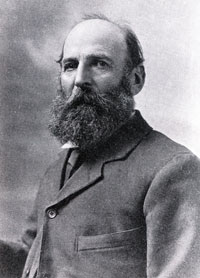

Koos de la Rey

Jacobus Herculaas "Koos" de la Rey (born October 22, 1847 on the farm Doornfontein near Winburg , Orange Free State ; † September 15, 1914 at Langlaierter ) was a Boer general during the Second Boer War . He is considered one of the most capable and bravest military leaders of the Boers during the conflict with the British .

De la Rey was for a long time an outspoken opponent of a military conflict with Great Britain. When he was accused of cowardice for this, he replied that if war broke out, he would still fight if all those who were in favor of war had given up. This should also be the case later.

Early years

Jacobus Herculaas was born as the sixth child of Adrianus Johannes Gijsbertus de la Rey and Adriana Wilhelmina van Rooyen on the family farm Doornfontein near Winburg in the Orange Free State. The family had Dutch, Spanish and Huguenot ancestors , among others . After the farm was confiscated by the British after the Battle of Boomplaats (1848), the de la Reys emigrated to the Transvaal and settled near Lichtenburg . Koos de la Rey received little education as a child. The family later moved again, this time to Kimberley , when diamonds were found there. Here he worked as a transporter.

Family life

De la Rey married Jacoba Elizabeth "Nonnie" Greeff. Together the couple settled briefly on Manana, the Greeff family farm; later they bought the Elandsfontein farm. De la Rey fathered twelve children and also cared for six orphans.

Campaigns

De la Rey took part in the Seqiti war against the Basotho in 1865 and in the war against Sekhukhune in 1876. During the First Boer War in 1880/81 he played a rather minor role, but took over the siege of Potchefstroom as Veldkornet when the commander Piet Cronjé fell ill. He was elected commander of the Lichtenburg district and in 1883 became a member of the Transvaaler Volksraad . He later opposed Paul Kruger and his harsh, xenophobic policies. He warned that this would lead to war with Britain.

Second Boer War

Butcher

- Kraaipan, October 12, 1899

After the outbreak of war, de la Rey became one of Piet Cronjé's field generals. De la Rey led an attack on an armored train of the British at Kraaipan, which fired the first shots of the war. The train derailed and the British gave up after five hours. This event made de la Rey famous, but led to a conflict with Cronjé, who had actually sent him to hinder the advance of enemy troops so that the siege of Kimberley could continue.

- Graspan, November 25, 1899

Lieutenant General Lord Methuen , in command of the British 1st Division, was tasked with ending the Boer siege of Kimberley, and he was moving his troops by rail to Belmont in the Northern Cape Colony . Upon arrival, the British were taken under fire from the Belmont-Koppie by a smaller unit, led by Commander J. Prinsloo. The next morning the British were in position to attack the hill. The Boers withdrew first behind the hill and then as far as Graspan, where they joined forces with the Transvaal and Free State troops under the command of Prinsloo and de la Rey, respectively. The Boers occupied several hills, but were again pushed back by British artillery and infantry. Methuen's units were able to advance to the Modder River, where the Boers had blown up the railway bridge.

- Modder River , November 28, 1899

De la Rey realized that the Boer tactic of occupying hills to attack the enemy from high altitudes left his units helpless in the superior British artillery. Therefore, he ordered that his men and Prinsloos Free Statemen should dig themselves on the banks of the Modder River and the Riet River. The plan was to let the British advance so far that the Boers could take advantage of their rifles while at the same time making it difficult for the British to make use of their artillery. At first the British advanced across the plain without resistance, but then Prinsloo's men began to fire at them from a distance, whereupon the British took cover and filled the Boer trenches with artillery fire; the Freistaatler had to retreat across the river. Only Koos de la Rey's counterattack enabled the Boers to hold positions until sunset when the British withdrew. De la Rey was wounded in this attack and his son Adriaan fell. De la Rey accused Cronjé of not sending reinforcements.

- Magersfontein , December 11, 1899

After the Boer units were driven from the Modder River, the British repaired the destroyed railway bridge and de la Rey had his men dig positions at the foot of the Magersfontein Hill. This tactic proved useful after the hill was taken under intense artillery fire on December 10 with no result. Before sunrise the next day, the Highland regiments advanced in a closed formation. The advance was noticed early by the defenders, however, because the Boers had stretched wires from which tin cans hung, which the British now tripped over. The British units were decimated and after nine hours and heavy casualties, including Commander Andrew Gilbert Wauchope , withdrew in disorder. After this battle, national mourning was ordered in Scotland and Lord Methuen was withdrawn; the liberation of Kimberley was placed in the hands of Lord Roberts .

Defeat of the Boers

The Battle of Magersfontein and the events on the Tugela River were the low points of the British. After that, with massive support from across the empire, they slowly but surely gained the upper hand. At the Battle of Paardeberg , the hapless Piet Cronjé was surrounded by the British and surrendered, while de la Rey organized the resistance against General French's advance at Colesberg in the Cape Colony. The British captured Bloemfontein on March 13, 1900, Pretoria fell on June 5. Paul Kruger, the President of the Transvaal, fled to Portuguese East Africa and eventually Europe.

Guerrilla warfare

Only the hard core of the Boers was willing to keep fighting. De la Rey, Louis Botha and other commanders met at Kroonstad and devised a new guerrilla tactic . The west of the Transvaal was assigned to de la Rey, who carried out small campaigns over the next two years, winning battles at Moedwil, Nooitgedacht, Driefontein, Donkerhoek and other places. At Ysterspruit he inflicted heavy losses on the British in soldiers and equipment and captured enough material to revive the Boer forces. At the battle of Tweebosch he was able to capture large parts of Methuen's rearguard, including Methuen himself. Although de la Rey's men were worn out and often hungry, they rode over large parts of the country, tying tens of thousands of British soldiers. He had a great talent for avoiding fights and many believed that he took advice from the eccentric "prophet" Siener van Rensburg who accompanied him . Despite a few setbacks such as the Battle of Rooiwal in April 1902, the command's approx. 3,000 men remained in the field until the end of the war.

behavior

Koos de la Rey behaved nobly towards his enemies. When he captured large parts of Methuen's army and Methuen himself at Tweebosch, he released the troops again as he had no means to feed them. Even Methuen was released because he was badly wounded in battle and de la Rey believed he would die without medical treatment from British doctors.

peace

Great Britain, especially under Kitchener , countered the Boer guerrillas with scorched earth tactics . The aim was to render everything harmless that the Boers could use to continue the war. Women and children as well as sympathizers and farm workers were sent to concentration camps , farms were burned, crops were destroyed and the soil was salinized. The death rate in the concentration camps was high and an estimated half of the Boer population under 16 died. These cruel tactics gradually weakened the Boer commandos' willingness to fight, since they realized that the price of the war was too high; there was hardly anything left to fight for. On the other hand, the Boers punished black people who they suspected of collaborating with the British.

The British offered peace to the Boers several times, for example in March 1901, but were rejected by Louis Botha. Lord Kitchener then proposed a meeting between him and de la Rey in Klerksdorp on March 11, 1902 , at which the two became friends. This gave de la Rey confidence in the seriousness of the British proposals. Diplomatic efforts eventually led to an agreement to hold peace negotiations in Vereeniging , in which de la Rey participated and pushed for peace. The Treaty of Vereeniging was signed on May 31, 1902. The Boers were ultimately granted self-government (enforced in 1906 in the Transvaal and 1907 in the Orange Free State) and three million pounds of reparations were paid out. In return, they recognized the rule of King Edward VII .

After the war, de la Rey traveled with Botha to Europe and the USA to raise money for impoverished Boers, whose farms had been destroyed by the British during the war. They were welcomed with joy in Flanders . In 1903 he traveled to India and Ceylon , where he persuaded prisoners of war interned there to take an oath of allegiance and return to South Africa. Eventually he returned to his farm to live with his wife Jacoba and his surviving children, who had only roamed the country with a few loyal servants during the war. Jacoba wrote the Oorlog (1903) about these experiences in the book Myne Omzwervingen en Beproevingen Gedurende .

Political career

In 1907 de la Rey was elected to the new Parliament of the Transvaal and became a delegate of the National Convention that led to the Union of South Africa in 1910 . He became a senator and assisted the first Prime Minister Botha in reconciling the Boers and the British. This happened against the resistance of the opposition under Barry Hertzog , who wanted to set up a republican government as soon as possible, refused to cooperate with the British and fueled racism.

In 1914, when white miners protested that blacks were allowed to work in the mines and clashes with the police, de la Rey commanded government forces and the strikes were ended. However, this event left a dangerous atmosphere.

Resistance to participation in the First World War

With the outbreak of World War I , there was a crisis in South Africa. Prime Minister Louis Botha sent troops to attack German South West Africa , what is now Namibia . Many Boers were reluctant to fight for Great Britain against a nation that they had supported in their fight against the British (Germany supplied the Boers, among other things, with Mauser rifles ). De la Rey was asked for assistance. In parliament he advocated the neutrality of the Union and declared that he would be an outspoken opponent of war unless South Africa was attacked. He was convinced by Botha and Jan Smuts, however, not to take any measures to instigate an uprising among the Boers. De la Rey was torn between his loyalty to his brothers in arms (many of whom had defected to the Hertzog faction) and his sense of honor.

death

Meanwhile, Siener van Rensburg attracted many people with his visions in which he saw the world covered with war at the end of the British Empire. On August 2nd, in a speech, he told of a dream in which he saw de la Rey in a float decorated with flowers. There was a cloud number 15 over de la Rey, from which blood rained on de la Rey. Many Boers interpreted this vision as a sign of victory, but Van Rensburg said that it was a vision of death.

On September 15, 1914, an old friend of de la Reys, General Beyers, gave up his post and sent a car to take de la Rey from Johannesburg to Pretoria for consultations . In the evening the two drove to the military base in Potchefstroom , where General Kemp had also resigned. Several police barriers were set up along the way (actually to catch the Foster gang ), but Beyers and de la Rey did not stop the car. In Langlaagt, the police shot the fast moving vehicle and Koos de la Rey was killed by a bullet. Some Boers believed he had been murdered because Beyers said there had been a plan for all senior officers to resign at the same time in protest against South Africa's participation in the World War . However, many could not believe that he had broken his oath of allegiance.

Shortly after de la Rey's funeral, the Maritz Rebellion broke out and Christiaan de Wet , Maritz, Kemp, Beyers and other Boer generals took up arms. However, most of the South African army remained loyal to the government and the rebellion was quickly put down by Botha and Smuts. Because of national reconciliation, the rebels were pardoned two years later.

Honors

- In Lichtenburg, de la Rey's hometown, a statue of him on his horse was erected.

- Delareyville , a small town in the northwestern province of South Africa, was named after him.

- Several streets are named after him in South Africa and the Netherlands.

The song De la Rey

In 2006 interest in Koos de la Rey and his life in South Africa increased. The reason for this was the controversial song De la Rey by Afrikaans singer Bok van Blerk . It is about a Freistaatler whose farm was burned down by the British during the Boer War and whose family was interned. In desperation, he calls for General de la Rey. A discussion broke out about whether the song calls the Boers of today to unity in the fight against any present-day oppression; many young Boers were enthusiastic about the song.

The South African Ministry of Culture was forced to issue a statement on the potentially subversive song text, stating that the song was in danger of being misused by right-wing forces. Nevertheless, the author's right to freedom of expression should be respected. The opposition Democratic Alliance stated that De la Rey did not have half as much anti-subversive potential as the song Umshini wami ("Bring me my machine gun") by ANC chairman Jacob Zuma .

See also

literature

- Steve Lunderstedt: From Belmont to Bloemfontein. Diamond Fields Advertiser, May 2000.

- Bernard Lugan : La guerre des Boers. Perrin 1998, ISBN 2-262-00712-8 .

Visual arts

The picture Portret van Generaal JH ("Koos") de la Rey , created by the Dutch portrait painter Thérèse Schwartze (1852–1918), belongs to the collection of the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam .

Web links

- General Jacobus Hercules de la Rey at the Anglo-Boer War Museum ( Memento from August 5, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- Jacobus Herculaas de la Rey 1847–1914 at SA History (English)

- Battle of Modder River (English)

- Battle of Magersfontein (English)

- Generaal Jacobus Herculaas de la Rey ( Memento from August 18, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) (Afrikaans)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Afrikaans singer stirs up controversy with war song. The Guardian, February 26, 2007, accessed January 9, 2016

- ↑ http://www.geheugenvannederland.nl/?/en/items/WITS01:109371

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rey, Koos de la |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Rey, Jacobus Herculaas de la (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Boer general during the Second Boer War |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 22, 1847 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Farm Doornfontein near Winburg , Orange Free State |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 15, 1914 |

| Place of death | Long lay |