Loïe Fuller

Loïe Fuller , née Marie Louise Fuller (born January 15, 1862 in Fullersburg , Illinois , † January 1, 1928 in Paris ) was an American dancer, serpentine dancer and inventor. She was a pioneer of modern dance and light plays on stage.

biography

Before she began her career as a dancer and choreographer , she worked as an actress and singer in numerous burlesques, farces and operettas from 1878 to 1891 , among others. a. in the Nat Goodwin productions Little Sheppard , Turned Up (1886) and The Big Poney Of The Gentlemanly Savage (1887). In Alfred Thompson's The Arabian Nights , she played the role of Aladdin . In 1882/83 she played banjo in Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show .

She first appeared as a serpentine dancer in Rud Aronson's Casino Company . Her dance was first seen as a divertissement in the second act of Edmond Audran's operetta Uncle Celestine .

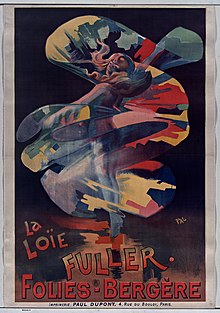

After performances in Boston and Brooklyn , the production came to New York at the Casino Theater on February 15, 1892 . On the advice of the conductor Hugo Sohmers , she decided to go to Paris . Before that she accepted an engagement in the Berlin Wintergarten . Only in Paris did she make her decisive breakthrough. On December 5, 1892, she made her sensational debut in the Folies Bergère with the dances La Serpentin , La Violette , Le Papillon and XXXX (which she later called La Danse Blanche ) . She appeared in the "Folies Bergère" until 1899.

In 1893 she patented her serpentine dance costume and “stage devices for creating illusion effects” in Paris and London . With her productions she enthused and inspired many artists, u. a. Will Bradley , Jules Chéret , Maurice Denis , Thomas Theodor Heine , Auguste Rodin , Stéphane Mallarmé , James McNeill Whistler and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec , who they immortalized in their works of art. She was the first to work with colored light projections and electric light. The sculptor François-Raoul Larche created table lamps in the form of a sculpture of the dancer, the electric lighting is hidden under her veil.

Gabriel Pierné wrote the music for Fuller's interpretation of Salomé in 1895, which was premiered on March 4, 1895 in the Comédie Parisienne as a lyric pantomime by Charles H. Meltzer and Armand Silvestre - Richard Strauss did not complete the opera of the same name until more than ten years later. In the same year, the dances La Nuit , Le Firmament , Le Lys du Bil and Le Feu , which she performed in the Music Hall of Serge Koster and Albert Bial in 1896 during an American tour .

Further tours took her to southern Europe and South America. The architect Henri Sauvage built a theater pavilion for Fuller on the occasion of the Paris World Exhibition in 1900 . As a sponsor of Isadora Duncan , Maud Allan , Sada Yacco and Hanako , she organized numerous touring performances.

From 1902 she also performed with a group of young dancers. In March 1903 she showed works by Auguste Rodin at the National Arts Club together with her private collection . The following year she created her Radium Dance with fluorescent effects. The music for Fuller's second production of Salomé of Robert d'Humière's La Tragédie de Salomé came from Florent Schmitt . The first performance took place on November 9, 1907 in the Théâtre des Arts .

In 1908 her autobiography Quinze ans de ma vie (French: 15 years of my life ) was published. As a result, she created numerous ballets a.o. for her company. a. on Mozart's Le Petits Riens , Debussy's Nocturnes and Stravinsky's Feu d'artifice . Le Lys de la vie was based on a fairy tale by Carmen Sylva (stage name of Queen Marie of Romania ), which Loïe Fuller also filmed. She also worked on the films Visions des rêves (French: Visions of Dreams ) and Coppelius and the Sandman ; the latter, however, remained unfinished.

Loïe Fuller died on January 1, 1928 in Paris at the age of almost 66.

When you consider that she never had any dance training or anything like that, her contribution to stage reform is all the more remarkable. With her inventions she made a great contribution to the stage at the beginning of the 20th century. Through her abstract dance she paved the way for modern dance .

Choreographies and productions (chronological)

- Serpentine Dance : solo choreography; Premiered on February 29, 1892; Madison Square Theater, New York; Music: Érnest Gillet

- Le papillon : solo choreography; Premiered November 5, 1892; Folies Bergère , Paris

- La fleur : solo choreography; Premiered on August 26, 1893; Garden Theater, New York

- Salome : lyric pantomime; Premiered March 4, 1895; Comédie-Parisienne, Paris; Music: Gabriel Pierné

- La nuit : solo choreography; Premiered March 6, 1896; Koster and Bial's Music Hall, New York

- La danse du feu : solo choreography; Premiered September 14, 1897; Folies-Bergère , Paris; Music: Richard Wagner

- Le lys : solo choreography; Premiered September 14, 1897; Folies Bergère , Paris

- La danse des fleurs : solo choreography; Premiere in May 1898; Private event at 24 rue Cortambert, Paris

- La tempete : solo choreography; Premiered September 14, 1901; Théâtre de l'Athenée, Paris

- La tragedie de Salome : tragic pantomime in two acts; Premiered November 9, 1907; Théâtre des Arts, Paris; Music: Florent Schmitt

- Une nuit sur le monte chauve : group choreography; Premiered on December 13, 1913; Théâtre national de l'Odéon , Paris; Music: Modest Mussorgsky

- Les mille et une nuit : group choreography; ; Premiered on December 13, 1913; Théâtre national de l'Odéon , Paris; Music: Armande de Polinac

- Le lys de la vie: fairytale staging; Premiered July 1, 1920; Théâtre de l'Opéra de Paris ; Music: Claude Debussy , Edvard Grieg , Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy , Nikolai Rimski-Korsakow , Armande de Polinac, Edward MacDowell , Modest Mussorgski , Peter Tschaikowski

- Copelius and the Sandman : fairy tale production with the collaboration of Gabriele Sorère; Premiered on December 4, 1925; Théâtre des Champs-Elysées , Paris; Music: Arthur Honegger

Film projects (chronological)

- Le lys de la vie (1920/21)

- Visions des rêves (1924/25)

- Copelius and the Sandman (1927/28, unfinished)

Film adaptations

In 2016, her career in the biopic The Dancer was filmed with the French singer Soko in the lead role.

Other reception

On her Reputation Stadium tour in 2018, American singer Taylor Swift dedicated a performance to Loïe Fuller in each show.

Primary literature

- Ma vie et la danse. Autobiography. L'œil d'or, Paris 2002, ISBN 2-913661-04-1 .

Secondary literature

- Ann Cooper Albright: Traces of Light. Absence and Presence in the Work of Loïe Fuller . Wesleyan University Press, Middletown / Connecticut 2007, ISBN 0-8195-6843-0 .

- Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker (Ed.): Loïe Fuller, danced Art Nouveau. Prestel, Munich et al. 1995, ISBN 3-7913-1631-1 .

- Gabriele Brandstetter : “La Destruction fut ma Beatrice” - Between modern and postmodern: Loie Fuller's dance and its effect on theater and literature . In: Erika Fischer-Lichte / Klaus Schwind (eds.): Avantgarde and Postmoderne. Processes of structural and functional changes . Stauffenburg-Verlag, Tübingen 1991, pp. 191-208, ISBN 3-923721-498 .

- Gabriele Brandstetter , Brygida Maria Ochaim : Loïe Fuller. Dance, play of light, Art Nouveau. Rombach, Freiburg (Breisgau) 1989, ISBN 3-7930-9052-3 .

- Richard Nelson Current, Marcia Ewing Current: Loie Fuller, goddess of light. Northeastern University Press, Boston MA 1997, ISBN 1-55553-309-4 .

- Renate Flagmeier: Loie Fuller. Making the invisible visible . In: Staatliche Kunsthalle Berlin , NGBK (Hrsg.): Being absolutely modern: Between bicycle and assembly line. Culture technique in France 1889-1937 . Exhibition catalog Staatliche Kunsthalle Berlin / NGBK. Elefanten Press, Berlin 1986, pp. 179-189, ISBN 3-88520-180-1 .

- Rhonda K. Garelick: Electric Salome. Loie Fuller's Performance of Modernism . Princeton University Press, Princeton 2007, ISBN 0-6911-4109-6 .

- Rhonda K. Garelick: Electric Salome. Loie Fuller at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 . In: Ellen J. Gainor (Ed.): Imperialism and Theater. Essays on World Theater, Drama, and Performance. 1795-1995 . Routledge, London / New York 1995, pp. 85-103, ISBN 0-4151-0641-9 .

- Giovanni Lista: Loïe Fuller. Danseuse de la Belle Époque. Stock et al., Paris 1995, ISBN 2-234-04447-2 .

- Sandra Meinzenbach: "To impress an idea I endeavor" - Loïe Fuller. In: dies .: New old femininity. Images of women and art concepts in free dance: Loïe Fuller, Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis between 1891 and 1934 . Tectum, Marburg 2010, pp. 59-134, ISBN 978-3-8288-2077-7 .

- Brygida Maria Ochaim: Loie Fuller's Temple of Light . In: Friedrich Berlin Verlagsgesellschaft (ed.): Ballettanz . 6/2004, pp. 35-37.

- Brygida Maria Ochaim: Loie Fuller. The soloist of the dancing color . In: dance drama . 2nd quarter / 1988; No. 3, pp. 22-24.

- Brygida Maria Ochaim: La Loie Fuller: light and shadow, impulses for a new style of movement . In: Ballett-Journal / Das Tanzarchiv. Newspaper for dance education and ballet theater . 34th year; No. 1/1. February 1986, pp. 52-59.

- Brygida M. Ochaim, Claudia Balk: Variety dancers around 1900. From sensual intoxication to modern dance. Stroemfeld, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1998, ISBN 3-87877-745-0 .

- Sally R. Sommer: Loie Fuller's Art of Music and Light . In: Dance Chronicle. Studies in Dance and the Related Arts . No. 4/1981, pp. 389-401.

Web links

- Loie Fuller at the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Petra Bahr: L oie Fuller. Border crosser of the dance aesthetic . In: Tà katoptrizómena. Magazine for theology and aesthetics , 1st year, issue 2/1999.

- "La Loie" as pre-cinematic performance - Descriptive Continuity of Movement (Engl.)

- Loïe Fuller. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

- Claudina: Movement and Metamorphosis - Danced Veil Sculptures , Halima Trade Journal, 2/2015, ISSN 0938-0620 Online version of the specialist article

Individual evidence

- ↑ The dancer as a table lamp

- ↑ Ellie Bate: 13 Seriously Impressive Facts You Probably Didn't Know About Taylor Swift's Reputation Tour ( English ) buzzfeed.com. June 19, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Fuller, Loïe |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Fuller, Marie Louise |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American burlesque actress, singer, serpentine dancer, inventor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 15, 1862 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Fullersburg , Illinois |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 1, 1928 |

| Place of death | Paris |