Mary Toft

Mary Toft , occasionally also Tofts , née Denyer (* baptized February 21, 1703 in Godalming , † January 1763 , buried January 13, 1763 in Godalming), was a maid from Godalming, Surrey , England . She gained fame in 1726 for allegedly giving birth to rabbits . This triggered an extensive scientific and public controversy and an enormous interest among the population, especially a broad response in the newspaper landscape and periodical press, which was still young in the 18th century .

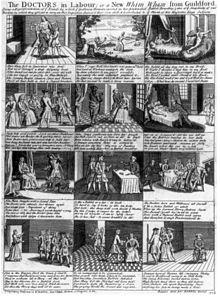

Although the case was resolved comparatively quickly, taking into account the knowledge of the time, the fraud affair ruined the careers of several prominent scholars. They were exposed to public scorn and ridicule for their gullibility. The event was the talk of the country for weeks and the subject of countless newspaper and magazine articles, caricatures and pamphlets . Toft and her rabbits had attracted public interest not only because of the large number of scientific texts published about their case, but also because of the tremendous media coverage and the abundance of literary and artistic reactions to the alleged rabbit births. The affair was many times in contemporary cartoons satirizing , not least by the English artist and social critic William Hogarth , who mocked in his satirical images doctors frequently than quacks and its engravings in Germany Georg Christoph Lichtenberg commented. Whether it was a poem, a play or a drawing, there was hardly an art movement that the "rabbit woman" - as the vernacular called her - did not have as its topic.

“The medical profession has never been so ridiculed in the eyes of the public as it was on the occasion of this affair,” says a specialist article by the London gynecologist SA Seligman from 1961.

Even until recently the case has consistently been the subject of scientific, if not medical or gynecological, treatises, and in 2005 it was worth reporting by the BBC that began with the words:

"There were several notable events in England in 1726: George Frideric Handel became a British subject, Jonathan Swift published Gulliver's Travels , and Mary Toft gave birth to at least 17 'preternatural' rabbits."

"There were several notable events in England in 1726: George Frideric Handel became a British citizen, Jonathan Swift published Gulliver's Travels, and Mary Toft gave birth to at least 17 'supernatural' rabbits."

Legend

The London Weekly Journal published the following article on November 19, 1726:

"From Guildford comes a strange but well-attested piece of news. That a poor Woman who lives at Godalmin, near that Town, was about a Month past delivered by Mr John Howard, an Eminent Surgeon and Man-Midwife, of a creature resembling a Rabbit but whose Heart and Lungs grew without [outside] its Belly , about 14 Days since she was delivered by the same Person, of a perfect Rabbit: and in a few Days after of 4 more; and on Friday, Saturday, Sunday, the 4th, 5th, and 6th instant, of one in each day: in all nine, they died all in bringing into the World. The woman hath made Oath, that two Months ago, being working in a Field with other Women, they put up a Rabbit, who running from them, they pursued it, but to no Purpose: This created in her such a Longing to it, that she (being with Child) was taken ill and miscarried, and from that Time she hath not been able to avoid thinking of Rabbits. People after all, differ much in their Opinion about this Matter, some looking upon them as great Curiosities, fit to be presented to the Royal Society, etc. others are angry at the Account, and say, that if it be a Fact, a Veil should be drawn over it, as an Imperfection in human Nature. "

“Strange but well-documented news reaches us from Guildford that a poor woman who lives in Godalmin, near this town, about a month ago from Mr. John Howard, an eminent surgeon and obstetrician, was of a creature like one Rabbits with hearts and lungs that grew outside the abdomen about 14 days after giving birth to a whole rabbit. In the following days she gave birth to another 4, on Friday, Saturday, Sunday the fourth, fifth and sixth, one each day for a total of nine. They were all stillborn. The woman affirmed that two months earlier she and other women had caught a rabbit while working in the field for no particular reason. This made her crave rabbit meat so much that she fell ill and miscarried, and from that moment on could not stop thinking about rabbits. The judgments of this case are very different from one person to the other, some regard it as a curiosity to be presented to the Royal Society, others are angry and believe that if the story is actually true, it would be better to cast a veil of oblivion on this imperfection human nature. "

The poor woman was Mary Toft, who quickly became a national celebrity with this story. The news spread rapidly, especially through the young newspaper industry with its various daily newspapers and weeklies, and found so much faith that soon hardly anyone wanted to eat rabbits anymore - the whole of England was afraid of finding a product by "rabbit breeder" Mary Toft on their plates . Even if some papers saw the story more critically than the Weekly Journal - rabbit ragout and hare pepper were removed from the menu and many doctors felt compelled to form their own judgment of what was going on.

biography

Mary Toft was baptized as Mary Denyer on February 21, 1703. The daughter of John and Jane Denyer grew up in poor conditions in Godalming, was illiterate and hired herself as a maid with field work. 1720 she married the equally destitute clothier -Gesellen Joshua Toft; the couple had three children, Mary, Anne and James.

As was common among the poor rural population of the 18th century, Toft had to continue working in the fields when she became pregnant again in 1726. At work and to her neighbor Mary Gill, she complained of painful complications. On September 27, 1726, with the help of the neighbor and her mother-in-law, midwife Ann Toft, she suffered a miscarriage , but continued to go into labor and feel pregnant . The miscarriage turned out to be a dead rabbit.

John Howard, a summoned surgeon and obstetrician from Guildford , gave birth to several other rabbits, but his patient remained "pregnant". The animals had all been stillborn, and pieces of rabbits much more likely than whole rabbits, but this didn’t detract from the doctor’s enthusiasm for this medical sensation. He explained that these were individual parts by the particularly powerful contractions of her uterus , which would have torn the animals apart. In the following days he noted that he had given birth to the "pregnant woman" from a rabbit's head, cat paws and other parts of the animal's body and, in a single day, from nine dead rabbit fetuses .

Howard sent letters to England's most famous doctors telling them about these miraculous births. He also informed the King's Secretariat and John Ker, the Duke of Roxburghe , urging that other men of science help him further study this bizarre phenomenon.

As a result, Toft was examined by countless doctors, obstetricians and scientists and brought before a number of members of the London Society, among them the Swiss personal physician to King Nathaniel St. André and the astronomer Samuel Molyneux , secretary to the heir to the throne and Prince of Wales Georg August , who the King George I had personally sent curious and curiosities .

The imagination of the urban and rural population was unleashed, the news spread nationwide via press reports, the case was hotly debated in all social circles, especially since it suddenly became possible to talk about the taboo topic of the female body including the uterus , vagina or vulva entirely to be able to discuss freely and openly.

However, on December 4, the scam was exposed, especially since it was discovered that Mary Toft's husband had been buying rabbits all the time lately. A few days later, the fraudster confessed to having introduced rabbit parts herself in order to fake the births. It was transferred to Bridewell Prison in London , where its guards continued to display it to a wide audience for a fee. After spending a few months in prison, charges against her were dropped and she was released from custody - certainly not for lack of evidence, but obviously because of the further embarrassment that would have arisen for the large number of people involved in a public trial . Since she had made various confessions and different statements, the exact circumstances of the case and who else was involved were never established.

As a result, Mary Toft largely disappeared from the public eye, as quickly as she had appeared a few months earlier. The media interest in her person was flagged. Only the Duke of Richmond , who had a residence near Godalming, occasionally presented them as a curiosity at societies in the following years. Nonetheless, science as well as art and culture continued to deal with the case for centuries.

On April 19, 1740, Mary Toft had another footnote in the Weekly Miscellany :

"The celebrated Rabbit-woman of Godalmin was committed to Guildford Gaol for receiving stolen goods."

"The famous Godalmin Rabbit Woman was admitted to Guildford Prison for stolen goods."

The circumstances of this incident, which again brought her into conflict with the law, have not survived, nor are any details about her future life. Almost 30 years later, the Daily Advertiser notes on January 21, 1763:

"Last week died, at Godalmin, in Surry, Mary Tofts, formerly noted for an imposition of breeding rabbits."

"Last week, Mary Tofts, known for giving birth to breeding rabbits, died in Godalmin, Surrey."

According to information in the church register of Godalming, she was buried there after her death on January 13, 1763.

Medical research and scientific publications

After John Howard had corresponded with the royal diplomat Henry Davenant since November 4th, St. André and Molyneux were the first experts to arrive in Guildford on November 15th, where Howard has now taken his patient to an inn for better accessibility would have. St. André examined the woman and examined the other rabbit parts that she gave birth while he was there.

When asked, Mary Toft said that at the beginning of her pregnancy she had observed a rabbit working in the fields and tried in vain to catch it, which subsequently led to a massive craving for fried rabbit meat. As a result, she has recently caught rabbits or bought them at the market to eat them. She also reported on dreams in which rabbits played a role. St. André then explained the births as an effect of the maternal impression, which, according to part of the science of the time, had a direct effect on the formation of the fetus and could cause deformities. Obviously, this desire had an uncanny influence on their reproductive organs. There is no doubt that the woman is telling the truth and that it is a sensational medical finding.

Molyneux and St. André took samples of the rabbits and set out to report to the king. Fascinated by this scientific sensation, the king also sent his German personal physician, the surgeon Cyriacus Ahlers , to Guildford. He reached the scene on November 20 and found Toft with no signs of pregnancy. He expressed his first doubts among colleagues and reported on his observations that Toft pressed her knees and thighs together as if she wanted to prevent something from "falling off". Likewise, Howard's behavior when he refused to allow him to help with the delivery seemed suspicious. Convinced it was a rip-off, he took some samples of the animal carcasses and returned to London on some pretext. Upon closer inspection of the samples taken, he found that the parts had been cut with an instrument and not torn; He also found animal droppings , straw and grain remains adhering to them .

On November 20, 1726, Ahlers judged in his report: “ Tending to prove her extraordinary deliveries to be a cheat and imposture. "(German:" Your extraordinary deliveries should tend to turn out to be fraud and imposture. ")

On November 26, 1726, St. André held an anatomical demonstration in London in the presence of the king and the heir to the throne to present his view of things, to explain the "medical sensation" and to refute Ahlers' statements. followed by the publication of a font. During the medical examination, he had primarily dealt with the anatomy of the individual parts of the rabbit delivered, the examination of which would have led to the result that they were undoubtedly of "supernatural origin". This report is dated November 28, 1726 and contains affidavits by Howard, Molyneux, Toft and a landlady who were supposed to refute Ahlers' representations. The writing did not appear until December 3rd or 4th, just as the fraud was already apparent.

On November 28th, Sir Richard Manningham , London's most famous obstetrician and member of the Royal Society , arrived at Mary Toft's bedside. In his presence she was released from a piece of tissue he identified as a pig's bladder; St. André and Howard, on the other hand, described it as a chorion , the outer layer of the pericarp of a fetus . Manningham was puzzled, especially since the allegedly delivered piece smelled strongly of urine. According to his report published on December 8th, he examined Toft himself gynecologically according to the medical standard of the time, that is, he examined her chest and felt the abdomen not only externally or over blankets or items of clothing, but also examined the abdominal wall, vagina and cervix with his hands and determined the dimensions and condition of the fallopian tubes and uterus . He noted that a small amount of fluid had leaked from one breast and that the cervix appeared to be somewhat elongated, but the cervix was hard and almost closed, and during the entire examination he could not feel any movements that would suggest a fetus. After all this, he was convinced that the part of the tissue that had been delivered “ never came out of her uterus ” (German: “ never came out of her uterus ”). He also noted that he had been convinced of a fraud from that moment on, but wanted to determine the full extent before uncovering it, especially since St. André vehemently insisted on having carried out identical examinations himself and swearing that each pieces of rabbit delivered from her uterus came out of her uterus.

Which of the medical professionals followed Howard and St. André's convictions, both ultimately honorable doctors who had made affidavits, or who were convinced from the outset that Toft was a fraud, cannot be reconstructed in detail. Their publications sometimes differ from one another in terms of content or were later partially relativized. After the fraud became known, some scientists were evidently anxious to deny certain previous positions, to reinterpret statements or to deny statements in order to avert harm to themselves and their careers.

Now Toft was taken to London for further examinations , where she was quartered from November 29th in “Lacey's Bagnio”, a bathhouse or noble brothel in Leicester Fields , where she, always under the presence and strict control of St. Andrés, from countless others People were examined, scientists and curious laypeople, including the French physicist Claudius Amyand (1681–1740), the surgeons Thomas Braithwaite (1698–1731) and William Cheseldon (166–1752), the justice of the peace Sir Thomas Clarges, the theologian Philippus van Limborck , the physician and obstetrician John Maubray , the Dukes of Richmond and of Montagu , Lord Baltimore and others.

Maubray, author of the 1724 work The Female Physician, influenced by the early teachings of Hendrik van Deventer , had explained in this that women are able to give birth to mouse-like creatures, which Deventer Sooterkin and he called suyger . John Cleveland had written in 1654:

"There goes a report of the Holland Women, that together with their Children, they are delivered of a Sooterkin, not unlike to a Rat ..."

"The report goes that Dutch women give birth to their children as well as a sooterkin, not unlike a rat ..."

Up until the 17th century, the belief that women could bear animals was widespread. Jane Sharp , 17th century midwife who wrote The Midwives Book , the first book on obstetrics, also pursued this theory alongside Ralph Josselin , Caspar Peucer , Stephen Batman and Ralphe Nubery .

Maubray also showed himself to be an advocate of the "maternal impression" (influence of the mother's impressions on the fetus or the so-called "oversight" - an opinion that was also scientifically widespread up to the 19th century that conception and birth are through dreams or experiences of the Mother could be influenced.) And affirmed the possibility of these rabbit births.

James Douglas , personal physician to the Queen of England, on the other hand suspected - like Manningham, who had informed him of his investigations into the seized samples - fraud or a bad joke and, despite St. Andrés insistence, stayed at a distance. Douglas was one of the most respected anatomists in the country, was a member of the Royal Society and a well-known and widely respected obstetrician, while St. André was suspected of having become the royal personal physician only because he spoke the king's native German language. Douglas was convinced that a woman giving birth to rabbits was as likely as a rabbit giving birth to human babies, but eventually he gave in, visited Toft - and was completely convinced of the deception. Douglas and Manningham now wanted to bring their conviction to the public, but St. André and Howard persuaded them to wait a few more days, as Toft would certainly give birth to more rabbits soon and thus bring the ultimate proof of their sincerity.

Manninghams publication An exact Diary of what was observ'd during a close attendance upon Mary Toft, the pretended rabbet-breeder of Godalming, together with an Account of her Confession of the Fraud. was followed by Douglas' (“ I was very much surprised to find several affidavits… none indeed tending the truth… ”)

Details to clarify the case and the final confession

The final clarification of the case takes several people to claim.

Baron Thomas Onslow , a member of the Royal Family, had checked the events on his own and discovered that Toft's husband, Joshua, had been buying rabbits astonishingly many times recently, although to the amazement of the sellers he insisted that they were particularly small. In addition, Joshua was in strikingly close contact with the women who looked after Mary Toft in the bathhouse. Convinced that he had collected enough evidence, he announced in a letter to Hans Sloane on December 4th that he would publish his results on the case "which almost alarmed England" in the next few days.

That evening, the bathhouse porter Thomas Howard informed Sir Thomas Clarges, Justice of the Peace, that Toft had asked him to secretly procure a rabbit. Toft initially vehemently denied this, but later admitted that she had again had an enormous appetite for roast rabbit, so it was for consumption and not to cheat. Although she was now under house arrest and Douglas kept the visitors under strict control, Toft continued to plead her innocence and refused to admit that her story was a lie. But since then she has had no more deliveries. Douglas interrogated her again and again, but to no avail. Manningham finally pretended to have to perform a very painful procedure to prove that she was telling the truth. At the same time, Douglas interrogated her intensively and for hours. All this led Mary Toft to confess on December 7, 1726 in the presence of Manningham, Douglas, John Montagu and Frederick Calvert.

First she accused a mysterious stranger and later the wife of an organ grinder of having induced them to deceive. After she actually suffered a miscarriage in September, she later inserted dead rabbit parts into her vagina in order to then simulate an expulsion. In one of her later statements, she accused her mother-in-law and John Howard of complicity. She herself was innocently seduced, her mother-in-law planned everything out of greed. Her husband Josua Toft did not know anything, which, however, does not agree with the statements of the dealers who had sold Josua Toft the rabbits. After her miscarriage, her mother-in-law and the doctor pressed the body and paws of a small cat and the head of a rabbit into her uterus while her cervix was still open. They would also have made up the story that while working in the field she chased a rabbit and became so addicted to roast rabbit.

Toft's mother-in-law, on the other hand, remained steadfast despite numerous interrogations and denied any complicity. Mist's Weekly Journal of December 24, 1726 reported, “ the nurse has been examined as to the person's concerned with her, but either was kept in the dark as to the imposition, or is not willing to disclose what she knows; for nothing can be got from her; so that her resolution shocks others. ”

The British Gazetteer informed, also on December 24, 1726:

“A Prosecution is ordered to be carried on in the Court of King's Bench, next Hillary Term, against Mary Toft of Godalmin, for an infamous Cheat and Imposture, in pretending to have brought forth 17 præter-natural Rabbits. She is still detained a Prisoner in Bridewell, where none but the Keeper's Wife is permitted to go into the Room to deliver any thing to her; the infinite Crowds of People that resort to see her, not being suffered to approach her too near, and more especially her Husband, who is strictly search'd when he comes to the Prison. "

The British Journal reported that Mary Tofthad to appearbefore the Courts of Quarter Sessions in Westminster on January 7, 1727and was accused of " for being an abominable cheat and imposter in pretending to be delivered of several monstrous births " (German: " ein to be a despicable impostor for pretending to have had several monstrous births ”).

Aftermath

Although it was proven comparatively quickly that it was fraud, the scientific dispute continued long after Toft was charged with “ notorious and vile cheat ” (German: “obvious and hideous fraud”). The career of St. Andrés was ruined after the circumstances became known. Although he still tried to relativize his statements with a statement that appeared in various papers on December 9th and to blame other parties, but without success. Howard also went public with an advertisement dated December 15, 1726 and, like St. André, announced a detailed publication on his rehabilitation that would appear shortly, but neither of the two publications was ever published. Nevertheless, Howard seems to have continued to make a career in Guildford.

reception

In addition to the reports of the doctors and scientists directly concerned, which appeared in London in 1726, a second edition of a treatise by another doctor, Thomas Brathwaite, was published in London in 1727. In the same year the second edition of Nathanael St. André's reply was printed in the J. Clarke office in London. In the further course of the 18th century the story experienced many editions. In 1776 the eighth edition of the text by St. André appeared with an addition by Manningham. With the editions, details of the story also changed.

But not only doctors and printers of specialist material were interested in Mary Toft. When the rumor mill on London's streets spread their fate, newspaper makers eagerly reached for the story. Numerous gazettes brought the case to readers, including the Daily Post , the London Journal , The Craftsman , The Grub-Street Journal , The British Gazetteer , Mist's Weekly Journal and others. They were on display together with the then very popular leaflets and pamphlets in London coffee houses and harbor pubs, were read by seafarers and circulated among the population as stories and fables. The satirical engravings by the London engraver William Hogarth , which appeared under the titles Cunicularii, or the Wise Men of Godliman in Consultation (1726) and Gullibility, Superstition and Fanaticism (1762), could not change anything, although these works were also often reprinted and were widespread. Georg Christoph Lichtenberg commented on the engraving of gullibility, superstition and fanaticism with the words: "Quadrillings of rabbits ... see the light of day here in full gallop". He found the story amusing, but didn't believe it.

The incident was also the subject of the play The Surrey-Wonder, staged at London's Theater Royal . An anatomical farce . The graphic artist George Vertue made an etching of the same title, which shows a scene from the play.

Even Voltaire dedicated a separate chapter to history and St. Andrés views in his Singularités de la Nature from 1768 ("D'une femme qui accouche d'un lapin"); the poet John Byrom dealt extensively with the case, as did John Arbuthnot (under the pseudonym Lemuel Gulliver and Alexander Pope wrote a ballad . William Whiston sees in his memoirs of 1752 the fulfillment of the prophecy in Book 4 of Ezra , according to which the fall of Babylon is indicated, among other things, by the fact that monstrous women give birth to monsters.

Through her attempt at deception, Toft became so well known that the Dictionary of National Biography, first published in 1885 (more than 150 years after the events) dedicated an article to her. It also has a place in the follow-up book, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography .

Even 200 years later, the miraculous rabbit birth was again brought into the limelight. In 1912, Arthur Wallace published an account of the incident in the Liverpool Medico-Chirurgical Journal . In 1928 Charles Thompson took up the matter under the title Mysteries of History . In the 20th century, Mary Toft emerged as a prime example of deceitful servants in the UK encyclopedias. She has a firm place in the history of obstetrics, is mentioned in the Cambridge History of Science as one of the striking figures of the 18th century and serves in women's literature as an example of the hopelessness of poverty among women in the premodern era. In cyberspace , she leads her own life as a rabbit breeder .

interpretation

Aside from the gullible view of some newspaper articles, one might wonder how respectable academics could fall for this attempt at fraud. Were the eighteenth-century sages in England particularly stupid or ignorant? Didn't the people of that time know that humans can only give birth to humans? Indeed, the case did not seem as absurd at the time as it may seem today.

Mistake

The state of the art of science at the time said that the state of mind of a pregnant woman could be reflected in the shape of the newborn baby. This is how freak births were explained. This was also the current state of knowledge in Germany. In the Oeconomic Encyclopedia by JG Krünitz from 1858, under the heading oversight, the following entry can be found:

“The designation of an undeniable fact that occurs in pregnant women when the violently excited imagination makes certain vivid impressions on them, the consequences of which are visibly transferred to the womb, is also mistaken. The cases in which the mother's violently moving sight of deformities of various kinds has caused similar deformities in the child must be included here. The oversight has given rise to multiple disputes, in that some tried to deny the reality, indeed the possibility of such cases, and to demonstrate away, while others always recognized the most adventurous cases of the kind as true without criticism. "

Since Mary Toft reported about experiences with rabbits during pregnancy, which allegedly appeared to her in dreams, the incident became near to possible.

Monsters

The monsters, which have appeared as curiosities since antiquity, appear in particular in the 16th and 17th centuries. They were among the natural wonders why they attracted the attention of Paracelsus also went on like that of the natural magician Giambattista della Porta (1535-1615), but also the medical professionals interested These included a number of European doctors, among them the Zurich doctor Jakob Ruf , whose Publications on embryonic development are often cited in connection with monsters, Gerolamo Cardano , Ambroise Paré , or Fortunio Liceti , who published De Monstruorum Natura in 1616 , which is considered the beginning of the systematic study of embryonic malformations.

Originally treated morally and theologically or viewed as a sign of the end times, monsters increasingly became an object of entertainment and were often portrayed anecdotally in the course of the 16th century. The monster is increasingly turning into a curiosity, as an "appearance of the miraculous, as a manifestation of the mysteries of nature, as an example of the great diversity that God brings forth in his world" An important representative of this genre was Pierre Boaistuau with his Histoires prodigieuses , in which he dedicates half of the stories to monsters.

In the 17th and 18th centuries the scientific interest in all deviating natural phenomena, including monsters, was great. They were seen as a way to further uncover nature's secrets. Even Francis Bacon , the modern science is considered one of the founders, proposed to investigate "errors of nature", "until the cause has been found of such deviation." "It is therefore a compilation ... of all freak and wonderful natural products ... to be made."

In addition, it was only in the course of modern times that obstetrics was gradually integrated into medicine; Obstetrics as a medical discipline was not established until the late 18th century. In England, too, where male obstetrics was already more widespread than in other European countries, the doctors' knowledge and skills in the obstetric field were still poor. Physical examinations, especially vaginal examinations, were not a routine matter of course, but were also subject to a powerful taboo of shame. A negotiation process was required between the doctor, midwife and patient, and it depended on the patient's condition whether and to what extent the surgeon or medication was allowed to carry out physical examinations and how far he was allowed to go.

In this pre-Enlightenment "age of amazement" there was also a marked fascination for rarities and curiosities. The time was full of gullibility and superstition, absurdity, window dressing and charlatanry, with curiosity cabinets , show booths , traveling menageries and fairground attractions that displayed monstrosities of all kinds, showing giants and dwarfs, ape-men, Siamese twins and women without underbelly.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the public was entertained by Mary Toft's strange rabbit birth.

Contemporary bibliography

(Selection, sorted by time)

- John Howard: The wonder of wonders: or, A True and Perfect Narrative of a Woman near Guildford in Surrey, who was Delivered lately of Seventeen Rabbets, and Three Legs of a Tabby Cat, & c. 1726. Copy from 1851. The full text can be researched online. (PDF; 2.9 MB)

- Nathaniel St. André: A short narrative of an extraordinary delivery of rabbets performed by Mr. John Howard, surgeon at Guilford John Howard, Surgeon at Guildford. 1726. Full text searchable online (PDF; 4.1 MB)

- Cyriacus Ahlers: Some observations concerning the Woman of Godlyman in Surrey. 1726. Searchable in full text (PDF; 4.3 MB)

- Sir Richard Manningham: An exact Diary of what was observ'd during a close attendance upon Mary Toft, the pretended rabbet- breeder of Godalming, together with an Account of her Confession of the Fraud. 1726. Full text searchable online (PDF; 4.1 MB)

- Philalethes (pseudonym of James Douglas): The Sooterkin dissected. 1726.

- The several depositions of Edward Costen, Richard Stedman, John Sweetapple, Mary Peytoe, Elizabeth Mason, and Mary Costen; relating to the affair of Mary Toft, of Godalming in the county of Surrey, being deliver'd of several rabbits . 8vo. London: Pemberton, 1727. Full text searchable online. (PDF; 2.1 MB)

- James Douglas: An advertisement occasion'd by some passages in Sir R. Manningham's diary. 1727. Searchable online in full text. (PDF; 4.5 MB)

- Flamingo: A shorter and truer advertisement by way of supplement to what was published the 7th instant or, Dr. Douglas in an extasy at Lacey's Bagnio . December 4th, 1726, London, 1727.

- Lemuel Gulliver (pseudonym, attributed to John Arbuthnot): The anatomist dissected: or the man-midwife finely brought to bed .: Being an examination of the conduct of Mr. St. Andre. Touching the late pretended rabbit-bearer; as it appears from his own narrative. 1727. Searchable online in full text. (PDF; 3.7 MB)

- Alexander Pope: The discovery: or, The Squire turn'd Ferret. An excellent new ballad. To the tune of high boys! up go we; Chevy Chase; or what you please. Ballad. 1727. Full text searchable online (PDF; 2.9 MB)

- Thomas Brathwaite: Remarks on a short narrative of an extraordinary delivery of rabbets, performed by Mr. John Howard, surgeon at Guilford, as publish'd by Mr. St. Andre, anatomist to His Majesty. With a proper regard to his intended recantation. Searchable online in full text (PDF; 3.7 MB)

- Merry Tuft (pseudonym, attributed to Jonathan Swift): Much ado about nothing: or, a plain refutation of all that has been written or said concerning the rabbit-woman of Godalming .: being a full and impartial confession from her own mouth, and under her own hand, of the whole affair, from the beginning to the end. Now made public for general satisfaction. 1730. Searchable online in full text. (PDF; 2.7 MB)

- Andrew Clitor: A narrative of the most extraordinary delivery of Mary Toft. S. Barwell, 1774. Full text searchable online.

- Anonymous (attributed to Edward Hawkins): A philosophical inquiry into the wonderful coney-warren, lately discovered at Godalmin near Guilford in Surrey: being an account of the birth of seventeen rabbits born of a woman at several times, and who still continues in strong labor , at the Bagnio in Leicester-fields. (Manuscript). 1861 Searchable online in full text. (PDF; 2.8 MB)

- Flamingo (pseudonym, attributed to Edward Hawkins) A shorter and truer advertisement by way of supplement, to what was published the 7th instant: or, Dr. D - g - l - s in an extasy, at Lacey's Bagnio . December the 4th, 1726. (manuscript). 1861

literature

(Selection, sorted alphabetically)

- Alex Boese: The Museum of Hoaxes: A Collection of Pranks, Stunts, Deceptions, and Other Wonderful Stories Contrived for the Public from the Middle Ages to the New Millennium. Plume, 2003. ISBN 0-452-28465-1

- Jan Bondeson: A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities. WW Norton & Company , 1999. ISBN 0-393-31892-3 . Pp. 122-144

- Lisa Forman Cody: Birthing the nation: sex, science, and the conception of eighteenth-century Britons . Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-19-926864-9

- George M. Gould / Walter L. Pyle .: Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine. IndyPublish.com. Originally published in 1896. IndyPublish.com 2001. ISBN 1-58827-608-2

- Fiona Haslam: From Hogarth to Rowlandson: medicine in art in eighteenth-century. Liverpool University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-85323-630-5

- Tim Hitchcock: English sexualities, 1700-1800. Social history in perspective. Palgrave Macmillan, 1997. ISBN 0-312-16574-9

- Pam Lieske: The Mary Toft affair. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2007. ISBN 1-85196-842-3

- Jack Lynch, John T. Lynch: Deception and detection in eighteenth-century Britain. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2008. ISBN 0-7546-6528-3 .

- Lucy Moore: Con men and Cutpurses. Penguin, 2004. ISBN 0-14-043760-6 . Pp. 229-232

- Clifford Pickover: The Girl Who Gave Birth to Rabbits. Prometheus Books 2000. ISBN 1-57392-794-5

- Thomas Seccombe : Toft, Mary . In: Sidney Lee (Ed.): Dictionary of National Biography . Volume 56: Teach - Tollet. MacMillan & Co, Smith, Elder & Co., New York City / London 1898, pp 435 - 436 (English).

- Dennis Todd: Imagining monsters: Miscreations of the self in eighteenth-century England. University of Chicago Press, 1995. ISBN 0-226-80555-7

- Jennifer S. Uglow : Hogarth: A Life and a World. Faber & Faber 1997. ISBN 978-0-571-19376-9

- Philip K. Wilson: Surgery, skin and syphilis: Daniel Turner's London (1667-1741). Wellcome Institute series in the history of medicine. Rodopi, 1999. ISBN 90-420-0526-2

- Philip K. Wilson: Toft [née Denyer], Mary (bap. 1703, d. 1763), the rabbit-breeder. In: Henry Colin Gray Matthew, Brian Harrison (Eds.): Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , from the earliest times to the year 2000 (ODNB). Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-861411-X , ( oxforddnb.com ), as of 2004

Web links

- Worldcat

- SA Seligman: Mary Toft - The Rabbit Breeder .] In: Medical History , October 1961, 5 (4), pp. 349-360. PMC 1034653 (free full text)

- The curious case of Mary Toft. University of Glasgow, August 2009

- Josef Tutsch: In the shadow of the Enlightenment. The success story of the occult - from Gutenberg to the World Wide Web.

- Piper Crisp Davis: Falling into the rabbit hole: Monstrosity, Modesty, and Mary Toft. University of Texas, Dissertation, May 2009 (English)

- Wendy Moore: Of rabbit and humble pie . In: BMJ , May 7, 2009 (English)

- Collection of newspaper articles from 1726/27 on the fall of Mary Toft. (English)

- An Extraordinary Delivery of Rabbets: see the Mary Toft collection online. March 17, 2009. Wellcome Library (English)

- Mary Toft and the rabbit babies. Museum of Hoaxes

- Early 18th-Century Newspaper Reports, A Sourcebook. Rictor Norton

Individual evidence

- ↑ February 21, 1703 is given as the baptism date in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , the older Dictionary of National Biography has the year of birth 1701 marked with a question mark.

- ^ SA Seligman: Mary Toft - The Rabbit Breeder. In: Medical History October 1961, 5 (4), pp. 349-360. PMC 1034653 (free full text)

- ↑ Dmitri Gheorgheni: Mary Toft - The Woman Who Gave Birth to Rabbits. BBC, December 2005

- ^ Fiona Haslam: From Hogarth to Rowlandson: medicine in art in eighteenth-century . Pp. 30/31.

- ^ A b Lisa Forman Cody: Birthing the nation: sex, science, and the conception of eighteenth-century Britons. P. 124/125

- ^ A b c Philip K. Wilson: Toft [née Denyer], Mary (bap. 1703, d. 1763), the rabbit-breeder. In: Henry Colin Gray Matthew, Brian Harrison (Eds.): Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , from the earliest times to the year 2000 (ODNB). Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-861411-X , ( oxforddnb.com ), as of 2004

- ^ Nathaniel St. André: A short narrative of an extraordinary delivery of rabbets performed by Mr. John Howard, surgeon at Guilford John Howard, Surgeon at Guildford. P. 9.

- ^ White Knights library. Oxford University. 1819. p. 195

- ^ A b Philip K. Wilson: Surgery, skin and syphilis. P. 6.

- ↑ a b c Political state of Great Britain. Vol. XXXII for December 1726. Oxford University. P. 599f.

- ↑ a b c James Caulfield: Portraits, Memoirs, and Characters of Remarkable Persons form the Revolution in 1688 to the End of the Reign of George II. 1819. p. 203

- ↑ a b c Economic Encyclopedia by JG Krünitz from 1858, keyword Versehen

- ↑ Jack Lynch, John T. Lynch: Deception and detection in eighteenth-century Britain. Ashgate Publishing, 2008, ISBN 0-7546-6528-3 , p. 144.

- ^ Cyriacus Ahlers: Some observations concerning the woman of Godlyman in Surrey

- ^ Jan Bondeson: A cabinet of medical curiosities. Pp. 128/129

-

↑ A short narrative of an extraordinary delivery of rabbets ,: perform'd by Mr John Howard, Surgeon at Guilford, (1727) - Internet Archive or

St. André: A short narrative of an extraordinary delivery of rabbets, perform'd by Mr John Howard, Surgeon at Guilford - Internet Archive - ↑ St. André, p. 21

- ↑ p. 32

- ^ Philip K. Wilson: Daniel Turner's London (1667-1741). Mary Toft's Imagination. Rodopi, 1999, ISBN 90-420-0526-2 , p. 113.

- ↑ a b Sir Richard Manningham: An exact Diary of what was observ'd during a close attendance upon Mary Toft, the pretended rabbet- breeder of Godalming, together with an Account of her Confession of the Fraud. 1726. Full text searchable online (PDF; 4.1 MB)

- ↑ Manningham, p. 14

- ↑ Manningham, p. 19

- ↑ St. André

- ↑ Back then, the term “Bagnio” was often used for a brothel with a Turkish bath.

- ↑ Lisa Forman Cody: Birthing the nation: sex, science, and the conception of eighteenth-century Britons. P. 126

- ↑ John Cleveland: A Character of a Diurnal Maker. London, 1654.

- ↑ AWBates: The sooterkin dissected: the theoretical basis of animal births to human mothers in early modern Europe. 2003 (PDF; 314 kB)

- ↑ Bondeson, p. 132

- ↑ James Douglas: An Advertisement ocasion'd by some passages in Sir Manninham's Diary lately publish'd. (PDF; 4.5 MB)

- ↑ Dennis Todd: Imagining monsters: Miscreations of the self in eighteenth-century England. P. 31

- ↑ Manningham, p. 32

- ↑ Seligman, p. 356

- ↑ Todd: Imagining monsters . P. 5/6

- ↑ Haslam, p. 34

- ↑ Todd: Imagining monsters . P. 7

- ↑ Ronald Paulson: Hogarth's Graphic Works , 3rd ed., London 1989, pp. 69-70, 177-178. Bernd W. Krysmanski: Hogarth's Enthusiasm Delineated. Imitation as a critique of connoisseurship , Hildesheim, Zurich, New York 1996, Volume 1, pp. 206-210.

- ↑ Wolfgang Promies: Lichtenbergs Hogarth , Munich and Vienna 1999, pp. 95-100.

- ↑ chap. XXI., P. 69

- ^ Richard Parkinson: The Private Journals and Literary Remains of John Byrum. The Chetham Society Publications, Manchester. 1854-57. vol. 1, pt. 2, page 386)

- ^ Gulliver, Lemuel (pseudonym): The anatomist dissected or the man-midwife finely brought to bed.

- ↑ Jonathan Swift, Christopher Fox: Gulliver's travels: complete, authoritative text with biographical and historical contexts, critical history, and essays from five contemporary critical perspectives , Palgrave Macmillan, 1995, online at books.google.de

- ↑ [POPE A.)]: The discovery: or, the squire turn'd ferret. 1727.

- ↑ James E. Force: William Whiston, honest Newtonian. Cambridge University Press, 1985. ISBN 0-521-26590-8 . Footnote 55, p. 163

- ↑ 1749 manuscript , beginning with "'Tis here foretold that there should be signs in the Women, or more particularly that menstruous Women should bring forth monsters."

- ↑ Thomas Seccombe: Toft, Mary . In: Sidney Lee (Ed.): Dictionary of National Biography . Volume 56: Teach - Tollet. , MacMillan & Co, Smith, Elder & Co., New York City / London 1898, pp. 435 - 436 (English).

- ↑ Sabine Doering-Manteuffel : The occult. A success story in the shadow of the Enlightenment - From Gutenberg to the World Wide Web. Siedler Verlag 2008. ISBN 978-3-88680-888-5

- ↑ Rosemarie Zeller: Monsters in the early modern times . (PDF; 1.0 MB)

- ↑ Rosemarie Zeller: Monsters in the early modern times . (PDF; 1.0 MB) p. 13

- ↑ Histoires prodigieuses. Pierre Boaistuau, France, 1560 . ( Memento of the original from November 11, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Wellcome Collection

- ^ Francis Badon: New Organon. No. 29. pp. 267/268

- ↑ Marita Metz-Becker: The administered body: the medicalization of pregnant women in the birthing houses of the early 19th century. Campus Verlag, 1997. ISBN 3-593-35747-X . P. 32

- ↑ Todd: Imagining monsters . P. 5

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Toft, Mary |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Tofts, Mary; Denyer, Mary (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English housemaid who became a media event as the "rabbit woman" |

| DATE OF BIRTH | baptized February 21, 1703 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Godalming |

| DATE OF DEATH | buried January 13, 1763 |

| Place of death | Godalming |