Hippocampus Debate

a) posterior lobe

b) lateral ventricle

c) posterior horn

x) lesser hippocampus.

The hippocampus debate was a controversy between British biologists Richard Owen and Thomas Henry Huxley about the taxonomic classification of humans in the animal kingdom .

It was in the summer of 1860, two days before the Huxley-Wilberforce debate , at the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Oxford triggered as the most important British anatomist Richard Owen repeated the argument that the human being from the other that primates by Certain morphological peculiarities in the brain structure , in particular the presence of a hippocampus minor , differentiate and it forms a separate subclass in the class of mammals . In the discussion, Thomas Henry Huxley opposed this view and promised to refute Owen's claim.

Initially initiated in part by Huxley, a series of scientific studies on primate brains appeared that contradicted Owen's representations. However, Owen repeatedly insisted on his assessment of the test results. The controversy, which was followed with great interest by the British public, ebbed in 1863 after the publication of Huxley's work Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature .

The public dispute between the "British Cuvier " Owen and " Darwin 's Bulldog" Huxley was an important step in the recognition of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and damaged Owen's reputation as a scientist.

Hippocampus minor

The lesser hippocampus is located in the lateral ventricle of the endbrain . It is a protrusion of the medial wall of the posterior horn (cornu posterius) located in the occipital lobe , which is formed by the deeply cutting calcarina (also known as the spur groove). Since it is reminiscent of the spur of a bird, it was given the name Calcar avis .

When the brain nomenclature was revised in 1786, Félix Vicq d'Azyr renamed the calcar avis to Hippocampus minor . The 1564 Giulio Cesare Aranzi discovered hippocampal he described, however, as hippocampus major . In 1779 Johann Christoph Andreas Mayer erroneously used the term "hippopotamus" ( hippopotamus ) in a work . Other authors repeated this error until Karl Friedrich Burdach clarified the matter in 1829. Until the end of the 19th century, calcar avis and hippocampus minor were synonymous in use.

prehistory

Living apes there until the early 1830s in European zoos hardly. London Zoo in Regent's Park , founded in 1828, received its first orangutan in 1830, the first chimpanzee in 1835 and the first gibbon in 1839. The young orangutan died of pneumonia just three days after arriving from India . Richard Owen examined the carcass and published the results in the first scientific paper of his career. The chimpanzee, introduced from Sierra Leone in 1835 , also died quickly and Owen was given permission to examine the animal. Owen found that the skeleton of the chimpanzee resembled that of humans more than that of the orangutan, but rejected the thesis put forward by Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck that humans are descendants of the ape.

Owen, since 1856 Superintendent of the natural history collection of the British Museum and through his numerous publications, a recognized authority in the field of osteology of the primates, held on 17 February and 21 April 1857, two lectures before the Linnaean Society of London . Like Charles Lucien Bonaparte before him, he proposed that mammals be classified according to features of the brain . Owen distinguished four subclasses of mammals. The lowest level of development of the brain is formed by the subclass "Lyencephala" (ie loosely connected parts of the brain). This is characterized by the fact that the two halves of the brain are relatively small and usually smooth on the outside and only loosely connected to one another by transverse tracks. The monotremes and the marsupial mammals belong to it . The next stage of brain development is represented by the subclass "Lissencephala" (i.e. smooth brains) to which rodents , shrews , bats and sloths belong. With them, the halves of the brain are connected by a beam . The surface of the brain is smooth and has few or no brain convolutions. The next evolutionary step of the brain, the subclass "gyrencephala" (that is, coiled brains), is characterized by a relative increase in the size of the brain. These brains extend more or less far over the cerebellum , and their surface usually has numerous brain convolutions . In this subclass belonging hoofed animals , whales , carnivores and the duet ( "Quadrumana"), so the apes , monkeys and lemurs . As the only species Owen put humans in the fourth subclass "Archencephala" (i.e. ruling brain). The human brain shows a sudden increase in the relative and absolute size of the hemispheres and the volume of the skull. "Humans alone have a third lobe in the rear, a rear horn on the side chamber and a brain region called the hippocampus minor ."

In contrast to Carl von Linné's view, who placed humans in the order of primates , Owen followed a suggestion by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach who, in his work Handbuch der Naturgeschichte in 1779, created the order "Bimana" (two-handed) for humans and all other primates assigned to the order "Quadrumana" (four-handed). This point of view was later popularized in particular by Georges Cuvier . In a letter to Joseph Dalton Hooker , Charles Darwin commented on Owen's special position of humans with the words: "I want to know what a chimpanzee would say about it."

Thomas Henry Huxley, professor of paleontology at the Royal School of Mines since 1854 , was among the audience at Owen's lectures in 1857. After the events he began to deal with anthropological topics. His lecture series The Principles of Biology , which he held in the first quarter of 1858 in front of the Royal Institution , he added in the spring of 1858 to a lecture on " The Distinctive Characters of Man" . Before illustrations and brains were from people, gorillas and baboons, he concluded: "the difference between gorilla and human being as an animal much smaller than that between gorilla and Yellow Baboon ". In another lecture given to the Royal Institution in February 1860 by Huxley on "Species and Races and Their Origins," which was devoted to Darwin's theory, he again stated that "the anatomical difference between man and the most developed Four-handed is less than the difference between the most extreme species within the order of the four-handed. "

Course of the debate

Oxford 1860

The annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS) took place in Oxford in the summer of 1860 in the rooms of the new Oxford University Museum of Natural History . On June 28, 1860, Charles Daubeny gave a lecture to Section D, responsible for zoology and botany, including physiology, on the sexuality of plants, with particular reference to Charles Darwin's work The Origin of Species , published at the end of November 1859 . John Stevens Henslow , who held the presidency of Section D, asked Huxley to speak up. However, Huxley declined to address the assembled audience. Owen, who at that time was one of the few European primate experts and was regarded as the highest authority for primate osteology (bone science), took the floor and repeated the statements he made in 1857 about the special position of humans in the animal kingdom: Only humans are wise In the rear area, a third lobe of the brain, a rear horn on the adjoining chamber and a hippocampus minor and therefore form a separate subclass. In his contribution to the discussion, Owen openly attacked Huxley's position on the question of the position of humans in the animal kingdom. Huxley, who felt challenged by Owen's allegations, responded with a direct and unqualified contradiction and promised elsewhere to justify himself for his unusual approach.

Huxley's "Natural History Review"

Huxley used in particular the content-reoriented journal Natural History Review , the editor of which he had taken over in 1860, as a platform for his reply. In the first edition, published in January 1861, he published an article " On the Zoological Relations of Man with the Lower Animals", and for the first time since the controversy began, he commented on Owen's views . The article began with the epistemological question, "What is the relationship between the thinker and the researcher to the subject of his research". He argued that theologians, historians, and poets only saw the great gap between humans and animals and therefore wanted to separate humans from the animal kingdom, whereas scientists disagree and emphasize the close bond that binds humans with their lower relatives. He emphasized that both views concern different phenomena in human society, but the zoological classification of humans in the animal kingdom is the sole task of science. Huxley then cited numerous studies on the real monkey carried out in mainland Europe . These showed that the third lobe (posterior lobe) covered a large part, or even the entire part, of the cerebellum of the monkey species examined. From the same studies, he gave numerous examples of the presence of the dorsal horn and the minor hippocampus . Huxley concluded that the differences between the highest and lowest races of humans were of the same order of magnitude as those that distinguished the human brain from the monkey brain. Huxley himself had not done any research on monkey brains. Even before the BAAS meeting in Oxford, however, he had written a letter to Allen Thomson (1809-1884), Professor of Anatomy at the University of Glasgow , who had recently dissected a chimpanzee brain. Thomson replied on May 24, 1860, that the young female chimpanzee he dissected had a well-defined posterior lobe that covered the cerebellum . Huxley quoted extensively from this letter.

Gorillas

Because of its resemblance to humans, the gorilla has become a central part of the debate about the position of humans in nature. In 1846 the missionary Thomas Staughton Savage (1804–1880) discovered the skull of a great ape in what is now Gabon , which was believed to be a new species of chimpanzee. With the help of the American Jeffries Wyman , the first scientific description was made in 1847 under the name Troglodytes gorilla . In the same year, Owen managed to obtain two skulls of the new great ape from the Philosophical Institution of Bristol , for which he proposed the name Troglodytes Savagei in 1848 . Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire recognized in 1852 that it was a new genus of great ape and gave it the name gorilla .

In 1849 Owen compared the skull structure of gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans and humans and already at that time emphasized the special taxonomic position of humans. In 1851 the Hunter Museum received a complete skeleton of a gorilla, which Owen immediately examined. He published his results in two lectures. The first completely preserved carcass of a gorilla preserved in alcohol was given to the British Museum on September 10, 1858. This gave Owen the opportunity to study the entire anatomy of a gorilla. His research made it clear that the anatomy of the gorilla differs significantly from that of the orangutan and chimpanzee and is more similar to that of humans. Owen realized that the gorilla's feet are better adapted to walking than the orangutan and chimpanzee. Like humans, in contrast to all other apes, it has a mastoid process . In a lecture on February 4, 1859, given to life-size drawings of the gorilla and chimpanzee by Joseph Wolf at the Royal Institution , Owen came to the conclusion that the gorilla is the most human-like ape and that it is closer to humans than the chimpanzee. At the same time, however, he emphasized that there are over thirty essential differences in the skull and teeth alone.

The twenty-year-old Paul Belloni Du Chaillu began an almost four-year expedition to Central Africa in 1856 with the support of the Academy of Natural Science of Philadelphia . In addition to numerous ethnographic observations and an extensive collection of birds and mammals that he brought back with him, in his travel report Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa he gave a precise, up to then unique description of the behavior of the western lowland gorilla in its natural environment. A few years later, however, his observations turned out to be flawed. At the end of December 1860, Du Chaillu wrote to Owen and offered him parts of his collection. In February 1861 Du Chaillu traveled to London. There Owen helped him with the publication of his travelogue, bought part of the collection of Du Chaillus gorilla skins for the British Museum and gave him lectures at the Royal Geographical Society , the Ethnological Society of London and the Royal Institution.

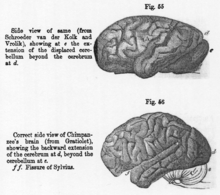

The day after Du Chaillu's lecture on March 18, 1861 at the Royal Institution, Owen repeated his claims about the unique structure of the human brain in a lecture reproduced in The Athenaeum on March 23, 1861 . In a letter published a week later in the Athenaeum , Huxley briefly pointed out an incorrect figure and made it clear that all previous anatomists, including Owen himself, had described the controversial three features in the brains of monkeys. Owen replied in the next edition that his lecture, with the exception of the illustration, had been reproduced correctly, and in turn referred to the illustration of the chimpanzee brain in his "Reade Lecture" of 1859. Huxley, who felt provoked by Owen's comment, made in the next edition of the Athenaeum of April 13, 1861, pointed out that he had already mentioned in his January article that Owen had taken the images of the chimpanzee brain from an article by Jacobus Schroeder van der Kolk (1797–1862) and Willem Vrolik , but without going into the origin of the figure. The French anatomist Louis Pierre Gratiolet had already made it clear in 1855 that the illustration of van der Kolk and Vrolik was incorrect and showed an incorrectly conserved and thus shrunken chimpanzee brain.

Huxley's supporters

Huxley's contradiction at Oxford aroused the admiration of George Rolleston , who had just been appointed the first Linacre Professor of Physiology at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History . He examined the brain of a young orangutan and compared it to human brains kept in the Oxford University Museum. He made detailed size measurements on them and found no significant differences.

John Marshall , a doctor at University College Hospital in London, received the carcass of a young male chimpanzee 24 hours after the death and immediately performed a brain examination. He emphasized that the brain could be greatly deformed if it was preserved in ethanol without hardening it beforehand . All larger parts of the brain have their homologous counterparts in the chimpanzee. With regard to the three particular parts of the brain, his result agreed with those of Thompson and Huxley.

Two months later, when Owen again used one of van der Kolk's and Vrolik's illustrations to illustrate his claim, the two authors spoke up and pointed out that they had described the brain structures Owen denied in the text of their article. In August 1861 they both dissected an orangutan that had died in the Amsterdam zoo and found all three brain structures claimed by Owen only for humans.

William Henry Flower , anatomy demonstrator at Middlesex Hospital , read in January 1862 before the Royal Society an extensive paper based on studies of monkeys and great apes that had died in the zoo of the zoological society in the summer of the previous year. He compared the brains of 18 species of primates and other mammals such as cats, dogs and horses. In many of the old world monkeys , new world monkeys , and wet-nosed monkeys examined , the posterior lobe was proportionally larger than in humans. This also applied to the strikingly developed minor hippocampus .

Huxley himself examined the brain of the red-faced spider monkey , a morphologically very different New World monkey from humans , and presented his results on June 11, 1861 at a meeting of the Zoological Society . Owen's three brain peculiarities were not only present, they were even more pronounced than in humans.

Cambridge 1862

The hippocampal debate reached its climax at the BAAS meeting in Cambridge at the end of September 1862 under Huxley's chairmanship. Owen gave two lectures in front of "Section D". In his lecture on the finger animal , he doubted that Darwin's theory could explain the elongated third finger of the finger animals. In the second lecture, Owen compared the structure of the gorilla's brain and foot with those of humans. With regard to the brain, he found that the hemispheres did not extend beyond the endbrain and that the brain was much smaller in relation to body size than that of humans. Without naming names, he criticized Huxley's position that the difference between humans and gorillas is not as great as the difference within monkeys and that the differences in the structure of the brains can be used as a means of zoological classification. The debate that followed Owen's lecture was very lively. Huxley spoke first. He turned to the anatomists gathered in "Section D" with the question of whether Owen's position had not been refuted clearly enough in the past by continental European and British anatomists. He stressed that the differences between humans and animals are spiritual. Flower clarified that the difference between monkey and human brains was not to be found in the posterior lobe and the minor hippocampus . Rolleston, who apologized for the ferocity of the attack, accused Owen of overlooking the work of foreign anatomists like Gratiolet. Triumphantly, Huxley wrote to Darwin: "All those present who could judge saw that Owen was lying and messing everything up".

An article in the Medical Times and Gazette reporting Owen's presentation drew additional letters from those involved. Rolleston wrote a letter in which he deepened his impromptu speech at the BAAS meeting. A week later, a letter was published from Huxley briefly summarizing the history of the controversy, accusing Owen of "playing an unworthy game of truth," and stating that "not a single major or minor anatomist supports Professor Owen have".

Results of the debate

For Huxley, the hippocampus debate came to a successful conclusion four months after the heated argument in Cambridge with the publication of his work Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature (German title: Evidence for the position of man in nature ). Huxley began his remarks with a historical account of the discovery and description of the human-like apes. He then commented on the similarity of the early stages of embryonic development in numerous mammals to show that the development of human and monkey embryos were more similar than the development of monkey and dog embryos. The relationship turns out to be similarly close when comparing the skeleton and skull. Huxley showed that from an anatomical point of view, monkeys have feet and hands like humans. He concluded by stating that "the question of man's attitude to lower animals ultimately emerges in answering the more important question of the durability or the untenability of Mr. Darwin's views." After a brief summary of his controversy with Owen, Huxley turned to it in a third chapter the few human fossil finds known until then, the “ Engis skulls” (Engis 1 and Engis 2 ) discovered by Philippe-Charles Schmerling in 1829 and the Neanderthal man examined by Hermann Schaaffhausen in 1857 . Huxley emphasized that assuming that humans developed from an ape-like ancestor, this would have happened over a very long period of time. Huxley's testimonies to the position of man in nature are considered the first consistent application of Darwin's teaching to man.

At about the same time as Huxley's work, Charles Lyell's Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man appeared (German title: The age of the human race on earth and the origin of species ). Antiquity of Man was divided into three large, more or less independent sections. The first twelve chapters dealt with the age and early history of humans, the next seven chapters with glaciers and the last five chapters with evolution . In Chapter 24, on the importance of transmutation theory in relation to the origin of man and his place in nature , Lyell gave a succinct and concise account of the controversy, showing that Owen's views both regarding man’s position in the animal kingdom and the alleged position Differences in the structure of the brains in humans and monkeys are wrong. Hooker and others suggested that the chapter on the hippocampal debate in Lyell's work was written by Huxley. Lyell, who like many of Darwin's followers, had an aversion to Owen, had indeed stated in a letter to Huxley that Owen had to be "nailed down" and had asked him for material on the hippocampal debate for his new work. Lyell received the manuscript of Testimonies for the Position of Man in Nature from Huxley in advance .

In a letter addressed to and published in The Athenaeum , Owen attacked Lyell. Owen claimed, in reverse of the facts, that in 1861 he published the pictures by van der Kolk and Vrolik only because he wanted to show how close the monkey brain came to the human one. Lyell was defended by George Rolleston, who in the next issue of the magazine referred to his own arguments and his own role in the debate. Lyell responded to Owen's allegations two weeks later. He quoted from a letter that William Henry Flower had sent to him in which Flower Lyell certified a "very fair and moderate summary of this controversy". The publisher John Murray described Owen's letter as an "octopus attack" because Owen hid his real intentions behind a cloud of ink.

For the new edition of the Dictionary of Science, Literature and Art, Owen added the following sentence to the entry on the minor hippocampus in 1866 : "No structure of this kind, which corresponds in position and form to the definition of the anthropotomists, has been discovered in any monkey." Owens concludes A comment on the hippocampus debate took the form of a long footnote in the second volume of his work On the Anatomy of Vertebrates , published in 1866 . In it he stated that, as he and others had shown, "all homologous parts of the human brain existed in a modified form and less pronounced in the Quadrumana ," and described the attacks by Huxley and his allies as "childish", "ridiculous" and "shameful".

The vehemence of Huxley's and his supporters' countermeasures, as well as the contradictions in which Owen became entangled during the argument, severely damaged Owen's scientific reputation. From around 1868, his scientific writings no longer played a role in the debate about Darwin's theory of evolution. In the remaining years of his life, Owen essentially devoted himself to his plans to establish an independent natural history museum, which culminated in the construction of the Natural History Museum . In a letter on the hippocampus debate, which Owen wrote to Henry Acland (1815–1900) in October 1862 , Owen noted in a postscript about his argument with Huxley: “Do you remember the stories of the clever young Athenian, who wanted to be a celebrity? He went to the oracle and asked, 'What do I have to do to become a great man?' Answer: 'Slay one!' "

reception

Contemporary reception

In October 1862, a few days after the meeting of Huxley and Owen in Cambridge, the British Medical Journal asked the two adversaries to stop their "malicious exchange" because it was "to the detriment and harm of science, a joke for the population and becomes a scandal for the world of science ”.

Shortly after the first correspondence between Owen and Huxley in the magazine Athenaeum , the anonymous mocking poem "Monkeyana", signed with "Gorilla", appeared in the satirical magazine Punch in May 1861 . After briefly delving into the Vestiges , Darwin, and some recent archaeological discoveries, the poem mocks the argument between the two. The poem was written by the paleontologist and MP Philip Egerton , a friend of Owens who, however, did not take sides with either side. In 1861, about half a dozen satires appeared in Punch magazine on the debate or those involved. A good year later, another mocking poem by Egerton appeared, again anonymously. The Gorilla's Dilemma is written from the gorilla's perspective. Amazed by the professors, he offers them his own view of the problem of the relationship between apes and humans. He wonders whether the monkey does not often stand above people, because he can bite much harder with his jaw, he does gymnastics better, he makes better faces and, above all, he is able to remain silent. A recently published article summarized the appearance of Owen and Huxley in Cambridge in the form of a duet sung together.

The Anglican clergyman and writer Charles Kingsley wrote in a letter to Charles Darwin in November 1859, expressing his respect for his work On the Origin of Species . As a participant in the BAAS meeting in Cambridge, he witnessed the argument between Owen and Huxley and wrote a short gloss about it for his friends . In a fictional speech, Lord Dundreary thanks the audience in “Section D” for “allowing them to live in the eloquent argument, although no one would have understood what it was actually about and who was right, everyone was very interested in her Hippos [hippopotamus] in their brains. "

The basic elements of this gloss flowed into Kingsley's fairy tale The Water Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby (German title Die Wasserkinder ) and made the "hippocampus" as popular as Alice in Wonderland the dodo two years later . The Water Children appeared as a serialized story in Macmillan's Magazine from August 1862 to March 1863 and was subsequently published in book form. It is one of the most popular children's books of the Victorian Age . Kingsley created the character of Professor Ptthmllnsprts (Put-them-all-in-spirits) for his story, who symbolizes both opponents.

“He had very strange theories about quite a few things. At one point he even got up at the British Association and stated that monkeys, just like humans, have large hippos in their brains. How dreadful to say such a thing, because if so, what would happen to the faith, hope and charity of millions of immortals? … No, my dear little man, always remind yourself that the real, reliable, definitive and very important difference between you and a monkey is that you have a big hippo in your brain and he doesn't have one. And it is therefore a very wrong and dangerous thing to find something in your brain that would dismay anyone. "

The most biting satire was the short play A Report of a Sad Case , published anonymously in 1863 , in which the two street vendors Dick Owen and Tom Huxley sell "old bones, bird skins and innards." They quarrel with each other. When they abuse each other, they are arrested and brought to justice. During the trial, the two continue to accuse each other. Terms like “back horn” and “hippocampus” are shouted. At the end of the trial, the Lord Mayor refuses to condemn her, "as no punishment can correct wrongdoers who are so incorrigible." He advises Owen that instead of being bitter about being compared to a monkey, Owen should not behave like one, but rather like a person. He pointed out to Huxley that he was less interested in the truth and more interested in destroying his rival.

The events of the debate between Owen and Huxley found their way into contemporary reception some time later. In an 1865 drawing, Charles Henry Bennett (1829–1867) parodied various participants in the meetings of the British Association, including Owen and Huxley, who dance a jig in front of mice with skulls and almost strangle themselves. The politician and satirist John Edward Jenkins (1838-1910) mentioned a professor Cruxley in Lord Bantam in 1872 , who is a member of the Royal Society and who gave a lecture at the “Grand Eclectic Symposium and Aesthetic Soiree” on “The Hippocampus Minor and its relation to the Mosaic Cosmogony “(The hippocampus minor and its relationship to the Mosaic cosmogony).

Richard Owen's grandson of the same name published his grandfather's biography in 1894, for which he asked Thomas Henry Huxley for a contribution. The minor hippocampus debate was not mentioned by Huxley in his contribution to Owen's tribute. Owen's grandson also omitted it in his biography.

Modern reception

For a long time, the hippocampus debate was viewed only as part of the dispute between the supporters and opponents of Darwin accompanying the publication of Charles Darwin's work The Origin of Species , and its outcome was presented exclusively from the point of view of "Darwin's Bulldog" Huxley. For example, William Irvine wrote in 1955 in his book Apes, Angels and Victorians: The Story of Darwin, Huxley, and Evolution : “Huxley triumphed in every respect and only gained further fame through his fierce opponents. […] By the time Huxley's Evidence of Man's Place appeared in Nature in 1863, Owen was almost a historical curiosity. "

Owen and his scientific achievements fell into oblivion soon after his death, since he, as Nicolaas Rupke put it in his biography of Richard Owen, was systematically "written out" by Darwin and his followers from Victorian history and the memory of him only through his criticism the Darwinian theory of evolution had been kept alive by natural selection . It was not until the mid-1960s that science historians began to grapple with Owen and his contributions to the development of the evolutionary idea. The scientists Roy M. MacLeod, Dov Ospovat (1947–1980), Adrian Desmond and Nicolaas A. Rupke contributed to Owen's rehabilitation .

In more recent studies, the hippocampal debate between Owen and Huxley was examined against the background of the scientific and philosophical views as well as the personal and social position of the two adversaries. Nicolaas A. Rupke pointed out in 1994 that Owen had relativized his initially absolute statement about the existence of the three brain peculiarities and placed their expression at the center of his replies, while Huxley always referred to Owen's original statement. In 1994, Christopher E. Cosans examined Huxley's motives for narrowing the differences between humans and apes while at the same time widening the races of human beings with his reasoning, and assumed that Huxley had racist motives. CUM Smitha used the 1997 hippocampal debate as a case study to show how rapidly changing social factors of the Victorian era helped Huxley and Darwin's views on the place of humans in nature eventually prevailed. In 2007 Thomas Gondermann pointed out that the debate was not only important for the implementation of Darwin's theory of evolution, but also for the development of anthropology .

proof

literature

- Per Andersen: The Hippocampus Book . Oxford University Press, Oxford [et al.], 2007. ISBN 978-0-19-510027-3 .

- WF Bynum: Charles Lyell's Antiquity of Man and its critics . In: Journal of the History of Biology . Volume 17, No. 2, Springer Netherlands, 1984, pp. 153-187, doi : 10.1007 / BF00143731 .

- Christopher E. Cosans: Anatomy, Metaphysics, and Values: The Ape Brain Debate Reconsidered . In: Biology and Philosophy . Volume 9, No. 2, 1994, pp. 129-165, doi : 10.1007 / BF00857930 .

- Christopher E. Cosans: Owen's Ape and Darwin's Bulldog . Beyond Darwinism and Creationism. Indiana University Press, Bloomington [et al. a.] 2009. ISBN 978-0-253-22051-6 .

- Adrian Desmond: Huxley: From Devil's Disciple to Evolution's High Priest . Perseus Books, Cambridge, MA 1999, ISBN 978-0-7382-0140-5 .

- Adrian Desmond, James Moore: Darwin (Original title: Darwin translated by Brigitte Stein). 2nd edition List, Munich / Leipzig 1993 (German first edition 1991), ISBN 3-471-77338-X .

- Charles G. Gross: Hippocampus minor and man's place in nature: A case study in the social construction of neuroanatomy . In: Hippocampus . Volume 3, No. 4, pp. 403-415, 1993, doi : 10.1002 / hipo.450030403 .

- Charles G. Gross: Huxley versus Owen: the hippocampus minor and evolution . In: Trends in Neurosciences . Volume 16. No. 12, pp. 493-498, 1993, doi : 10.1016 / 0166-2236 (93) 90190-W .

- Charles G. Gross: Brain, vision, memory: tales in the history of neuroscience . MIT Press, 1999, pp. 137-181, ISBN 0-262-57135-8 .

- Thomas Gondermann: "Hippocampus minor" Huxley versus Owen . In: Evolution and Race: Theoretical and Institutional Change in Victorian Anthropology . Transcript, Bielefeld 2007. ISBN 978-3-89942-663-2 , pp. 105-117.

- Leonard Huxley (Ed.): Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley . 3 volumes, 2nd edition, Macmillan and Co., London 1908, Volume 1, pp. 275-301.

- William Irvine: Human Skeletons in Geological Closets . In: Apes, Angels and Victorians: The Story of Darwin, Huxley, and Evolution . McGraw-Hill, New York / London / Toronto, 1955, pp. 135-150.

- Roy M. MacLeod: Evolutionism and Richard Owen, 1830–1868: An Episode in Darwin's Century . In: Isis . Vol 56, No. 3, Chicago 1965, pp. 259-280, JSTOR 228102 .

- Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen: Biology without Darwin . Revised edition, University Of Chicago Press 2009, ISBN 978-0-226-73177-3 , pp. 182-253.

- CUM Smitha: Worlds in Collision: Owen and Huxley on the Brain . In: Science in Context . Volume 10, Cambridge University Press 1997, pp. 343-365, doi : 10.1017 / S0269889700002672 .

- Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . In: Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences Volume 51, No. 2, 1996, pp. 184-207, doi : 10.1093 / jhmas / 51.2.184 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Karl-Josef Moll: Anatomy: Short textbook for the catalog of objects 1 . Section 9.9.1 Lateral ventricle . Elsevier, Urban & Fischer Verlag, 2005, ISBN 978-3-437-41743-6 .

- ^ Charles G. Gross: Brain, vision, memory: tales in the history of neuroscience . P. 143.

- ^ Wilfrid Blunt: The ark in the park: The Zoo in the nineteenth century . Tryon Gallery, Hamilton 1976, pp. 38-40.

- ^ Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . Pp. 186-187.

- ^ Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . P. 188.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 188.

- ^ A b Thomas Gondermann: Evolution and Race: Theoretical and Institutional Change in Victorian Anthropology . P. 108.

- ↑ Christopher Cosans: Anatomy, Metaphysics, and Values: The Ape Brain Debate Reconsidered pp. 141-144.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . Pp. 186-187

- ^ Charles Darwin to Joseph Dalton Hooker , July 5, 1857, Letter 2117 in The Darwin Correspondence Project (accessed August 14, 2009).

- ^ Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . P. 191.

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley: The Principles of Biology . Royal Institution, January 19 - March 23, 1858.

- ^ Adrian Desmond: Huxley: From Devil's Disciple to Evolution's High Priest . Pp. 240-241.

- ^ Adrian Desmond, James Moore: Darwin . P. 553.

- ^ Leonard Huxley (Ed.): Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley . 3 volumes. 2nd edition, Macmillan and Co., London 1908, Volume 1, pp. 260-261.

- ^ Adrian Desmond, James Moore: Darwin . P. 513.

- ^ Adrian Desmond: Huxley: From Devil's Disciple to Evolution's High Priest . P. 276

- ^ Leonard Huxley (Ed.): Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley . 3 volumes. 2nd edition, Macmillan and Co., London 1908, Volume 1, p. 261.

- ^ [Anonymous]: Science: British Association . In: The Athenaeum . No. 1706, July 7, 1860. p. 26.

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley: On the Zoological Relations of Man with the Lower Animals . In: Natural History Review . New series, Volume 1, January 1861, p. 67.

- ↑ Christopher E. Cosans: Anatomy, Metaphysics, and Values: The Ape Brain Debate Reconsidered pp. 147-149.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 195.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . Pp. 195-196.

- ^ Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . P. 195.

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley: On the Zoological Relations of Man with the Lower Animals . In: Natural History Review . New series, Volume 1, January 1861, p. 75.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 235.

- ^ Colin Groves: A history of gorilla taxonomy . In: Andrea Taylor, Michele Goldsmith (Eds.): Gorilla Biology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective . Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-521-79281-9 .

- ^ Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . P. 189.

- ^ Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . Pp. 190-191.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 185.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . Pp. 235-243.

- ^ Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . P. 198.

- ^ Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . P. 196.

- ^ Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . P. 197.

- ^ Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . P. 200.

- ^ A b Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . P. 201.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 201

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 202.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . Pp. 202-203.

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley to Charles Darwin, October 9, 1862, Letter 3755 in The Darwin Correspondence Project (accessed September 23, 2009).

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . Pp. 203-204.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 209.

- ^ Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . Pp. 202-204.

- ^ Joseph Dalton Hooker to Charles Darwin, February 23, 1863, Letter 4007 in The Darwin Correspondence Project (accessed September 20, 2009).

- ^ Charles Darwin to Thomas Henry Huxley, February 26, 1863, Letter 4013 in The Darwin Correspondence Project (accessed September 20, 2009).

- ^ WF Bynum: Charles Lyell's Antiquity of Man and its critics . P. 156.

- ^ WF Bynum: Charles Lyell's Antiquity of Man and its critics . Pp. 154-159.

- ^ Leonard G. Wilson: The Gorilla and the Question of Human Origins: The Brain Controversy . P. 206.

- ^ A b Charles G. Gross: Huxley versus Owen: the hippocampus minor and evolution . P. 497.

- ^ Roy M. MacLeod: Evolutionism and Richard Owen, 1830–1868: An Episode in Darwin's Century . Pp. 277-278.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 217.

- ^ Charles G. Gross: Hippocampus minor and man's place in nature: A case study in the social construction of neuroanatomy . P. 411.

- ^ Charles Kingsley to Charles Darwin, Nov. 18, 1859, Letter 2534 in The Darwin Correspondence Project, (accessed September 5, 2009).

- ^ A b Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 221.

- ^ A b Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 222.

- ^ Charles Kingsley's The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby . Chapter 4 In: Macmillan's Magazine . Volume 7, Nov. 1862, p. 8. Online

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 224.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 225.

- ^ William Irvine: Apes, Angels and Victorians: The Story of Darwin, Huxley, and Evolution . McGraw-Hill, New York London Toronto, 1955, p. 139.

- ^ Nicolaas A. Rupke: Richard Owen. Biology without Darwin . P. 3.

Primary sources

- ^ Richard Owen: On the Anatomy of the Orangutan (Simia satyrus, L.) . In: Proceedings of the Committee of Science and Correspondence of the Zoological Society of London . Volume 1, London 1830, pp. 4-5, 8-10, 28-29, 67-72. On-line

- ^ Richard Owen: On the Osteology of the Chimpanzee and Orang Utan . In: Transactions of the Zoological Society of London . Volume 1, London 1835, pp. 343-379. On-line

- ^ Richard Owen: On the Characters, Principles of Division, and Primary Groups of the Class Mammalia . In: Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London . Volume 2, London 1858, pp. 1-37. On-line

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley: On Species and Races, and Their Origin . In: Medical Circular . No. 401, March 7, 1860, pp. 149-150. On-line

- ^ Charles Daubeny: Remarks on the Final Causes of the Sexuality of Plants, with particular reference to Mr. Darwin's Work 'On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection' . In: Report of the thirthieth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science held at Oxford in June and July 1860 . John Murray, London 1861, pp. 109-110. On-line

- ↑ [Anonymous]: The Athenaeum . No. 1706, July 7, 1860, pp. 25-26.

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley: On the Zoological Relations of Man with the Lower Animals . In: Natural History Review . Neue Serie, Volume 1, January 1861, pp. 67-84. On-line

- ^ TS Savage and J. Wyman: Notice of the external characters and habits of Troglodytes gorilla, a new species of orang from the Gaboon River; Osteology of the same . In: Boston Journal of Natural History . Volume 5, 1847, pp. 417-442.

- ^ Richard Owen: On a New Species of Chimpanzee . In: Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London . Volume 16, 1848, pp. 27-35. On-line

- ↑ Richard Owen: Osteological contributions to the natural history of the chimpanzees (Troglodytes, Geoffroy), including the descriptions of the skull of a large species (Troglodytes Gorilla, Savage) discovered by Thomas S. Savage, MD in the Gaboon Country, West Africa . In: Transactions of the Zoological Society of London . Volume 3, London 1849, pp. 381-422. On-line

- ↑ Richard Owen: Osteological contributions to the natural history of the Chimpanzees (Troglodytes) and Orang (Pithecus) No. IV. Description of the cranium of an adult male Gorilla, from the River Danger, west coast of Africa, indicative of a variety of the great Chimpanzee (Troglodytes gorilla), with remarks on the capacity of the cranium and other characters shown by the skull , in the Orangs, Chimpanzees and different varieties of the human race . In: Transactions of the Zoological Society of London . Volume 4, [1862]. Pp. 89-115.

- ↑ Richard Owen: Osteological contributions to the natural history of the Chimpanzees (Troglodytes) and Orang (Pithecus) No. V. Comparison of the lower jaw and vertebral column of the Troglodytes gorilla, Troglodytes niger, Pithecus satyrus and different varieties of the human race . In: Transactions of the Zoological Society of London . Volume 4, [1862], pp. 75-88.

- ↑ Richard Owen: On the Gorilla . In: Proceedings of the Royal Institution . Volume 3, London 1858-1862, pp. 10-30. On-line

- ^ Paul Belloni Du Chaillu: Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa . J. Murray, London 1861. Online

- ↑ Richard Owen: The Gorilla and the Negro . In: The Athenaeum . No. 1743, March 23, 1861, pp. 395-396. On-line

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley: Man and the Apes . In: The Athenaeum . No. 1744, March 30, 1861, p. 433. Online

- ↑ Richard Owen: The Gorilla and the Negro . In: The Athenaeum . No. 1745, April 6, 1861, p. 467.

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley: Man and the Apes . In: The Athenaeum . No. 1746, April 13, 1861, p. 498.

- ^ George Rolleston: On the Affinities of the Brain of the Orang Utang . In: Natural History Review . Volume 1, April 1861, pp. 201-217. On-line

- ^ John Marshall: On the Brain of a Young Chimpanzee . In: Natural History Review . Volume 1, July 1861, pp. 296-315. On-line

- ^ Richard Owen: On the cerebral characters of man and the ape . In: Annals and Magazine of Natural History . 3rd Series, Volume 7, London 1861, pp. 456-458. On-line

- ^ Jacobus Schroeder van der Kolk, Willem Vrolik: Note sur l'encephale de l'orang utang . In: Natural History Review . Volume 2, London 1862, pp. 111-117.

- ^ William Henry Flower: On the Posterior Lobes of the Cerebrum of the Quadrumana . In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London . Volume 152, 1862, pp. 185-201. On-line

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley: On the Brain of Ateles Paniscus . In: Proceedings of the Zoological Society . London 1861, pp. 493-508. Full text

- ^ Richard Owen: On the characters of the Aye-aye, as a test of the Lamarckian and Darwinian hypothesis of the transmutation and origin of species . In: Report of the thirty-second Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science held at Cambridge in October 1862 . John Murray, London 1863, pp. 114-116. On-line

- ^ Richard Owen: On the zoological significance of the cerebral and pedial characters of man . In: Report of the thirty-second Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science held at Cambridge in October 1862 . John Murray, London 1863, pp. 116-118. On-line

- ↑ [Anonymous]: The Athenaeum . No. 1824, October 11, 1862, p. 468.

- ^ Richard Owen: On the Zoological Significance of the Brain and Limb Characters of the Gorilla, as Contrasted with Those of Man . In: Medical Times and Gazette . No. 2, October 11, 1862, pp. 373-374. On-line

- ↑ George Rolleston: On the Distinctive Characters of the Brain in Man and in the Anthropomorphous Apes . In: Medical Times and Gazette . No. 2, October 18, 1862, pp. 418-420. On-line

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley: The Brain of Man and Apes . In: Medical Times and Gazette . No. 2, October 25, 1862, p. 449. Online

- ^ Charles Lyell: The age of the human race on earth and the origin of the species by modification: together with a description of the Ice Age in Europe and America Theodor Thomas, Leipzig 1864. Online

- ^ Richard Owen: Ape-origin of Man as tested by the brain . In: The Athenaeum . No. 1843, February 21, 1863, pp. 262-263.

- ↑ George Rolleston: Ape-origin of Man (Feb. 24, 1863) . In: The Athenaeum . No. 1844, February 28, 1863, p. 297.

- ^ Charles Lyell: The brain in Man and the Ape (Feb. 26, 1863) . In: The Athenaeum . No. 1845, March 7, 1863, pp. 331-332.

- ↑ Minor hippocampus . In: A dictionary of Science, Literature and Art, ed. By WT Brande assisted by J. Cauvin. ed. by WT Brande and GW Cox . 3 volumes, Longmans, Green & Co., London 1866, Volume 2, p. 127, online

- ^ Richard Owen: On the Anatomy of Vertebrates . Volume 2, Green and Co., London 1866, p. 273, online

- ↑ [Anonymous]: Men Or Monkeys? In: British Medical Journal . Volume 2, No. 94, October 18, 1862, pp. 419-420, doi : 10.1136 / bmj.2.94.419 .

- ↑ [Philip Egerton]: Monkeyana . In: Punch, or the London Charivari . Vol. 40, No. 1036, May 18, 1861, p. 206. Online

- ^ [Philip Egerton]: The Gorilla's Dilemma (to Professor Owen & Huxley) . In: Punch, or the London Charivari . Volume 43, No. 1110, October 18, 1862, p. 164. Online

- ^ [Anonymous]: The Cambridge Duet . In Punch, or the London Charivari . Volume 43, No. 1109, October 1862, p. 155. Online

- ^ Charles Kingsley: Speech of Lord Dundreary in Section D, on Friday Last, On the Great Hippocampus Question . On-line

- ↑ [George Pycroft]: A Report of a Sad Case, Recently tried before the Lord Mayor, Owen versus Huxley, In which will be found fully given the Merits of the great Recent Bone Case . London 1863. Online

- ^ Charles Henry Bennett: The British Association . In: Punch, or the London Charivari . Volume 49, No. 1263, September 23, 1865, pp. 113-114.

- ↑ [John Edward Jenkins]: Lord Bantam . 2 volumes, Strahan & Co., London 1872. Volume 2, p. 158. Online

- ^ Thomas Henry Huxley: Owen's Position in the History of Anatomical Science . In: Richard Owen (Ed.): The Life of Richard Owen . Volume 2, London 1894, pp. 273-332. On-line

Web links

- Charles Blinderman, David Joyce Bobbing Angels: Human Evolution . In: The Huxley File