R-7

The R-7 ( russ. Семёрка Semjorka "the Seven") was the world's first intercontinental ballistic missile . It was developed in the Soviet Union and is still in use today as the essentially unchanged Soyuz . The R-7 is one of the most reliable and the most widely used launcher in space travel . From 1953 it was built and used under the direction of Sergei Koroljow . In the absence of an official Russian name, the DIA code SS-6 or the NATO code name Sapwood (English for sapwood) was initially used in the West .

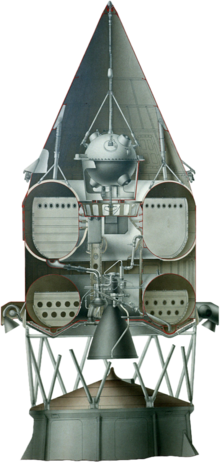

The first R-7 was 34 m high, 3 m in diameter, weighed 280 t, had two stages and was propelled by engines that used liquid oxygen and RP-1 , a type of kerosene, as fuel . As a ballistic missile , an R-7 could carry its payload up to 8800 km, with an accuracy of about 5 km.

development

The history of the R-7 can be traced back to 1950. That year the first studies for missiles with intercontinental range were carried out in the Soviet Union. These studies looked at cruise missiles , multi-stage ballistic missiles, and a combination of the two. These studies continued in 1951 and 1952. The idea of a rocket with bundled stages instead of a real multi-stage rocket was given preference and found to be technically possible. On February 2, 1953, OKB -1 (now RKK Energija ) in Kaliningrad , headed by Sergei Koroljow, received the order to develop a concrete proposal for a 170 t rocket with a range of 8,000 km. The resulting design was the R-6 (or T-1), which consisted of a central stage around which four R-5 missiles were bundled. The payload should be 3 t. In October 1953 the requirements for the design were changed. After the first successful Soviet test of a hydrogen bomb on August 12, 1953 ( RDS-6 ), the new missile was supposed to carry a thermonuclear warhead. The required payload was increased to 5.5 t. With the R-6 design, however, this was not possible, and a completely new program was started, the R-7. This should have a launch mass of 280 t with a range of 8000 km. The development of the R-7 with the GRAU index 8K71 was authorized on May 20, 1954. The basic design for the missile was completed in July 1954, and on November 20, 1954, the Council of Ministers of the USSR approved the final design.

With the development of the R-7, the OKB-1 was in direct competition with the development offices of Myasishchev and Lavochkin . They developed the intercontinental cruise missiles W-350 Burja and Object-40 Buran, which competed with the R-7 for the strategic carrier role. In addition to these competitors with a fundamentally different carrier concept, there was also competition within the Soviet missile industry. At the beginning of the development of the R-7, Korolev's OKB-1 was the only Soviet bureau for the design of large ballistic missiles. When developing the R-7, he relied on the relatively simple and high-energy fuel combination of kerosene and liquid oxygen. However, this had the disadvantage that the necessary cooling of the oxygen meant that it could not be stored in the rocket's tanks. This resulted in a long preparation time, as the rockets had to be refueled immediately before take-off. As a result, other rocket engineers, including the chief developer of rocket engines, Valentin Gluschko , urged the use of hypergolic fuels. With the usual hypergolic fuel combinations, both fuel and oxidizer are liquid under normal conditions and can therefore be stored permanently in the tanks of rockets. Korolev rejected the use of such a fuel combination, however, because on the one hand they are highly toxic and corrosive and on the other hand they provide less energy than kerosene and oxygen. Therefore, the Minister for the Defense Industry of the Soviet Union, Dmitri Ustinov , approved the establishment of a second design office for ballistic missiles under the direction of Mikhail Jangel (SKB-586) in June 1954. This should initially only develop a medium-range ballistic missile with hypergolic propellants (the R -12 ), but became the main competitor of the OKB-1 and the R-7 in the years to come.

The development program for the R-7 progressed relatively smoothly in 1955 and 1956. On March 20, the Council of Ministers of the USSR issued a decree allowing all measures for testing and further development of the missile. At that time, a new test site for the new rocket was already under construction. Earlier Soviet Union missile designs were launched from the 4th State Central Test Site Kapustin Yar in the south of the Russian SFSR . For the new missile, however, they were looking for a remote test site that was protected from espionage and radar surveillance. This began in 1955 in the steppe of the Kazakh SSR near the Tjuratam railway station . This 5th State Central Test Site was later named after Baikonur, some 400 km away . The Barmin development office was commissioned to develop the launch site for the R-7. The flight test program of the R-7 from this number 1 launch site began on May 15, 1957. The first three test flights on May 15, June 9 and June 12, 1957 failed for various reasons. The first successful flight, and thus the first successful ICBM flight in history, took place on August 21, 1957. The rocket covered a distance of 6400 km before the re-entry body broke over the Pacific Ocean. This test flight was officially announced on August 26th by the Soviet news agency TASS . The next two flights on October 4 and November 3, 1957 were also successful and at the same time were the world's first satellite launches ( Sputnik 1 and Sputnik 2 ). After these 6 flights, the R-7 was revised for the first time and equipped with a new warhead section to eliminate the problems that occurred on the fourth flight. Two other test series followed on 29 March 1958 to 10 July 1958, from 24 December 1958 to 27 November 1959. In the 16 test flights from the latter series came for the first time eight rockets from the factory for mass production in Kuibyshev for Commitment. The previous missiles were manufactured in a pilot factory at the development office. After the successful test program, the first unit with R-7 missiles was put into combat readiness in December 1959 on the specially constructed Angara launch site in the Arkhangelsk region (later the 53rd State Central Test Site in Plesetsk ). The first take-off of an R-7 from Plesetsk took place on December 15, 1959. Two days later, the Strategic Missile Forces of the Soviet Union were founded as a new branch of the Soviet military. They took control of all ICBMs and medium-range missiles in the country. On January 20, 1960, the R-7 officially entered service.

While the R-7 was still being tested, the Council of Ministers of the USSR approved the development of an improved model called the R-7A (GRAY index 8K74). It carried a lighter warhead, an improved navigation system, more powerful engines, and could hold more fuel. Nevertheless, the rocket had a takeoff weight 4 t less than the basic version. This increased their range from 8,000 km to 12,000 km. The test flight program of the R-7A took place from December 1959 to July 1960. The rocket entered service in September 1960 and replaced the basic R-7 version.

Use as an ICBM

After the first successful test flights of the R-7 in 1957, it became clear to the Soviet leadership that the ICBM concept was superior to intercontinental cruise missiles and long-range bombers. Therefore, the competing Buran program of Myasishchev was canceled in 1957, the Burya program of Lavochkin was continued until 1958 and discontinued after a few successful test flights. The development of the strategic bomber fleet also stagnated until the end of the 1970s. Compared to cruise missiles and bombers, ICBMs like the R-7 promised to be able to penetrate the defense of any enemy and to reach their targets in the shortest possible time.

During the progressive development of the R-7 it also became clear that the technical concept of the R-7 had serious shortcomings for use as a weapon. The original plans of the Soviet leadership provided for the R-7 to be stationed on secret bases, from where they should carry out a counter-attack in the event of an American attack on the Soviet Union. But it soon became clear that the location of the R-7 was not to be kept secret from the USA. The huge rocket with its 280 t launch mass needed large above-ground launch facilities, which could easily be discovered by spy flights (and later satellite reconnaissance). Due to the size and complexity of the necessary systems, these could not be hardened against near nuclear weapon explosions. The complexity and fuel combination used by the R-7 resulted in a take-off preparation time of around 24 hours. Even after it was installed on the launch pad, it took about two hours for the rocket to be ready for launch. This meant that the R-7 missiles could not respond to a surprise attack on the Soviet Union.

The most serious problem for the R-7 as a weapon, however, was the cost of the launch systems. Even before the first flight of the R-7 in 1957, construction of the first missile base near the town of Plesetsk in the Arkhangelsk region began. Due to the limited range of the basic variant of the R-7, the launch facilities had to be located far in the north of Russia so that the missiles could reach the most important targets in the USA. However, this not only reduced the advance warning time in the event of an attack on the launch facilities, but also made construction considerably more difficult, as the planned bases were all located in the permafrost belt. The original plan provided for the construction of five launch bases, each with twelve launch ramps, for the R-7. However, the construction of the first of these bases turned out to be a highly complex project with steadily increasing costs and delays due to the difficult underground and climatic conditions. The cost of a launch pad was finally estimated at around 500 million rubles, about 5% of the then Soviet defense budget. Due to the escalating costs, it was therefore decided in 1958 to complete only the 4 launch ramps currently under construction in Plesezk for the R-7 and to cancel the other stationing plans. The resulting low number of available R-7 missiles in combination with the missile's low accuracy (the maximum error was around 10 km) meant that the missile was useless for a preventive or first strike against the USA.

In the same year that the R-7 program was slashed, final development of the OKB-586's R-16 ICBM was approved, which aimed to overcome many of the R-7's disadvantages, primarily through the use of storable fuels. However, Korolev convinced the Soviet government that one could develop a powerful ICBM with cryogenic fuels without the disadvantages of the R-7. On March 13, the development of the R-9 was approved, so that the R-7 now also had competition within OKB-1.

The first ramp for the R-7 was completed in February 1959 and the first missile unit went into service on February 9, 1959 at the new location. However, the first missile was not put into combat readiness until December, along with the first test flight of the R-7 from Plesetsk and the establishment of the Soviet Union's Strategic Missile Forces. Series production of the rocket had started in the same year and 30 pieces were ordered, followed by another order for 70 rockets in 1960. By 1966, the current five-year plan of the USSR provided for the production of 210 rockets, including launchers for the Space program.

With the commissioning of the R-7A at the end of 1960 it became possible to attack targets in the USA from the now two ramps in Baikonur. In addition to the space flight and test launch role, the ramps in Baikonur were also given a secondary task as a launch site for operational R-7A in the event of a crisis. This happened z. B. during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, when an R-7A was being prepared for take-off in Baikonur. However, the missile was not installed on the ramp before the crisis ended. From 1963 and 1964 the ramps in Plesezk were mainly used for satellite launches and the importance of the R-7 as a weapon faded more and more into the background. In 1968 the last R-7A ICBMs were finally decommissioned. Many analysts do not classify the R-7 as one of the first generation ICBMs, as it was only deployed in very limited numbers and had many restrictions for its use. For comparison, the Atlas missile developed at the same time in the USA with the same fuel combination was able to transport a similarly powerful warhead as the R-7 over a comparable distance with less than half the launch mass, a launch preparation time of only 15 to 20 minutes, a much longer one Accuracy and the possibility of stationing them in bunkers or silos. However, none of the inadequacies of the R-7 played a role in its use as a launcher, and so it became the basis of the most successful family of missiles to date.

1st generation ICBM in comparison

| Country | USSR | United States | |||

| rocket | R-7 / R-7A | R-16 / R-16U | R-9A | SM-65 Atlas (-D / -E / -F) | SM-68 Titan I |

| developer | OKB-1 ( Korolev ) | OKB-586 ( Jangel ) | OKB-1 (Korolev) | Convair | Glenn L. Martin Company |

| Start of development | 1954/1958 | 1956/1960 | 1959 | 1954 | 1958 |

| first operational readiness | 1959/1960 | 1961/1963 | 1964/1964 | 1959/1961/1962 | 1962 |

| Retirement until | 1961/1968 | 1976/1976 | 1976 | 1964/1965/1965 | 1965 |

| Range (km) | 8,000 / 9,500-12,000 | 11,000-13,000 | 12,500 | n / A | 10,000 |

| control | radio-inertial | inertial | radio-inertial | radio-inertial / inertial | radio-inertial / inertial |

| CEP (km) | 10 (maximum error) | 4.3 | 8-10 | n / A | <1.8 |

| Takeoff mass (t) | 280/276 | 141/147 | 80 | 118/122/122 | 103 |

| stages | 1.5 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 | 2 |

| Fuel combination | Kerosene / LOX | UDMH / nitric acid | Kerosene / LOX | Kerosene / LOX | Kerosene / LOX |

| Stationing type | launch pad | Launch ramp / silo | Launch ramp / silo | Launch ramp / bunker / silo | silo |

| Max. Overpressure ( psi ; protection of the starting system in the event of an explosion) | k. A. | k. A. / 28 | k. A. / 28 | k. A. / 25/100 | 100 |

| reaction time | about 24 h | Ten minutes - several hours | 20 min / 8-10 min | 15-20 min | 15-20 min |

| Guarantee period (when on high alert) | n / a | 30 days (fueled) | 1 year | k. A. | 5 years |

| Explosive strength of the warhead ( MT ) | 3-5 | 3-6 | 5 | 1.44 / 3.75 / 3.75 | 3.75 |

| Max. stationed number | 6th | 186 | 23 | 30/27/72 | 54 |

technology

The core problem in Soviet missile development was initially to move large nuclear warheads intercontinentally in a short time . That is why there was an intensive search for high-performance concepts in which development time for rocket motors could be saved. The bundling of similar drives with simultaneous ignition of all stages on the ground turned out to be the most promising. Before the rocket was lifted off, it was possible to check whether all the engines were working properly, and only then was the rocket released from the launch table.

However, an ICBM was only feasible with a two-stage concept. This was achieved through a longer central stage for the middle engine, which after the separation of the four outer stages ( booster ) further accelerated the payload. This also avoided the problem of having to ignite the second stage of the rocket in flight, which was not technologically solved at the time.

The central stage (stage 2) of the R-7 used a RD-108 - rocket engine with four combustion chambers , the RP-1 and liquid oxygen (LOX) burned. Almost the same engines were used for the boosters with the RD-107 . With the relatively symmetrical thrust characteristics, simple gyro systems with time switch elements were suitable as controls. The basic direction was given by a rotating starting table. Only the launch of larger satellites on defined orbits required upper levels.

Since there was no experience in the operation and launch of larger rockets in the 1950s and there was fear of damage to the fairly wide R-7 from gusts of wind, the engineers designed a sophisticated launch table for the R-7, which was also used by its successors: The rocket did not stand on a platform, but was hung on its side boosters so that the launch arms closed around it like the leaves of a flower; the principle was therefore also called “tulip”. During takeoff, the arms opened exactly at the moment when the thrust of the engines balanced the weight of the rocket and only then could the rocket leave the launch table. This also ensured that liftoff only took place if all boosters were delivering evenly. The concept seems complicated compared to the launch tables of later rockets, but in the almost 50 years of operation of the R-7 and its successors there have been no incidents at the launch system.

Use as a launcher

Although a failure as a weapon system, the R-7 was further developed into a family of launch vehicles for space travel , which have been used intensively to launch a wide variety of payloads, including manned spacecraft and interplanetary space probes, to this day. The first satellite was launched with an ordinary R-7, which was named Sputnik . Only the section of the missile, which contained the warhead and the flight control, was dismantled and a smaller conical adapter was used in its place, which only contained the systems necessary for a flight. Later, modifications to the engines resulted in the Sputnik-3 rocket, which after an initial false start on May 15, 1958, carried the Sputnik-3 satellite into space. The other modifications of the R-7 concerned the addition of new stages, new engines, etc. Over the years, several variants of the launchers were created, which have been constantly modified and are now among the world's most robust and reliable missiles:

- Vostok : an R-7 with an additional third stage. First launched in 1958, no longer in use today.

- Luna : another name for an early version of the Vostok. Started the first Lunik probes, no longer in use today.

- Molnija : an R-7 with a new and larger third stage and a fourth stage for soaring satellites and interplanetary spacecraft. First start in 1960, in use until 2010.

- Vozhod : a Molnija without the fourth stage for payloads in low orbits. First launched in 1963, no longer in use today.

- Poljot : a two-tier version of the vozhod. First launched in 1963, no longer in use today.

- Soyuz : a slightly modified Vozhod. First launched in 1966, still in use today.

- Soyuz Fregat : a Soyuz with an additional fourth stage ( Fregat ) for soaring satellites and interplanetary space probes. First start in 2000, still in use today.

- Soyuz 2 : a Soyuz with digital flight controls and a new third stage. First start 2004.

- Jamal / Aurora / Onega / Soyuz 3 : planned or proposed further developments of the Soyuz, which have a central stage with a larger diameter, a new third stage, other engines and a take-off mass that is around a quarter higher than the Soyuz. Currently in the concept study phase.

Launch rocket data based on the R-7

As of December 31, 2019

| carrier |

GRAY index |

stages | Height (m) |

Starting mass (t) |

Starts | of which false starts |

according to starting place | commitment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bai | Ple | from | to | |||||||||

| ICBM R-7 | 8K71 | 2 | 25th | 9 | 25th | May 15, 1957 | 1960 | |||||

| sputnik | 8K71PS | 29.167 | 267 | 2 | 0 | 2 | Oct. 4, 1957 | 1957 | ||||

| Sputnik-3 | 8A91 | 31 | 269 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Feb 3, 1958 | 1958 | ||||

| Vostok (Luna) | 8K72 | 3 | 33,500 | 279 | 13 | 7th | 13 | 23 Sep 1958 | 1960 | |||

| ICBM R-7A | 8K74 | 2 | 26th | 2 | 23 | 3 | 23 Dec 1959 | 1967 | ||||

| Molnija | 8K78 | 4th | 43,440 | 305 | 40 | 20th | 40 | - | Oct 10, 1960 | 1967 | ||

| Vostok-K | 8K72K | 3 | 38.246 | 287 | 13 | 2 | 13 | - | Dec 22, 1960 | 1964 | ||

| Vostok-2 | 8A92 | 44 | 7th | 38 | 6th | June 1, 1962 | 1967 | |||||

| Poljot | 11A59 | 2 | 30th | 277 | 2 | 0 | 2 | - | Nov 1, 1963 | 1964 | ||

| Vozhod | 11A57 | 3 | 44.628 | 298 | 299 | 14th | 133 | 166 | Nov 16, 1963 | 1976 | ||

| Molnija-М | 8K78M | 4th | 43,440 | 305 | 280 | 14th | 50 | 230 | 19 Feb 1964 | 2010 | ||

| Vostok-2М | 8A92M | 3 | 38.246 | 287 | 94 | 2 | 14th | 80 | Aug 28, 1964 | 1991 | ||

| Vostok-2A | 11A510 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | - | Dec. 27, 1965 | 1966 | ||||

| Soyuz | 11A511 | 3 | 50.670 | 308 | 31 | 2 | 31 | - | Nov 28, 1966 | 1976 | ||

| Soyuz-L | 11A511L | 44 | 305 | 3 | 0 | 3 | - | Nov 24, 1970 | 1971 | |||

| Soyuz-М | 11A511M | 50.670 | 310 | 8th | 0 | - | 8th | Dec. 27, 1971 | 1976 | |||

| Soyuz-U | 11A511U | 51,100 | 313 | 776 | 20th | 340 | 436 | May 18, 1973 | 2017 | |||

| Soyuz-U2 | 11A511U2 | 72 | 0 | 72 | - | 23 Dec 1982 | 1995 | |||||

| Soyuz-U / Ikar | 11A511U | 4th | 47.285 | 308 | 6th | 0 | 6th | - | Feb 9, 1999 | 1999 | ||

| Soyuz-U / Fregat | 11A511U | 46.645 | 4th | 0 | 4th | - | Feb 8, 2000 | 2000 | ||||

| Soyuz-FG | 11A511FG | 3 | 49.476 | 305 | 59 | 1 | 59 | - | May 20, 2001 | 2019 | ||

| Soyuz-FG / Fregat | 4th | 10 | 0 | 10 | - | June 2, 2003 | 2012 | |||||

| ▲ retired in action ▼ | ||||||||||||

| carrier |

GRAY index |

stages | Height (m) |

Starting mass (t) |

Starts | of which false starts |

according to starting place | commitment | ||||

| Bai | Ple | What | CSG | since | to | |||||||

| Soyuz-2.1a | 14A14 372RN16 |

3 | 19th | 1 | 15th | 4th | 0 | Nov 8, 2004 | ||||

| Soyuz-2.1a / Fregat | 4th | 50.670 | 311 | 16 | 2 | 7th | 7th | 2 | Oct 19, 2006 | |||

| Soyuz-2.1b / Fregat | 14A15 372RN17 |

24 | 3 | 4th | 18th | 2 | Dec 27, 2006 | |||||

| Soyuz-2.1b | 3 | 9 | 0 | 3 | 6th | 0 | July 26, 2008 | |||||

| Soyuz ST-B / Fregat | 372RN21 | 4th | 46.2 | 315 | 16 | 1 | 16 | Oct 21, 2011 |

approx. 2025 |

|||

| Soyuz ST-A / Fregat | 7th | 0 | 7th | Dec 17, 2011 | ||||||||

| Soyuz-2.1w / Volga | 131KS | 3 | 44 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | Dec 28, 2013 | |||

| Soyuz-2.1a / Volga | 4th | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Apr 28, 2016 | |||||

| Soyuz-2.1w | 131KS | 2 | 44 | 156 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 29 Mar 2018 | ||

| Total: | 1909 | 108 | 911 | 970 | 5 | 23 | ||||||

False starts = the payload was not launched into the intended orbit.

italic = planned

Source for all launch statistics: Gunter's Space Page, with correction of the missile type for the Progress MS-07 mission z. B. via Russian Space Web

See also

Web links

- R-7 rocket from SP Korolev Rocket and Space Corporation Energia, formerly OKB-1

- R-7 and its successor by Bernd Leitenberger

- Article about the role of the R-7 in the Cold War arms race by Matthias Uhl on Katapult, July 13, 2015

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k P. Podvig (Ed.): Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces. MIT Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-262-16202-9 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m S. J. Zaloga : The Kremlin's Nuclear Sword - The Rise and Fall of Russia's Strategic Nuclear Forces, 1945-2000. Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001, ISBN 1-58834-007-4 .

- ^ Donald E. Weizenbach: "Observation Ballon and Reconnaissance Satellites", p. 25. Central Intelligence Agency , December 31, 1960, archived from the original on August 2, 2012 ; Retrieved April 20, 2010 .

- ↑ a b c d e f Norris, R., Kristensen, H., 2009. Nuclear US and Soviet / Russian Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles, 1959–2008. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

- ↑ a b c David Stumpf Titan II - A History of a Cold War Missile Program . University of Arkansas Press, 2000. ISBN 1-55728-601-9

- ↑ a b SM-65 Atlas on globalsecurity.org

- ↑ Launch vehicles - USSR / Russia on space.skyrocket.de

- ↑ Russian space program in 2017 on Russian Space Web, accessed October 29, 2019.