Jules Bonnot

Jules Joseph Bonnot (born October 14, 1876 in Pont-de-Roide ( Doubs department ), † April 28, 1912 in Paris ) was a French anarchist and supporter of illegalism . He was the leader of an anarchist group known in the press as "Bande à Bonnot" ( Bonnot gang ) and committed several robberies and murders in 1911 and 1912. His special taste and expensive clothing earned him the pseudonym " Le Bourgeois " among his comrades . He was caught at great expense and his death was widely received.

Life

youth

On January 23, 1887, when Bonnot was ten years old, his mother died in Besançon . Jules' father, a foundry worker and illiterate, took care of the boy's upbringing from this point on. Jules did not have much success at school and left quite quickly. At the age of 14 he started an apprenticeship. He wasn't very motivated and often argued with his superiors. In 1891, at the age of 15, he was sentenced to prison terms for fishing with prohibited equipment and in 1895 for a fight with a police officer at a dance event. After his military service in August 1901, he married the young tailor Sophie-Louise Burdet. After a disappointed love affair, his older brother committed suicide by hanging in 1903 .

Anarchist engagement

It was during this period that Bonnot began the struggle for anarchism. He was dismissed from the Bellegarde Railway because of his political commitment, and no one wanted to employ him anymore. So he decided to go to Switzerland. He found a job as a mechanic in Geneva , where his wife became pregnant. The child, Émilie, died a few days after birth. Bonnot still fought for anarchism and got the reputation of an agitator . So he was expelled from the country.

His skills as a mechanic allowed Bonnot to find a job with a large car manufacturer in Lyon , where his wife gave birth again in 1904. He did not lose his political convictions and denounced injustices and organized strikes , so that he caught the eye of the entrepreneurs.

He moved to Saint-Etienne and became a mechanic for a well-known company. He lived with his family with his union secretary , Besson, who became the lover of Bonnot's wife. To escape the wrath of Bonnot, Besson moved to Switzerland with Bonnot's wife Sophie and their child. Bonnot's political activity increased. Sophie's escape resulted in Bonnot losing his job. From 1906 to 1907 he and his assistant Platano opened two mechanic workshops in Lyon. In 1910 he went to London, where, thanks to his talents, he became the chauffeur of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle , the creator of " Sherlock Holmes ", which brought him experience for his later career as an illegalist , as he carried out his raids with big cars.

Beginnings of the gang

At the end of 1910 Bonnot returned to Lyon and for the first time in history used an automobile for criminal purposes. The police were on his heels, so he left town with Platano. During the trip he was killed by Bonnot. The circumstances are unclear. Bonnot's version boils down to the fact that Platano had seriously injured himself in an accident with his revolver, and Bonnot wanted to relieve him from the suffering. After Alphonse Boudard, Bonnot could not give any other reason, as Platano was closely linked to the Parisian anarchists and thus Bonnot's supporters. Bonnot had appropriated a large sum of money, 40,000 francs , from Platano, which is why a murder hypothesis cannot be ruled out.

At the end of November 1911, at the headquarters of L'Anarchie magazine , headed by Victor Serge , Bonnot met several sympathizers of anarchism who became his accomplices. The most important were Octave Garnier and Raymond Callemin , called "Raymond-la-science" (Raymond, the science) and others who played a lesser role: Élie Monnier called "Simentoff", Édouard Carouy , André Soudy and Eugène Dieudonné , his position could never really be resolved. As supporters of " individual reappropriation ", all of them had already committed theft and were ready for greater deeds. After Bonnot's arrival, the gang was formed. Although the idea of a leader is rejected by anarchists, in practice Bonnot took over the lead due to his age and criminal experience, even if this was left unspoken.

The robbery on the Société Générale

On December 14, 1911, Bonnot, Garnier, and Callemin stole a car to carry out their plans. Based on his knowledge, Bonnot chose a reliable, fast and luxurious Delaunay-Belleville 12 CV, model 1910 in green and black paintwork.

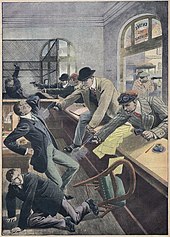

At 9 a.m. on December 21, 1911, Bonnot, Garnier and Callemin and possibly a fourth accomplice (Ernest Caby), the cashier of the Société Générale and his bodyguard, Alfred Peemans, dropped theirs in front of Paris' 148 Rue d'Ordemer. Immediately after Garnier and Callemin had noticed both victims, they pounced on her while Bonnot waited at the wheel. Garnier fired twice, seriously injuring the messenger. Callemin grabbed the shoulder bag and they both fled to the car.

Passers-by who made arrangements to prevent the two of them from escaping, Bonnot tried to drive them away with shots in the air. As soon as Garnier and Callemin got into the car, Bonnot drove away, causing the wallet to fall into the gutter . So Callemin got out to take the money, fired at someone who ran in his direction without hitting him, and got back in the car. According to witness statements, another accomplice intervened at this point. Eventually Bonnot started the car and the gang escaped.

This was the first time an automobile was used in a robbery. The events had a high level of echo due to the bank employee's injuries. The next morning a newspaper article appeared about the incident. The raid was not a great success: the booty consisted of 5,000 francs in cash and 300,000 francs in non-salable securities. The bandits had not taken another bag with 40,000 francs in the confusion. They left their car in Dieppe and returned to Paris. Callemin, who had gone to Belgium, tried in vain to sell the papers there and then got back together with the others. At this point the police uncovered the connection between the robbery and the anarchist scene, which made the incident even more interesting for the press.

A week after the spectacular event, Garnier and Callemin found shelter with Victor Serge and his girlfriend Rirette Maitrejean. Although he disapproved of the gang's methods, he accepted them out of solidarity . Shortly after Garnier and Callemin disappeared, the police searched Serge's apartment, as did all other known anarchists. The couple was then arrested for possession of weapons that an anarchist friend had left behind in a package. The press pounced on the event, calling Serge the "brain" of the gang and speculating that the arrest of the remaining members was imminent. In fact, things turned out differently: younger anarchists like René Valet and André Soudy , who were angry about the arrest of Serge, joined the illegalist group.

More thefts and robberies

The gang continued their journey. On December 31, Bonnot, Garnier and Carouy tried to steal a car in Ghent . They were surprised by the chauffeur, whom Garnier knocked down. A night watchman who was alarmed by the noise and rushed to was shot with a revolver. On January 3, 1912, Carouy and Marius Metge murdered a pensioner and his maid in a break-in in Thiais . There is no evidence that the double homicide was arranged with Bonnot and his gang. Since Carouy was involved in the Ghent incident, the judiciary put the murder on the Bonnot gang's list. On February 27, Bonnot, Callemin, and Garnier stole a new Delaunay-Belleville. A policeman who happened to be Garnier and wanted to check them out in Paris because of Bonnot's risky driving style, was beaten to death by Garnier. The death of a member of the security authorities increased the angry reports in the press and the opinion that the gang must be stopped. The next morning in Pontoise , the trio tried to rob a notary's safe. They were taken by surprise and fled without prey.

During this time Eugène Dieudonné was arrested. He denied any involvement in the gang's criminal activities but admitted knowing Bonnot and sympathizing with anarchism. The cashier, who had already identified Carouy and Garnier in photos, accused him of having participated in the robbery on Rue Ordener.

March 19th marked a high point of public attention when a letter was published in Le Matin . In this, Garnier provokes the police because of their inability to track him down. He had no illusions about his end and wrote: I know that I will be defeated and the weakest, but I will make them pay well for it and make their victory dear . He stated that Dieudonné was innocent of the alleged crimes. The letter was marked with a fingerprint that the police found to be authentic.

On March 25, the habitual trio Bonnot, Garnier and Callemin, accompanied by Monnier and Soudy, prepared for the theft of a De Dion Bouton limousine that they had learned about delivery to the Côte d'Azur. The raid took place in Montgeron . Bonnot shook a handkerchief in the middle of the lane. As soon as the car stopped, the rest of the gang appeared. Believing that the chauffeur would draw a gun, Garnier and Callemin shot him and the owner of the car. According to his testimony, Bonnot had “Halt! You are crazy! Stop! " Screamed. The gang decided to carry out an impromptu raid on the Société Générale in Chantilly . After breaking into the bank, Garnier, Callemin, Valet and Monnier shot three employees, piled rolls of coins and banknotes in a sack, and disappeared to the motor vehicle in which Bonnot was sitting and promptly drove off. The gendarmerie was alerted, but had to let the gang go on their bikes and horses.

End of the Bonnot gang

After this latest robbery, the police increasingly stopped the group's activities. Soudy was arrested on March 30th and Carouy on April 4th. April 7th was the day that brought the police down to Callemin - an important catch for them as he was one of the main characters alongside Garnier and Bonnot. Monnier was hit on April 24th.

April 24th was also the day of an investigation into the home of an anarchist sympathizer in Ivry-sur-Seine by the number two of the Sûreté nationale , Louis Jouin, who was in charge of the investigation into the Bonnot case. In one room he met Bonnot who immediately killed Jouin with a revolver and then fled. Injured by gunfire, he went to a pharmacist for treatment. He tried to make him believe he'd fallen off the ladder, but the ladder linked Bonnot to the Ivry incident and notified the authorities. The police were able to narrow down Bonnot's whereabouts and combed the area. On April 27, police arrested Bonnot in his hiding place in Choisy-le-Roi . Bonnot still had time to sneak away, so the chief of security preferred to circle the area and wait for reinforcements, whereupon Bonnot retreated to the detached house. A long siege began in which the Prefect of Paris Louis Lépine took part. More and more troops withdrew together even one Zouaves - Regiment with an advanced Hotchkiss - machine gun . Numerous onlookers were drawn to the spectacle. Bonnot showed up from time to time on the steps of the house to shoot his enemies, where he was regularly received with volleys from which he could evade unharmed.

As time passed and the police hesitated to end the siege, Bonnot gradually lost interest in his attackers and began to draw up his will . Lépine finally decided to blow up the house with dynamite. Badly injured by the explosion, Bonnot took the time to finish the will in which he acquitted several people, including Dieudonné, of complicity. While the police under Guichard attacked, Bonnot managed to get off a few hits from his revolver before he was wounded himself. He died shortly after arriving at the Hôtel-Dieu de Paris .

After Bonnot's demise, only two members of the gang remained free: Valet and, above all, Garnier, who had perpetrated most of the murders. They were located on May 14th in a house in Nogent-sur-Marne . The police were hoping for a "gentle" arrest, but due to their conspicuous behavior they were discovered by Valet and Garnier, who holed up in the house. A new siege began, very similar to that of Choisy, with large numbers of police and military personnel and clusters of gawkers watching closely all the ventures. For more than nine hours, Valet and Garnier managed to keep the "small army" at a respectful distance. Finally, a regiment of dragons managed to blow up the house. The police then attacked in the storm and killed the two men. Then she had to fight the angry crowd that wanted to tear the two bandits to pieces post mortem.

The survivors' processes

The trials of the surviving members of the Bonnot gang took place in February 1913. The main defendants were Callemin, Carouy, Metge, Soudy, Monnier, Dieudonné and Victor Serge. In addition, there were some people who were accused of helping the gang on various occasions. Callemin was the main surviving member and he used the tribunal as a platform to display his revolutionary stance. He denied all evidence, but in a form that left no doubt about his guilt. Carouy and Metge were specifically charged with Thiais' double homicide. They denied their involvement, but were found fingerprinted. Monnier and Soudy were charged with their involvement in the Chantilly raid, which witnesses unequivocally identified them. Victor Serge was presented as the head of the gang at the beginning of the trial, which he vigorously rejected. He stated that at no time did he benefit from the gang's raids.

The only doubtful case was that of Dieudonné, who was accused of complicity in the break-in on Rue Ordener. Bonnot and Garnier protested his innocence before their death. Dieudonné presented a documented alibi after being in Nancy at the time of the crime . Several witnesses, including the cashier robbed by the gang, confirmed his presence at the scene.

In the end Callemin, Monnier, Soudy and Dieudonné were sentenced to death , Carouy and Metge to life-long forced labor. Carouy later committed in his cell suicide . Victor Serge was sentenced to five years in prison. Although he managed to defend himself against allegations of being the "brain" of the gang, the revolvers found during the arrest were his undoing. Callemin spoke at the delivery of the verdict. While he had previously denied having taken part in the attack on Rue Ordener, he now confessed and protested Dieudonné's innocence. This statement was used by Dieudonné's attorney Vincent de Moro-Giafferi to address an appeal for clemency to President Raymond Poincaré , which downgraded the sentence from execution to life-long forced labor. The other three sentenced to death were guillotined on April 21, 1913 in front of the Prison de la Santé in the 14th arrondissement of Paris .

reception

After Bonnot was not discussed for a long time, more than half a century later, in May 68 , some members of the building's occupation committee , especially enragés , anarchists and situationists, renamed the Caillavès room of the Sorbonne to Salle Jules Bonnot and used it as a conference venue of the casting committee. In the same year a book was published about the gang à Bonnot and in 1969 a film of the same name (by Philippe Fourastié with Jacques Brel , Annie Girardot and Bruno Cremer ). The Bonnot gang was also featured in the popular television series Les Brigades du Tigre in the 1970s. The last adaptation for the cinema took place in 2005 with Jacques Gamblin as Jules Bonnot.

literature

- Non-fiction

- Alphonse Boudard : Les Grands Criminels . Edition Le Pré aux Clercs, Paris 1990, ISBN 2-253-05365-1 .

- Wiliam Caruchet: Ils ont tué Bonnot. The rélevations des archives policières . Calmann-Lévy, Paris 1990, ISBN 2-7021-1869-0 (The author, a lawyer, bought all the police files on the gang à Bonnot from a public sale)

- Frédéric Delacourt: L'Affaire bande à Bonnot . De Vecchi, Paris 2000, ISBN 2-7328-4363-6 (Grands procès de l'histoire)

- André Colomer: A nous deux, Patrie! La conquete de soi-meme . Edition de l'Insurgé, Paris 1925 (especially the 18th chapter "Le Roman des Bandits Tragiques")

- Jean Maitron: Ravachol et les anarchistes . Gallimard, Paris 1992, ISBN 2-07-032675-6 (contains memoirs from Callemins)

- Richard Parry: The Bonnot Gang . bahoe books , Vienna 2017, ISBN 978-3-903022-44-7

- Novels

- Pino Cacucci : Better to aim at the heart Edition Nautilus 2010, ISBN 978-3-89401-722-4

- Bernard Thomas : anarchists. The short but dramatic life of Jules Bonnot and his accomplices (“La Bande à Bonnot”) . Walter publisher, Olten 1970.

- Bernard Thomas: La Belle époque de la bande à Bonnot . Fayard, Paris 1989, ISBN 2-213-02279-8 .

- comics

- Florenci Clavé, Christian Godard : A lot of blood for expensive money. The short but dramatic life of Jules Bonnot and his accomplices . Karin Kramer Verlag , Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-87956-163-X ( description from DadA ).

Web links

- Michael Zaiser: The Bonnot Gang Jungle World , October 4, 2000, accessed June 24, 2018

- Historical articles and photos (fr.) In “Magasin Pittoresque” accessed February 3, 2008

- The Invention of the Getaway Cars Spiegel Online Photos and Backgrounds, accessed June 24, 2018

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alphonse Boudard, Les Grands Criminels , Le Livre de Poche, 1990, ISBN 2-253-05365-1 , p. 35-36

- ^ Commissaire Jean Belin, Trente ans de Sûreté Nationale

- ↑ In the original: “Depuis que la presse a mis ma modeste personne en vedette, à la grande joie de tous les concierges de la capitale, vous annoncez ma capture comme évidente. Je vous déclare Dieudonné est innocent du crime que vous savez bien que j'ai commis… Je sais que cela aura une fin dans la lutte qui s'est engagée entre la société et moi. Je sais que je serai vaincu, je suis le plus faible. Mais j'espère bien vous faire payer cher cette victoire. ” Cez Jirlin , accessed November 10, 2008

- ↑ cf. Enragés et situationnistes dans le mouvement des occupations , Paris, Gallimard, 1968; et Internationale situationniste , n ° 12, 1969, p. 22.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bonnot, Jules |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Bonnot, Jules Joseph (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French anarchist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 14, 1876 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Pont-de-Roide |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 28, 1912 |

| Place of death | Paris |