Jeanne Hersch

Jeanne Hersch (born July 13, 1910 in Geneva ; died June 5, 2000 there ) was a Swiss philosopher , educator and writer .

Life

Jeanne Hersch was the daughter of Liebmann Hersch , professor of demography and statistics at the University of Geneva , and his wife Liba Hersch-Lichtenbaum, a doctor in the disarmament department of the League of Nations . Her parents were Polish-Jewish immigrants - the father came from Pamūšis in Lithuania and the mother from Warsaw . Both immigrated to Switzerland from Warsaw in 1904. They were members of the General Jewish Workers' Union , to which Jewish socialist groups from Russia and Poland had come together to fight for a better social, economic and educational position for the Jews under the rule of the Tsar. Her sister Irène was born in 1917, her brother Joseph in 1925. In 1928, Jeanne Hersch graduated from high school with the Matura and began to study literature with André Oltramare in Geneva . In the summer semester of 1929 she studied philosophy with Karl Jaspers in Heidelberg . In 1931 she acquired Swiss citizenship in her hometown of Geneva.

In 1931 she passed her state examination in literature in Geneva with the thesis Les images dans l'oeuvre de M. Bergson . This was followed by two years of postgraduate studies at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes in Paris in 1931, with Karl Jaspers in Heidelberg in 1932 and with Martin Heidegger in Freiburg im Breisgau in 1933. From 1933 to 1956, she taught French, Latin and philosophy at the Ecole internationale (Ecolint ) in genf. In 1935 she taught as a private teacher in Chile and toured Latin and North America. During the summer vacation of 1936 she studied with Gabriel Marcel in Paris. In 1938/1939 she accompanied the royal family in Thailand as the private tutor of the three children, including the future King Bhumibol as the youngest . From 1942 to 1946 she took part in the doctoral colloquium of the philosopher Paul Häberlin , Karl Jaspers' predecessor, at the University of Basel . Häberlin's Lucerna Foundation supported her doctoral thesis with a grant.

In 1946 she received her doctorate in philosophy from the University of Geneva with the dissertation L'être et la forme . There she taught from 1947 as a private lecturer, from 1956 as a professor and from 1962 to 1977 as a full professor at the Chair of Systematic Philosophy . She taught as visiting professor at Pennsylvania State University in 1959 , at Hunter College, State University of New York in 1961, at Colgate University in Hamilton in 1978 and at Université Laval in Québec .

During the Second World War , Hersch volunteered in her adopted home in the women's service (FHD) and during the Cold War in a predecessor organization of the secret resistance organization P-26 .

From 1966 to 1968 she was director of the philosophy department of UNESCO in Paris. On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the UN human rights declaration, she published the basic work The right to be human in 1968 . From 1970 to 1976 she was a member of the Swiss UNESCO Commission and from 1970 to 1972 on its Executive Council.

Jeanne Hersch was a member of the Cusine des Exilés , the Pour l'avenir Foundation , the Société suisse de philosophie , the Société des écrivains suisses , the Comité des Rencontres Internationales de Genève , the Conseil de la Fondation Pro Helvetia and the Union of European Federalists . From 1973 to 1994 she was President of the Karl Jaspers Foundation in Basel.

Her close circle of friends and dialogue partners included the Nobel laureate in literature Czesław Miłosz , the French Jesuit and philosopher Gaston Fessard and the Geneva education director and literature professor André Oltramare, who was also her life partner from 1942 until his death in 1947.

plant

Experienced time: totalitarianism and existential freedom

Her father's stories of his disappointment on the trip to Russia when he learned of the overthrow of the Social Revolutionary Kerensky and the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks shaped her aversion to totalitarian regimes and motivated her to pursue her lifelong struggle for personal and social freedom .

Her encounter with the existential philosopher Karl Jaspers in Heidelberg in 1932 shaped her philosophical life's work. She became his student and he remained her lifelong role model. Jaspers' philosophy was for her the "kingdom of freedom". Hersch translated Jaspers' works and made it known in the French world as a social alternative to Sartre's version of existentialism. Like Hannah Arendt , she had applied his philosophy rather than developed it theoretically. Jaspers meant for her lived clarity, as a prerequisite for truth and honesty. It was the existentialist, anti-totalitarian philosophy of the German philosopher that deeply impressed her:

“I am grateful that there is not only an objective, factual, objective security with him, but also an existential one, which is based on the fact that people are committed to it and are changed and supported by it. It actually means that existence loves clarity as the presence of being. "

In Freiburg, where she attended lectures by Martin Heidegger , she saw Hitler take power.

Philosophy as a commitment to truth

These profound experiences prompted them to be vehemently committed against all kinds of propaganda and political lies. At that time she understood that whoever does not choose where to fight, as long as he has the democratic opportunity to do so, will be rolled like a pebble by politics.

As a young teacher, she published her first philosophical book L'illusion philosophique in 1936 , with which she won the Prix Amiel . In it, she presented the history of philosophy since Plato and Aristotle as a chain of relativized illusions that would only be resolved with Jaspers' realization that nothing could be known. This gave Hersch the opportunity to explain freedom as the starting point for all thinking and to make it the basis of her own philosophy.

Philosophy as a responsibility to people

In 1968 she published her book Le droit d'être un homme (The right to be human) on behalf of Unesco on the 20th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights , the documents she had collected on law, philosophy and poetry from various countries and cultures and with which she showed that human rights can be found in all cultures and are therefore universal and that existential freedom belongs to people because they are people. For this book she received the Human Rights Prize and the Karl Jaspers Prize.

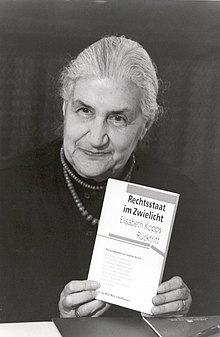

For them, philosophy was an obligation to truth and responsibility towards people. She did not allow herself to be intimidated by personal hostility and repeatedly campaigned where people were to become victims of public campaigns, for example for Elisabeth Kopp , the first female Federal Councilor in Switzerland, and for Peter Regli , the head of the Swiss intelligence service.

She justified her skepticism towards the zeitgeist and her "out of date" considerations as follows:

"If you comment on a topic that is burning in the present, you should always speak against the current."

She accepted to fight against the positions of her own party - the Social Democrats - if she judged something to be right: for example, she campaigned for the use of nuclear energy , for adequate national defense and against the legalization of drugs . For Hersch, drugs negated human rights and the essential human condition, as they made people dependent and unfree. She accompanied the women's movement as critically and constructively as the 1968 movement and the Zurich youth movement .

Pedagogy as education for responsible freedom

Hersch not only taught philosophy, she also worked for 22 years as a teacher at the Ecole Internationale in Geneva, which was founded in 1924 . The “Ecolint” was a reform pedagogical project of the League of Nations, the International Labor Organization , the Jean-Jacques Rousseau Institute at the University of Geneva and the reform pedagogue Adolphe Ferrière . Her experiences, long before the reforms of the 1960s, made her a staunch critic of reform pedagogy . For them, the reform pedagogy of the 20th century consisted of a chain of misguided pedagogical concepts.

She countered the concept of the “new upbringing”, which is based on the independent learning of children, that if the children were free like adults, upbringing would be superfluous.

“Education does not require any dogmatic doctrine as the only possible way or any social model as the only correct one. No, it should only increase the chances of responsible freedom for every person as far as possible. "

For Hersch, the human being is a being (être docile) who can be taught and not only learns:

"To be teachable means not only that you get something from the other, but that you can develop a receptive activity, and this receptive activity is something that you may not think about enough these days."

She turned against the "child-centered" reform pedagogy because the teacher could not be the "copain" (comrade) of the student. The teacher would then be superfluous because the student could learn what he wants and not what is good for him.

“The teacher in the class should actually think much more about what he is teaching in his lessons than about the student. I know that what I am now saying is in deep contradiction to today's psychologization of teaching. "

She saw the youth riots in Switzerland in the 1980s as the result of an anti-authoritarian upbringing with a lack of adult role models and a lack of orientation:

“In reality, one of the sources of unhappiness for some of today's youth is not, in my view, repression, but the absence of real adults in our society. When it says, “everything is allowed”, it means that there is nothing - nothing that forces something, nothing that is worth something, nothing that imposes itself. Since everything is allowed, nothing is expected from anyone. That's what I called the nihilistic void. "

The liberal-democratic socialism

Jeanne Hersch grew up with socialism. Her parents were Polish social revolutionaries , but they not only conveyed socialist commitment to her, but also skepticism towards any kind of utopia. Early on, she attended the “Foyer socialiste international” founded by André Oltramare in 1927 , where she received her political training to gain an understanding of social and political problems. In her book “The ideologies and reality” from 1957 she tried to counter the “ideological failure of today's socialism” to make a “contribution to the renewal of its teaching building”. Their implications are that socialism must commit itself to anti- dogmatism and freedom. Socialism has no philosophical or religious credo and should not have one. The socialists could, however, fall back on an absolute and non-statute-barred value: the free and responsible human person. However, they are not authorized to impose this absolute on others or to determine it more precisely. She wants to see this liberal socialism realized within the framework of democracy:

"I believe that democracy, as it is understood in the West, is the only form of government that is able to guarantee every person the minimum of physical and mental security, without which there is neither freedom, human dignity, nor progress."

For Jeanne Hersch, democracy has its place where people in their historicity are both dependent and active. In search of their own freedom, they would build a civilization:

“What citizens have to expect from the democratic order is not the gift of their own freedom - no political regime can do that, they have to tackle this task themselves - but only an institution of common life that provides the most favorable conditions for each individual for his search for freedom. "

The philosophical amazement

Jeanne Hersch's philosophy and life has a lot in common with Socrates , which she described in her book "The Philosophical Amazement". This earned her the reputation of a "female Socrates". His main philosophical question “How should I live in order to live towards the good?” Was also her leitmotif.

What they have in common is the search for truth based on the moral obligation for the true good, acting in accordance with this knowledge, the question of the just order in the state (polis) and the educational concern, through the process of thinking the soul to shape.

For Socrates and Hersch, “philosophical truth” is an existential truth that is both theoretical and practical. It only exists when it is linked to responsible, free human existence and its recognition and action in order to awaken and practice the deeper sense of true good. According to Hersch, Socrates' “Know Yourself” is not about a mere “mirroring” or “looking”, it is about getting down to business.

In her view, the roots of the natural sciences and humanities are also moral. The hypotheses are strictly checked because the scientist is morally obliged to be as certain as possible about the truth.

It is said that Socrates was sentenced to death "because he spoiled the youth". According to Jeanne Hersch, it happened because he questioned everything: the nature of power, the right of power, etc. His questions were broad and political.

Jeanne Hersch's questions and political work did not always meet with approval. Their lectures on the background of the youth unrest were often disrupted or prevented by young people. In the reception there are hidden allusions that deny it, for example, the ability to “correctly” understand the background to the youth unrest: For the biographer Charles Linsmayer it is clear that “such a fixed worldview will be overtaken over time”:

“Jeanne Hersch's great period was basically the time after World War II. Later, due to her very intelligent way of thinking that was fixed in a closed system, she was no longer able to understand everything as directly and spontaneously pragmatically as younger people could. "

Her struggle for freedom and against injustice was reflected in her numerous books, newspaper articles and lectures. Her clear and simple language made her a bestselling author. She particularly opposed any form of doctrinal and totalitarian thinking. Their fundamental theme was freedom, the intellectual, existential, truly human freedom that can only be developed in a free, democratic constitutional state where human rights are respected and protected. She always advocated the preservation of this constitutional state with determination.

In her numerous lectures, she knew how to meet the audience with her clear language:

“A cow stares, but man can meet the world in amazement and questioning because he has reason and because he has the freedom to make decisions. Maybe he doesn't decide, but he could decide. As a result, he is also responsible for how he decides. "

Your estate is in the Zurich Central Library .

Awards

- 1936 Prix Amiel of the University of Geneva for her first book L'illusion philosophique (The Illusion - the way of philosophy)

- 1941 Prix littéraire de la Guilde du Livre for the novel Temps alternés (manuscript title Chaîne et Trame ; German 1975 encounter, 2010 First Love)

- 1947 Prix Adolphe Neuman d'ésthetique et de morale de la Ville de Genève

- 1972 Awarded an honorary doctorate from the Theological Faculty of the University of Basel

- 1973 Prize from the Fondation pour les Droits de l'Homme

- 1979 Montaigne Prize, Spinoza Medal

- 1980 Max Schmidheiny Freedom Prize

- 1985 Max Petitpierre Prize

- 1987 Albert Einstein Medal

- 1988 UNESCO Prize for Human Rights Education

- 1992 Karl Jaspers Prize

- 1993 honorary doctorate from the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Oldenburg

- 1998 honorary doctorate from the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne

Works

Own works (French)

- L'illusion philosophique. 1936.

- Temps alternés. 1940.

- L'être et la form. 1946.

- Idéologies et réalité. 1956.

- Le droit d'être un homme (The right to be human), 1968. Reading samples from around the world on the subject of freedom and human rights. Idea, concept and selection by Jeanne Hersch, on behalf of UNESCO.

- Karl Jaspers. 1978.

- L'étonnement philosophique (De l'école Milet à Karl Jaspers). 1981.

- L'ennemi c'est le nihilisme. 1981.

- Text. 1985.

- Éclairer l'obscur. 1986.

- Temps et musique. 1990.

Own works (German)

- The illusion. The way of philosophy. Insight, knowledge and education. With a preface by Karl Jaspers, Francke (Dalp TB 320), Bern 1956.

- The ideologies and the reality. Attempt a political orientation. R. Piper & Co., Munich 1957.

- Current Problems of Freedom (Liberté / Freiheit / Freedom / Libertad), Schweizerisches Ostinstitut, Bern 1973 (in four languages).

- The inability to endure freedom. Essays and speeches. Benziger, Zurich 1974.

- Encounter. Roman (= Temps alternés ). Huber, Frauenfeld 1975, ISBN 978-3-7193-1153-7 .

- The hope of being human. Essays. Benziger, Zurich 1976 Reading samples from all over the world on the subject of freedom and human rights. Idea, concept and selection by Jeanne Hersch, on behalf of UNESCO.

- Of the unity of man. Essays. Benziger, Zurich 1978.

- Karl Jaspers. An introduction to his work. Piper (SP 195), Munich 1980.

- The philosophical amazement. Insights into the history of thought. Benziger, Zurich 1981.

- Antitheses to the "Theses on the Youth Unrest 1980" of the Federal Commission for Youth Issues. The enemy is called nihilism. Meili, Schaffhausen 1982.

- Right across time. Essays. Benziger, Zurich 1989.

- At the intersection of time. Essays. Benziger, Zurich 1992.

- First love. Publisher: Huber & Co. AG Buchverlag, Frauenfeld 2010, ISBN 3-7193-1539-8 (original title "Temps alternés", reprint from 1942, only novel by Jeanne Hersch).

- Experienced time. Being human in the here and now. Monika Weber and Annemarie Pieper (eds.), Verlag NZZ Libro, Zurich 2010, ISBN 978-3-03823-597-2 .

As an editor or employee

- Comprehensive school. Practical aspects of internal school reform. Published by the Bernischer Lehrerverein, Haupt (UTB 140), Bern and Stuttgart 1972.

- Karl Jaspers - philosopher, doctor, political thinker. Symposium on the 100th birthday in Basel and Heidelberg. Piper, Munich 1986.

- The right to be human. Reading samples from all over the world on the subject of freedom and human rights. Helbing & Lichtenhahn, Basel 1990, ISBN 978-3-7965-1228-5 .

- The rule of law in twilight - Elisabeth Kopp's resignation. Meili, Schaffhausen 1991, ISBN 3-85805-153-5 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Biography of the Jeanne Hersch Society .

- ↑ sh.ch (PDF) From the answer of the government council of the canton of Schaffhausen to the small inquiry 1/2010 regarding honoring members of the secret organization P26 raises questions. Quote: "The long-standing and well-deserved Schaffhausen City President, SP President and National Councilor Walther Bringolf was just as much a member of the cadre organization for the resistance as the well-known Geneva philosopher and social democrat Jeanne Hersch."

- ↑ Jeanne Hersch: First love. Reprint 2010, with a biography by Charles Linsmayer.

- ↑ on this Jeanne Hersch in “Difficult Freedom”: “The fall of the Tsar in 1917 was a great celebration for us. (…) Everyone thought that freedom and socialism would now find their way into Russia. A little later my father traveled to Russia as the vanguard. He wanted us to come. On the way there he learned of the fall of the Kerensky government and the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks. He returned home immediately. So it happened that I spent my whole life in Geneva, that I became Swiss and Geneva - as a result of the Russian Revolution. "

- ^ Dialogue with Jeanne Hersch, 1996 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Jeanne Hersch: Experienced time. Being human in the here and now. 2010 ( Memento of the original from December 13, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF).

- ↑ Jürgen Oelkers: Jeanne Hersch, School and Reform Education with a quote from Dufour / Dufour: Schwierige Freiheit, Talks with Jeanne Hersch, 1990 (PDF; 216 kB).

- ↑ Jeanne Hersch: The community that does not impose itself on its citizens .

- ↑ Jeanne Hersch - a Swiss philosophy monument .

- ↑ "The right to be human". On the death of Jeanne Hersch. Zeit -fragen No. 68 from June 13, 2000, article in the Internet archive , version from October 15, 2004 ( Memento from October 15, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

literature

- Plans-fixes [video], 1979.

- Emmanuel Dufour-Kowalski: Jeanne H., présence dans le temps. 1999, (with catalog raisonné).

- E. Deuber Ziegler, N. Tikhonov (eds.): Les femmes dans la mémoire de Genève. 2005.

- Annemarie Pieper (ed.): The power of freedom. Small festschrift for the 80th birthday of Jeanne Hersch . Benziger, Zurich 1990.

Web links

- Publications by and about Jeanne Hersch in the Helveticat catalog of the Swiss National Library

- Literature by and about Jeanne Hersch in the catalog of the German National Library

- Lucienne Hubler / AW: Hersch, Jeanne. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Sound documents by and about Jeanne Hersch in the catalog of the Swiss National Sound Archives

- For the 100th birthday of the philosopher Jeanne Hersch , Echo der Zeit from July 12, 2010 on Swissinfo

- Dialogue with Jeanne Hersch from the magazine Sic et Non . 1996

- Website of the Jeanne Hersch Society with events for the 100th birthday on July 13, 2010

- Zurich Central Library: picture gallery

- Juergen Oelkers: Jeanne Hersch, School and Reform Education. (PDF, lecture from June 15, 2010)

- Swiss television «Wissen» from March 17th, 2008: Jeanne Hersch - «Rule of Law in Twilight»

- Jeanne Hersch in the archive database of the Swiss Federal Archives

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hersch, Jeanne |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Swiss philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | July 13, 1910 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Geneva |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 5, 2000 |

| Place of death | Geneva |