Julius tomb

The Julius tomb is a funerary monument for Pope Julius II executed by Michelangelo Buonarroti and his assistants in the form of a two-storey wall tomb with seven statues , including the famous horned Moses . The tomb, made of Carrara marble , is in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome. The work took about forty years to complete, from 1505 to 1545. The tomb, however, is a cenotaph . Julius II rests together with Sixtus IV under a simple marble slab in St. Peter's Basilica below the monument to Pope Clement X. Of all people , the Pope who wanted to rebuild St. Peter's for his monumental tomb is buried in one of the simplest, barely noticed papal tombs .

History of origin

Picking

The tomb was commissioned by Pope Julius II from the Della Rovere family in 1505, just two years after he took office. Michelangelo, around 30 years old, was already a celebrated sculptor at this point. It is possible that it was Giuliano da Sangallo , who was familiar with Michelangelo's work in Florence, who drew the Pope's attention to Michelangelo. Julius had Michelangelo summoned to him from Florence, where important projects such as the fresco of the Cascina battle were abandoned. The contract provided for the enormous sum of 10,000 ducats (for comparison: the master received 350 ducats for the Roman Pietà , which was completed around five years earlier ), from which, however, the material and auxiliary work / assistants had to be paid. The commissioning of the tomb was the beginning of a complicated relationship between these two great Renaissance people, marked by rifts, but also by affection and mutual respect.

Work on the work was carried out sporadically over four decades, repeatedly interrupted by other orders that the master could hardly avoid. The obligation to complete the tomb, which had been suspended for such a long period of time, represented a continuing heavy burden for Michelangelo (the master spoke to his biographer Ascanio Condivi of the “tragedy of the tomb”). Verspohl writes: “What should have been a triumph for him developed… into a curse, into a tragedy of his life.” Müller writes: “[Michelangelo] had to struggle with the adversities and soul troubles for a full forty years He grew out of this brilliant and honorable commission. ”In the course of these four decades the designs for the tomb were changed at least six times, with the dimensions (at least from the second design) and the number of decorative figures becoming smaller and smaller.

Work on the Julius Tomb began during Michelangelo's second stay in Rome from 1505 to 1506. Since Julius II was already over 60 at the time of commissioning, the Pope urged that it be carried out as quickly as possible. Michelangelo presented the first drafts to his client in 1505. He spent the winter months of 1505/06 in the marble quarries of Carrara to supervise the excavation of the marble for the funerary monument. The first blocks of marble arrived in Rome at the beginning of 1505 and were taken to the master's workshop near St. Peter.

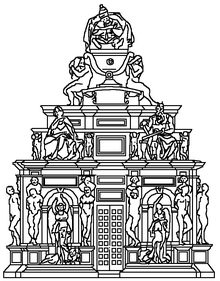

Original plans (1505)

Since no drafts by the master himself have survived, there is relatively little reliable information about the originally planned shape of the grave monument. The only sources are the biographies of Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi , especially the latter. It is clear that the tomb, as it can be seen today in San Pietro in Vincoli, hardly bears any resemblance to the original designs. The always exuberant Vasari describes the tomb in the Vite , as it was shown in the original drawings, as "the greatest testimony to Michelangelo's genius, which surpassed any ancient and imperial tomb in terms of beauty and magnificence as well as ornamentation and richness of the statues".

A free-standing mausoleum ( free grave) with a rectangular floor plan in the shape of a three-storey step pyramid was originally planned . According to Vasari, the tomb should have sides of twelve and eighteen cubits (braccia) in plan (7.2 and 10.8 m). The height should be around eight meters or more (Grimm comes to 30 feet). The monumental work should be provided with at least life-size statues. Most art historians assume with Vasari and Condivi about 40 or a little more statues for this first draft. Grimm even counts over 50 statues. Gardner / Kleiner, on the other hand, assume around 28 statues. The statues were partly free-standing, partly embedded in niches or planned against pilasters . Bas-reliefs in bronze were also provided for the tomb. It is clear that such an abundance of statues, some of which were completely different, must have been particularly attractive to Michelangelo, who saw himself as a sculptor and preferred this discipline over all other arts.

Clothed female figures (in the niches) and unclothed male figures (leaning against pilasters, surrounding the female figures) were planned for the first floor. At the feet of the female statues there should be smaller statues, which, according to Grimm (by the Pope?), Should represent defeated cities. Usually it is assumed with Vasari that the female figures are goddesses of victory and the male figures are prisoners / slaves. Argan / Contardi give the following interpretation: The goddesses of victory and prisoners can be interpreted on the one hand as an allusion to the classic Roman theme of imperial triumph , but on the other hand as a symbol of the Christian victory over death . The connection / reconciliation of pagan antiquity as an aesthetic ideal and Christian modern times is a recurring theme in Michelangelo's work.

Condivi sees in the "prisoners" allegories of the arts, which would have disappeared with the death of the Pope, since there would never be a man who would promote the arts like this. Ua Grimm and von Einem this interpretation connect. One assumes that Michelangelo was inspired in his plans by Antonio Pollaiuolo's tomb for Pope Sixtus IV in St. Peter, whose sarcophagus contains representations of the arts, sciences and virtues. The master may have been looking for new forms of depicting the liberal arts , as these had never been depicted as naked male figures in chains before. The “goddesses of victory”, about which Condivi does not comment, could then be interpreted as allegories of the (victorious) virtues .

The entrance (entrances) to the accessible mausoleum, in which the Pope's sarcophagus would have been located, was provided for one or both of the narrow sides . The apostles Paul and Moses as well as allegories of the vita activa and the vita contemplativa were supposed to be placed at the corners of the second floor . While Vasari and Condivi unanimously state only these four figures, Grimm assumes a total of eight seated statues for this level. A figure of the Pope himself enthroned on the catafalk is believed to be the planned coronation of the monument . The catafalque should be supported by two figures, according to Vasari two angels, according to Condivi allegories of heaven and earth.

In the history of the papal graves, the design from 1505 had no forerunners in this form, as a free grave accessible from all sides. In Vasari there is an allusion to the mausoleums of Roman emperors. At least for the first floor of the tomb, von Eine sees similarities with Roman tombs, but not for the upper part of the construction. Von One sees similarities in the conception of a free grave with the traditional idea of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem; a "reconstruction" of the same by Leon Batista Alberti in the Cappella Ruccelai in the church of San Pancrazio in Florence was known to Michelangelo. Apart from such rather typological similarities, von One sees greater similarities in terms of construction, proportions, ornamentation, etc., with Andrea Sansovino's wall grave for Ascanio Sforza in the Church of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome, which was also commissioned by Julius II in 1505.

The original design of the tomb was so gigantic in terms of its size and number of statues that it would have taken decades to complete, even if Michelangelo had worked on it continuously. Not only the statues, but also the architectural elements with their diverse arabesques and other ornaments, the bronze work, etc. would have meant an enormous amount of work. Rolland speaks of a "feverish delirium of plans" that the Pope and his artist forged together. The failure of these early plans was almost inevitable.

The original plan was to build the tomb in Alt-St. Peter , possibly directly above the tomb of the apostle Peter . It soon became apparent, however, that the old basilica would not offer enough space for the planned gigantic monument. Instead of adapting the plans for the tomb of the church, Julius decided to build a new church - the idea for the new St. Peter's Basilica was born. In this the grave monument should be placed in the choir.

As early as 1506, Pope Julius, who was unsteady and constantly making new plans, abandoned the plans for the grave monument in order to push ahead with the new building of St. Peter's Church, led by Bramante . The Pope refused any further payment to Michelangelo, so that he had to borrow money from the banker friend Jacopo Galli in order to be able to pay workers and marble. The deeply disappointed Michelangelo, who suspected an intrigue by the architect Bramante directed against him, went to Florence in the spring of 1506 against the will of the Pope. It is not unlikely that Michelangelo actually fell victim to the intrigues of Bramante and other artists in Rome, who saw in Michelangelo a rival for the pope's favor and funding. In 1508 Michelangelo returned to Rome , long since reconciled with Julius, whom he had meanwhile erected a bronze statue in Bologna . But instead of finally pushing ahead with work on the tomb, the Pope commissioned Michelangelo to work on the ceiling and wall frescoes of the Sistine Chapel , which were completed in November 1512.

Second project (1513)

Julius II died in February 1513. In May 1513, a new contract was drawn up between Michelangelo and the executors of Julius II, which provided for a new version of the tomb, at least reduced in terms of the number of statues, as Julius himself wished shortly before his death would have. The contract stipulated that Michelangelo should work exclusively on the tomb, the work should be completed within seven years. The fee was increased from 10,000 to 16,500 ducats. The master rented a house near the Trajan's Forum (Marcello dei Corvi), where the marble was moved. Stonemasons were hired and Michelangelo, after working on the ceiling frescoes of the Sistine Chapel, happy to finally be able to work as a scultore again, set to work with renewed vigor.

A monument with a rectangular floor plan was now planned, but only with three free-standing sides, thus a wall grave. Grimm assumed, probably erroneously, "a single marble wall leaning against the church wall". The originally intended burial chamber was eliminated, so it was no longer a mausoleum. The number of sculptures that should adorn the tomb had decreased significantly. The first floor was in principle still in line with the original plans, albeit in a reduced version and with only three free-standing sides. The huge structure above the first floor shows similarities with an altar construction ( cappelletta ).

For the base of the second floor, seated figures were again provided, including Moses. Between these, in an elevated position, in the cappelletta , a seated statue of the Pope was to be enthroned, surrounded by two winged angels, symbolizing the ascent into heaven. This symbolism is already present in medieval tombs, including papal tombs. Above the ensemble with the papal figure is a Madonna with the child (this could have been planned as a bas-relief instead of a statue or even just as a painting). One recognizes a “remarkable” resemblance in the Madonna with the Child to Rafael's Sistine Madonna for Julius II. The figures of the cappelletta should exceed the other figures in size, since they would have been farthest from the viewer. It is unclear whether the cappelletta itself should only be planned as a flat wall decoration or protrude far into the room from the wall, so that there would have been space for side niches (with statues) or the like. Nothing is known about the planned erection of the tomb. Grimm already accepts San Pietro in Vincoli for this stage .

Although it was a reduced version in terms of the number of figures, this monument would have exceeded the original design in terms of the complexity of the iconography and possibly also the size. In the summer of 1513, Michelangelo commissioned Antonio del Ponte a Sieve to carry out the architectural elements of the first floor of the tomb, which were incorporated into the actual version of the monument.

Between 1513 and 1515, Michelangelo worked on the Moses figure, which was originally planned as the corner figure of the rectangular open grave. The completion of the Moses took place shortly before the erection of the tomb in San Pietro in Vincoli. The unfinished statue was stored in Michelangelo's workshop in Rome for about four decades. At around the same time, Michelangelo also created two slave figures (according to Borsi two years before Moses), which, however, did not go into the tomb and are now in the Louvre in Paris. Rough drafts of two statues, possibly slaves, which are now in the Casa Buonarroti in Florence, possibly also date back to this time.

Dying slave , Louvre , Paris

Design of a wall grave for Julius II, attributed to Michelangelo, Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York

Design of a wall grave for Julius II, attributed to Michelangelo, 1513. Uffizi , Florence

The slave or prisoner figures were and are traditionally associated with the Julius tomb by art historians - such a connection is obvious due to the early designs that clearly included such figures. More recently, however, voices have been heard denying such a connection.

In his Michelangelo biography, Grimm speaks with admiration of the dying slave: “Perhaps the delicate beauty of this dying youth is even more pervasive than the power of Moses… When I say that it [the statue of the dying slave ] is the most sublime piece of sculpture for me is, I do it in memory of the masterpieces of ancient art. "

Third project (1516)

In July 1516 a new contract is drawn up with the Della Rovere, in which the number of statues is reduced once more. The period of completion was extended to nine years. The front of the first floor remains unchanged, but the two sides of the first floor connected to the wall are reduced to a niche (about three meters). A Victoria and prisoner statues were planned for the sides. The upper cappelletta structure of the 1513 draft is abandoned in favor of a significantly smaller structure. The statue of the Pope should be on the second floor of the facade, supported by two seated figures, based on the subject of the Pietà , crowned by a Madonna with the child. According to this design, the Moses figure should be in the niche on the left of the second floor as seen from the viewer.

Leo X , the successor to Julius II, came from the Florentine Medici family . If the Medici and the Della Rovere were initially allies, the relationship between the two families turned into open enmity from around 1516, so that it was no longer possible to continue the tomb project under the eyes of the new Pope from 1516. In 1516 Julius II's heirs released the master from his contract. In the following years, Michelangelo was called upon by his early patrons, the Medici.

In 1522 the Della Rovere demanded back payments made for the tomb and in 1524 they threatened a lawsuit. At the end of the 10s / beginning of the 20s, Michelangelo resumed work on the tomb in Florence. Some art historians assume that four unfinished prisoner statues (the so-called Boboli slaves ) (today in the Galleria dell'Accademia , Florence) and the statue of a victor (today Palazzo Vecchio , Florence) date from this period. Other art historians date the Boboli slaves and the victor to a point in time after 1532. None of these five statues, although originally intended for the Julius tomb, was incorporated into it.

The four slave statues are typical of the non-finito , the incomplete, in Michelangelo's work. The four sculptures have therefore always been the focus of Michelangelo's research. Art historians have repeatedly speculated whether this non-finito is merely due to the master's chronic overload (this is, in a sense, the obvious, obvious explanation), or whether this was intended by Michelangelo. Art historians point out that the non-finito reflects Michelangelo's idea that the figures are already contained in the stone and that the sculptor's art “merely” consists of freeing them from the superfluous material that surrounds them.

The statues were in the master’s studio in Florence until the master’s death. In 1586 they were brought to the Boboli Gardens of Palazzo Pitti , where they were symbolically placed in a grotto. They were there until 1908 when they were moved to their current location, the Galleria dell'Accademia.

Winner , Palazzo Vecchio , Florence

Young slave , Galleria dell'Accademia , Florence Atlas , Galleria dell'Accademia , Florence Bearded slave , Galleria dell'Accademia , Florence Awakening slave , Galleria dell'Accademia , Florence

Fourth project (1526)

In 1526, Michelangelo proposed a new version of the funeral monument to the Pope's heirs, according to which a wall grave with only twelve statues should now be carried out. There is hardly any reliable knowledge about this project status. Michelangelo had probably already completely eliminated the remaining side niches in this phase, so that the result was clearly pointing in the direction of the actual grave monument. The Della Rovere did not agree with this version, which was now much reduced compared to earlier drafts.

Fifth project (1532)

After the work on the grave monument had still not made significant progress, the Della Rovere decided to demand a solution. Another treaty was drawn up (1532) stating that the monument was to be erected in San Pietro in Vincoli, Julius' titular church as cardinal , with Michelangelo carrying out six statues himself and directing the work. The work should be completed within three years. But even this contract could not be fulfilled by Michelangelo, as new orders from Popes Clement VII and Paul III. (especially the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel ) claimed all its strength. In November 1536, Pope Paul III issued even a motu proprio to free the artist from his obligations towards the Della Rovere.

In the 1530s and early 1540s, the "Tragedy of the Julius Tomb" for Michelangelo reached its climax. Master was accused of taking large deposits illegally, and was even accused of usury. Michelangelo vigorously defended himself against these allegations.

Sixth and last project (1542–1545)

In 1541, Michelangelo had just completed the Last Judgment, Paul III sat down. at the Della Rovere that other artists should complete the Julius tomb under Michelangelo's supervision. Julius II's heirs accepted and on August 20, 1542 the last contract was drawn up.

The tomb was finally completed in the years 1542 to 1545. In the end, Michelangelo probably only executed Moses, who was now at the center of the funerary monument, by hand and without the help of assistants. The statues of Leah and Rachel were either made by the master with the assistance of his assistant Raffaello da Montelupo or by the latter alone. The three remaining statues (a prophet, a sibyl and the Madonna with the child) were sketched by Michelangelo in 1537, but were completed by assistants. For the architectural elements of the first floor, work was used that had already been carried out by Antonio del Ponte a Sieve around 1513 (see above). The architecture of the upper floor was carried out by Giovanni di Marchesi and Francesco d'Urbino.

In 1545, about 40 years after the commissioning, the tomb was finally erected in its present form in San Pietro in Vincoli.

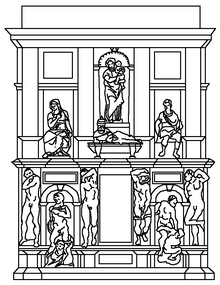

general description

The grave monument is designed as a two-storey wall grave. Müller writes of a "fairly baroque wall construction" that makes an "unpleasant impression". The first floor still bears the reminiscence of one of the narrow sides of the original design with two richly ornamented niches. The Moses statue is in the center of the first floor. In the niche on the right from the viewer there is the statue of Lea as an allegory of the vita activa , in the left niche that of Rachel as an allegory of the vita contemplativa , both in a standing position.

The architecture of the second floor is characterized by four towering pilasters , which form three niches of the same size. In the right niche there is a prophet, in the left niche, above the Vita Contemplativa, a sibyl , both in a seated position. In the very center of the monument, above the statue of Moses, Michelangelo placed a statue of Julius II in a lying position. In the middle niche behind and above the papal figure is the upright Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus in her arms. This ensemble of the resting figure of the Pope and the Madonna with the Child placed above it can already be found in a similar form in the second draft from 1513. With the iconographically familiar representation of the dead in a lying position on a cline , the head supported with one arm, an Etruscan theme becomes Originally recorded, which shows the dead taking part in a banquet in the afterlife . Above the middle niche, crowning the monument, is the papal coat of arms.

The monument is richly ornamented, this applies in particular to the first floor. The ledges above the two lower niches on which the Sibyl and the Prophet are enthroned are each supported by two male caryatids in relief .

What is striking is the dominance of the Moses figure in the ensemble, opposite to which the figure of the resting Julius - actually the main figure of the grave monument - almost disappears. It can be assumed that this disproportion was not planned in this way and is more due to the fact that the larger than life-size Moses, created earlier than the other figures, was designed for an earlier, more monumental version of the tomb and was not reduced in size to the last Version wanted to insert.

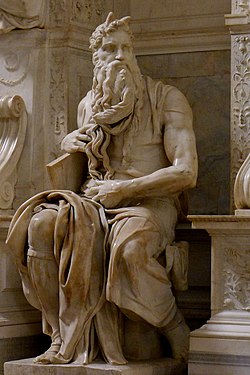

The Moses

The Moses is undoubtedly the most important figure in the Julius tomb, if only for the reason that it is the only statue that Michelangelo undoubtedly executed alone. It is therefore traditionally the commentators' greatest attention. The master himself seems to have been satisfied with his work, as Michelangelo's following statement to his biographer Condivi shows: "This one statue is enough to pay homage to the tomb of Pope Julius."

description

The statue of Moses, made from a block of Carrara marble , is 2.35 high. The prophet is depicted in a sitting position, so the statue would measure about three meters upright. The statue rests on a low pedestal and is slightly pushed out of the monument so that the other sculptures appear as background figures. Moses is represented at the moment when he returns from Mount Sinai with the tablets of the law and witnesses the dance of the Israelites around the golden calf . The right arm is supported on the tablets of the law, the left arm is bent, the hand rests loosely in the lap. The head with the thick, wavy hair and the thick strands of the beard flowing down to the chest - whose technical mastery is praised by Müller as incomparable - is turned about 45 ° to the left, the stern, disapproving look is undoubtedly the one dancing around the golden calf People. According to the biblical tradition, only moments later, Moses will shatter the tablets of the law - still intact in Michelangelo's representation - on the ground for the wrongdoing of his people. The prophet is dressed in a sleeveless tunic with lavish folds.

The - iconographically common - representation of Moses with horns (which allowed contemporary viewers familiar with this iconography to immediately recognize Moses as such) is based on a mistranslation of the Hebrew verb "qāran" ( קָרַן), which can be correctly translated as "radiant". In the Vulgate , on which Michelangelo also orientated himself, "cornuta" (horned) is translated instead due to an incorrect vocalization .

Michelangelo portrayed his Moses as a powerful hero in the ancient tradition. Features such as muscles, tendons and veins are anatomically precisely worked out. The larger-than-life, tension-charged statue with the mighty horned head and muscular limbs gives the viewer the impression of laboriously restrained strength, which in the next instant will be discharged in an outburst of anger.

Jacob Burckhardt writes: “Moses seems to be represented at the moment when he sees the veneration of the golden calf and wants to jump up. It lives in its form, the preparation for a massive movement, as one might expect from the physical power with which it is equipped only with trembling "Similar. Luebke ," When saw the flashing eyes just the sacrilege of worship of the golden calf so violently an inner movement flashes through the whole figure. Shaken, he grabs the wonderfully flowing beard with his right hand, as if he wanted to stay under control of his movement for a moment and then start driving all the more shattering. "

A feature highlighted by many commentators is the statue's terribilità (from Italian terribile : "terrible, terrible") - a trait that his contemporaries also attribute to the master himself, but which was also attributed to the Pope Julius. Commentators such as Grimm and Von Eine therefore see features of the Pope as well as elements of a self-portrait of the master in the Moses statue. Grimm writes: "It is as if this figure were the transfiguration of all the tremendous passions that filled the soul of the Pope, the image of his ideal personality under the figure of the greatest, most powerful people's leader ..." And further: "All the power that Michelangelo possessed ... he showed in these limbs and the demonic, quick-tempered violence of the Pope in his face. "

Possible role models

As a possible model for Michelangelo Moses mentions Andrea di Bonaiuto's fresco The Triumph of St. Thomas in the Spanish Chapel of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. The greatest influence on Moses is seen by one in Donatello's seated figure of John the Evangelist (1408–1415), who until 1537 stood with the three other evangelists in the four large niches next to the main portal of the Florentine Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore and has been since 1936 located in the Museo del Opera del Duomo. Von Eine highlights the strong contrast between Donatello's static representation and the dynamism and liveliness of Michelangelo's Moses. In the naturalness and dynamism of the statue, von Eine sees influences from Hellenistic art , with which Michelangelo dealt intensively. In this context, von Eine specifically mentions the torso of the Belvedere , which had been found a few years earlier in Rome and which Michelangelo was well known to. In Michelangelo's own work, von Eine forerunners of Moses sees especially the prophets Joel, Jeremiah and Daniel from the Sistine ceiling frescoes.

reception

Michelangelo's Moses is likely to be one of the most popular sculptural works. It was and is considered by many connoisseurs as the most important artistic creation of Michelangelo, as the work in which the genius of the Scultore reaches its climax. Vasari judges that no modern or ancient statue can compete in beauty with Moses.

Goethe wrote about the statue in 1830: “I can't think of this hero other than sitting. Probably the overpowering statue of Michelangelo on the tomb of Julius the Second has seized my imagination in such a way that I cannot get away from it. "

Even Sigmund Freud , the founder of psychoanalysis, dealt extensively with the statue and published in 1914 an anonymous 22-page treatise on ( The Moses of Michelangelo ). Freud states that "no picture has ever had a stronger effect". He comes to the conclusion that the dynamics in the picture result from a sequence of movements. While dancing around the golden calf, Moses rises to raise his voice and hand, and the tablet of the law threatens to slip away from his other hand. In the movement of lifting the movement goes back to a sitting movement, because Moses tries - like every person in such a situation - to get a grip on the boards again. Freud shows this movement in sketch form. The movement is, so to speak, frozen in the marble.

Grimm sees Michelangelo's statue of Moses as the “crown of modern sculpture. Not only in terms of thought, but also in view of the work, which increases from incomparable execution to a subtlety that could hardly be carried further. ”“ Anyone who has seen this statue once ... its impression must remain forever. She is filled with a majesty, a self-confidence, a feeling as if the thunders of heaven were at this man's command, but before he unleashed it, he had to conquer himself, waiting to see whether the enemies he wants to destroy would dare to attack him. "

Müller praises the "great beauty" of the face and the impression of liveliness that the naked body parts convey. At the same time, “a certain pursuit of an effect” cannot be overlooked.

Gardner / Kleiner, like many other commentators, point out the latent, seemingly near-erupting emotional and physical energy of Michelangelo's Moses. In this respect, the master has surpassed every pictorial work since the time of Hellenism.

swell

- Ascanio Condivi

- Vita di Michelagnolo Buonarroti raccolta per Ascanio Condivi da la Ripa Transone (Rome 1553) . Part I: Full text with a foreword and bibliographies (Fontes. 34) full text

- The life of Michelangelo Buonarotti. Michelangelo's life is described by his pupil Ascanio Condivi. Translated from the Italian. u. ext. by Hermann Pemsel. Munich 1898.

- Giorgio Vasari

- Le vite de 'piú eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri . First edition Florence 1550. Second extended edition Florence 1558.

- The life of Michelangelo . Edited by Alessandro Nova. Arranged by Caroline Gabbert. Newly translated into German. by Victoria Lorini. Berlin 2009. (Edition Giorgio Vasari), ISBN 978-3-8031-5045-5 .

literature

- Giulio Carlo Argan, Bruno Contardi: Michelangelo. Ediz. inglese, 9th edition. Giunti Editore, 1998, ISBN 88-09-76249-5 .

- Stefano Borsi: The Sixteenth Century: the Golden Ages. In: Marco Bussagli (Ed.): Rome. Art and Architecture. Köneman 1999, pp. 402-439.

- Charles Clément: Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raffael, art and artists of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. EA Seemann publisher, 1870.

- Enrico Crispino: Michelangelo. Giunti Editore, 2001, ISBN 88-09-02274-2 .

- Charles de Tolnay: Michelangelo. Volume 4: The Tomb of Julius II, Princeton 1954.

- Christoph Luitpold Frommel (Ed.): Michelangelo. Marble and Spirit: the tomb of Pope Julius II and his statues . Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2014, ISBN 9783795429157 .

- Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner: Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective. Volume 2, 13th edition. Publisher Cengage Learning, 2010.

- Herman Friedrich Grimm: Life of Michelangelo. Volume I, 1860.

- Friedrich Müller: Life and works of the most famous builders, sculptors, painters, copper engravers, form cutters, lithographers, etc. From the earliest art eras to the present day. Ebner & Seubert publishing house, 1857.

- Erwin Panofsky: The First Two Projects of Michelangelo's Tomb of Julius II. In: The Art Bulletin. 19, 1937, pp. 561-579 JSTOR

- Joachim Poeschke: The sculpture of the Renaissance in Italy. Volume 2, Munich 1992.

- Volker Reinhardt: The Divine: The Life of Michelangelo. Biography, Verlag CH Beck, 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-59784-8 .

- Angelo Tartuferi: Michelangelo. Pittore, scultore, architetto. Con gli affreschi restaurati della Cappella Sistina e del Giudizio universale. Ediz. tedesca, ATS Italia Editrice, 2001, ISBN 88-87654-61-1 .

- Henry Thode: Michelangelo - critical examination of his work. Volume 1, Berlin 1908.

- Franz-Joachim Verspohl: Michelangelo Buonarroti and Pope Julius II. Moses - military leaders, legislators, muse leaders. (= Kleine Politische Schriften Volume 12), Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-89244-804-3 review .

- Herbert von One: Michelangelo. English edition, London 1973.

- Martin Weinberger: Michelangelo the sculptor. Volume 1, London, New York 1967.

- Further literature

- Georg Satzinger: Michelangelo's tomb Julius II in S. Pietro in Vincoli. In: Journal for Art History. 64, 2001, pp. 177-222.

- Bram Kampers: The Invention of a Monument. Michelangelo and the metamorphoses of the Julius tomb. In: Horst Bredekamp, Volker Reinhardt (Ed.): Cult of the dead and will to power. Darmstadt 2004, pp. 41-59.

- Horst Bredekamp: End (1545) and beginning (1505) of Michelangelo's Julius grave. Free or wall grave? In: Horst Bredekamp, Volker Reinhardt (Ed.): Cult of the dead and will to power. Darmstadt 2004, pp. 61-83.

- Claudia Echinger-Maurach: Michelangelo's tomb for Pope Julius II. Hirmer, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-7774-4355-3 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Clément, p. 124.

- ↑ Argan / Contardi, p. 13

- ↑ Argan / Contardi, p. 13

- ↑ Verspohl, p. 109.

- ^ Müller, p. 218.

- ↑ Borsi, p. 426.

- ↑ Argan / Contardi, p. 13

- ↑ "... un disegno che aveva fatto per tal sepoltura, ottimo testimonio della virtù di Michelagnolo, che di bellezza e di superbia e di grande ornamento e ricchezza di statue passava ogni antica et imperiale sepoltura."

- ^ David Greve: Status and Statue: Studies on the Life and Work of the Florentine Sculptor Baccio Bandinelli. (= Art, Music and Theater Studies, Volume 4) Verlag Frank & Timme GmbH, 2008, p. 188.

- ↑ Panofsky, p. 561.

- ↑ Grimm, p. 276.

- ↑ Reinhardt, p. 76.

- ↑ Grimm, p. 276.

- ↑ Gardner / Kleiner, p. 469.

- ↑ Argan / Contardi, p. 13

- ↑ Grimm, p. 274.

- ↑ Argan / Contardi, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Grimm, p. 275; von One, p. 41.

- ↑ von Eine, p. 41.

- ↑ Grimm, p. 276.

- ↑ Reinhardt, p. 80.

- ↑ von Eine, p. 44.

- ↑ Grimm, p. 276.

- ^ Romain Rolland: The Extraordinary Life of Michelangelo (Illustrated), Special Edition Books, undated, Chapter 2, p. 1.

- ↑ Argan / Contardi, p. 14

- ↑ Reinhardt, pp. 74 ff.

- ↑ Verspohl, p. 109.

- ↑ Clément, p. 129.

- ↑ von Eine, p. 75.

- ↑ Author ??: Article ?? In: Theological Real Encyclopedia . Study edition Volume 18, Part 2. Catechumenate, Catechumens - Canon Law, de Gruyter, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-11-016295-4 , p. 728.

- ↑ Grimm, p. 404.

- ↑ von Eine, p. 76.

- ↑ von Eine, p. 76 ff.

- ↑ Grimm, p. 404.

- ↑ Panofsky, p. 577; von One, p. 76.

- ↑ von Eine, p. 76.

- ↑ Borsi, p. 426.

- ↑ So z. B. Crispino, p. 90.

- ↑ Gardner / Kleiner, p. 470.

- ↑ Grimm, p. 407.

- ↑ von One, p. 88.

- ↑ Verspohl, p. 114.

- ↑ Thode (p. 216) dates the beginning of work on the four statues to 1519. So also Poeschke, p. 102; so also Crispiano, p. 90.

- ↑ de Tolnay, pp. 55-56; Weinberger, pp. 264-265; Tartuferi, p. 23.

- ^ Crispino, p. 90.

- ↑ Tartuferi, p. 23

- ^ Crispino, p. 90.

- ^ Crispino, p. 90.

- ↑ Verspohl, p. 8.

- ↑ Verspohl, p. 8.

- ↑ Clément, p. 135.

- ↑ Clément, p. 139.

- ^ Müller, p. 218.

- ↑ Borsi, p. 423.

- ↑ Borsi, p. 427.

- ↑ Gardner / Kleiner, p. 470.

- ↑ "questa sola statua è bastante a far onore alla sepoltura di papa Giulio"

- ↑ Müller, p. 219.

- ↑ Verspohl, p. 24.

- ↑ von One, p. 82; Grimm, p. 406.

- ↑ Grimm, p. 404.

- ↑ Grimm, p. 406.

- ↑ von Eine, p. 82.

- ↑ "... alla quale statua non sarà mai cosa moderna alcuna che possa arrivare di bellezza, e delle antiche ancora si può dire il medesimo."

- ↑ Sigmund Freud: The Moses of Michelangelo. In: Imago. Journal of the Application of Psychoanalysis to the Humanities. 3, 1914, pp. 15-36 [1] , here p. 16.

- ↑ Grimm, p. 405.

- ↑ Grimm, pp. 404-405.

- ↑ Müller, p. 219.

- ↑ Gardner / Kleiner, p. 470.

Coordinates: 41 ° 53 ′ 38 " N , 12 ° 29 ′ 35" E