Wandermenagerie

Wandering menageries were collections of living exotic animals on tour. They became an integral part of everyday entertainment culture across Europe and the United States from the second half of the 18th century. The menageries were operated by showmen who moved with the animals from place to place in order to present them to an audience in animal booths for a fee. In contrast to the circus , the sensation of these animal shows was not primarily in the dressage of tamed animals, but in the display of their strange peculiarities.

In contrast to the zoos that established themselves in the 19th century , which are dedicated to researching creatures and educating the public, the animal displays of the wandering menagerists primarily focused on the curiosity that was served by the traveling trade everywhere. In Europe, the era of mobile animal shows ended in the 1930s; in the USA, traveling menageries remained in place until the 1960s.

Look and collect

The tradition of exhibiting living exotic animals has been documented in Europe since ancient times . Since the Middle Ages , jugglers have roamed the country with live animals in Europe; Dancing bears were part of the picture of medieval and early modern regional and urban market events.

The collecting of strange creatures was a more recent phenomenon, which had belonged to the court of European rulers since the early modern period and which increasingly turned rare animals into objects of exchange and diplomatic gifts, such as the so-called Medici giraffe , which was on frescoes in the 15th century and paintings was immortalized. In menageries specially set up for big cats and elephants , the animals, like the princely chambers of curiosities and natural objects , expressed an exclusive claim to entertainment and the satisfaction of curiosity. The animals often did not stay in the same place, but were shown around as a sign of the power of their owners, in particular the tamable Asian elephant , which has been seen again and again in Europe since the Middle Ages. For example, Louis IX. In the 13th century an elephant went to England , Pope Leo X. received a young elephant named Hanno from Portugal from the possession of Manuel I and an elephant that went down in history under the name Soliman moved on its way to Vienna via Lisbon and Madrid its princely owners.

At the end of the 18th century, the ruling menageries were increasingly disbanded. Unless the animals ended up skeletonized in the natural history cabinet, they were either distributed via the trade in exotic animals to zoological gardens, which were set up for the public at the beginning of the 19th century, or they supplemented the circus as trained attractions and became part of the showmen's mobile animal collections .

Jugglers and traders

Animal performances with tame wild animals and small dressage numbers were part of the modern public entertainment program for traveling showmen and comedians . Since the end of the 15th century, bears and monkeys have often been shown together with moors and human malformations . Indian elephants, who were able to perform tricks as docile animals, such as the Hansken elephant and Bernini's elephant , became crowd- pullers in the 17th century. In the 18th century, a living Indian rhinoceros named Clara was presented on a European tour. The occurrence of such strange, sensational wonders of nature was consistently recorded in local annals and immortalized in works of art by artists such as Jean-Baptiste Oudry .

The regular ship connections created a market for rare animals in Europe, initially especially in the overseas ports. Around 1700, with the exotic animals landing in Amsterdam , which were not immediately brought into the menageries of rulers by the princely agents, so-called trade and foam nageries were created; Animal handlers moved with the stocks to the residential cities in the hope of princely customers. Just like the traveling stages , the traveling animal keepers occasionally made guest appearances at the court theaters .

In the second half of the 18th century, the spectrum of animals on display was expanded to include the so-called "royal animals", the elephants and lions , which were presented to an affluent audience by companies that were now developing independently. The public organization of animal fights , in which dogs often had to fight bears, wolves or tigers , has been gradually banned by cities across Europe since the beginning of the 19th century. The bans in Germany (from 1830), Great Britain (from 1835) and Paris (1833) followed the ideas of the presentation of wild animals drafted in Paris during the French Revolution in 1793, which had propagated a public menagerie committed to the Enlightenment and with it corresponding campaigns against the Start animal fights in Europe.

From the prince to the zoo and the showroom

After the death of Emperor Franz Stephan in 1765, his exquisite animal collection was opened to the public in Schönbrunn near Vienna ; the Schönbrunn zoo therefore regards itself as the oldest zoo in the world. On August 10, 1792, the Jacobins destroyed the famous, but neglected menagerie in Versailles and immediately gave numerous wild animals to stuff . The killing of the remaining animals and their transfer to the natural history cabinet was prevented by the successfully implemented plan by Bernardin de Saint-Pierres , writer and head of the cabinet, to bring the animals to the Jardin national des Plantes . The public menagerie established for them there in 1793 , which still exists today, was determined by its scientific ambition, by the idealization of nature in the form of a park design and by the interest in national prestige and thus showed the hallmarks of the modern zoo in the 19th century. Century on.

The expensive private animal collections came on the market and in this way made it possible for the fairground trade to add an attractive addition to their holdings. One of the last to be sold was the important menagerie of King Friedrich of Württemberg , due to persistent crop failures and famine in the country. After Friedrich's death in 1816, his successor Wilhelm had one of the elephants killed and transferred to the royal natural history cabinet. He immediately put the big cats and another elephant on the market, and he also put the menagerie building up for sale. The equestrian , circus principal and showman Jacques Tourniaire (1772–1829) acquired several parrots , an ostrich , some great apes and the elephant ; For the elephant alone he paid 1,100 florins .

The animal traders, who mainly secured the elephants and the predators, led them throughout Europe as wandering showpieces at times. In addition to monkeys and parrots, the Berlin animal dealer Garnier bought a leopard , an elephant and a bear from the royal Württemberg collection . Garnier's elephants in particular became the attraction of his traveling showroom; two of the elephants perished spectacularly on their tours in 1819 and 1820.

Animal show

The traveling menageries of the 19th century took over the dramaturgy of the combination of different animal species of strange faunas from the ambulant animal demonstrators of the 18th century , initially with the intention of showing them to the amazed audience in a peaceful side by side. Big cats , which had been bred by showmen since the beginning of the 19th century and were therefore usually tame, as well as giant snakes and hyenas , however, provided a welcome opportunity to convey the dangers of wild nature. The showmen increasingly showed themselves in their animal booths as tamers , as tamer of bloodthirsty beasts; Demonstrations of cute, trained puppies were part of the program.

Animal shack

The showmen with animal menageries belonged to the traveling people . They transported their animal collections on horse-drawn carts in cages in which the animals were also kept. On the journey, the cages were locked except for light and air windows to protect the cargo from wind and weather as well as from being viewed free of charge. At the location of the performance, the animal boxes were set up in a row. Simple wooden walls or tarpaulins around the open lattice sides of the cages protected the showpieces from the curious glances of the non-paying visitors and, with an entrance at one end, resulted in a space that was closed on all sides and accessible to the audience. A tarpaulin attached above protected the animals and the performances from sun, wind and rain. The winter quarters consisted of permanent stalls that were specially built and sealed against the cold with straw and sawdust.

In the animal shack the audience was separated from the cages with the wild animals by barriers. The cheaper places were set up some distance from the animals; The showman explained his collection up close to visitors who were willing to pay a higher entrance fee. Colorful birds - mostly parrots - could swing chained on hangers under the tent roof. An elephant, which was still the greatest attraction for the visitors, was always exposed.

In the event of financial success, the showmen invested the profit in increasing their animal populations. The cages transported on wagons became lattice wagons, which from 1850 onwards were consistently transported by rail from the larger menageries and the number of them required a double-sided display at the fairs . The wagons were covered with a closed tent and the larger interiors were equipped with stages for special performances by the showmen with individual animals. The audience was divided into "tiers", the most expensive places were still those in the immediate vicinity of the animals. The entrance was decorated throughout with large announcement boards, colored paintings on wood or jute depicting dramatic animal scenes. The colorful gable trim also clad the mobile and correspondingly temporarily acting tent and boards Arrangement and offered visitors a to the fixed sideshows reminiscent optics. The entrance had space for performances that offered a foretaste of the spectacle to be expected inside the booth .

Dramaturgies

The animal shows already began in front of the entrance, where the showmen loudly aroused the curiosity of the visitors by presenting their monkeys and parrots or even a camel on a ramp for free, in order to provide the visitors with a view of the actual attractions, such as to lure the big cats and elephants into their booth. An explicator inside the booth provided information about the animals, mostly in a mixture of information and myths; The showmen usually drew their knowledge of animals from Buffon's Histoire naturelle from the 18th century. The large wild animals were all hand-tame as they had often been bought as young and raised by their owners. Nevertheless, their display in the cages gave the paying audience the thrill promised at the beginning and at the same time the experience of superiority over the smell and screams of wild nature.

From around 1820 the menageries increasingly included dressage in their program with the aim of showing the domesticated predators in motion, whereby the voluntary submission of wild animals to the will of humans was expressed. Snake tamers presented their animals without protective bars in the middle of the audience, sometimes surrounded by a free-roaming pelican or a peacefully eating dromedary . In the course of the 19th century and with increasing earnings, competition dictated that animal stall visitors be shown the confrontation between beasts and humans as an attraction. Animal tamers appeared in the cage together with various types of big cats, whereby they did not perform any dressage acts, but made the still tame animals hiss and urged them to act dangerous with whip and stick. Elephant and alligator came on stage.

When a visit to the animal shack had long since become a Sunday leisure activity for the family at the end of the 19th century, the showmen erected small side tents in which they had dressage acts performed with small animals.

Organization and profitability

The Dutch port cities and, in the post-Napoleonic period, the port of London were among the most profitable places in the animal trade . The exotic animals made their way from London to Hamburg or Bremen , where important transshipment points for the animal trade developed on the continent in the 1820s and 1830s. In addition to elephants, lions and tigers, zebras and tapirs , which were valued as attractions by menagerists, were among the most sought-after and most expensive animals traded ; Rhinos , giraffes or even a hippopotamus remained rarities and came to the zoos.

Animal shows required a fee-based permit to perform in the cities and municipalities; Sometimes taxes had to be paid to local social institutions, such as the poor relief funds. The traveling menageries also had to consider the visitor potential when choosing their venues; Trade fair cities or cities with large annual fairs were among the so-called "large stations". In addition to the wagon castles and tents that were brought with them or the temporarily timbered stalls on the marketplaces, rented permanent showrooms, inns and hotels were occasionally venues for animal shows.

The comparatively high income from the sale of animals and entrance fees contrasted with considerable investments in purchasing, keeping and transport. Advertisements in the form of printed notices, posters and brochures had to be written, printed and distributed in advance for the locations of the displays. The loss of capital due to the loss of animals could often only be partially compensated for by selling the carcasses to the natural history museums . Fluctuating prices and the not always foreseeable demand in addition to the entrance fees dictated by the municipalities also made the hiking menagerie a business with a risk that was difficult to calculate. For example, the successful menagerist Jacques Tourniaire had sufficient capital around 1828 to be able to invest in the construction of a circus building in St. Petersburg as one of the financiers , which, however, was never realized. Madame Victoire Leclerf, on the other hand, was not allowed to leave the city of Frankfurt am Main with her elephant Baba in 1826 , because “the effects of the same were confiscated because of a claim made on Mrs. Leclerf ”.

Migrating animal collections

The number of traveling menageries increased steadily from the beginning of the 19th century. Often there were small groups of showmen with one to a maximum of two dozen animals; some traveling animal shows, however, gained a considerable amount of up to several hundred living exhibits in a few years. The owners of the large menageries raised young animals and, since the middle of the century, have often worked with the zoos to set them up or set up their animal collections themselves in a town. Some traveling menageries introduced the ring and founded a circus.

Italy and France

Some of the important animal guides in Italy and France in the second half of the 18th century came from families of comedians and often showed their wild animals together with other curiosities, such as strange artefacts and natural objects, panoramas and exotic people. The comedian Jean-Baptiste Nicolet, who wandered through Italy and France with eleven animals in the 1770s, called his animal show a menagerie in 1776 , thus introducing the term for outpatient animal collections. On Nicolet's notice from 1777 - with royal privilege - an "orangoutan" is noted. Antonio Alpi (also Albi or Alpy ) moved with several reindeer from Lapland to France in 1784 . In 1798 his possession is documented in an animal show which he had put together in London and which included two Asian elephants; Alpi sold this collection to the imperial menagerie in Vienna in 1799. Around 1800 he was traveling with a new collection in Northern Italy, Switzerland and in German-speaking countries; In 1814 he was named as the owner of an Indian rhinoceros.

In France, the ring prevailed with the public and, since the late 18th century, based on Philip Astley , who is regarded as the founder of the modern circus, in particular the sophisticated horse dressage; the high school was part of the circus program and was successfully taken to Russia, for example by Jacques Tourniaire. Astley had invented the combination of acrobatics and horse training in London in the 1770s ; it was picked up by Antoine Franconi in his Cirque Olympique in Paris in the 1820s. The horse theaters with their spectacle pieces and re-enacted battle paintings were popular . In his theater decree of 1807, Napoléon prohibited these boulevard performances, which were particularly popular with Paris audiences, from being run as a "theater".

Animal shows such as those shown by the traveling menageries in Great Britain and Germany have been cultivated in France since the beginning of the 19th century in the traveling companies with livestock as a trained staging. The dressage performances were complemented by mimes , Feerien and clowning and were more like animals occupied theater performances. Large carnivores were shown comparatively late in France. In 1831 at the Cirque Olympique in Paris, the French Henri Martin (1793–1882) performed a pantomime entitled "Les lions de Mysore" ( The Lions of Mysore ) with his lions Charlotte and Coburg . Martin became famous for his predatory training, with which he traveled through Europe between 1823 and 1829. Honoré de Balzac's story Une passion dans le désert , published in 1830 (German: A passion in the desert , 1908), was inspired by Martin. After he retired from the life of a showman in 1837, he advised the Amsterdam Zoo, which was founded in 1838, and was appointed to the board of directors of the Rotterdam Zoo in 1857 .

Great Britain

In the first half of the 19th century, Wombwell's Traveling Menagerie became the UK's most successful traveling animal show . George Wombwell (1777–1850), a shoemaker based in London since 1804 , had roamed the bars with two boas he had bought in the docks and had made some money with them. In the port of London he continued to buy exotic animals brought by ships from all over the world. In 1810 he founded a traveling menagerie. Ten years later, Wombwell was driving his collection of animals across the country in 14 wagons pulled by 60 horses. Wombwell showed Asian elephants , kangaroos , leopards , lions and tigers as well as a rhinoceros. The greatest peculiarity, a young female gorilla ("Jenny") who survived in the circus for seven months in 1855/56, was misjudged as a chimpanzee - Jenny was the first gorilla to reach Europe alive. Wombwell also bred and raised wild animals himself, including the first captive-born lion in Britain named William . Wombwell expanded his business over the years to a total of three menageries and was invited five times to the royal court, where he showed off his animals to Queen Victoria and cured Prince Albert's dogs. Wombwell's grave monument in Highgate Cemetery received the sculpture from Nero , his favorite lion.

Between 1856 and 1870 the English circus Sanger owned the largest collection of exotic animals of any traveling menagerie in Great Britain. During this time the company made the combination of animal shows and acrobatics popular, following the example of Astley and the Cirque Olympique .

Netherlands and German-speaking countries

The most famous traveling animal shows in the 19th century not only in the Netherlands, but also in Germany and Austria belonged to the van Aken family (also: van Acken or van Aaken ). The show companies emerged from a trading menagerie in Rotterdam , founded in 1791 by Anthony van Aken. Van Aken's four sons and daughter got into the animal business and showed their exotic creatures with some competing companies from 1815 in German-speaking countries and later throughout Europe, whereby the siblings knew how to divide the continent profitably when choosing their travel routes.

In the years 1837 and 1849 the animal tamer Gottlieb Christian Kreutzberg acquired the animal stocks of the two older brothers Anton and Wilhelm van Aken and thus founded his own, successful traveling animal show. According to traditional newspaper advertisements and announcements, the Kreutzberg menagerie has appeared at fairs and festivals in many places for a good three decades since the mid-1830s. From the end of the 1850s, two of Gottlieb Kreutzberg's sons also roamed the country with their own animal shows. A brochure by Menagerie G. Kreutzberg , first published probably in 1835 and later again in the 1850s, names a population of over 50 animal species, including a Berber lion , a subspecies of lions that is now extinct in the wild. The brochure notes trained lions and hyenas and, as a special attraction, the Indian elephant Miss Baba .

Gottfried Claes Carl Hagenbeck (1810–1887), fishmonger in Hamburg , had shown six seals at the fish market in St. Pauli in 1848 , which the fishermen who supplied him had caught. The seal show brought him not only money, but also an immediate appearance of the animals, which had hardly been seen on land until then, in Berlin , where he sold them and built up an animal trade with the proceeds from the events. In 1866 his son Carl (1844–1913) took over the business and expanded it all over Germany and later overseas to the USA. Carl Hagenbeck jun. had his own animal suppliers all over the world and expanded the animal shows to so-called people shows , at which he also let people appear who he had brought from the homeland of his animals. After the death of his father in 1887, he founded a circus. In 1907, with Hagenbeck's Tierpark in Hamburg , Hagenbeck realized the first zoo in the world without bars, in which the animals were allowed to roam freely in an artificially created landscape. A special feature was the artificial mountain range, which was supposed to create the illusion of a natural fauna. The Hagenbeck zoo is still one of the world's most famous zoos.

Karl Krone , born on September 19, 1833 in Questenberg in the Harz Mountains, developed an interest in the animal shows through the Alexander Philadelphia's menagerie, which was a guest in the Harz city . He married one of Philadelphia's daughters, Frederike; the couple had a daughter and two sons. In 1870, in which his son Carl was born, Krone and his wife founded the Menagerie Continental , which he was able to lead to increasing attention from the public in the following years, in particular through show numbers based on the docility of the wild animals. After his son Fritz, whom Krone had planned as his successor and who trained the bears, was killed in an accident with one of his animals, Carl joined his father's company. Carl Krone jun. placed particular emphasis on animal training, for which a separate tent extension was built, attached to the animal shack of the Continental Menagerie . In 1893, as the tamer , he showed Charles the sensational ride of a lion on a horse for the first time in the history of animal training. When his father Karl Krone died in 1900 during a guest performance in Frankfurt (Oder) , Carl became head of the traveling troupe, which had meanwhile been known as the Menagerie Circus of the trainer Charles . In 1905 he founded the Circus Krone , a well-known circus company that still exists today, since 1919 with a permanent seat in Munich .

United States

Animal shows in the USA differed from the European ones in their far larger proportions of the animal populations. Following the British model, they combined the animal presentations with circus attractions and supplemented them with the curiosity show .

The American Isaac van Amburgh (1811-1865), a traveling animal dealer from Fishkill, New York State , made his debut as a lion tamer in New York City in 1833 and performed in front of Queen Victoria on a tour of England in 1839. Edwin Henry Landseer (1802–1873), preferred animal and court painter to the Queen and her Prince Consort, staged him in a painting in the midst of his big cats with a lamb in front of his chest. Twenty-year-old Victoria attended Van Amburgh's performance at the Drury Lane Theater several times and bought Landseer's picture. Isaac van Amburgh died of a heart attack in Philadelphia in 1865 and left legends for reading books.

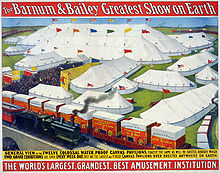

The largest company in the second half of the 19th century was the PT Barnum (1810–1891) traveling show . Barnum maintained a museum of curiosities and from the 1870s onwards offered spectacular animals and curious people for viewing for a high fee in PT Barnum's Great Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan, and Hippodrome . For example, he showed the giant elephant Jumbo and had albinos and Siamese twins perform in their own shows. In 1885 Barnum merged with the James Anthony Bailey Circus to form Barnum and Bailey: The Greatest Show on Earth , the largest traveling company of its time, which issued shares and expanded the operation of the animal and curiosity show into a traveling amusement park. When the company, later trading as Barnum & Bailey Circus , went on a European tour between 1897 and 1902, it had more than 500 horses, over 20 elephants along with rhinos, hippos, giraffes and gorillas in the company's own railway wagons and was thus able to show animal species, some of which who didn't own zoos.

The end of the 20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century the wandering animal shows were with their extraordinary part dimensions with respect to the accelerating strengths technical and sporting entertainment machineries as Kintopp or six-day race , consistently forced to integrate in circuses or zoos. The animal shows, which continued to roam the country independently, returned to the more modest dimensions of their early days at the beginning of the 19th century. In contrast to the menagerists of the 19th century, some of whom achieved prosperity and prestige, the operators of wandering menageries were now, like their centuries-old juggler ancestors, as traveling businesses in the role of social outsiders. Before the First World War until the 1920s, they stocked the hype with costumed monkeys and thinking horses; the flea circus enjoyed some popularity. There were dog and monkey theaters in which the animals were moved around in small scenes; the rat and mouse theaters were somewhat rarer.

The German Animal Welfare Act of 1933 prohibited roaming around with wild animals in the German Reich . In the United States, smaller companies continued to be an attraction in amusement parks and so-called sideshow shows in the period after the Second World War until the 1960s . In the Federal Republic of Germany , operators of animal and dressage demonstrations who occasionally appeared at shooting festivals were increasingly banished by the administrations to the outskirts of towns and communities. The animal demonstrators, who appeared in the shopping streets with llamas or donkeys in the shopping streets until the end of the 1950s and who advertised their mostly distant events, disappeared from the image of modern inner cities in the 1960s. The Swiss Circus Knie is going on tour today with an animal show from the holdings of Knie's Children's Zoo . Other hiking zoos that appear differently are either a nostalgic mix between the hiking menagerie and the zoo, such as B. various insect and reptile shows, or turn out to be ephemeral events with animals to touch.

Traveling menagerie in art and poetry

The animal painting took in the 19th century an upswing, not least due to the mass book printing in 1840 and the opportunities lithographic integrate color plates, and reinforced by the onset of production of children's books . The public zoos encouraged the painters to be fascinated by wild animals. The traveling menageries, frequented for everyday entertainment, created a growing public for this subject in visual art, who could also find the forms of animal shows in joke sheets. Animals have always been a preferred motif in poetry since the Middle Ages , and the wandering animal stalls found their way into literary works in Romanticism . A comprehensive bibliography on animal show in fine literature is not yet available.

art

Heinrich Leutemann (1824–1905), an animal draftsman and illustrator of children's books, who also worked for journals and magazines, was one of the artists who devoted himself to the traveling menagerie . Through his acquaintance with Carl Hagenbeck, Leutemann got the opportunity to record his animal shows as well as the exotic stock of Hagenbeck's animal collection in numerous drawings and watercolors . The arrival of the rare animals in Hamburg was just as much a subject as the representations of genre scenes , such as the preparation of animals for a show. The originals of the drawings produced by Leutemann for print became coveted objects for art collectors.

Paul Friedrich Meyerheim (1842–1915), whose catalog of works includes 63 paintings depicting exotic animals in the zoo and animal shack, was one of Berlin's preferred animal painters. In his menagerie paintings, Meyerheim not only attached great importance to the details in the animal shack, but also designed an artistic picture of the events that tried to draw the viewer into the atmosphere of the stall. Unlike in the representations of Pietro Longhi or Johann Geyer, which concentrated on the essentials of the animal shows, Meyerheim gives the curiosity an artistic expression in a special way. The composition, crammed with details up to the edges of the picture, invites the viewer to step into the picture and to feel like a fascinated participant. Meyerheim's menagerie depictions were in great demand; some of them were made to order. His menagerie paintings were widely distributed through reproductions in print.

Wandering menageries were also a popular subject for satire in the 19th century . In England in particular, the typical ambience of animal stalls and animal shows was repeatedly used as an opportunity to ridicule personalities from the court and from politics. Napoleon is occasionally carted through the gawking crowd in a cage or the exotic animals take on the faces of familiar contemporaries of public life. The menagerists themselves were occasionally targeted by satirists, with their screaming announcements and their presentation being made a mockery. A joke sheet from 1839 targets the Anton van Akens traveling menagerie. With the typical picture accessories of the animal show, a “Herr von Aalen” is presented as a “Schreimann” in “cannons and lederhosen with long spurs on feet”.

poetry

In the short story Novelle , published in 1828, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe clarified the hustle and bustle of an animal shack as a place that promises more on the poster outside than it shows inside. A fire breaks out at the fair and causes the tiger to break out and to meet the princess on horseback, who feels threatened by the big cat. The tiger is shot by her companion, and the showman family laments the death of their tame and harmless animal. The child of the showman is able to lure the also runaway lion out of his hiding place with singing and playing the flute and in the end pulls a thorn out of his paw. In a conversation with his secretary Eckermann on the title of the story, Goethe found on January 29, 1827 that a novella was an "unheard of incident" and thus provided a definition of the novella as a literary genre that is still valid today .

In a poem entitled The Lion's Bride , written in 1827, Adelbert von Chamisso used the romantic motif of the beautiful woman with the beast ( la belle et la bête ) as a tragic variant of the death of an animal keeper's daughter. A young bride, raised from an early age with a lion of the same age, says goodbye to the animal in its cage before their wedding. When the groom shows up, the lion blocks the exit and kills the girl as she tries to escape the cage; the groom shoots the lion. Robert Schumann set Chamisso's Löwenbraut (op. 31) to music in 1840 as one of a total of 138 songs and thus helped her to maintain its popularity.

In the memoirs of Eugène François Vidocq (1775–1857), a criminal and forensic scientist, published in 1828, the first-person narrator describes how, as a failed son, he found employment in an animal shack after a failed attempt to emigrate to America may not really like it in the long run. The “director”, according to the first-person narrator, was “Cotte-Comus, who was so famous at the time,” who “did business with the naturalist Garnier, a famous animal trainer”. The alleged memoirs written by an anonymous author and several times as a vagrant life also translated into German.

The 1890/91 first in a magazine in sequels released adventure novel Treasure of Silver by Karl May (1842-1912) begins aboard a paddle steamer on the Arkansas , to which an animal showmen a black panther transported. During the feeding demonstration arranged for the passengers traveling with them, the menagerist is killed by the animal, which then frees itself from its cage and threatens a lady and her daughter. An Indian saves the girl by jumping into the water with her. The return of the noble savage on board with the child is "greeted with roaring cheers". The panther, also jumped overboard, perished in the river.

reception

The exotic animal as a symbol of princely sovereignty became unpopular at the end of the baroque era . It changed its function and from then on served more for the public definition of something strange or abnormal, but which could not be really dangerous. For this to happen, the belief in the devil and ghosts had to have settled in the lowest social classes and had spread confidence in a rational world order, as was increasingly the case since the 17th century. Even in the 18th century, animal tamers were occasionally suspected of witchcraft, for example on the occasion of a depiction of Faust with trained animals in 1721.

The philosopher Michel Foucault characterized the menagerie with the thesis "the bestiality was not in the animal, but in its domestication". It is an exclusion principle for the abnormal since absolutism , which applied to humans as well as animals. He compared madhouses and clinics such as the Hôpital Salpêtrière with animal menageries: "You let the guards display the mad, as the trainer shows the monkeys at the fair in Saint-Germain ."

Enlightened perception

Since the end of the 17th century, scholars have regarded exotic animals as natural objects; Traditional conceptions of miracle animals and fantasy creatures , the existence of which had been written about since the Middle Ages, had to be countered with one's own perception. The spread of this approach shaped the perception of animal shows in the late 18th century; the wandering menageries of the late Enlightenment certainly earned merit in popularizing tangible knowledge about nature. The animal shows were cause for astonishment for the lay public, and for the artists they were the inspiration for processing the exotic subjects from the stalls. The naturalists, increasingly interested in the systematic recording of the animal world, had mainly used the natural history cabinets. Buffon and Linnaeus included animals in their natural history that they had seen at animal shows.

In the first third of the 19th century, zoologists expressed their criticism of the presentations of the migrating animal collections. The often freely invented names for the animals were criticized as well as the false and gimmicky explanations by the showmen. Furthermore, the exaggerations noted on the notice sheets were condemned, such as the menagerist Hermann van Aken had spread in 1828 in the claim that snakes could entwine a buffalo . Sir Stamford Raffles decided in 1825 that wild animals should no longer be the subject of vulgar display; he promoted the establishment of the London Zoo . The commercially successful menageries of the second half of the 19th century played no role in zoology; the zoological gardens were considered places of serious observation of animals. The forms of animal husbandry in the traveling collections also met with early criticism; In 1830 the misery of keeping cages and the ignorance of the guards were noted in the face of British traveling menageries.

Modern science

The animal shows attracted attention in science at the end of the 20th century, especially in connection with studies of the zoo and circus history, as the connections and transitions took place simultaneously and fluently. In individual examinations, such as animal painting in the 19th century, depictions of the outpatient menageries can also be found occasionally. An examination of Paul Meyerheim's menagerie paintings, published in 1995, suggests the agony of the large wild animals kept behind bars in the animal huts; the expression of the wildness of a polar bear biting into the bars, intended by the painter in an authentically created picture from 1895 , is recognized as the "madness" of the creature with abnormal behavior.

Since 1999, is the work of Annelore Rieke Müller and Lothar Dittrich , the way with wild animals. Wandering menageries between instruction and commerce 1750–1850 , the first extensive study of animal collections that migrated through Europe until the middle of the 19th century. The study is based on the holdings in museums, archives and private collections. Personal records of menagerists, such as memoirs or diaries that could provide information about the everyday life of the wandering menageries, have not survived from the period up to 1850; Memories of life, such as those of Carl Hagenbeck or P. T. Barnum, come from a more recent time in the menagerie that has not yet been scientifically recorded in a coherent context.

The announcement slips, performance permits and brochures of the early traveling menageries that were kept in the archives alongside the newspapers were occasionally part of exhibitions on the circus or zoo in the late 20th century; Other surviving copies, as well as postcards and prints, were long in the offer of second-hand bookshops and antique and flea markets , so that private collections were formed, which have received increasing attention in recent years in academia and in (often regional) exhibitions.

literature

- Kai Artinger: From the animal shack to the tower of the blue horses. The artistic perception of wild animals in the age of the zoological gardens . Reimer, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-496-01131-9 . (At the same time dissertation, Free University Berlin 1994)

- Eric Baratay, Elisabeth Hardouin – Fougier: Zoo. From the menagerie to the zoo . Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-8031-3604-0 . (Translated from the French " Zoos " by Matthias Wolf)

- Mustafa Haikal : The Lion Factory. CVs and legends . With an afterword by Jörg Junhold, Pro Leipzig, Leipzig 2006, ISBN 3-936508-15-1

- Gerhild Kaselow: The curiosity of exotic animals. Studies on the representation of the zoological garden in painting of the 19th and 20th centuries . Georg Olms, Hildesheim a. a. 1999 (= Studies on Art History; Vol. 129), ISBN 3-487-10858-5

- Thomas Macho: Zoologiken: zoo, circus and freak show . In: Gert Theile (Ed.): Anthropometry. To the prehistory of man made to measure . Wilhelm Fink, Munich (now: Paderborn) 2005 (= Weimar Editions), ISBN 3-7705-3864-1 , pp. 155–178. ( Excerpts can be viewed online at Google Book Search as digital copies on pp. 155–178 )

- Stephan Oettermann : The elephant curiosity. An Elephantographia Curiosa . Syndicate, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-8108-0203-4 .

- Annelore Rieke – Müller, Lothar Dittrich : The lion roars next door. The establishment of zoological gardens in the German-speaking area 1833–1869 . Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 1998, ISBN 3-412-00798-6 , pp. 15ff.

- Annelore Rieke-Müller, Lothar Dittrich: Out and about with wild animals. Wandering menageries between instruction and commerce 1750–1850 . Basilisken-Presse, Marburg 1999, ISBN 3-925347-52-6 .

Web links

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Novella (1828)

- Menageries : Images and sources on the wandering menageries of the 19th century ( PDF ; 11.16 MB)

- Wandermenagerien and zoos

- On the history of British Traveling Menagerie (English)

- The University Of Sheffield National Fairground Archive: Traveling Menageries (English)

- Announcement slip in the British Museum, London (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ MENAGERIE, is one of the most splendid pieces of a splendid and handsome garden. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 20, Leipzig 1739, column 603 f.

- ↑ For the elephant histories see Stephan Oettermann: Die Schaulust am Elefanten. An Elephantographia Curiosa . Syndicate, Frankfurt am Main 1982; Pp. 95-190

- ↑ Franz Irsigler, Arnold Lassotta: beggars and jugglers, prostitutes and executioner. Outsider in a medieval city . Munich 1989, pp. 126-131

- ↑ Eric Baratay, Elisabeth Hardouin-Fougier: Zoo. From the menagerie to the zoo . (2000); P. 68ff.

- ↑ Annelore Rieke-Müller, Lothar Dittrich: On the way with wild animals. Wandering menageries between instruction and commerce 1750-1850 (1999), p. 13f.

- ↑ a b c Eric Baratay, Elisabeth Hardouin – Fougier: Zoo. From the menagerie to the zoo (2000); P. 106

- ↑ Thomas Macho: Zoologiken: Tierpark Circus and Freakshow . (2005) pp. 158f.

- ↑ Stephan Oettermann: The curiosity of the elephant. An Elephantographia Curiosa . Syndicate, Frankfurt am Main 1982; Pp. 157 and 160-164

- ↑ Annelore Rieke-Müller, Lothar Dittrich: On the way with wild animals. Wandering menageries between instruction and commerce 1750–1850 (1999); Pp. 67-73

- ↑ Presentation with photos of the entrance (English)

- ↑ Menagerien , p. 82 (PDF; 13.3 MB); Annelore Rieke-Müller, Lothar Dittrich: Out and about with wild animals. Wandering menageries between instruction and commerce 1750–1850 (1999), p. 101

- ↑ Annelore Rieke – Müller, Lothar Dittrich: The lion roars next door. The foundation of zoological gardens in German-speaking countries 1833–1869 (1998) p. 15f.

- ↑ Annelore Rieke-Müller, Lothar Dittrich: On the way with wild animals. Wandering menageries between instruction and commerce 1750-1850 (1999), p. 39, 62-75

- ^ Max Schmidt, first director of the Frankfurt Zoo , 1827; quoted from Stephan Oettermann: The curiosity of the elephant. An Elephantographia Curiosa . Syndicate, Frankfurt am Main 1982; P. 165

- ↑ Annelore Rieke-Müller, Lothar Dittrich: On the way with wild animals. Wandering menageries between instruction and commerce 1750–1850 (1999); Pp. 24, 27, 30

- ↑ a b c Eric Baratay, Elisabeth Hardouin – Fougier: Zoo. From the menagerie to the zoo (2000); Pp. 107, 108f.

- ↑ Eric Baratay, Elisabeth Hardouin-Fougier: Zoo. From the menagerie to the zoo (2000); P. 57ff.

- ↑ Annelore Rieke-Müller, Lothar Dittrich: On the way with wild animals. Wandering menageries between instruction and commerce 1750–1850 (1999); P. 114

- ↑ Mustafa Haikal: Master Pongo. A gorilla conquers Europe. Transit Buchverlag, Berlin 2013, p. 23, ISBN 978-3-88747-285-6

- ^ The Zoology Museum : George Wombwell

- ↑ Annelore Rieke-Müller, Lothar Dittrich: On the way with wild animals. Wandering menageries between instruction and commerce 1750–1850 (1999), pp. 39–42

- ^ G. Kreutzberg: G. Kreutzbergs Große Menagerie (formerly van Acken) List of all animals in this menagerie together with a short description of the more remarkable ones and their way of life . Görlitz 1835? / 1860; Reprinted by the Leipzig City Museum for History in 1988

- ^ Carl Hagenbeck: Of animals and people . Berlin 1908 ( online at Zeno.org )

- ↑ Here rests in peace : on the death of Karl Krones

- ↑ KD Kürschner: Circus Krone - From the menagerie to the largest circus in Europe. Edited by Circus Krone. Ullstein, Berlin 1998; available online on the life of Karl Krones (1833–1900): Historien om Cirkus Krone ( Memento from July 17, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) (Swedish)

- ↑ Simon Trussler, Clive Barker: New Theater Quarterly 78 . Cambridge University Press 2005; P. 139f.

- ↑ Menagerien , pp. 92, 98, 100 (PDF; 13.3 MB)

- ↑ Annelore Rieke-Müller, Lothar Dittrich: On the way with wild animals. Wandering menageries between instruction and commerce 1750–1850 (1999), p. 33

- ↑ Knie's Children's Zoo

- ↑ Wolfgang Görl: The kiss of the piranha . sueddeutsche.de, August 1, 2008 (accessed February 13, 2011)

- ↑ Elke Hagel: Small animal circus ensures a lot of laughs . schwäbische.de, July 5, 2010 (accessed February 13, 2011)

- ↑ Gerhild Kaselow: The Animal Store pictures of Paul Meyer home . In: dies .: The curiosity of exotic animals. Studies on the representation of the zoological garden in painting of the 19th and 20th centuries . Pp. 57-69

- ↑ The British Museum shows online examples of satirical prints with motifs from the traveling menageries

- ↑ Annelore Rieke-Müller, Lothar Dittrich: On the way with wild animals. Wandering menageries between instruction and commerce 1750–1850 (1999), p. 124

- ^ Goethe's works. Hamburg edition in 14 volumes. Text-critically reviewed and annotated by Erich Trunz . Christian Wegener, Hamburg 1948 ff. Vol. 6, pp. 491-513

- ^ Fritz Bergemann (Ed.): Eckermann. Conversations with Goethe in the last years of his life . Insel Taschenbuch 500, Frankfurt am Main 1981; P. 207f.

- ^ Adelbert von Chamisso's works . First Volume, pp. 248-249; Fifth increased edition 1864

- ↑ rororo music manual in 2 volumes . Reinbek near Hamburg 1973; Volume 2, p. 615

- ↑ Vagrant life. Memories of Vidocq's Man with a Hundred Names . Munich 1920; P. 21ff.

- ↑ Karl May: The treasure in the silver lake . Reprint of the first magazine issue from Der Gute Kamerad , 5th year, issue 1–52, Stuttgart 1890/91, ed. with an introduction by Christoph F. Lorenz on behalf of the Karl May Society. Hamburg 1987. Online as PDF (50 MB)

- ↑ Andreas Meier: own librettos. History of fist material […] . Lang: Frankfurt am Main 1990; P. 62f. ISBN 978-3-631-42874-0

- ^ Michel Foucault: Madness and Society. A story of madness in the age of reason . Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1969, p. 498

- ^ Foucault: Wahnsinn und Gesellschaft (1969), p. 138

- ↑ See, for example, Actual and Warhamped Illustration of a Terrifying and Cruel Sea Dragon and other similar 17th century pamphlets , both on Wikisource

- ↑ Annelore Rieke-Müller, Lothar Dittrich: On the way with wild animals. Wandering menageries between instruction and commerce 1750-1850 (1999), pp. 114-131; P. 133

- ↑ Kai Artinger: From the animal shack to the tower of the blue horses. The Artistic Perception of Wild Animals in the Age of Zoological Gardens (1995), p. 163

- ↑ For example: Well roared, lion - the world-famous Kreutzberg menagerie is a guest in Gerolzhofen in the old town hall . Exhibition from March 5 to April 3, 2005 (Dr. Stephan Oettermann Collection, Gerolzhofen)