President of the Republic of Tunisia

|

President of the Republic of Tunisia |

|

|

|

| Standard of the President | |

|

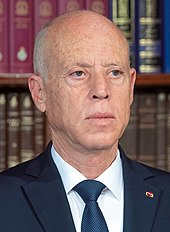

Acting President Kais Saied since October 23, 2019 |

|

| Official seat | Palais de la République, Tunis |

| Creation of office | July 25, 1957 |

| Last choice | October 13, 2019 |

| website | www.carthage.tn |

The President of the Republic of Tunisia has been the head of state of Tunisia since the Republic was founded on July 25, 1957 . He is the head of the executive branch and runs the country alongside the Prime Minister , who is formally the head of government. The President is also the Commander in Chief of the Tunisian Armed Forces . Up until the revolution in Tunisia in 2010/2011 and the flight of President Ben Ali , the Tunisian presidents ruled largely autocratically and in fact without a separation of powers, not only in charge of the executive power , but also in the legislative process and the judiciary . The day after Ben Ali's escape, the previous President of the Chamber of Deputies became interim president, who was replaced by Moncef Marzouki , also on an interim basis, after the election to the Constituent Assembly of Tunisia in 2011 . Both had poor skills; Political power lay with the constituent assembly , which passed a new constitution on January 26, 2014 , in which the position of the president was reorganized as the holder of executive power, who is opposed to a strong parliament ( semi-presidential system of government ). This President was first democratically elected in an election by citizens on November 23 and December 21, 2014 . In the runoff election on December 21, Beji Caid Essebsi prevailed against incumbent Moncef Marzouki and from December 31, 2014 until his death was the first president of Tunisia to be freely elected by the people.

Since this office has existed, it has been held by five people. The first incumbent was Habib Bourguiba , who held the post until the bloodless coup on November 7, 1987. Since then it has been run by Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali . After his escape from the country on January 14, 2011, the office was held provisionally by Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi . On January 15, 2011, the President of the Chamber of Deputies, Fouad Mebazaa , took over the office. All four were members of the Rassemblement constitutionnel démocratique or its predecessor organizations Neo-Destour and Parti Socialiste Destourien . On November 23, 2011, the chairman of the CPR Moncef Marzouki was elected interim president of the country by the constituent assembly.

prehistory

The nationalist Destur party , founded in 1920, called for a constitution to be drawn up early on, but this should not affect the then existing monarchy . Even after founding the successor party Néo-Destour in 1934 under the leadership of Habib Bourguiba , this attitude did not change.

The party congress in November 1955 called for elections to a constituent assembly to be held as soon as possible and for a new form of government to be built on the basis of a constitutional monarchy that respected the sovereignty of the people and the separation of powers .

The Husainid family that ruled Tunisia at that time, however, was largely of Turkish origin. It did not identify with the country; the Tunisians viewed them as rulers who collected high taxes and used foreign armies to put down insurrections.

On December 29, 1955, Lamine Bey signed the decree calling for the election of the constituent assembly. Habib Bourguiba formed the country's first government as prime minister. The privileges of the Husainids were subsequently abolished, and the royal family's economic management was subordinated to the Ministry of Finance. In the Néo Destour party, the view that the Beys at the head of the state represented a break in national unity became more and more accepted .

The proclamation of the republic was thus decided and was originally to take place on June 1, 1957, the second anniversary of Bourguiba's return to Tunisia. However, this was initially thwarted by a crisis surrounding the suspension of French economic aid. An extraordinary session of the Constituent Assembly was finally called for July 25 in the throne room of the Bardo Palace . The monarchy was abolished by unanimous decision and a republican form of government was introduced; power was taken over by Neo-Destour alone. The Bey's possessions were confiscated and used to pay off national debts. Bourguiba was entrusted with the role of president until a new constitution was adopted.

Position of the President before the Revolution

In accordance with the constitution in force until 2011, the president was elected by direct universal suffrage for a period of five years. After the constitutional amendment of 2002 he was re-elected indefinitely. Before that, a person could only hold four terms, later three terms, but between 1975 and 1988 the presidency was for life. The international media, human rights organizations, the French Human Rights Advisory Council and the American government agreed that the election of the president was not to be classified as free because the ruling party Rassemblement constitutionnel démocratique exercised extensive control over the media and opposition groups were suppressed.

Presidential election

Requirements for candidacy

Article 40 of the constitution, which was in force until 2011, allowed every citizen of Tunisia who professes Islam , and even those whose parents and grandparents were Tunisian citizens without interruption, to run for the presidency. The candidate had to be between 40 and 75 years old (70 years between 1988 and 2002), with the cut-off date being the date on which he submitted his candidacy. He had to have all civil and political rights.

In addition, he had to leave 5000 dinars as bail, which he only got back after the elections if he could get at least 3 percent of the vote. In order to submit his candidacy, the candidate had to submit a birth certificate, which could not be older than one year, and the citizenship certificates of himself, his parents and grandparents; the Ministry of Justice had to issue these documents.

The deadline for candidacy was the second month before the presidential election. The candidacy had to be supported by at least thirty members of the Tunisian parliament or presidents of the municipal councils, whereby each person entitled to support could only give his support to one potential candidate. This provision was introduced in 1976 after Chedly Zouiten announced his candidacy against Bourguiba in the 1974 elections. The candidacy was subsequently accepted by the Constitutional Council; the body had existed since 1987 and consisted of nine members, four of whom were appointed by the President himself and two by the President of the Chamber of Deputies. Only the President himself could call the Constitutional Council; the decisions of this body were judgments bearing the seal of the president. The Constitutional Council decided on the validity of the candidacy with a simple majority behind closed doors.

Before the constitutional reform of 2002, the decision on the validity had been made by a body made up of the President of Parliament, the Mufti of Tunisia, the first President of the Administrative Court, the first President of the Court of Appeal of Tunis and the Attorney General of the Republic. Once the candidacy had expired, it was no longer possible to withdraw a candidacy. The Constitutional Council also announced the results of the elections and answered requests that could be made in accordance with the electoral code.

Until the 2011 revolution, only the ruling party Rassemblement constitutionnel démocratique of then President Ben Ali had the necessary number of MPs to deliver the declarations of support for the presidential candidate. None of the opposition groups had this option. In order to nevertheless enable formal pluralistic elections, a constitutional law was passed on June 30, 1999, which exceptionally changed Article 40 for the 1999 elections . Candidates were also admitted who were the leaders of a political party that had existed for at least five years on election day and held at least one seat in parliament. Ahmed Néjib Chebbi from the Parti Démocratique Progressiste and Mohamed Harmel from the Mouvement Ettajdid were therefore excluded from the election. In 2003 was again exceptionally a constitutional law decided that allowed the five opposition parties represented in Parliament to nominate a candidate of their choice for the election of 2004. The candidate no longer had to be the party chairman, but it was required that he had to be a member of his party for at least five years on the day his candidacy was submitted.

The constitution was changed again for the 2009 elections. Party leaders who had to be leaders of their party for at least two years were now entitled to stand as candidates. This again ruled out Ahmed Néjib Chebbi, who had previously called for the need to collect declarations of support to be abolished.

Course of the election campaign and the vote

In accordance with the 2011 constitution, the election had to be held within the last 30 days of the president's expiring term. If no candidate received an absolute majority in the first ballot, the two candidates with the largest proportion of the votes cast ran against each other in a runoff that had to be held two weeks later. If it was impossible to organize an election in the required time frame, be it because of war or acute threat, the mandate of the incumbent president was extended by the Chambre des députés until it was possible to hold an election. The election campaign begins two weeks before the election date and ends 24 hours before.

During the election campaign , each candidate had the same space for advertising posters. Candidates were also allowed to use the state radio for their election campaigns, with requests for airtime to be submitted to the public broadcasting authorities within five days of the announcement of the list of candidates by the Constitutional Council. The date and time of the advertising broadcasts were determined at random by the control authorities, with each candidate being entitled to the same broadcasting time within the two weeks before the election. On November 7, 2008, President Ben Ali announced that the Broadcasting Council would review the candidates' programs to ensure that no applicable laws were being violated and, if necessary, prevent them from being broadcast. A candidate could have taken legal action against it.

Grants were granted to each candidate by decree. The amount of this campaign funding was based on the votes obtained in the elections. Half of the grant was paid after the Constitutional Council confirmed the candidacy. The second half was paid out if the candidate won at least 3% of the votes cast nationwide. Each candidate had the right to be present at each election office through a delegate in order to monitor the election process.

Previous ballots

The first presidential and parliamentary elections took place on November 8, 1959. Subsequent elections were traditionally held on Sundays.

Bourguiba, benefiting from his aura as the leader of the independence movement, was the only candidate in all elections up to 1974. He was able to unite 91 to 99.85 percent of the votes in each case. On September 10, 1974, a second candidate for the office of president announced his candidacy for the first time: Chedly Zouiten , chairman of the Jeune chambre économique de Tunisie , announced his decision in a press release. However, she was immediately condemned by the members of his association and the electoral commission did not consider his candidacy. Bourguiba was later appointed president for life .

In 1987, Ben Ali took power in a bloodless coup and was confirmed in the following presidential elections without ever admitting an opposing candidate with a chance. It was not until 1994 that a second attempt was made to put up an opponent for the incumbent president. However, Moncef Marzouki , former chairman of the Tunisian Human Rights League , was unable to collect the necessary number of statements of support. He was later arrested and was no longer allowed to receive a passport. As a result, constitutional laws were passed temporarily suspending Article 40 of the Constitution so that opposing candidates in the 1999, 2004 and 2009 elections could apply to the Supreme Court.

After the resignation of the previous President Ben Ali on January 14, 2011, there should be new elections for the office of head of state by April 2011, which did not take place as a new constitution should first be drawn up, which enables a pluralistic democracy.

| Ballot | candidate | Result | Party affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|

| November 8, 1959 | Habib Bourguiba | 91% | Neo-Destour |

| November 8, 1964 | Habib Bourguiba | 96% | Parti Socialiste Destourien (PSD) |

| 2nd November 1969 | Habib Bourguiba | 99.76% | Psd |

| 3rd November 1974 | Habib Bourguiba | 99.85% | Psd |

| April 2, 1989 | Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali | 99.27% | Constitutional Democratic Collection (RCD) |

| March 20, 1994 | Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali | 99.91% | RCD |

| October 24, 1999 | Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali | 99.45% | RCD |

| Mohamed Belhaj Amor | 0.31% | Parti de l'Unité Populaire (PUP) | |

| Abderrahmane Tlili | 0.23% | Union Démocratique Unioniste (UDU) | |

| October 24, 2004 | Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali | 94.49% | RCD |

| Mohamed Bouchiha | 3.78% | PUP | |

| Mohamed Ali Halouani | 0.95% | Mouvement Ettajdid | |

| Mounir Béji | 0.79% | Parti Social-Libéral (PSL) | |

| October 25, 2009 | Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali | 89.62% | RCD |

| Mohamed Bouchiha | 5.01% | PUP | |

| Ahmed Inoubli | 3.80% | UDU | |

| Ahmed Brahim | 1.57% | Mouvement Ettajdid | |

Criticism of the legislation

Criticism of the electoral laws, which ran until 2011, was voiced by both the Tunisian opposition and the international press. As a rule, the incumbent had a strong voter base, was supported by the administration and was therefore able to dispose of greater human and financial resources than his competitors. The opposition consisted of parties that were exposed to frequent internal crises and found it difficult to develop a credible program. The restrictive and frequently changing requirements for the candidacy prevented a leader from developing in the opposition. The first partially pluralistic presidential elections in Tunisian history did not take place until 1999. The foreign press criticized that the two opposing candidates Mohamed Belhaj Amor and Abderrahmane Tlili had expressed their support for the policies of President Ben Ali.

The reforms carried out in the past have therefore not reduced the incumbent's influence on the presidential elections. In the history of Tunisia, the elections have never posed a challenge to the power elite.

With those in power having a de facto monopoly over the media, the election campaigns were very uneven. While the candidates had the same airtime for their commercials, the state media was otherwise dominated by extensive coverage of government policies and the activities of the president.

Candidates were strictly forbidden from campaigning in the private or foreign mass media. Violation of this ban would have resulted in a fine of 25,000 dinars. Political debates on television were unknown in Tunisia, and when the elections were reported on Tunisian television, the reporting consisted primarily of an invitation to vote.

Furthermore, the size of the electoral districts and the number of polling stations presented a hurdle for the challengers in the election. As a rule, only the incumbent had the means to conduct a real election campaign, at the same time the high number of polling stations made it almost impossible to get one carry out effective control of the ballot.

Term of office

List of Presidents of the Republic of Tunisia

The following people have held the presidency so far:

| # | image | Surname | Taking office | Resignation | Political party |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Habib Bourguiba | July 25, 1957 | October 22, 1964 | Neo-Destur | |

| October 22, 1964 | November 7, 1987 | Psd | |||

| 2 | Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali | November 7, 1987 | February 27, 1988 | Psd | |

| February 27, 1988 | January 14, 2011 | RCD | |||

| - |

Mohamed Ghannouchi (acting) |

January 14, 2011 | January 15, 2011 | RCD | |

| 3 |

Fouad Mebazaa (interim) |

January 15, 2011 | January 18, 2011 | RCD | |

| January 18, 2011 | December 12, 2011 | Non-party | |||

| 4th |

Moncef Marzouki (interim) |

December 12, 2011 | December 31, 2014 | CPR | |

| 5 |

Beji Caid Essebsi |

December 31, 2014 | July 25, 2019 | independent (until Nidaa Tounes took office ) | |

| 6th |

Mohamed Ennaceur (interim) |

July 25, 2019 | 23 October 2019 | Nidaa Tounes | |

| 7th |

Quays Saied |

23 October 2019 | officiating | independent |

Swearing in

The swearing-in of the president took place in front of the parliament until 2011, the two chambers of which met for a joint session on this occasion. The oath that the president had to take read as follows: I swear by God Almighty to preserve the independence of the fatherland and the inviolability of its territory, to respect the constitution and its legislation and to diligently pursue the interests of the nation .

Limitation of terms of office

According to the constitution in force until 2011, the president was elected for a term of five years in general, free, direct and secret elections with an absolute majority of the votes cast. The incumbent president could be re-elected, whereby the number of re-elections in the last version of the constitution was unlimited.

According to Article 40 of the 1959 constitution, the president could only be re-elected three times, which limited the number of terms to four consecutive mandates.

The first incumbent Habib Bourguiba was elected four times in 1974. In September 1974, the ninth party congress of the Parti Socialiste Destourien approved Bourguiba's application for the presidency for life. On March 18, 1975, Parliament passed Constitutional Law No. 75-13, which contained paragraph 2 of Article 40, exceptionally and taking into account the outstanding merits of the chief fighter Habib Bourguiba, who freed the Tunisian people from the yoke of colonialism and a modern, sovereign nation founded , changed. Article 51 (later Article 57) was also amended so that the Prime Minister would take over his duties in the President's absence.

In 1976 Prime Minister Hédi Nouira had Article 39, Paragraph 3, which was not abolished but only suspended by the 1975 law, changed so that the mandate was unlimited.

After he came to power in 1987, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali promised to restore the republican idea and belief in its institutions . With the law of July 25, 1988, Articles 57 and 40 were amended to limit the number of terms of office to three instead of four. After Ben Ali, like Bourguiba before, had exhausted the highest number of possible terms of office, the constitutional amendment of May 26, 2002 reintroduced the unlimited mandate, as had previously been done by Hédi Nouira . At the same time, the maximum age of the candidate was raised to 75 years. This step was criticized as delivering the constitution to the coincidences of biology , as an addition to the republic or as a disguised coup .

Succession planning

In the event that the office of president became vacant, Paragraph 51 of the constitution was originally formulated to the effect that the government would select one of its members to temporarily assume the office of president. She had to inform the chairman of parliament of the election without delay. A new president should be appointed within five weeks for the remainder of the term of office. President Bourguiba opposed this formulation because it would not have allowed him to choose his successor himself. The problem of succession became particularly acute after the President suffered a heart attack on March 14, 1967. On November 29, 1969, a constitutional law was finally passed, which changed Article 51 so that the Prime Minister should automatically take over the office of President if he was prevented. In June 1970, Bourguiba commissioned a commission from his Parti Socialiste Destourien to develop several scenarios for automatic succession in the office of head of state. From the options of automatic succession by the prime minister, by the speaker of parliament or a vice-president to be elected, the first solution remained. The constitution now stipulated that the office could become vacant through the death or resignation of the president, but also through absolute hindrance . However, there was no definition of which organ should determine the unconditional prevention . The then Prime Minister Ben Ali took advantage of this loophole in 1987 by declaring the President incapacitated, relying on a college of doctors specially selected for this purpose.

Since Ben Ali came to power, the president has been able to transfer his powers to the prime minister by decree, with the exception of the right to dissolve parliament. The government could then not be overthrown by a vote of no confidence until the end of the impeachment . In the event of permanent inability to officiate, be it due to death, resignation or unconditional prevention , it was initially the task of the Constitutional Council to meet immediately and to confirm the unconditional prevention with a simple majority. Thereafter, the chairman of the Chambre des députés was entrusted with the role of President for a period of 45 to 60 days. When the Chambre des députés was dissolved, the office passed to the chairman of the Chambre des conseillers . The interim president was sworn in in the same way as an elected president, but was not allowed to run in the following presidential election, even if he submitted his resignation beforehand. The interim president did not have the power to initiate referendums, dissolve the Chambre des députés, take special measures under Article 46 of the Constitution or dismiss the government. During the tenure of an interim president, the constitution could not be changed and no vote of no confidence in the government could be launched. After the overthrow of the previous ruler Ben Ali in January 2011, this provision was applied: the chairman of the Chamber of Deputies Fouad Mebazaa temporarily took over the vacant office until the constituent assembly appointed an interim president in December 2011.

Functions and powers of attorney

The constitutional amendments of 1988 and 1997 expanded the power of the president at the expense of that of the prime minister , such as control over administration and security forces, as well as the legislature. From then on, the President had the most extensive powers, while the legislature was limited to those rights granted by Article 35 of the Constitution.

From 2002 onwards, it was also no longer necessary for the legislature to ratify agreements that favored the President, with the exception of a few cases listed in Article 32. The constitutional amendments also weakened the lower house, Chambre des députés, compared to the upper house, Chambre des conseillers , the latter being elected only indirectly and a third of its members being elected by the president. As a result, almost all legislative initiatives came from the President, the executive power , who was the actual legislator of the country.

Executive powers

Article 38 of the Constitution, which was in force until 2011, gave the President executive powers and the role of head of state . Article 37 placed him alongside a government led by the Prime Minister. Article 50 gave him the right to appoint and dismiss the prime minister. He appointed members of the government on the proposal of the Prime Minister. The President had the right to dissolve the government, on his own initiative or at the proposal of the Prime Minister, or to dismiss one of its members, without Parliament having a say.

Article 49 grants him the right to define the basic lines of the state's policy and its foundations, about which he had to inform the House of Representatives. He chaired the Council of Ministers and, under Article 44, assumed the role of Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces . The President was able to dissolve the Chambre des députés in the event of two votes of no confidence during the same legislative period. If he assumed the vacant office of president as the newly elected president, he also had the right to dissolve the Chambre des députés (Article 63).

According to Article 41 of the Constitution, the President was the guarantor of independence, the inviolability of the territory and respect for the Constitution and the law. In accordance with Article 48, he concluded treaties on behalf of the Republic and ensured their implementation. He declared war and made peace, in each case with parliamentary approval. He supervised the proper work of the constitutional organs and ensured the continuity of the state.

Article 46 gave him the right to grant himself special powers in the event of imminent danger to the institutions of the republic, the security and independence of the country, or in the event of impairment of the proper functioning of the state organs . The same article gave him the right, in consultation with the Prime Minister and the Presidents of the two chambers of parliament, to take special measures until the circumstances that made the measure necessary are resolved . During the validity of the special powers, however, he was not allowed to dissolve the Chambre des députés , at the same time no motions of no confidence could be brought against the government .

Art. 53 gave the President the role of guardian over the application of the law and a general right of instruction , of which, however, he could assign a part to the Prime Minister. After all, he had the right to pardon those convicted .

Legislative Powers

The Tunisian constitution created a presidential form of government that pooled power in the executive. The President shared the right of initiative with Parliament. Under Article 26 of the Constitution, legislative proposals by the President took precedence over those of Parliament; In addition, the President could intervene in the legislation with legal decrees.

Laws were promulgated by the president. His office took over the up-to-date announcement in the Journal officiel de la République tunisienne , which had to happen within two weeks of receiving the legislative text from the chairman of one of the two chambers of parliament. However, the President had the right to return bills in whole or in part to Parliament for a second reading within this period. If it was passed by a two-thirds majority, it had to be announced and published within two weeks. Furthermore, the President could appeal to the Constitutional Council and, based on its judgment, send laws or parts of them back to Parliament for a new vote. The amended laws, passed with the majorities required in Article 28, had to be announced and published within the specified period.

Judicial Powers

The President appointed the judges and presided over the Supreme Judiciary under Article 66 of the Constitution. This fact established the dependence of the judiciary on the executive and the public prosecutor's office. The judges were terminable and could therefore be replaced by the president.

The President was also the only one who was allowed to call the Constitutional Council.

On July 14, 2001, Prosecutor Mokhtar Yahyaoui, a relative of Zouhair Yahyaoui , the founder of the Tunezine website , wrote an open letter to President Ben Ali, complaining about the lack of independence of the judiciary and calling on the President to hand over control by the executive branch break up. He deplored his disappointment at the poor conditions in Tunisia's judicial system, which prevents judicial authorities and judges from exercising their constitutional powers. Although this open letter received a lot of attention abroad, for Yahyaoui it meant dismissal and loss of income. He was finally removed from office on December 29 of the same year by a disciplinary committee that accused him of misconduct in performing his professional duties.

Right of nomination

Article 55 of the Constitution gave the President the right to appoint senior civil and military officials alongside the Prime Minister and members of the government. He did this at the suggestion of the government and was able to delegate this function to the Prime Minister for certain positions. The President accredited diplomatic representatives abroad and foreign diplomatic representatives in Tunisia in accordance with Article 45.

Right of initiative

Article 47, which was introduced with the constitutional amendment of 1997, gave the President the right to submit a legal text to the people for voting directly and without the approval of parliament if it was of national importance or concerned higher interests of the state . The only restriction was that the bill had to be in line with the Constitution, but it did not need the approval of the Constitutional Council. If the referendum approved the bill, the President had to proclaim it as law within 15 days of the publication of the vote.

The President was also allowed to put constitutional amendments approved by Parliament to the people for a vote (Rule 76).

President's office

The office of the president supported the head of state in the performance of his duties. It consisted of the following departments:

|

|

|

The following institutions were directly assigned to the President of Tunisia:

- the administrative mediator

- the Supreme Committee of Human and Fundamental Rights ( Comité supérieur des droits de l'homme et des libertés fondamentales )

- the Institute for Strategic Studies ( Institut tunisien des études stratégiques )

- the Supreme Committee for Administrative and Financial Control ( Haut comité du contrôle administratif et financier )

- the National Solidarity Fund

Bourguiba usually left the presidency of the Council of Ministers to the Prime Minister. He also refused to hire presidential advisers, preferring to work with ministers instead. By contrast, his successor, Ben Ali, held frequent small-scale councils of ministers and relied on his numerous consultative bodies.

immunity

With the constitutional amendment of 1997, the Tunisian head of state was freed from any responsibility. He was able to resolve conflicts with the government or parliament by dismissing the government or dissolving parliament (Article 63). From 2002 the president was also protected against any criminal prosecution. This also applied after the end of his term of office for all activities related to his administration.

The regulation did not absolutely rule out the possibility of the president being extradited to justice. It was up to the judge to decide whether his actions were private or public and whether they were related to his functions as president. The Supreme Court was only allowed to judge members of the government in cases of high treason (Article 68 of the Constitution), but not about the President , despite discussions in the founding assembly of the Republic from 1956–1959 . The question of abuse of office for personal gain was discussed in the constituent assembly, but the constitution did not contain any provision regarding the possible abuse of power by the president or the government.

As of September 2005, there was a law on the provision of pensions to presidents after resignation from their functions and their families in the event of death. President a. D. received an annuity that matched his income as president, including residence, staff and health care. After the president's death, this benefit was also available to his wife and children up to the age of 25.

Seat of the President

According to the constitution, the seat of the President is in Tunis or its vicinity. The used by the President of the Tunisian Republic Presidential Palace is located in the modern suburb of Carthage . In exceptional circumstances, the constitution allowed until 2011 to temporarily relocate the presidency to another location in Tunisia. A second presidential palace was built under Bourguiba in Monastir , which is now owned by the Tunisian state and not by the Bourguiba family.

Web links

- Official Website of the Presidency (Arabic)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Hatem Ben Aziza: De la monarchie constitutionnelle à la République , in: Réalités , No. 762, July 27, 2000.

- ↑ Fayçal Cherif: Les derniers jours de la monarchie , in: Réalités No. 1126, July 26, 2007.

- ^ A b Victor Silvera: Le régime constitutionnel de la Tunisie: la constitution du 1er juin 1959 , in: Revue française de science politique , 1960, Vol. 10, No. 2, p. 378.

- ↑ Les actualités françaises: Proclamation de la république en Tunisie , July 31, 1957.

- ↑ Marguerite Rollinde: Le mouvement marocain des droits de l'homme: entre consensus national et engagement citoyen , Paris (éd. Karthala) 2002, p. 108 ISBN 2-84586-209-1 .

- ^ Microsoft Encarta: Tunisie ( Memento of November 7, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) .

- ↑ A brief overview of the position of the president in the constitution up to 1990 by Wilfried Rather Gammarth: Die Verfassungsentwicklung Tunisiens (1955–1990). In: Yearbook of Public Law of the Present . NF Vol. 39, 1990, pp. 569-615, here pp. 595 f. : "The President of the Republic".

- ↑ Pascale Harter: Tunisia's Lackluster Election. In: BBC News , October 23, 2004; Ligue des droits de l'homme : La LDH solidaire avec Mouhieddine Cherbib et avec la FTCR face à l'intimidation politico-judiciaire de la dictature tunisienne. ( Memento of the original from November 20, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: LDH-France.org , September 22, 2008; Sue Pleming: Rice Pushes for Political Reforms in Tunisia. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Reuters , September 6, 2008.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Jurisite Tunisie: Articles 38 to 57 of the Constitution of Tunisia .

- ↑ Yuri Site Tunisie: Articles 66 and 67 of the Tunisian Electoral Code .

- ↑ a b Jurisite Tunisie: Articles 30 to 34 of Law n ° 2004-0052 of July 12, 2004 .

- ↑ a b c Les premières élections de la Tunisie indépendante. La domination totale du Néo-Destour , in: Réalités , No. 1058, April 6, 2006.

- ↑ Juristie Tunisie: Article 67-II of the Tunisian Electoral Code .

- ↑ Yuri Site Tunisie: Loi constitutionnelle n ° 2003-34 du 13 May 2003 portant dispositions dérogatoires au troisième alinéa de l'article 40 de la constitution .

- ^ Agence France-Presse: Tunisie: Ben Ali va assouplir les conditions de candidature à la présidence , March 21, 2008.

- ↑ Yuri Site Tunisie: Article 70 of the Electoral Code .

- ↑ a b c Jurisite Tunisie: Articles 26 to 37 of the Electoral Code .

- ↑ Tunis Afrique Presse: Décisions annoncées par le chef de l'État à l'occasion du 21e anniversaire du Changement , November 7, 2008 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Yuri Site Tunisie: Article 45 bis of the Electoral Code .

- ↑ Yuri Site Tunisie: Article 39 bis of the Electoral Code .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Samir Gharbi: Radiographie d'une élection. In: Jeune Afrique . dated November 2, 1999.

- ^ A b c Michel Camau, Vincent Geisser: Habib Bourguiba. La trace et l'heritage. Ed. Karthala, Paris 2004, ISBN 2-84586-506-6 , p. 241.

- ↑ Dominique Lagarde: Pluralisme à la tunisienne ( Memento of the original from April 22, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , L'Express , October 21, 1999.

- ↑ Le Grand Larousse Encyclopédique: Habib Bourguiba ( Memento of the original of April 5, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ^ Center d'études north africaines: Annuaire de l'Afrique du Nord , éd. Université du Michigan / Center national de la recherche scientifique, 1969, vol. 8, p. 389.

- ↑ After this election, Bourguiba was elected president for life on March 18, 1975 by the Chambre des députés . This was repealed after his disempowerment on July 25, 1988.

- ↑ The Microsoft Encarta ( Memento of 17 November 2007 at the Internet Archive ) 99.80% indicates.

- ↑ Anthony H. Cordesman: A Tragedy of Arms. Military and Security Developments in the Maghreb , Greenwood Publishing Group 2002, p. 250 ISBN 0-275-96936-3 .

- ↑ The Microsoft Encarta ( memento of November 7, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) gives a value of 99.44% and Le Canard enchaîné No. 4581 ( Carthage de ses artères , August 13, 2008, p. 8) a value of 99 , 40%.

- ↑ Présidence de la République tunisienne: Résultats de l'élection présidentielle de 2004 ( Memento of the original of November 17, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Élections 2009: Le président Ben Ali remporte l'élection présidentielle 2009 avec 89.62% ( Memento of the original of January 29, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Ridha Kéfi: Un scrutin en questions , Jeune Afrique , September 12, 2004.

- ^ Jean-Bernard Heumann, Mohamed Abdelhaq: Oppositions et élections en Tunisie. In: Maghreb-Machrek , No. 168, April / June 2000, p. 29.

- ↑ Yvan Schulz and Benito Perez: La non-élection tunisienne dénoncée à Genève ( Memento of the original of December 13, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , in: Le Courrier , October 15, 2004.

- ^ A b Chronique de Giulia Fois: Arrêt sur images, France 5 , October 24, 2004.

- ↑ Juristie Tunisie: Article 62-III of the Electoral Code .

- ^ Article 42 of the Constitution: Je jure par Dieu Tout-Puissant de sauvegarder l'indépendance nationale et l'intégrité du territoire, de respecter la constitution et la loi et de veiller scrupuleusement sur les intérêts de la nation.

- ↑ RafaA Ben Achour: La succession de Bourguiba. Codesria / Karthala Paris 2000, chapter: Les figures du politique en Afrique. Des pouvoirs hérités aux pouvoirs élus , p. 230.

- ↑ Présidence de la République tunisienne: Élections présidentielles en Tunisie ( Memento of the original of November 16, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ^ Tunisie Info: Déclaration du 7 November 1987 .

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Tuquoi, En Tunisie, un référendum constitutionnel ouvre la voie à la réélection de M. Ben Ali. in: Le Monde , May 16, 2002.

- ↑ a b c Hamadi Redissi: Qu'est-ce qu'une tyrannie élective? ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Jura Gentium , 2002.

- ↑ Sabine Lavorel: Les constitutions arabes et l'islam , Sainte-Foy (éd Presses de l'Université du Québec.) 2004. ISBN 2-7605-1333-5 .

- ↑ Florence Beaugé: L'opposant Sadri Khiari qualifie de "Putsch masqué" la reforme constitutionnelle en cours en Tunisie. in: Le Monde. May 23, 2002.

- ↑ a b RafaA Ben Achour: La succession de Bourguiba. Codesria / Karthala Paris 2000, chapter: Les figures du politique en Afrique. Des pouvoirs hérités aux pouvoirs élus , p. 229.

- ↑ a b RafaA Ben Achour: La succession de Bourguiba. Codesria / Karthala Paris 2000, chapter: Les figures du politique en Afrique. Des pouvoirs hérités aux pouvoirs élus , p. 227.

- ↑ RafaA Ben Achour: La succession de Bourguiba. Codesria / Karthala Paris 2000, chapter: Les figures du politique en Afrique. Des pouvoirs hérités aux pouvoirs élus , p. 228.

- ↑ RafaA Ben Achour: La succession de Bourguiba. Codesria / Karthala Paris 2000, chapter: Les figures du politique en Afrique. Des pouvoirs hérités aux pouvoirs élus , p. 230.

- ↑ a b c Jurisite Tunisie: Articles 18 to 36 of the Constitution of Tunisia .

- ↑ Yuri Site Tunisie: Article 66 of the Constitution of Tunisia .

- ↑ Yuri Site Tunisie: Article 72 of the Constitution of Tunisia .

- ^ A b c Amnesty International: Tunisie. Le cycle de l'injustice , June 10, 2003.

- ^ A b Transparency International , Djillali Hadjadj: Combattre la corruption. Enjeux et perspectives. Paris (éd.Karthala) 2002, p. 158 ISBN 2-84586-311-X .

- ↑ Cabinet présidentiel (Présidence de la République tunisienne) ( Memento of the original of September 21, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Journal officiel de la République tunisienne: Loi du 27 September 2005 relative aux avantages alloués aux présidents de la République dès la cessation de leurs fonctions (PDF; 476 kB) , n ° 78, September 30, 2005, p. 2557.

- ^ André Wilmots: De Bourguiba à Ben Ali: l'étonnant parcours économique de la Tunisie (1960-2000) , Paris (éd. L'Harmattan) 2003, p. 64f ISBN 2-7475-4840-6 .