Maxillary fracture

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| S02.4 | Zygomatic fracture and maxillary fracture |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

A maxillary fracture (lat. Fractura maxillae , Fractura ossis maxillae , maxilla fracture or jaw fracture of the upper jaw , English maxillary fracture) is a bone fracture of the upper jaw . The upper jaw fracture has typical courses of bone fracture lines that run along weak points in the upper jaw. This fracture can occur outside or inside the row of teeth. The classification of upper jaw fractures, which does not include the upper row of teeth, is based on Le Fort ( Le Fort fractures type I to III).

Anatomical basics

The upper jaw (maxilla) represents the connection between the skull base and the upper row of teeth, which in turn influences the occlusion and the position of the lower row of teeth and the lower jaw . The anatomical structures of the upper jaw are closely related to the oral cavity , the nasal cavity and the eye socket .

The upper jaw is a pair of bones with the shape of a pyramid that is the cornerstone of the facial skeleton. In the vertical direction, the upper jaw connects the cranio - fronto - ethmoidal complex (skull, forehead, ethmoid) located above with the “chewing complex” located below ( palate , alveolar process, teeth , lower jaw ). The upper jaw connects the two zygomatico - orbital complexes in the transverse direction . The shape of the upper jaw roughly corresponds to a 5-sided pyramid, the base of which is the lateral nasal wall. The remaining four sides are the orbital floor (above), the alveolar ridge (below), the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus (anterior) and the anterior surface of the pterygopalatine fossa (posterior; alar palatal fossa ).

Causes of the maxillary fracture

Maxillary fractures often result from blunt force, which acts with high energy on the facial skeleton. Typical causes for this trauma are traffic accidents (car, motorcycle, bicycle), sports accidents, physical disputes (very often kicks), falls from a great height and falls . Upper jaw fractures are less common as a result of gunshot wounds or hoof kicks .

frequency

Of the facial fractures, around 6 to 25% are maxillary fractures. Because of the small number of cases and the different counts of the number of cases, depending on whether the survey is carried out in a trauma surgery clinic, a dental clinic or an orthodontic clinic, the distribution frequencies of the various sources differ greatly.

classification

The maxillary fracture is one of the midface fractures . These are divided into central and lateral midface fractures. The lateral midface fractures include the zygomatic bone fracture , the zygomatic arch fracture, and the orbital floor fracture . Central midface fractures include the three types of Le Fort fracture , which are transverse fractures of the upper jaw outside the row of teeth. The Le Fort fracture is also known as the craniofacial detachment of the midface .

Le Fort Fractures

The Le Fort fractures are named after René Le Fort (1869–1951), a French surgeon from Lille , who introduced today's most common classification of maxillary fractures with the typical bone fracture lines in the transverse direction above the rows of teeth.

Le Fort published his work on the classification of maxillary fractures in 1901. In his studies, Le Fort exposed cadaveric skulls to various blunt acts of violence (metal ball on a long pendulum) from different directions and with different intensities. Then he examined the injuries and typical courses of the fault lines.

Le Fort found three standard maxillary fracture patterns that accounted for the majority of the fractures:

- the horizontal Le Fort I fracture ,

- the pyramidal Le Fort II fracture ,

- the transverse Le Fort III fracture .

While the Le Fort I and Le Fort II fractures are strictly limited to the central midface, the Le Fort III fractures extend across both the central and lateral midface.

Le Fort I fracture

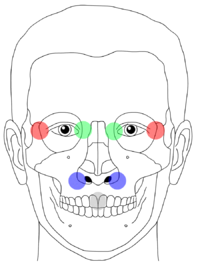

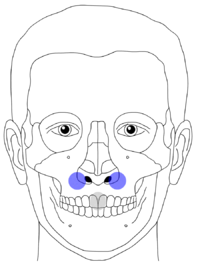

The central midface fracture of the type Le-Fort-I (referred to as Le-Fort-I for short ) is a horizontal fracture of the upper jaw (see picture: red line). The alveolar process of the upper jaw is separated from the rest of the upper jaw and skull. These transverse fractures of the upper jaw with horizontal separation of the alveolar process (lat. Processus alveolaris maxillae) run at the level of the floor of the nasal and maxillary sinuses . The bone fragment is reminiscent of a full maxillary denture .

In the horizontal Le Fort I fracture, the fracture line extends from the nasal septum to the lateral edge of the piriform aperture , horizontally just above the tips of the roots of the maxillary teeth; it then crosses below the zygomaticomaxillary suture (the bone suture between the maxilla and the zygomatic bone) and crosses the sutura pterygomaxillaris and then the lateral and medial pterygoid processes (left and right halves of the face).

For the palpatory diagnosis it is important that the break line runs through the nasal aperture (to the right and left of the nostril - movement and the associated pain can be triggered), but not through the inner or outer corner of the eye.

The fracture is caused by horizontal, slightly downwardly directed forces acting on the alveolar process of the upper jaw.

Le Fort II fracture

The Le Fort II fracture is a central midfacial fracture with a pyramidal upper jaw detachment (pyramidal fracture ) of the upper jaw mass. The fracture line runs along or below the frontomaxillary suture (with or without involvement of the nasal skeleton), through the maxillary frontal process, along the medial wall of the orbit (medial corner of the eye), through the lacrimal bone, through the floor of the orbit and the lower edge of the orbit the infraorbital foramen or close to it, obliquely downward through the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus . The fracture line continues under the zygomatic bone , along the pterygomaxillary fissure and through the medial and lateral pterygoid lamina.

The Le Fort II fracture separates the nasoethmoid block from the rest of the skull. It can occur on both sides (classic form) or on one side.

This fracture is caused by forces acting on the lower or middle part of the upper jaw.

Le Fort III fracture

The centrolateral midface fracture type Le Fort III is a complete demolition of the midface from the base of the skull . This high detachment of the maxilla lies in the upper part of the midface.

The entire upper jaw, sometimes also other bones, i.e. the entire midface, are detached from the craniofacial skeleton in the Le Fort III fracture . This is why this transverse Le Fort fracture is also referred to as a craniofacial separation (tear off of the face from the cranium ).

The fracture margins run through the nasal skeleton (sutura nasofrontalis and sutura frontomaxillaris), along the medial wall of the orbit (medial corner of the eye), through the ethmoid bone ( ethmoid bone ). The thick sphenoid bone ( sphenoid bone ) prevents the fracture line from continuing backwards into the optic canal. The fracture line continues along the orbital floor, further superior-lateral to the lateral wall of the orbit (distal corner of the eye), through the zygomaticofrontalis suture and the zygomatic arc.

If the zygomatic bone and / or the zygomatic arch are involved, one speaks of a zygomatico-maxillary fracture. Unilateral Le Fort III fractures are also possible.

Within the nose, the fracture runs through the base of the ethmoid bone , through the vomer and through the connection of the lateral and medial lamina of the pterygoid process of the sphenoid bone with the base of the sphenoid bone .

This fracture is caused by forces acting on the upper jaw or the bridge of the nose.

Critique of the Le Fort classification

In today's clinical practice, the Le Fort classification proves to be an over-simplification of maxillary fractures. The idealized forces to which Le Fort exposed the skull in his experiments often do not correspond to the actual, complex forces. The energy that acts on the midface during a traffic accident is much stronger than the forces that Le Fort used in his experiments on cadaver skulls in 1901.

Another criticism of the Le Fort classification is that some fractions are not taken into account, e.g. B. sagittal fractures, zygomatic fractures and zygomatic arch fractures.

Small maxillary fractures are not included in the Le Fort classification. In these fractures, only a small, isolated fragment is blasted off (caused by weaker forceful effects that are limited to a small area), for example by a hammer blow. The alveolar process, the anterior maxillary sinus wall or the nasomaxillary suture are typical locations for this type of fracture.

In addition, submental forces ("blow to the chin") that are directed upwards can lead to severe, isolated, vertical fractures through one of the horizontal support structures of the upper jaw (e.g. alveolar ridge, infraorbital bone edge = rima infraorbitalis, zygomatic arch). These fractures are also not covered by the Le Fort classification.

Today, maxillary fractures are usually a combination of different Le Fort types (mixed types), unilateral fractures and atypical fractures. The fault lines often deviate from the classic courses described. If the facial skull is subjected to very strong violence, lower jaw fractures and / or skull fractures can occur in addition to the upper jaw fractures .

Guérin's fractures

A lesser known, older classification of the upper jaw fracture goes back to the Paris surgeon Alphonse Guérin (1801–1866) (published in 1866). This fracture is known as the Guerin fracture . The fracture is a transverse fracture of the upper jaw and runs horizontally through the piriform aperture (the anterior border of the bony nasal cavity). It largely corresponds to the Le Fort I fracture .

Wassmouth fractures

There is also an overlap in the classification between the Waßmund fractures ( Martin Waßmund , German oral surgeon, 1892–1956) and the Le Fort fractures . Both are midface fractures. The Waßmund fractures of type II correspond to the Le Fort fractures of type II. The Waßmund fractures of type IV correspond to the Le Fort fractures of type III. The Waßmund fractures of type III are also similar to the Le Fort fractures of type III.

| Le-Fort-I | Guerin fracture |

| Le-Fort-II without involvement of the nasal skeleton | Waßmund fracture type I |

| Le-Fort-II | Waßmund fracture type II |

| Le-Fort-III without involvement of the nasal skeleton | Waßmund fracture type III |

| Le-Fort-III | Waßmund fracture type IV |

Sagittal fracture of the upper jaw

In addition to Le Fort fractures , isolated sagittal fractures of the upper jaw are much less common. This fracture runs sagittally (from front to back through the upper jaw). The break line usually runs close to the palatal suture (sutura palatina transversa).

Alveolar process fractures

Fractures within the row of teeth are often combined with alveolar fractures and / or tooth fractures .

Modern classification of midface fractures

Today's classification of midface fractures differentiates between lateral (cheekbone fracture ), centrolateral ( Le Fort III fracture ) and central midface fracture ( Le Fort I fracture , Le Fort II fracture , nasal bone fracture and sagittal maxilla fracture). However, this newer classification has not completely supplanted the older Le Fort classification.

diagnosis

Examination and clinical diagnosis

The external detection of facial fractures is usually made more difficult by the fact that, after serious accidents, the shape and position of the facial bones can only be guessed at due to massive swellings ( edema ) of the facial soft tissues, bruises , abrasions, extensive bleeding and bruises ( hematomas ). The enormous swelling of the face after severe trauma can often make this classic clinical assessment impossible.

Possible symptoms of a maxillary fracture are abnormal mobility of the otherwise rigid maxilla, dislocation of the bone fragment, bone crunching ( crepitation ) when moving the bone fragment, hematomas , swellings , sensory disorders (especially infraorbital nerve ), sprain pain, bleeding , occlusion disorders . In the percussion of the teeth a dull knocking sound can be heard.

Clinically, the diagnosis is made by causing pain and controlling mobility with the slight movement of the upper jaw fragment. To do this, the upper front teeth (the two large incisors - in the picture: gray point) are gently shaken with the thumb and index finger. The other hand feels with thumb and forefinger for a possible movement at the typical course points of the break lines.

(Image description: Le Fort I: mobility only on the blue points; Le Fort II: mobility only on the green points; Le Fort III: mobility on the green and red points)

Midface mobility can be tested by firmly grasping and jiggling the upper central incisors while holding the patient's forehead with the other hand to stabilize the head. The size and location of the mobile bone fragment can tell the doctor what type of Le Fort fracture it is. However, errors can also occur if the bone fragment is firmly impacted (wedged) in its dislocated position due to the high force applied and there appears to be no bone mobility.

Periorbital swellings could indicate a Le Fort II or Le Fort III fracture .

A thorough nasal and intraoral examination should be performed. In Le Fort II fractures , the nasal bones are typically very mobile, along with the rest of the pyramidal upper jaw fragment. On intranasal inspection, fresh or old bleeding, septal hematoma, or rhinorrhea (nasal discharge) from cerebrospinal fluid can be seen.

During the intraoral examination, the intact occlusion is checked, the condition of the individual teeth, the stability of the alveolar process and the hard palate . Watch out for injuries to the soft palate. In addition, the contour of the upper jaw is scanned intraorally with the fingers in order to detect possible bony damage to the anterior maxillary sinus wall or to the zygomaticomaxillary or nasomaxillary pillars.

In the event of severe accompanying injuries with obstruction of the airways or traumatic brain injury , the examination of the upper jaw and facial bones must be postponed until the more serious injuries have been controlled.

Localized swellings or bruises may be related to the fracture line. Periorbital swelling may indicate a Le Fort II or III fracture .

A shift back of the fractured middle face results in a flattened face shape, which is referred to in the Anglo-Saxon specialist literature as dish-face (also pan-face , uncommon translation: plate face ). This facial deformity occurs after large Le Fort II or Le Fort III fractures , but is initially masked by the facial swelling. The fractured upper jaw segment is shifted back and down. This can lead to early contacts in the molar area, accompanied by an anterior open bite. In severe cases, partial obstruction of the upper airway can make breathing difficult. In these cases it may be necessary to decompress (reduce) the nasal floor and the hard palate as quickly as possible in order to move the dislocated bone fragment forwards again and thus clear the airways again.

In Le Fort II fractures , the nasal bones are typically very mobile; they move together with the freely floating, pyramidal bone fragment of the upper jaw. In Le Fort III fractures , the fracture line also runs through the lateral orbital margin and the zygomatic bone.

eyes

In the eye socket, the firmness of the edge of the eye socket and the floor of the orbit is examined, as well as the visual acuity, extraocular movement, the position of the eyeball and the intercanthal distance (distance between the corners of the eyelid - eyelid ). Impairments of the visual acuity can indicate damage to the optic canal, damage to the eyeball or the retina or to other neurological problems. Impaired mobility of the eyes or enophthalmos can be signs of a fracture of the orbital floor (blow-out fracture). If the intercanthal distance is increased, consider a displacement of the bone in the area of the frontomaxillary suture or the lacrimal bone or a tear in the medial canthal ligament.

Any existing photos of the patient that were taken before the accident could be helpful for planning the operation and advising the patient.

Occasionally, when asked, the patient states that the corresponding pain in the upper jaw (at the root of the nose; outer corner of the eye) is triggered by the lower jaw's own pressure on the upper jaw when biting.

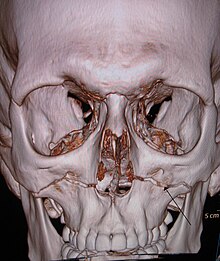

X-ray diagnosis

The X-ray examination is carried out with an orthopantomography and with an overview of the upper jaw (film intraoral, horizontal, bite exposure, X-ray 90 ° or 65 ° (to the bite plane) from above - extraoral). The occipito-nasal image of the skull (semi-axial setting) also shows the entire midface well (orbital margins, frontozygomatic suture, zygomatic bone, zygomatic arch, paranasal sinuses).

Simple x-rays are indicated for the first examination. This also includes a submental image with a vertical beam path and lateral images, as well as a control image of the cervical spine. X-rays of the maxillary sinuses show the zygomatic arch and the nasal bones at the same time. In order to get a clear idea of the three-dimensional anatomy and extent of the fracture, the X-ray images of the various projections must be compared with one another.

With the computed tomography (CT), the possibilities for diagnostic imaging of the upper jaw fractures have significantly improved. The CT often shows the course of the fracture more precisely and helps with surgical planning.

Differential diagnosis

A skull fracture must always be considered in the differential diagnosis , which must be ruled out radiologically. A skull fracture is much more serious than a fracture of the upper jaw. Often both perform together. Eyeglass hematoma can be a sign of skull base fractures, as can bleeding from the nose and ear. It must be clarified whether the blood has cerebrospinal fluid .

Treatment of the skull fracture has priority, while treatment of the maxillary fracture in severely injured multiple trauma often has to wait 1–2 weeks. After the general condition has stabilized, a CT scan of the facial skull is usually carried out to diagnose a midface fracture.

Accompanying injuries

Maxillary fractures often occur with severe trauma. Therefore, further damage to the patient should be researched. Possible obstructions of the airways can be acutely life-threatening. Because of the involvement of the orbit, damage to the eyes must be examined ( enophthalmos - sunken eye; diplopia - double vision - especially when looking upwards). Impaired skin sensitivity under the eye indicates damage to the infraorbital nerve . In the case of high maxillary fractures (Le-Fort-III), the involvement of the lamina cribrosa sometimes results in damage to the olfactory nerves with anosmia and nasal liquor discharge . Hearing and tooth occlusion should also be examined.

Functional failures can provide clues for the localization of the fracture - e.g. B. respiratory disorders, reduced vision, cranial nerves, occlusion or hearing. Changes in consciousness or loss of consciousness can be signs of an intracranial injury.

therapy

The therapy of the maxillary fracture is carried out by reduction , fixation, retention and immobilization . Midfacial fractures usually require surgical treatment by an oral, maxillofacial, and facial surgeon, ENT specialist or plastic surgeon.

The displaced fragment is repositioned and fixed by means of mini-plate osteosynthesis ( osteosynthesis ). Before the advent of plate fixation, fixation was carried out using wire fixation, which also produced good results.

Initial treatment

The accident care must first ensure the vital functions . If the airway cannot be exposed, the dislocated, impacted upper jaw fragment must be repositioned as an emergency. If this is not possible, a tracheostomy may need to be performed. The emergency splinting for a longer transport can be done with a ruler, on which the patient bites with his molars and the ends of which protrude on both sides at the corners of the mouth. These ruler ends can be temporarily fixed upwards - with a bandage that is tied over the skullcap.

Since maxillary fractures are very often caused by traffic accidents, they are often accompanied by other potentially life-threatening injuries. The diagnosis of the maxillary fracture is then not in the foreground during the initial phase of treatment. Because of the severity of the maxillary fractures and other injuries, these patients must be intubated very often to ensure breathing. A midface fracture is always treated as an inpatient, at least in the initial phase.

If the lower jaw is displaced back and there are associated breathing problems, rapid, provisional decompression of the upper jaw, especially the palate, must be carried out. To do this, the compressed fragment is pulled forward using pliers and hooks, while the compressed area in the hard palate is decompressed again.

surgery

Surgical treatment tries to remove the defects and to achieve an aesthetic reconstruction of the face. To do this, unstable bone fragments are attached to stable parts of the skull. An important therapy goal is the restoration of normal tooth occlusion, the chewing function and the speech function.

Since the occlusion must be checked intraoperatively, normal intubation via the mouth is not an option. Instead, nasal intubation is used. A rare intubation technique is submandibular intubation. After intubation through the mouth, the tube is led out of the oral cavity through an surgically created opening in the anterior floor of the mouth in the submental area.

Reduction

Displacement of fragments due to muscle pull, as occurs particularly in fractures in the extremity area, cannot be observed in upper jaw fractures because the other end of the muscles that attach to the upper jaw is predominantly attached to the skin. In this way, there is no displacement of fragments due to muscle pulling, and repositioning is not made difficult by muscle pulling. However, fragments are often displaced due to the great force of force during the fracture and the fracture margins often stand in the way of reduction because they are strongly jagged and have a complicated three-dimensional course.

Technique of operative fixation

Mini plates, wire suspension

Operative access:

- for Le-Fort-I : oral vestibule

- for Le-Fort-II : medial eyebrow, infraorbital or transconjunctival, oral vestibule

- for Le-Fort-III : medial and lateral eyebrows

A stable splint (plate osteosynthesis) of the fragment is aimed for.

The best cosmetic results with regard to the scars are achieved with two-layer seam closure to reduce the tension on the skin and thus achieve a smaller scar. The sutures are removed after 5-10 days.

Maxillo-mandibular fixation

Maxillo-mandibular fixation (MMF) of the rows of teeth of the lower and upper jaw may be necessary in the treatment of the upper jaw fracture. The established name of "intermaxillary fixation" (IMF) is incorrect because it is not two maxillae that are connected, but the mandible and the maxilla. Correctly, the name is increasingly changing to Maxillo-Mandibular Fixation. This fixation is usually carried out intraoperatively after the fragments have been repositioned and fixed. The fixation splints the fractured on the healthy jaw. The rubber rings stretched between the upper jaw and lower jaw are removed to allow the anesthetist access to the patient's throat in the event of complications, for example if the patient vomits.

For the time in which the maxillo-mandibular fixation is worn (approx. Three to eight weeks), nutrition must be ensured via a nasal feeding tube. A vomiting ( emesis ) during fixation poses an increased risk of aspiration of vomit. In an emergency, the elastic bands connecting the upper and lower jaws can be cut to open the mouth. The patients therefore always have to carry scissors with them during the fixation period.

A mandibulo-maxillary fixation (lacing) is particularly necessary if the upper jaw fragment could not be securely fixed to the skull.

Mandibulo-maxillary fixation is only possible if the fragment is correctly repositioned and aligned. If the complete repositioning of the upper jaw fragment does not succeed surgically, an additional Le Fort I osteotomy can be used to restore the patient's proper occlusion.

Complications

Permanent deformities can remain as complications after maxillary fractures.

Despite proper healing "on the X-ray", damage to neurovascular bundles can occur - the supraorbital nerve, infraorbital nerve, facial nerve (r. Frontalis). There is a possibility of subsequent infections, which are favored by extensive soft tissue defects, hematomas, open fractures, and comminuted fractures. Incorrect adhesion occurs more frequently than non-adhesion of the bone fragments. Bone grafts may be required to prevent this from happening.

Early surgical interventions have the best prospects for good functional and aesthetic results.

Replacement osteotomies

In osteotomies to adjust the occlusion or the facial skull in the case of maxillary facial deformities (orthognathic surgery), the division of the bone is carried out analogously to the break lines according to Le-Fort-I ( Le-Fort-I osteotomy - for retroposition of the upper jaw, e.g. after deformations as a result of an operated LKG column ; possibly in combination with a velopharyngoplasty) or Le-Fort-III .

literature

- Karl Heinz Austermann: Fractures of the facial skull. In: N. Schwenzer, M. Ehrenfeld (Hrsg.): Tooth-mouth-jaw medicine. Volume 2: Special Surgery. Thieme Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-13-593503-5 .

- Andreas Neff, Christoff Pautke, Hans-Henning Horch: Traumatology of the facial skull. In: Heinz-Henning Horch (Ed.): Oral and maxillofacial surgery . Urban & Fischer at Elsevier, 2006, ISBN 3-437-05417-1 .

- Jan Behring: cause, therapy and consequence of central midface fractures . Dissertation . Hamburg 2004.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e H. Horch: Oral and maxillofacial surgery. (= Practice of Dentistry. Volume 10). 4th edition. Urban & Fischer-Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-437-05417-1 .

- ^ René Le Fort: Étude expérimentale sur les fractures de la mâchoire supérieure . In: Rec Chir Paris . tape 23 . Paris 1901, p. 208-227 .

- ↑ René Le Fort: Experimental study of fractures of the upper jaw . In: Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery . tape 50 . Paris 1972, p. 497-506 , PMID 4563382 (Original title: Étude expérimentale sur les fractures de la mâchoire supérieure . Translated by P. Tessier).

- ↑ Central midface fracture . DocCheck Community GmbH, accessed on October 11, 2018 .