breed.

In the summer of 2001, the twelve black bears were temporarily removed from the island to see how the elk population was recovering (grizzly bears have not been on the island since the late 19th century). In addition, both human-induced factors and the role of timber wolves were examined. From 1971 to 1989, between 17 and 46 calves were counted each year; in 1996/97 there were only four, and in 2000 not a single one. In order to increase the chances of survival of the few calves that sometimes fall prey to bears in the first six to eight weeks, the bears should be removed from the island for some time. They were mainly released west of Lake Winnipeg, some also to the east. There was only one specimen of the Timber Wolves on Hecla. However, wolves cross the lake's ice every winter. Their whereabouts in summer depends on where they are at the time of the ice melt. At the end of the 1980s, two small packs of 7 to 9 or 3 to 4 animals were expected; in 1999 there was only one pack with 7 to 9 animals. Research led to the assumption that generations of dependence on Icelandic fish waste and hunting resulted in them losing the skills necessary to hunt moose . Bears, on the other hand, were extremely rare until 1979, so that it was assumed for this year that only one black bear lived on the island; since bears hibernate, they could only swim to the island. But with the construction of the bridge and the dump, their number increased. Between 1994 and 1999, an average of four bears were removed or shot every year.

Some of the tributaries of Lake Winnipeg suffer from over-fertilization, so that a strong increase in algae populations has been observed for some years. This applies in particular to the sea area north of Hecla and, for some years now, also south, so that the authorities are issuing warnings to warn of the dangers of the sometimes toxic algae. Bathing bans were first issued in 2003. These operations prompted the provincial government, it said, to do more to purify sewage and restore wetlands and marshes.

Some amphibian and reptile species find their ultimate refuge on the island, such as the western ornamental turtle or Indian turtle, here called Western Painted Turtle ( Chrysemys picta bellii ), which finds its northernmost habitat here. The park also marks the edge of their range for the Canadian toad ( Anaxyrus hemiophrys ) and the American toad ( Anaxyrus americanus ). The same applies to the endangered tree frog Hyla versicolor , which can still survive at −8 ° C.

48 species of fish live in Lake Winnipeg, plus four that have been introduced by humans (including arctic smelt ( Osmerus mordax ), carp and moron chrysops , a type of sea bass ). The various whitefish , the Canadian and the glass eye perch are commercially important - for the latter, the reefs on the south coast of Hecla are particularly important as a spawning area. There are also pike, the American perch , the perch species Percopis omiscomaycus (trout perch), the burbot , the freshwater drumstick , the American whitefish ( Coregonus artedi ), Notropis atherinoides (Emerald Shiner) and golden-eye (Hiodon alosoides ) the family of the moon eyes . Numerous Rhinichthys cataractae live off the east coast of the island and belong to the Leuciscinae , a subfamily of carp fish . They 're called the Longnose Dace here . Endangered species Macrhybopsis storeriana (Silver Chub) from the family Cyprinidae, bigmouth buffalo (Ictiobus cyprinellus) from the family of Redhorse , Coregonus zenithicus (Shortjaw Cisco) in the genus Coregonus and Ichthyomyzon castaneus (Chestnut lamprey), a Neunaugenart .

Black Island has the westernmost and northernmost population of the American red pine or red pine ( Pinus resinosa ), a tree species that is still represented here with specimens up to 150 years old, despite logging from the late 19th century. It is a mixed forest in which, in addition to the red pine, Banks pine , black spruce , balsam fir ( Abies balsamea ) and paper birch ( Betula papyrifera ) as well as common juniper ( Juniperus communis ) thrive.

literature

- Archaeological Investigations on Black Island During Hollow Water First Nation Cultural Days , digital manuscript, Northern Lights Heritage Services Inc., Winnipeg 2001.

- Patrick H. Carmichael: A Descriptive Summary of Blackduck Ceramics from the Wanipigow Lake. Site Area , Historic Resources Branch, Manitoba Dept. of Tourism, Recreation and Cultural Affairs, Winnipeg 1977.

- Jónas Þór: Icelanders in North America. The First Settlers , University of Manitoba Press 2002.

- Raymond E. Kotchorek: Response of Moose Calf Survival to Reduced Black Bear Density. An Assessment of the Stresses likely Affecting the Moose Population on Hecla Island , Thesis, University of Manitoba 2002.

- Arnie Waddell: A spatial analysis of tourism development on Hecla Island in relation to key environmental components , University of Manitoba 2000.

- Management plan for Hecla Provincial Park and Grindstone Provincial Recreation Park , ed. By Manitoba Parks Branch, Department of Natural Resources, 1988 ( online , PDF (19.1 MB)).

Web links

- Manitoba Conservation - Hecla / Grindstone Provincial Park

- Boreal Forest Woodland Period. Wanipigow Site EgKx-1

- Grindstone Park. Grindstone Cottage Owners Association (January 18, 2016 memento on the Internet Archive ), Grindstone Cottage Owners Association , archive.org, January 4, 2014

- Steinunn J. Sommerville: Early Icelandic Settlement in Canada , The Manitoba Historical Society

Remarks

- ↑ Investigation of Hecla Island and Property Transactions , ed. Auditor General, Winnipeg, August 2003, pp. 36 and 67.

- ↑ The length is taken from the article Lake Winnipeg in the Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ This and the following according to Arnie Waddell: A spatial analysis of tourism development on Hecla Island in relation to key environmental components , University of Manitoba 2000, pp. 13-15.

- ↑ Alanna Sutton, Richard J. Staniforth, Jacques Tardif: Reproductive ecology and allometry of red pine ( Pinus resinosa ) at the northwestern limit of its distribution range in Manitoba, Canada , in: Canadian Journal of Bot. 80 (2002) 482-493 , here: p. 485.

- ↑ Manitoba Provincial Heritage Site No. 6, Wanipigow Lake Archaeological Site, (EgKx-1), Township 24, Range 12 E, Lake Wanipigow

- ↑ Manitoba Provincial Heritage Site No. 6, Wanipigow Lake Archaeological Site, (EgKx-1), Township 24, Range 12 E, Lake Wanipigow

- ↑ Manitoba Provincial Heritage Site No. 6, Wanipigow Lake Archaeological Site, (EgKx-1), Township 24, Range 12 E, Lake Wanipigow .

- ↑ George F. Reynolds: La Verendrye and Manitoba's First Mine , in: Manitoba Pageant, Spring 1971, pp. 2–7, here: p. 3.

- ↑ Virginia Petch, Linda Larcombe, David Ebert, K. David McLeod, Gene Senior, Matthew Singer: End of Field Season Report. Testing the F1 Archaeological Predictive Model , report prepared for The Manitoba Model Forest Inc. , January 2001, p. 54.

- ^ Treaty 5 between Her Majesty the Queen and the Saulteaux and Swampy Cree Tribes of Indians at Beren's River and Norway House with Adhesions .

- ↑ The Illegal Surrender of the St. Peter's Reserve. A Report Prepared for: the TARR Center of Manitoba, Inc , 1983.

- ^ Sarah Carter: Site Review: St. Peter's and the Interpretation of the Agriculture of Manitoba's Aboriginal People , The Manitoba Historical Society, 1989.

- ↑ George Young: Manitoba Memories . William Briggs, Toronto 1897, p. 293.

- ^ Frank Tough: 'As Their Natural Resources Fail'. Native People and the Economic History of Northern Manitoba , University of British Columbia Press 1996, p. 149. The contract reads: “We, the Band of Saulteaux Indians residing at or near the Big Island and the other islands in Lake Winnipeg, and also on the shores thereof, having had communication of the aforesaid treaty, of which a true copy is hereunto annexed, hereby, and in consideration of the provisions of the said treaty being extended to us, transfer, surrender, and relinquish to Her Majesty the Queen, Her heirs and successors, to and for the use of the Government of Canada, all our right, title and privileges whatsoever, which we have or enjoy in the territory described in the said treaty, and every part thereof, to have and to hold to the use of Her Majesty the Queen, and Her heirs and successors forever. "

- ↑ Norman James Williamson: Black Island: The Indian Reserve that never was. The Methodists and the Indians .

- ↑ According to the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Hollow Water ( Memento from May 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) there were exactly 1,767 recognized tribesmen in February 2012, of whom 1,128 lived on the reservation; In May 2016, 1,011 of the 1,921 relatives were still living in the reserve.

- ↑ Peguis ( Memento of May 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Fisher River ( Memento from May 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Margaret McWilliams: Manitoba Milestones . JM Dent and Sons, Toronto 1928, p. 124.

- ↑ : Sigrún Bryndís Gunnarsdóttir Icelandic Immigrants and First Nations People in Canada , Háskóli Íslands, Hugvísindasvið Enska, 2010, p. 19.

- ^ Gunnar Karlsson: The History of Iceland , University of Minnesota Press 2000.

- ↑ The Askja .

- ↑ Jónas Thor: Icelanders in North America. The First Settlers , University of Manitoba Press 2002, p. 27.

- ^ The Emigration from Iceland to North America, Passenger List of the SS St. Patrick, 1874 ( Memento of April 2, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), archive.org, April 2, 2010.

- ↑ Eliasson appears on the SS St. Patrick's passenger list : Montreal Ocean Steamship Company ( Memento of April 2, 2010 in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Markland Families After 1879 , website of the Icelandic Memorial Society of Nova Scotia .

- ↑ This and the following according to Jónas Þór: Icelanders in North America. The First Settlers , University of Manitoba Press 2002, Chapter 5, pp. 78ff.

- ↑ Jónas Þór: Icelanders in North America. The First Settlers , University of Manitoba Press 2002, Chapter 5, p. 81.

- ↑ Jónas Thor: Icelanders in North America. The First Settlers , University of Manitoba Press 2002, p. 164.

- ↑ Jónas Þór: Icelanders in North America. The First Settlers , University of Manitoba Press 2002, Chapter 5, p. 106.

- ↑ On the religious division of the Icelandic community cf. Erla Louise Colwill Anderson: Tolerance, intolerance, and fanaticism, WD Valgardson's reaction to the religious debate in New Iceland , University of Manitoba 2000.

- ↑ Jónas Þór: Icelanders in North America. The First Settlers , University of Manitoba Press 2002, Chapter 5, p. 208.

- ^ Liza Piper: The Industrial Transformation of Subarctic Canada , University of British Columbia Press 2009, p. 85.

- ^ Arnie Waddell: A spatial analysis of tourism development on Hecla Island in relation to key environmental components , University of Manitoba 2000, p. 14.

- ^ Community Hall - Hecla / Grindstone Provincial Park

- ↑ Investigation of Hecla Island and Property Transactions , ed. Auditor General, Winnipeg, Aug 2003, p. 36.

- ↑ Investigation of Hecla Island and Property Transactions , ed. Auditor General, Winnipeg, August 2003, p. 64.

- ↑ Investigation of Hecla Island and Property Transactions , ed. Auditor General, Winnipeg, Aug 2003, p. 66.

- ↑ Kotchorek, 1-3.

- ↑ Investigation of Hecla Island and Property Transactions , ed. Auditor General, Winnipeg, Aug 2003, p. 68.

- ↑ Grindstone Gazette 138 (March 2009), p. 1.

- ^ Application dated October 28, 2011 , PDF.

- ↑ Map with the location of the planned peat cutting facility , plus other raw material mining activities.

- ↑ Manitoba News Release , February 25, 2013.

- ^ Arnie Waddell: A spatial analysis of tourism development on Hecla Island in relation to key environmental components , University of Manitoba 2000, p. 16.

- ↑ Important Bird Areas Canada .

- ↑ Alexandra Miller: Manitoba Piping Plover Stewardship Program: a provincial strategy for the management of the endangered piping plover (Charadrius melodus circumcinctus) , University of Manitoba, 2006, p. 11.

- ↑ Stacey Hay: Distribution and Habitat of the Least Bittern and Other Marsh Bird Species in Southern Manitoba , thesis, University of Manitoba 2006.

- ↑ Important Bird Areas Canada , Section Conservation Issues .

- ↑ Manitoba Breeding Bird Atlas ( Memento April 30, 2015 in the Internet Archive ), archive.org, April 30, 2015.

- ↑ Kotchorek, p. 4.

- ↑ Green slime can be toxic, experts say , in: Winnipeg Free Press, August 11, 2010.

- ↑ Memorandum of the Governments of Canada and Manitoba (English version; PDF file; 1021 kB), French. Version (PDF file; 1.08 MB).

- ^ Arnie Waddell: A spatial analysis of tourism development on Hecla Island in relation to key environmental components , University of Manitoba 2000, p. 17.

- ↑ John H. Gee, Kazimierz Machniak: Ecological Notes on a Lake-Dwelling Population of Longnose Dace (Rhinichthys cataractae) , in: Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 29 (1972), pp. 330-332.

- ↑ Alanna Sutton, Richard J. Staniforth, Jacques Tardif: Reproductive ecology and allometry of red pine (Pinus resinosa) at the northwestern limit of its distribution range in Manitoba, Canada , in: Canadian Journal of Bot. 80 (2002) 482-493 , here: p. 484.