Iban (ethnic group)

| Iban | |

|---|---|

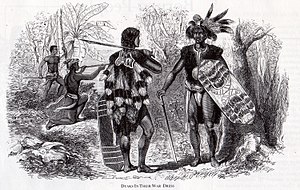

Iban warriors in the 19th century |

|

| Settlement area: | Northwest Borneo |

| Number: | Over 700,000 |

| Language: | Iban |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

The Iban , also called Sea Dayak , are an indigenous ethnic group from the island of Borneo . They are counted as part of the Dayak group . The home region of the Iban is the north-west of Borneo, especially the Malaysian state of Sarawak . There they make up around 30% of the population with around 680,000 members (as of 2006) and represent the largest ethnic group. However, tens of thousands of Iban also live in the neighboring Indonesian province of Kalimantan Barat and in Brunei .

The traditional characteristics of the Iban culture include life in longhouses and slash- and- burn farming , but this way of life has increasingly faded into the background since the middle of the 20th century. During the colonial era, the Iban were known for headhunting and piracy , which led to violent clashes with European colonial powers , particularly the British adventurer James Brooke, known as the white Raja, and his successors. They speak the Iban language named after them .

Surname

The term "Iban" was originally a foreign name that was used by other ethnic groups and adopted by the European colonial powers. In western usage, the term was established by the British colonial official and researcher Charles Hose at the beginning of the 20th century . It was not until the 1950s that the Iban itself adopted it as its own name. The word origin of the term is unclear.

The synonymous term "Sea Dayak", which has since been felt to be out of date, goes back to James Brooke . When he became Raja of Sarawak in 1842 , he distinguished the indigenous population of his empire into Land Dayak (the Bidayuh ) and Sea Dayak (the Iban). He chose Sea Dayak because the Iban often attacked in boats from the sea during their raids. However, since they lived away from these raids in the interior of Borneo and had hardly any contact with the sea, the term is quite misleading, as it falsely suggests a sea-bound way of life. Sea Dayak has long been considered an alternative to Iban, and it was only since 2002 that the Sarawak government no longer used the terms “Sea Dayak” and “Land Dayak” in official documents. In the Malaysian constitution, which has existed since 1963, these terms are still used today.

Originally, the Iban did not have a name for their ethnic group as a whole, as they did not see themselves as a unified, cohesive people. Contacts between Iban communities in distant regions were often warlike rather than peaceful. The common language, culture and way of life were not seen as a solidarity-creating, connecting feature. Instead of an ethnic name, it was therefore common to use a geographical name, for example by referring to oneself as a resident of one's home river ( e.g. Kami Saribas , roughly “We from the Saribas River”).

Culture

Shifting cultivation

A central element in traditional Iban life was shifting agriculture , where rice was the main food that was cultivated using slash and burn . Since a cultivation area gained in this way can only be used a few times, sometimes even for only one harvest period, an Iban community consumed all suitable areas in the vicinity of their longhouse over the course of about a decade and then moved on. Since untouched primary forest is also much more productive than secondary forest with this type of farming , the Iban were forced to regularly develop new land. In this way, their settlement area shifted from southwest Borneo over several centuries further northwards, into today's Sarawak.

In addition to rice, the Iban also grew smaller quantities of other crops and used natural food sources such as wild fruits. The need for meat was met with hunting, and the wild boar in particular was a popular prey animal. The blowpipe was used as a weapon , the arrows of which were soaked in the highly toxic sap of the Upas tree ( Antiaris toxicaria ).

Longhouses

Like many other indigenous peoples of Borneo, the Iban traditionally live in long houses . A single long house houses the entire village community and contains all living, working and storage space. Over 50 families can live in a long house, the length of the house can be several hundred meters. Traditional wooden longhouses were built on stilts on the banks of a river. The fast growing and easy to process bamboo was a popular building material. It had a shelf life of around 10 years.

Each nave is divided into a public and a private area. The internal structure of a long house follows a uniform scheme that can be found in all long houses. One half of the nave is open to the public, while the other half contains the private, not generally accessible private rooms of the individual families. The public area in the front half runs along the entire length of the nave and is not interrupted by walls or other boundaries. In terms of architecture, it is ultimately a gallery . The private living rooms are lined up along this gallery in the rear part of the nave. The internal structure of a long house is therefore very similar to western terraced houses or the typical construction of American motels .

In the case of older long houses, an uncovered, balcony-like terrace runs along the front, public half, which is used, for example, to dry the threshed rice after the harvest . In modern longhouses that are not built using pile construction, this terrace is occasionally missing today. The same applies to the attic, which every longhouse traditionally owned, since rice and other food could be stored there protected from vermin and moisture.

Although it is a single, connected building, a longhouse is not a common property of its residents. Each family has its own section and maintains it according to its own possibilities and means. Each family decides for themselves what material and with what effort they will build their part of the nave. The size of the individual sections also varies depending on the wealth of the family. Furthermore, a family can decide at any time to move out of their longhouse. Therefore, it can happen that a gap arises in the middle of the longhouse when a family leaves the community and takes their part of the longhouse with them.

Belief

The traditional Iban belief is shaped by polytheistic and animistic ideas. The highest god is Singalang Burong , who is worshiped as the god of war and the god of headhunting. The harvest goddess Pulang Gana is also important .

Birdsong have a special meaning . Birds are considered to be the conveyors and carriers of messages from supernatural beings and gods, so their song requires careful observation and interpretation. The exact meaning of a bird call depends largely on the interpretation by the Iban themselves, so it is important which bird is heard at which time of day, from which direction and at what distance. Depending on the circumstances, the same call can therefore both predict happiness or indicate the approval of the gods and also be a warning of impending doom. Other natural phenomena such as thunderstorms, storms or the sighting of rare animals are sometimes interpreted as omen.

In addition to the gods, the Iban religion also knows other supernatural beings, which are collectively referred to as Antu . These include nature spirits, deceased ancestors and other mythological beings who, like the gods, can intervene in earthly life and therefore have to be good-natured with offerings and rituals. Certain places such as clearings, caves or hills are considered to be the abode of supernatural beings, and even relatively everyday things such as stones or trees are assigned a conscious soul. Powers are also attributed to the skulls captured during headhunting. This animistic view that objects are animated led to what some European observers found odd. When the Iban first came into contact with modern technology such as hunting rifles and chainsaws via the Europeans, it was completely natural to thank these objects for their functioning before and after use with rituals and offerings.

The Iban made representations of the spirits in the form of wood carvings, which could be of various sizes and represent a wide variety of motifs. This ranged from small, hardly hand-sized figures of people or animals to sculptures of the rhinoceros bird ( iba: Kenyalang ) over a meter long for special religious festivals.

Christian missionaries were only able to reach the population of Sarawak very late, at the beginning of the 20th century, because the Brookes' stated aim was to enable them to live a largely undisturbed life without European cultural pressure.

"We stuff natives with a lot of subjects they don't require to know and try to teach them to become like ourselves, treating them as though they had not one original thought in their possession."

In 1960, of the approximately 240,000 Iban in Sarawak, 210,718 still professed their original beliefs, and only 26,608 professed to Christianity and 415 to Islam . In the meantime, however, the majority have converted to Christianity, in 2005 it was around 70% of all Malaysian Iban.

Headhunting

The headhunting as the ritual capture and home Bring the skull called my enemies, was an insular in Borneo and throughout Southeast Asia spread to many ethnic groups practice. The Iban have often been described by contemporary European observers as particularly avid headhunters, as they believed that headhunting was often the primary purpose and not a by-product of pirate raids. In addition to the general gain in prestige for a successful headhunter, bringing home fresh skulls was primarily of religious importance, for example for the rituals that were held when building a new nave, when the village head was married or to end the period of mourning after the death of a longhouse inhabitant , new trophy skulls desired. Another motive for headhunting was retaliation when a community was itself a victim of headhunting. Later, in the course of their activity as pirates, the Iban went headhunting for no specific reason. The manner in which the head was looted was secondary, defeating an enemy warrior in a duel was not considered "more honorable" than killing a woman or a child or beheading a corpse.

The end of ritual headhunting was brought about by James Brooke and his nephew and successor Charles Brooke, who violently fought headhunting and effectively abolished it over the course of several decades. There were only a few head-hunts afterwards, for example in the Second World War when fighting Japanese soldiers or in the 1970s, when 15 Koreans who were helping to build a liquid gas terminal in Sarawak were murdered by Iban and their heads were stolen.

piracy

The Iban enterprises, later referred to as piracy by the colonial powers , began in the early 19th century. Although the Iban had been headhunting and robbery trips into nearby river systems for at least the 16th century, these were locally limited and usually had the purpose of driving out the local tribes in order to claim this land themselves. This was always the occasion for the ritually extremely important headhunting.

The resulting piracy of the 19th century did not come from all Iban, but exclusively from the Iban communities who had given up the semi-nomadic way of life at the end of the 18th century and had settled down. As a result, there was no longer any way of combining land gain with headhunting. In order to keep capturing new heads on a regular basis, they were therefore forced to go on robbery trips to distant areas. In addition, these sedentary Iban had established trade contacts with Malays living on the coast . These were independent of the Sultan of Brunei . They initially allied themselves with the Iban in order to take action against rival competitors or to secure their independence. In addition to some of the booty and prisoners, the Iban were given the right to keep all of the captured heads. Recognizing the fighting strength of the Iban, the Malays later went on to organize robbery trips on a large scale, in which villages and settlements along the north-west coast of Borneo as well as merchant ships caught close to the coast were ambushed and looted. In the course of time the Iban went on a robbery on their own. Early British observers put forward the thesis that it was only through these Malays that the previously innocent and peaceful Iban were seduced into piracy and headhunting. This thesis has now been refuted, since both the tradition of headhunting and this type of warfare have been part of the Iban tradition since at least the 16th century. Only the size and scope of the ventures increased in the 19th century due to the influence of the Malays.

An Iban pirate fleet could consist of several thousand warriors who went to sea in oar-driven boats that carried up to 100 men. The area of their raids stretched roughly from the mouth of the Rejang in the north to the mouth of the Kapuas in the south.

The Iban never pursued deep sea piracy, but occasionally individual Iban hired as mercenaries with other pirate peoples such as the Illanun . However, there were also warlike contacts with these peoples, for example when the Iban themselves became the target of piracy. Fleets of the Illanun or other pirate peoples such as the Bajau have tried several times to penetrate the home rivers of the Iban and plunder their longhouses.

Art and body jewelry

A traditional art form of the Iban was the art of weaving, in which they made carpets with dyed fabrics in typical patterns called Pua Kumbu . The art of weaving was the domain of women.

Like numerous other ethnic groups in Borneo, the Iban also have a tradition of tattooing (iba: Pantang ). Traditionally, this was done mainly by men, but also partly by women, and included tattoos on the arms, legs, back, shoulders and neck. Motifs were abstract shapes and patterns, with depictions of animals and floral patterns as recurring motifs. The tattoo of the neck was considered a particularly honorable test of courage. It was also a custom in some Iban communities that only successful headhunters were allowed to have their hands tattooed. Sometimes the entire back of the hand was tattooed after the first captured head, sometimes a single phalanx for each head. The dye used was soot mixed with water , which was punched under the skin using a sharp bone splinter and a stick as a hammer. While in the past every male Iban was usually tattooed, these are less common these days. Even today, many men can still be tattooed, but western or other motifs are often chosen, and tattoos are no longer carried out in the nave using traditional methods, but in a modern tattoo studio in a larger city.

In earlier times, the tradition, also carried out by both sexes, of stretching the earlobes with heavy weights until after a few years they could be several centimeters long and almost reach the shoulders was also widespread .

history

Pre-colonial period

Since the Iban had no script, their early history had to be reconstructed almost exclusively from their own oral traditions. This story can be reproduced with sufficient accuracy from the 16th century, when they settled the south of what is now Sarawak. The traditions from the time before are only preserved in very fragments and are also heavily distorted by mythological enrichment.

According to the current state of research, the ancestors of the Iban settled in the first half of the second millennium AD, probably from Sumatra, in the area around the mouth of the Kapuas River in the vicinity of today's Indonesian city of Pontianak , on the southwest coast of Borneo. From there, over the centuries, a gradual migration took place into the headwaters of this river, which is located directly on today's Indonesian-Malaysian border. From the middle of the 16th century they reached the area of today's Sarawak, which was formally claimed by the Sultanate of Brunei. It is assumed, however, that this was not known to the Iban and that Brunei also had no closer interest in the indigenous peoples living inland at that time. The annual tribute payments that the Sultan demanded from his subjects concerned only the Malays living on the coast.

The constant expansion of the Iban can be traced back to shifting cultivation , which forced every longhouse community to move on about every ten years in order to be able to gain new rice cultivation areas from the primary jungle . The Iban were never a cohesive, centrally controlled unit; instead, each longhouse community decided for itself when and where to migrate. Contacts or alliances only existed between longhouses that were close together, but never over long distances. As they spread, the Iban encountered already resident ethnic groups from Borneo from the start. These were usually less numerous and often nomadic hunter-gatherers . Some of them were forcibly expelled and even exterminated, but some were also assimilated peacefully by adopting the Iban culture and way of life. This constant expansion of the Iban settlement area continued continuously, in the east of the later Sarawak the Iban finally met the Bidayuh , while in the north lay the settlement areas of the Kayan , with which they fought numerous violent conflicts over the supremacy of river systems. From the 18th century, however, some longhouse communities gave up the semi-nomadic way of life. Instead, they remained in the central core area of the Iban, where there was only a little primary jungle, but where, due to the migration of other longhouse communities, sufficiently large areas of secondary jungle were available, which made it unnecessary to move on. Instead, such a longhouse community simply claimed such a large area that even the less productive secondary jungle could be given enough time to regenerate after a harvest period. This made permanent sedentarism possible. In return, these Iban tribes began to undertake predatory war journeys to distant areas. Malay coastal settlements, Chinese merchant ships and foreign Dayak peoples were attacked as well as distant Iban settlements. The attacks on the Malays and the Chinese were later referred to as piracy and led to massive counter-actions by European colonialists from the middle of the 19th century, the attacks on other Dayak founded intertribal wars between the various Iban factions and between the Iban and other Dayak peoples. This phase of settling in the heartland on the one hand and the continuing expansion in the peripheral areas on the other hand initially took place without external interference until the Briton James Brooke landed in Sarawak for the first time in 1839 and became the local ruler a few years later.

The Brooke family

James Brooke was an adventurer from England and landed for the first time on the coast of Borneo, in the city of Kuching , in 1839 . Since he helped the Sultan of Brunei to end a local rebellion of the Dayak tribe of the Bidayuh , he was enfeoffed by the Sultan in 1842 with a piece of land around the city of Kuching and raised to the title of Raja . This fiefdom was named after the main river that flows here, the Sarawak . He was known as the first of a total of three white Rajas from Sarawak. His successor from 1868 was his nephew Charles Brooke , whose son Charles Vyner Brooke in turn led the empire from 1917 to 1946. In the course of time, the first two Brookes succeeded in getting more and more land from the Sultan or annexing them until Sarawak had finally reached its present size.

The Iban's activities as pirates and the intertribal wars were at their peak at this time, as the Sultan of Brunei, although nominally claiming this part of Borneo, had no real influence over the local Dayak peoples. James Brooke, however, saw this as a threat to the economy of his young empire, as it deterred merchant ships and threatened workers in the tin mines and on the plantations. He therefore banned headhunting and punished those Iban who disobeyed his orders. He also forbade them to move on independently, as this mostly went hand in hand with fighting and driving out the long-established population. Although this was not considered piracy, as it only affected the Dayak ethnic groups among themselves, Brooke saw it as a potential source of unrest for larger conflicts. Since he did not have an army of his own, he initially received support from the British Royal Navy , the Royal Marines and the fleet of the British East India Company .

But since Sarawak was not a colony of the British Crown but an independent empire, doubts grew in England about maintaining this support. Many viewed Sarawak as a private adventure for James Brooke and saw no reason to support him with ships and soldiers. In addition, there was a certain romantic basic attitude towards the indigenous peoples in the colonies in Victorian England at this time . They were seen as innocent, primitive people who should not be punished for their traditional way of life for reasons of power politics. These critics of James Brooke finally took the naval battle of Beting Maru on July 31, 1849 as an opportunity to set up a committee of inquiry with the aim of prohibiting Brooke from any support from the Royal Navy. At the Battle of Beting Maru, several British warships, together with allied Iban, captured and surrounded a large dugout fleet of the pirate Iban on the open sea. The British ships were seaworthy sailing and steam-powered warships and equipped with the most modern weapons in the world at the time, against which the Iban, who sailed in dugouts and mostly armed with blowguns, sabers and spears, had no chance. It is estimated that 2,140 to 3,700 Iban pirates were involved, of whom between 500 and 800 were killed. The commission of inquiry came to the conclusion that the Iban had indeed been pirates and that James Brooke had acted legitimately as the feudal man of the Sultan of Brunei, but from 1854 the Royal Navy almost completely stopped its military aid to Brooke due to political pressure.

As a result of these events, he had to rely almost entirely on local warriors to get his way. To this end, he had concluded alliances with those Iban tribes who saw the Iban from the heartland as enemies, for example because they had already become the target of piracy. For these Iban communities, the alliance with the Raja offered the opportunity to go headhunting legally and without fear of punishment, because Brooke allowed the tribes allied with him to keep the captured skulls of the enemy Iban warriors as trophies.

Overall, the first two Rajas managed to end piracy, headhunting, intertribal warfare and the uncontrolled expansion of the Iban through lengthy and numerous military operations and the construction of military forts in strategically important places in the country. They did not change anything about their other way of life, so that the traditional way of life in long houses and as self-sufficient rice farmers could be maintained by all Iban.

Second World War

The era of the White Rajas of Sarawak ended in 1941 with the Japanese invasion of Borneo . The Sarawak Rangers , a largely Iban paramilitary unit, was part of the British Defense Forces of Borneo. The information about their strength varies between 400 and 1,515 men. The unit was disbanded on December 26, 1941, when the British troops gave up Sarawak after losing battles and withdrew to the Dutch part of Borneo. Charles Vyner Brooke , the third and last white Raja, had to flee into exile in Australia. Since the interest of the Japanese was mainly concentrated in the cities and paid little attention to the people living inland, the Iban were initially able to continue their traditional life, even if it occasionally happened that they were obliged to do forced labor or the Japanese demanded their food supplies.

In 1945 the Allied Intelligence Bureau started Operation Semut , during which several British commandos jumped parachute over Borneo to make contact with the indigenous headhunter peoples and to persuade them to resist the Japanese. This should serve as preparation for the planned reconquest of Borneo by the Australian Army . Under the influence of the commandos, the Iban and other indigenous groups of Sarawak began a guerrilla war against the Japanese, as a result of which, according to current estimates, up to 1,500 Japanese were killed.

Since 1945

When Charles Vyner Brooke returned to Sarawak after the end of World War II, he decided to give it to the British Kingdom as a colony. In 1963 it became part of the newly established state of Malaysia . In contrast to the Brooke rule, where the locals (apart from the ban on headhunting) were given a life as undisturbed as possible without external influence, these ethnic groups were now increasingly involved in the modernization process of Malaysia. So the Iban came more into contact with school education and modern technology, and the urbanization of the young Iban began increasingly. In addition, more and more Christian missionaries from Europe came to Borneo to win the population for Christianity. However, these modernization efforts initially only reached those Iban whose longhouses were near the coast or near the larger cities of Sarawak, which is why parts of the Iban who live far inland still live as rice farmers and with traditional animistic beliefs to this day. Nevertheless, in the decades after the Second World War, the Iban's skills as jungle fighters were in demand, so the Sarawak Rangers were re-established in 1953 and the Iban recruited there both in the fight against communist guerrillas from 1948 to 1960 and during the Konfrontasi , a conflict between Malaysia and Indonesia from 1963 to 1966, being recruited as trackers and jungle guides for British, New Zealand and Australian soldiers. The Sarawak Rangers were integrated into the Malaysian Army under the name Royal Rangers Regiment when it was founded, and to this day they are largely recruited from members of the Iban and other indigenous peoples of East Malaysia. The Royal Rangers' motto is also written in Iban and reads Agi idup, agi ngelaban ( Eng . "Still alive, still fighting", or more freely: fight to the death).

Young Iban today mostly live in larger cities and have access to schooling, some of them already in the second or third generation. The traditional way of life in the long house with rice cultivation for self-sufficiency is practiced today only by a minority of the Iban. Many longhouses are only inhabited by the old and are therefore increasingly losing inhabitants. Younger Iban from the cities only return to the longhouse on public holidays, vacations and other special occasions. Since the Iban were able to register the land they cultivated with rice in the past as their property when the state of Malaysia was founded, many of the older longhouses still have relatively large areas of land today. Where rice is no longer grown, these areas are often leased as plantations for food or cash crops such as palm oil , rubber or pepper.

In Malaysia, according to Article 161A of the Malaysian Constitution, the Iban are one of a total of 21 ethnic groups who are considered natives of Sarawak and can therefore benefit from the advantages of the legal Bumiputra status according to the current legal definition . Although the Iban language is still the first language of most young Iban, learning Malay is compulsory for school attendance. Based on the old culture and religion, the Gawai Dayak festival is celebrated on June 1st and 2nd every year , which is an official holiday in Malaysia. For Gawai Dayak, the Iban usually return to their native longhouse and spend several days there, playing traditional music, wearing clothes and drinking alcoholic beverages made from rice. Critical voices, however, complain that the Iban and their culture as well as that of the other indigenous peoples are marginalized by the politically and socially dominant Malays . So 33 Iban longhouse communities were forcibly relocated in the early 1980s as a whole, in order for the completed in 1985 Batang Ai - hydropower plant to make room. The settlement area of the relocated longhouses was flooded by a dam. The Iban concerned complained in retrospect that the promised compensation payments were made very late and in a lower amount than promised. A cultural loss was also lamented as the flooded land had been inhabited by Iban for generations. In 2003, the Malaysian Interior Ministry briefly banned the Iban version of the Bible , which had been used for 15 years before. The reason was the translation of the word "God" with Allah Tala , which, according to the Department of Islamic Development of Malaysia, could lead to confusion with the similar sounding Muslim name for God Allah Ta'ala in the Koran . The ban was lifted a few weeks after the then Malaysian Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi had met with church representatives, who assured him that the term Allah Tala had always been the Iban word for God and had never caused any irritation. It was also pointed out that the Christians and Jews in the Arab world also refer to God as Allah .

Demographic development of the Iban in Sarawak

| year | Total population of Sarawak | Iban in Sarawak | Share in the total population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | 490.585 | 167,700 | ≈ 34% |

| 1960 | 744,529 | 237.741 | ≈ 31% |

| 1970 | 976.269 | 303,462 | ≈ 31% |

| 1980 | 1,235,553 | 368.508 | ≈ 30% |

| 1991 | 1,625,599 | 483,468 | ≈ 30% |

| 2006 | 2,357,500 | 682,400 | ≈ 29% |

Movies

The British military operations during World War II to retake the island of Borneo with the help of recruited local warriors formed the basis for the 1989 Hollywood film Farewell to the King, starring Nick Nolte .

The film Selima and John (2003, orig. The Sleeping Dictionary ) with Jessica Alba is set in Sarawak in the 1930s and is about the love affair between a British colonial official and an Iban woman.

literature

- Benedict Sandin: The Sea Dayaks of Borneo: Before White Rajah Rule . Michigan State University Press, Michigan 1968 ISBN 978-0-87013-122-6 .

- Derek Freeman : Report on the Iban . New edition. The Athlone Press, London 1970 ISBN 978-0-485-19541-5 .

- John Postill: Media and Nation Building: How the Iban became Malaysian . Berghahn Books, New York, Oxford 2008. ISBN 978-1-84545-135-6 .

- Robert Pringle: Rajahs and Rebels: The Ibans of Sarawak Under Brooke Rule, 1841-1941 . Cornell University Press, Ithaca 1970 ISBN 978-0-8014-0552-5 .

- Vinson Sutlive: The Iban of Sarawak: Chronicle of a Vanishing World . New edition. Waveland Press, Long Grove 1988. ISBN 978-0-88133-357-2 .

- Jean-Yves Domalain: Panjamon - I was a headhunter . Piper, May 1998. ISBN 978-3-492-11383-0

Web links

- The House of Singalang Burong - Iban Cultural Heritage

- The Mysterious Iban: A Living Tradition ( Memento from October 31, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Hose, C. / McDougall, W. (1912): The Pagan Tribes of Borneo ; Provided by Project Gutenberg

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. Wadley, Reed / Mertz, Ole (2005): Pepper in a time of crisis: Smallholder buffering strategies in Sarawak, Malaysia and West Kalimantan, Indonesia. In: Agricultural Systems 85, pp. 289-305. doi: 10.1016 / j.agsy.2005.06.012 .

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels: The Ibans of Sarawak Under Brooke Rule, 1841-1941 , London, 1970, p. 20

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , p. 19, footnote 4

- ↑ cf. Newspaper article Time for Bidayuhs to have own identity, says Manyin (May 9, 2002) ( Memento of February 5, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) in the Sarawak Tribune .

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , p. 9

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , p. 30

- ↑ cf. Freeman, D., Report on the Iban , New Edition, London, 1970, pp. 2-7

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , pp. 29-31

- ↑ cf. Sandin, B., The Sea Dayaks of Borneo: Before White Rajah Rule , Michigan, 1968, pp. 31-39

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , p. 17

- ↑ cf. Reasback, C., Window on the World - Sarawak, East Malasia , 2005 ( Memento of the original from March 22, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , as seen on January 17, 2008

- ↑ cf. Gomes, Edwin H., Seventeen Years among the Sea Dayaks of Borneo , London, 1911, pp. 73-75

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , pp. 21-23

- ↑ cf. Linklater, A., Wild People , p. 195

- ↑ cf. Sandin, B., The Sea Dayaks of Borneo , p. 59

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , pp. 21-23 , 50

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , pp. 47–47

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , pp. 50–50

- ↑ cf. Sandin, B., The Sea Dayaks of Borneo , pp. 59-76

- ^ Gavin, Traude (1996): The Women's Warpath: Iban Ritual Fabrics from Borneo . Museum of the University of California.

- ↑ Pua Kumbu: The Legends of Weaving ( Memento December 6, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), viewed November 21, 2008

- ↑ Kurzmann, S., Pantang Iban: A description and analysis of Iban tattooing , in Sarawak Museum Journal 44:65 , 1993, pp. 69-76

- ↑ Zulueta, L. (1980), Iban Tattoo Patterns

- ^ Website of Ernesto Kalum , a Sarawak tattoo artist who offers traditional Iban motifs, viewed October 9, 2008

- ↑ cf. Sandin, B., The Sea Dayaks of Borneo , p. 1

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , p. 39

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , pp. 41f.

- ↑ cf. Sandin, B., The Sea Dayaks of Borneo , pp. 2-4, 28

- ↑ a b cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , pp. 39-42

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , pp. 41ff

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , pp. 46–46

- ↑ cf. Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , pp. 81-95

- ↑ Lim Pui Huen, P. / Wong, D., War and memory in Malaysia and Singapore , 2000, p. 127.

- ^ L Klemen: The Invasion of British Borneo in 1942 . In: The Netherlands East Indies 1941-1942 . Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ↑ Ooi Keat Gin: Prelude to invasion: covert operations before the re-occupation of Northwest Borneo, 1944-45 ( Memento from July 18, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ). In: Journal of the Australian War Memoria (2002).

- ↑ cf. Heimann, JM, The Most Offending Soul Alive: The Life of Tom Harrisson , Hawaii, 1999

- ↑ cf. An account of the Communist Terrorists Ambush inflected on a platoon of the Royal West Kent Regiment, probably ranking amongst the worst during the Malayan Emergency ( Memento of the original from January 27, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , seen on November 12, 2008

- ↑ Osman, S., Globalization and Democratization: The Response of the Indigenous People of Sarawak in Third World Quarterly , 21.6, December 2000, p. 980.

- ↑ The Star (April 26, 2003), Ban on Iban Bible lifted ( Memento of the original from January 29, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ UCANEWS.com (May 5, 2003) MALAYSIA IBAN BIBLE BAN LIFTED AFTER CONSULTATION WITH ACTING PRIME MINISTER ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . Retrieved July 12, 2009.

- ↑ a b Pringle, R., Rajahs and Rebels , p. 247.

- ↑ a b Far Eastern Economic Review, May 30, 1985 issue

- ^ Department of Statistics Malaysia, Population and Housing Census 1991, State Population Report - Sarawak , Kuala Lumpur, 1995, p. 23

- ↑ Census on December 31, 2006, according to [1] , viewed on July 17, 2008