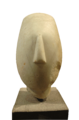

Cycladic idol

Cycladic idols are figures mainly made of marble that date from the Neolithic and the Early Bronze Age . They were found mainly on the Greek archipelago of the Cyclades and are characteristic of the Cycladic culture around 5000 BC. BC to 1600 BC The most pronounced forms are the 3rd millennium BC. Attributed to BC. The production of Cycladic idols ends with the break in the Middle Cycladic Period around 2000 BC. A causal connection with the immigration of Indo-Europeans into the Greek area is discussed. In prehistory and early history, "idol" denotes all abstracted works of art that can be assumed to have a cultic meaning.

Around 230 objects are exhibited in the Goulandris Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens , and the Archaeological Museum in Heraklion on Crete also has an extensive collection . In Germany, the Badisches Landesmuseum in Karlsruhe has an important collection. Smaller collections are in the Louvre , Paris, the British Museum in London, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and various other museums and private collections.

Origin, use and meaning

The material of the figures is predominantly marble from Paros and Naxos , but they were found on various Aegean islands with a focus on the Cyclades, on the Attic mainland and in Asia Minor , which indicates cultural relationships, common customs and religious beliefs throughout the Aegean region suggests that go far beyond mere trade. Various possible uses are discussed: they could have been objects of a ceremonial barter, used as a cultic object, worshiped as an idol, or played a role in funeral rites. The cost of production, the rarity and, last but not least, the aesthetic value suggest that they were valuable personal property and that only a few were given to their owner in the grave. A definitive answer is not possible.

Finds

Cycladic idols have been found in different situations. Since they mostly come from robbery excavations and were distributed via the art trade , their archaeological context is often lost. The undisturbed finds are all the more important.

For a long time, the so-called keros hoard was considered the most important individual find of Cycladic idols. In the early 1960s, or possibly as early as the 1950s, a large number of fragments and some complete figures were acquired from a Greek art dealer based in Paris. Some parts appeared in private collections in the early 1960s, particularly the " Erlenmeyer Collection " in Switzerland, whereupon Christos Doumas carried out a rescue excavation at the presumed site in 1963 and found further fragments of idols and ceramics. By 1968 the complete idols and a substantial proportion of the fragments had been sold to private collectors, but the dealer still held a large number of the fragments. At that point in time, Pat Getz-Preziosi, a doctoral student in archeology, was given unhindered access to this collection for the first time, but her information about the size and the trader's statements about the origin fluctuated in the period that followed. Today her information is considered to have been established, after which all figures that came into private collections via the Parisian dealer come from a robbery in the so-called Kavos field on the south-west side of the now uninhabited island of Keros .

Systematic inspections in the looted area in 1966 and 1967 by a Greek-British team were able to secure an extraordinarily large number of artifacts, architectural traces could not be proven. Further excavations were carried out in 1987/88 by Colin Renfrew and Christos Doumas and in 2006-2008 Renfrew was able to organize another large excavation in Kavos and on the offshore island of Daskalio . This excavation produced the first undisturbed deposit of the Cycladic culture. In addition to 25,000 ceramic shards and almost a thousand shards of marble vessels, 367 clearly identifiable fragments of Cycladic idols were found. All artifacts were intentionally broken, in individual cases even sawed up. Since the fragments of the figures have no common breaking edges apart from two matching parts and the ceramic consists of the clay from different islands, it can be assumed that the destruction took place on the identified islands of Amorgos , Syros , Sifnos and Pano Koufonisi as well as possibly other still unknown parts the broken pieces were brought to Keros for a ritual dumping. Around 25% of the fragments of the Cycladic idols could be assigned to a type, so the depot contains figures from the middle and late Keros-Syros culture . Finds from the previous Grotta Pelos culture could not be verified.

The vast majority of completely preserved Cycladic idols are grave goods . They were mostly found on the island of Naxos in stone box graves of the Grotta Pelos culture . Other finds come from the Keros-Syros culture and western Cycladic islands such as Kea and the grave field of Plastiras in the north of the island of Paros . However, individual finds in a different context, such as in the settlement of Agia Irini on Kea , Phylakopi on Melos , and in particular the finds of various types in the town of Akrotiri on the island of Santorini suggest that they were not specially made for burial purposes.

interpretation

Jürgen Thimme interpreted the lush shapes as references to a fertility symbol , the attitude to a childbearing situation . The use as grave goods and the crouching of the corpses in the grave forms of that time suggests a religion of the cycle, which sees a return to the bosom of an earth and mother goddess in burial. The crossed arms would then indicate a waiting and defensive phase in which the heavily pregnant woman cannot let go and give birth. One interpretation draws a parallel to the Herakles saga, in which Alkmene can only give birth to the hero when Eileithyia sitting with her and Moiren loosen their crossed arms.

Thimmes interpretation is contradicted by Christos Doumas . Rather, he traces the posture with the arms crossed in front of the body to the limits of the material and the processing at the time. Doumas puts the Cycladic idols in the context of other figural grave goods. Possible purposes are a substitute for human sacrifice , the depiction of honored ancestors, guide of the soul of the deceased into the realm of the dead in the sense of a psychopompos , as a companion and service provider of the deceased based on ushabti in ancient Egypt and as apotropaion , magical protection from disaster. As a result, he rejects a purpose specifically for the time after death, after all, no idols were found in the vast majority of graves; there are also no simpler versions.

From the depiction of almost exclusively female forms and the frequent appearance of pregnant figures, Doumas draws conclusions about religious ideas that contain a magical invocation of the goddess to protect against inexplicable threats. In times of danger, the figure is created and consecrated to the goddess. In archaic society, women, and especially pregnant women, are much more often threatened by inexplicable dangers, while the risks for men are more obvious, not directly related to reproduction and therefore do not need magical protection. During its lifetime the figure is kept in the household and used in rituals. Occasionally a figure will break, be repaired or not. At death the figure is charged with magical power and has to go to the grave under a stone slab to protect the living.

The few male figures are almost all depicted in special actions that range from making music to offering a cup to reaching for a dagger. He suggests seeing the male idols as magicians .

Colin Renfrew put together the various interpretations and references in the original find situations and comes to the conclusion that these are cult figures that were used in life, the occasional burial of the deceased being one of the rituals associated with the cult. He interprets the special forms of seated figures as objects in a shrine , altar or similar situation, the more common recumbent idols as votive offerings or personal representatives of a cult follower. In the case of the rare large figures, he discusses the use in a public place, but limits this due to the find situation in graves, from which he assumes a close bond with an owner despite the public use. In all explanations, he attaches importance to the fact that all interpretations are to be considered speculative.

Due to the relative rarity of marble figures in the tombs of the early Cycladic culture, it was discussed that marble was possibly only accessible to a few people, that the majority had to be content with simpler material and that the assumed figures made of perishable materials such as wood have not been preserved. So if a much larger number of figures and use by everyone can be assumed, then it could be the remains of shrines in which figures of goddesses and those of worshipers were kept. Damage would then indicate that the figures were used in rituals. The large majority of female figures would represent a special role for women in early Cycladic society as the origin of life. This is contradicted by the fact that the obvious material terracotta is known in one case from the end of the Neolithic, but was completely unknown at the time of the wedding of the Cycladic figures.

development

predecessor

The canonical idols of the early Bronze Age of the Spedos type and its neighbors still have two very different predecessors in the Neolithic (for chronological classification see: Cycladic culture ) .

Small, abstract figures, whose shape is only reminiscent of people to a limited extent, serve as a model. They are mostly only between five and a little over ten centimeters and are differentiated according to the shoulder and violin type. The former consists of a stylized shoulder area with a neck. The latter comes closer to a female figure, with a neckline and a body marked by a waist. In some cases the arms are indicated by incisions. They are made of marble or ceramic material and have been found on the islands of the Cyclades as well as on mainland Greece and Asia Minor. Jürgen Thimme derives them from found natural stones, especially those found on the beach and abraded by the sea. Because of the find situation, together with sea-related grave goods, he sees them as a sea deity, which he equates with the “Great Goddess” (see: Mother Archetype ) . Finds from the 1990s in Akrotiri confirm this thesis, since worked idols of this type were found together with completely unworked natural stones of a comparable shape.

The other model are Anatolian figures of crouching or crouching women with lush shapes, in which the crossed arms appear for the first time, which are typical of the later Cycladic idols.

More recent finds of naturalistic heads made of terracotta from the end of the Neolithic from the settlement of Kephala on Kea could represent another line of tradition.

Canonical idols

In the Grotta Pelos culture from 3000 BC Direct precursors of the canonical idols appear for the first time. They already have the schematized faces in which only the elongated nose emerges, and their legs appear separated by a notch. The finds from this period were often damaged and repaired during production or shortly afterwards, as the artists did not yet have sufficient experience of which shapes are sufficiently stable. They are based on the Plastirastyp and Lourostyp distinguished. The second is more stylized, the body shapes appear drawn out of the material. Some specimens that have transitional forms to the following types are grouped together as pre-canonical idols .

With the Keros-Syros culture of the Early Cycladic II period (around 2500 BC) the typical basic form was achieved. It is called canonical because the proportions of the figures are constant within the different types. Most of the finds are from this period. The size of the figures varies from only around 10 cm to around 50 cm. One figure with 89 cm and one with 148 cm are exceptionally tall. In addition, several near-life-size heads have been found, and it is not known whether they ever belonged to full bodies. Typical are 20–35 cm. According to the sites and the stylistic features, four main forms are distinguished, the periodization of which was made by Colin Renfrew in the 1960s. Accordingly, the capsule type is to be regarded as the first in time, the Spedo type and the Dokathismata type as simultaneous and the Chalandrian type as a conclusion. At the same time, the Koumasa type with flat, closed forms, which was only found in Crete, deviates significantly .

Idol of the early "Spedo type" , 88.8 cm, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

The capsule-type idols have a round plastic shape on all parts, the head is rather plump, the breasts are clear and set far apart. The shoulders are round and only slightly wider than the hips. Due to the slightly drawn-up knee joints, the figures are clearly marked as lying. No idol of this type has a carved pubic triangle.

The most common finds are of the Spedo type . It is characterized by rounded shapes with a thick head. The cheeks are the widest part of it, the parting usually looks cut off horizontally. The straight shoulders with a narrow waist result in a trapezoidal upper body. The thighs are again wider than the waist. Only a few large figures of this type have a pubic triangle incised. Pregnant women are relatively common.

The simultaneous docathismata type is characterized by an elegant combination of geometric and curved shapes. While the upper body looks like it was constructed with a ruler, the neck and head are elongated and the head shape diverges towards the top. The breasts are small and set wide apart, almost all figures of this shape have an incised pubic triangle.

The latest Chalandrian type is characterized by hard geometric shapes. The chest is almost square, the shoulders very straight and the widest part of the figure. From them to the narrow feet, the outline of the idol forms a triangle. The strongly stylized head is also triangular.

The Koumasa-type Cretan figures are small in size, with a geometric outline and a flat surface. This makes them look very stylized. They are considered a Minoan imitation of the Cycladic idols; Due to the great similarity with the Dokathismata and Chalandrian types, a rather late date of origin is assumed.

Post-canonical figures

With the Kastri culture at the end of the Early Cycladic II period or the beginning of Early Cycladic III around 2200 BC. The strict forms of canonical time are dissolved. The arm position is varied, sometimes one arm reaches diagonally across the upper body while the other lies horizontally. The arms are sometimes no longer crossed, but the hands touch each other in front of the chest, as in some pre-canonical styles. The materials used are also becoming more diverse. In addition to marble and a black stone, two figures made of one metal, here made of lead , are known for the first time from this period .

Special forms

Aulos and harp player , National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Very few Cycladic figures deviate from the typical pattern of the standing or straight female figure. A few characters are male. The artistic highlight, however, are the exceptional groups of figures or figures in special activities. They are all attributed to canonical time and the type of Spedo.

reception

The first Cycladic figures were found around the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. Only a few enjoyed the appreciation of the art world of that time. The two harpists shown above from the island of Santorin found their way into the collection of the Grand Duke of Baden, Frederick I , as early as 1853 , but at that time the traditional figures were still considered "clumsy first works of round sculpture in stone". Another verdict was: "We do not like to cite those small [...] monsters made of marble fragments that have been found in various places, especially on the islands."

This only changed with the advent of abstract art in the 20th century. The Cycladic idols have been rediscovered: "Technically and stylistically, the Cycladic works surprise with the choice of the noble material and the reliability of its processing, the refined and masterful structure of spatial structures" and "eminently plastic character".

Artists who felt committed to modernity took up the prehistoric imagery and created works in the tradition of the Cycladic idols. Hans Arp traveled to Greece and studied the Cycladic culture on site. Also Constantin Brancusi was based on his sculptures at the rediscovered role models.

Since the 1960s, the appreciation of the Cycladic idols had developed so far that forgeries appeared on the international art markets. Museums and private collectors paid up to DM 100,000 for a figure. In addition, numerous robbery excavations took place on all islands . The market initially collapsed after the forgeries were discovered, and the illegal excavations also subsided as a result. In 1970, UNESCO took action against the stealing of antiquities with the UNESCO Convention on Measures to Prohibit and Prevent the Inadmissible Import, Export and Transfer of Cultural Property .

At the same time, scientific research into the figures reached a climax. In 1976 the exhibition Art and Culture of the Cyclades Islands in the 3rd millennium BC in the Badisches Landesmuseum in Karlsruhe was decisive . In preparation for the exhibition, publications from a wide variety of disciplines, from archeology and art history to geology and geography , were compiled. The exhibition was strongly characterized by objects from robbery excavations, which is why the Greek collections did not provide any exhibits. In return, objects came from almost all of the major museums in the western world and from many private collectors who had acquired items on the art market from black sources. The catalog lists 581 exhibits and is still the best compilation of Greek art from the Bronze Age.

The most important individual collection of Cycladic idols was brought together by the Greek shipowner Nicholas Goulandris and his wife Dolly. The art collectors had made it their particular task to dry out the black market, which is why there are many pieces in this inventory that are attributed to the Keros hoard . The collection was first made available to the public in 1978 and was exhibited in parts in Washington, DC , Tokyo and London from 1979 to 1984 . Since 1986 it has been the core of the Goulandris Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens.

In the following decades the art market continued to expand. In 2010, a Spedos-type Cycladic diol from a Swiss private collection at Christie's in New York reached a price of $ 16,882,500. On the other hand, the understanding of restitution claims grew. When the Badisches Landesmuseum prepared another Cyclades exhibition for 2011, the Greek museums again refused all requested loans and Greece demanded the return of objects from robbery excavations. In June 2014 the Badisches Landesmuseum returned a female Cycladic idol and a handle made of chlorite slate to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

literature

- Marie-Louise and Hans Erlenmeyer : From the early pictorial art of the Cyclades . In: Antike Kunst 8, 1965, issue 2, pp. 59–71.

- Jürgen Thimme : The religious significance of the Cycladic idols. In: Antike Kunst 8, 1965, issue 2, pp. 72–86.

- Christos Doumas : The NV Goulandris Collection of Early Cycladic Art . New York, Praeger 1969.

- Colin Renfrew : The Development and Chronology of the Early Cycladic Figurines . In: American Journal of Archeology 73, 1969, pp. 1-32. ( JSTOR 503370 )

- Jürgen Thimme (Hrsg.): Art and culture of the Cyclades islands in the 3rd millennium before Christ. Exhibition […] in Karlsruhe Palace from June 25th - October 10th 1976. Müller, Karlsruhe 1976. ISBN 3-7880-9568-7

- Pat Getz-Preziosi: Early Cycladic Sculpture. An Introduction . J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu 1985. ISBN 0-89236-101-8

- Pat Getz-Preziosi: Sculptors of the Cyclades. Individual and tradition in the third millennium BC University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 1987. ISBN 0-472-10067-X

- Pat Getz-Preziosi: Early Cycladic Art in North American Collections . Richmond 1987. ISBN 0-295-96553-3 ; ISBN 0-295-96552-5

- J. Leslie Fitton: Cycladic Art . British Museum Press, London 1989, ISBN 0-7141-1293-3 .

Web links

- Andrea Vianello: Cycladic figurines in funerary rituals (PDF; 156 kB) on bronzeage.org.uk, 1999 (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Doumas, p. 81.

- ^ Bernhard Maier: Idols, idolatry. § 2 Aspects of religious studies. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 15, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2000, ISBN 3-11-016649-6 , p. 329.

- ^ Vianello (with further references).

- ↑ Peggy Sotirakopoulou: The Keros Hoard - Some Further Discussion . In: American Journal of Archeology 112, 2008, pp. 279-294.

- ↑ Pat Getz-Gentle (former name: Pat Getz-Preziosi): The Keros Hoard Revisited . In: American Journal of Archeology 112, 2008, pp. 299-305.

- ↑ Colin Renfrew et al .: Keros - Dhaskelion and Kavos, Early Cykladic Stronghold and Ritual Center. Preliminary Report of the 2006 and 2007 Excavation Seasons . In: The Annual of the British School at Athens 102, 2007, pp. 103-136.

- ↑ Jack L. Davis: A Cycladic figure in Chicago and the non-funeral use of Cykladic marble figures . In: Fitton 1989, pp. 15-21.

- ↑ Thimme p. 74.

- ↑ Thimme p. 80.

- ↑ a b Doumas pp. 88-89.

- ^ Doumas p. 93.

- ↑ Doumas p. 94.

- ↑ Colin Renfrew in: Fitton 1989, pp. 24-31.

- ↑ a b R. LN Barber: Early Cycladic Marble Figures - Some Thoughts on Function. In: Fitton 1989, pp. 10-14.

- ^ RLN Barber's contribution to the discussion in: Fitton 1989, p. 35.

- ↑ Thimme p. 82.

- ↑ Panayiota Sotirakopoulou: The Early Bronze Age Stone Figurines From Akrotiri on Thera and Their Significance for the Early Cycladic Settlement . In: The Annual of the British School of Athens 93, 1998, pp. 107-165.

- ↑ Art and Culture of the Cyclades Islands p. 452.

- ↑ All descriptions based on the art and culture of the Cyclades Islands , 1976.

- ↑ Arthur Milchhoefer : The beginnings of art in Greece . Leipzig 1883, p. 142 .

- ^ Johannes Overbeck : History of the Greek sculpture . Volume 1, Leipzig 1857 p. 41 .

- ^ Karl Schefold : Masterpieces of Greek Art . B. Schwabe, Basel 1960, p. 2.

- ↑ Josef Riederer, Forgeries of marble idols and vessels of the Cycladic culture , in: Art and Culture of the Cyclades Islands , 1976, pp. 94–96.

- ↑ Josef Riederer: The tricks of the counterfeiters , in: Zeitschrift Bild der Wissenschaft, issue 11/1978, page 70

- ^ Goulandris Museum of Cycladic Art: History (English).

- ↑ Christie's: A cycladic marble reclining female figure , Sale 2364, December 9, 2010, lot 88.

- ^ Badisches Landesmuseum: Cyclades - Living Worlds of an Early Greek Culture , December 17, 2011 to April 22, 2012.

- ↑ Press release: Return of looted grave art to the Greek Ministry of Science, Research and Art, Baden-Württemberg, June 6, 2014.