Leafhopper

| Leafhopper | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The alpine foam cicada ( Aphrophora major ) is the largest Central European foam cicada with a length of up to 12.5 millimeters. |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Aphrophoridae | ||||||||||||

| Evans , 1946 |

Foam leaf hoppers (Aphrophoridae), engl. "Spittlebugs" are a family of the Cercopoidea within the suborder of the round head cicadas (Cicadomorpha, Clypeorrhyncha). They are mostly inconspicuously straw-colored, brownish or black in color - in contrast to the blood-hoppers (Cercopidae), which are markedly black and red. Another characteristic feature of these insects is that the larvae live in above-ground, self-produced, foam covers called cuckoo saliva; hence the family name. The foam cicadas include around 850 described species worldwide.

Outer shape

In contrast to the representatives of their sister group , the blood-hoppers (Cercopidae), foam cicadas are mostly inconspicuous, straw-colored, brownish or black in color. The body shape is usually elongated or broad-elongated oval. The hairy or hairless elytra are leathery and covered with pits. Foam cicadas are often confused with beetles (Coleoptera), but are easily recognizable as cicadas by their roof-like wing posture. The membranous hind wings lie under the forewings.

The feet ( tarsi ) of the foam cicadas are tripartite. The rails of the rear pair of legs ( tibia ) are round and relatively short. The rails of the hind legs have one or two strong thorns (non-European species sometimes more) and a wreath of thorns ( meron ) at the base. In contrast to the sluggish larvae, adult leafhoppers jump well with their strong legs. The thorns on the hind legs provide support on the ground when jumping.

When viewed from above, the head of the foam cicadas - in contrast to the blood cicada - is usually as wide as the pronotum and has two point eyes ( ocelles ), a pair of compound eyes and a pair of short, bristle-shaped antennae . The forehead plate ( clypeus ) (head part between the ocelles, see illustration) is more or less vaulted, depending on the species, when viewed from the front and the side.

Like all leafhoppers, leafhoppers also have a proboscis for feeding. The lower lip ( labium ) of the animals is designed as a slide for the spikes made up of the mandibles and maxillae . Inside the laciniae (part of the maxilla) there is a channel through which suction can take place, as well as a saliva channel through which saliva is conducted into the feeding site. The cibarium , part of Mundvorraums is, as with all Schnabelkerfen transformed into a suction pump.

Internal structure and physiology

The internal anatomy and physiology of the leafhoppers largely correspond to those of the insects. In adaptation to the special diet, like all round-headed leafhoppers, foam leafhoppers have a special construction of the digestive tract in order to release excess water or carbohydrates . The very water-rich plant sap of the conduction pathways ( xylem ) is, in contrast to the sugar-rich phloem sap, significantly poorer in nutrients, which is why leafhoppers that only feed on it have to ingest a lot of them. There is a filter chamber in the intestine of the sap suckers, which creates a transition region between the fore and midgut and the hindgut. It allows the excess water to be drained directly into the rectum and the nutritional juice is thickened before it enters the midgut. Furthermore, the centers of the rope ladder nerve systems typical of insects are only present in the round-headed cicadas in the head and chest; the abdomen is supplied by the nerve center of the chest.

Distribution and habitats

Foam leaf hoppers are common in all zoogeographic regions with the exception of the Arctic and Antarctic . They are very species-rich , especially in the tropics . New species are currently being discovered and their phylogenetic position investigated, especially in the Neotropic .

Foam leaf hoppers colonize almost all biotopes . They are particularly widespread in grass- rich ecosystems such as dry grasslands and steppes through to wet and wet meadows and in swamps and moors . They also live in forests and on the edges of forests , from the boreal coniferous forests to the deciduous forests of the temperate latitudes to the rainforests of the tropics. Foam leaf hoppers are adapted to the abiotic and biotic environmental factors of their habitats such as moisture, soil or vegetation structures. A number of species are hydrophilic , which means that they prefer moist to wet habitats and therefore live on the banks of bodies of water or in wet meadows (e.g. the foam grasshopper , Neophileanus lineatus ). Other species, however, are xerophilic . They live in dry grasslands such as the steppe foam cicada ( Neophilaenus infumatus ). Several species prefer to colonize sandy soils or bog soils made of peat . So you are psammophilic or tyrphophilic . Still other species require a certain structure of the vegetation. Some species of the genus Aphrophora, for example the alder leafhopper ( Aphrophora alni ), are so-called "Stratenchangers" (sing. Stratum; pl. Straten = layer (s)). While the larvae develop in the herb layer, the adult animals switch to the shrub and tree layers . Many of the species mentioned are stenotopic , which means that they only occur in a few, relatively similar habitats. Other species, however, are eurytopic and occur in many different biotopes, such as the meadow-foam cicada ( Philaenus spumarius ).

Way of life

Common to all foam leaf hoppers is the sucking diet and the mostly poorly developed host plant specificity, which means that many species are not very particular about their nutrient plants. The larvae live in foam nests above ground, mostly in the herb layer on sweet and sour grasses (e.g. Neophilaenus) and herbaceous plants (e.g. Philaenus), but sometimes also on woody plants (e.g. Aphrophora).

nutrition

As with all leafhoppers, foam leafhoppers are fed by piercing and sucking out certain parts of the plant, as it were through a straw. As xylem suckers , they feed on the ascending juice of the ducts. Foam leaf hoppers are mostly polyphagous to oligophagous , so they are not very particular about their food. They use several plant genera or families, which sets them apart from most other species of cicada. Nutrient plants are mainly grasses , rushes and dicotyledonous plants ; the genus Aphrophora also sucks on woody plants.

Reproduction and development

Like all male cicadas and sometimes females, the males of the foam cicadas are able to produce rhythmic chants. These are generated by special drum organs ( tymbal organs ), which are located on the sides of the 1st abdominal segment. By pulling a strong sing muscle, the membranes of the drum organs are set in vibration. The noise is generated by indenting (muscle pull) and jumping back (inherent elasticity).

- pairing

Mating is initiated by the male by anchoring his genital fittings to that of the female. It sits diagonally next to the female during the entire copulation and holds on to the side. This creates a V-position typical for foam cicadas and other representatives of the Cicadomorpha.

- Development of the larvae

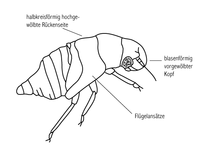

Foam leaf hoppers are hemimetabolic . They undergo an incomplete transformation from the egg via the larva directly (without the pupal stage) to the full insect ( imago ). The development of the larvae takes place over five stages, whereby with increasing age the facilities for the organs of the adult animal (wings, genital fittings) form and enlarge. The various stages merge into one another via molting. The back of the larvae is highly arched in a semicircular cross-section, the belly is concave. The head is strongly bulged in front of the antennae and eyes and overall round. The larvae live wrapped in a foam nest on the stems and leaves of herbaceous plants or woody plants. They have a respiratory cavity on their abdomen that has evolved from the folds of the abdominal rings. The respiratory orifices (stigmata), the points where the trachea meet on the surface of the body, are located in the respiratory cavity . The trachea form a system of breathing tubes that runs through the entire body of an insect and is the functional equivalent of our lungs . The foam is generated by rhythmically pumping in air bubbles from the respiratory cavity into a protein-containing liquid, which the larvae secrete from the anus. This process continues until the imago leaves the excrement . The consistency of the foam is maintained with mucilage from glycosaminoglycans (formerly mucopolysaccharides ) and proteins , which are excreted from special excretory organs in the intestine ( Malpighian vessels ). The foam also protects the larvae sitting in it from enemies, but primarily receives the moisture and temperature necessary for further development. Studies have shown that the foam of the meadow leaf hoppers ( Philaenus spumarius ) and the brown willow leaf hoppers ( Aphrophora salicina ) consists of 99.30% and 99.75% water, respectively.

Phylogeny and systematics of the Aphrophoridae

According to current opinion, the Cercopoidea are next to the Membracoidea and the Cicadoidea a superfamily of the round-headed leafhopper (Cicadomorpha). It comprises the families Cercopidae , Aphrophoridae (including Epiphygidae), Clastopteridae and Machaerotidae (see figure on the right). A comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of the superfamily of the cercopoidea based on the determination of ribosomal 18S-r DNA , 28S-rDNA and histones 3 confirms the monophyly of the superfamily. Furthermore, the Cercopidae family has been identified as a monophyletic group, while its sister group Aphrophoridae is likely a Paraphyllum . Another neotropically widespread family, the Epiphygidae , was recently split off as a sister group of the Aphrophoridae, whereby the larvae of this family apparently do not produce any foam, but otherwise have all the characteristics of the Cercopoidea. It is certain that the larvae of the representatives of the families Cercopidae, Aphrophoridae and Clastopteridae live in foam nests. An exception are the tropical Machaerotidae, whose larvae live in water-filled, self-made calcareous tubes.

Species selection

In Central Europe, the genera Lepyronia and Philaenus contain species with a broad oval body shape. The latter is a standard example of intraspecific color and drawing polymorphism . All shapes have their own names. Neophilaenus is the most species-rich genus of the Aphrophoridae. The species of this genus are significantly slimmer than the species of the aforementioned genera. The genus Aphrophora includes comparatively large species with a body length of up to 12.5 millimeters.

Species in Europe

In Europe there are 29 species in 7 genera of the Aphrophoridae, of which 15 species occur in 4 genera in Central Europe and 13 species in 4 genera in Germany. German species names exist for all species known from Central Europe.

Genus Aphrophora

- Alder- foam cicada , Aphrophora alni ( Fallén , 1805), Central Europe including Germany

- Pine foam cicada , Aphrophora corticea ( Germar , 1821), Central Europe including Germany

- Alpine foam cicada , Aphrophora major Uhler , 1896, Central Europe including Germany

- Colorful willow- foam cicada , Aphrophora pectoralis Matsumura , 1903, Central Europe including Germany

- Brown willow leaf hoppers , Aphrophora salicina ( Goeze , 1778), Central Europe including Germany

- Siberian foam cicada , Aphrophora similis Lethierry , 1888, northeastern Poland to eastern Palearctic

Genus Lepyronia

- Wanstschaumzikade , Lepyronia coleoptrata ( Linnaeus , 1758), Central Europe incl. Germany

Genus Mesoptyelus

- Mesoptyelus petrovi ( Grigoriev , 1910)

Genus Neophilaenus

- Zwenkenschaumzicade , Neophilaenus albipennis ( Fabricius , 1798), Central Europe including Germany

- Neophilaenus angustipennis ( Horváth , 1909)

- Foam leaf hoppers , Neophilaenus campestris ( Fallén , 1805), Central Europe including Germany

- Forest foam cicada , Neophilaenus exclamationis ( Thunberg , 1784), Central Europe including Germany

- Steppenschaumzikade , Neophilaenus infumatus ( main including, 1917), Central Europe. Germany

- Carniolan foam cicada , Neophilaenus limpidus ( Wagner , 1935), Slovenia, Northern Italy

- Foam leaf hoppers , Neophilaenus lineatus ( Linnaeus , 1758), Central Europe including Germany

- Neophilaenus longiceps ( Puton , 1895)

- Dwarf cicada , Neophilaenus minor ( Kirschbaum , 1868), Central Europe including Germany

- Pointed-head cicada , Neophilaenus modestus ( Haupt , 1922), Central Europe

- Neophilaenus pallidus ( Haupt , 1917)

Genus Paraphilaenus

- Paraphilaenus notatus ( Mulsant & Rey , 1855)

Genus Peuceptyelus

- Peuceptyelus coriaceus ( Fallén , 1826)

Genus Philaenus

- Philaenus italosignus Drosopoulos & Remane , 2000

- Philaenus lukasi Drosopoulos & Ashes , 1991

- Philaenus maghresignus Drosopoulos & Remane , 2000

- Philaenus signatus Melichar , 1896

- Meadow foam cicada , Philaenus spumarius ( Linnaeus , 1758), Central Europe including Germany

- Philaenus tarifa Remane & Drosopoulos , 2001

- Philaenus tesselatus Melichar , 1899

Species and genera outside Europe (selection)

- Amarusa australis ( Jacobi , 1921)

- Anyllis leiala Kirkaldy , 1906

- Anyllis spinostylus Liang , 2005

- Aphrophora cribrata ( Walker , 1851)

- Basilioterpa fasciata ( Evans , 1966)

- Basilioterpa pallida ( Evans , 1966)

- Bathyllus albicinctus ( Erichson , 1842)

- Carystoterpa fusiformis Hamilton & Morales , 1992

- Cephisus siccifolius ( Walker , 1851)

- Interocrea nigrofasciata ( Kirkaldy , 1906)

- Interocrea regalis ( Lallemand , 1927)

- Lepyronia quadrangularis ( Say , 1825)

- Liorhina loxosema ( Hacker , 1926)

- Novaphrophara tasmaniae Lallemand , 1940

- Philagra concolor hackers , 1826

- Philagra fulvida Hacker , 1826

- Philagra parva ( Donovan , 1805)

- Philagra recurva Jacobi , 1928

Economical meaning

The Central European leafhoppers are largely economically insignificant. There are only isolated indications of harmful effects. There are some species in which a mass development with a corresponding foam development is known. Often it is the brown and colored willow leafhopper ( Aphrophora salicina , A. pectoralis ) whose imagines and larvae suckle on shoots and branches of willow trees in spring . The very rough punctures cause the plant tissue to form suction scars ( wound callus ). If there are masses of cicadas or their larvae, characteristic bulge-like callus rings are created in this way, as the punctures lie in rows across the longitudinal direction of the shoots. This increases the susceptibility of the branches to breakage. The females lay eggs in the bark and wood of willow trees in summer. With correspondingly dense oviposition, shoots can wilt, which can lead to the multiplication of bark pathogenic fungi .

In West and Central Africa , Poophilus costalis ( Walker , 1851) causes significant agricultural damage to black millet ( Sorghum bicolor ), maize ( Zea mays ) and sugar cane ( Saccharum officinarum ). The foam cicada sucks on all parts of the plant including the panicles . This is how it transmits Colletotrichum camelliae , the pathogen causing yellow spot disease . This can cause young leaves and whole plants to die.

particularities

In addition to the characteristic property of the foam nests in which the larvae of the foam cicadas develop, there are a number of other special features in this group of animals. Sometimes the foam flakes produced by the larvae of the colorful and brown willow cicada ( Aphrophora pectoralis, A. salicina ) appear so large and numerous in willows ( Salix ) that liquid drips out of them and, as it were, rains out of the tree. Commonly one speaks of "weeping willows".

Foam cicadas are the world champions in high jump. The researcher Malcolm Burrows discovered this on high-speed photos. In relation to its own body length, no living being can jump as high as the meadow foam cicada ( Philaenus spumarius ). The insect is about half a centimeter long and reaches a height of 70 centimeters from a standing position. We humans would have to be able to jump about 200 meters high in relation to our body size to catch up with the cicadas. Like every insect, the meadow-foam cicada has three pairs of legs; Only the rearmost pair provides jump energy. The animal can build tension in these legs like in a catapult and then discharge it.

Sources and further information

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gernot Kunz, Cicadas - the insects of the 21st century? (Hemiptera, Auchenorrhyncha). Entomologica Austriaca, Volume 18, 2011, pp. 105-123.

- ↑ Wilfried Westheide, Reinhard Rieger (ed.): Special Zoology, Part 1: Protozoa and invertebrates. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart, Jena, New York 1996, pp. 650–651.

- ^ A b R. Remane, E. Wachmann : Cicadas - get to know, observe - Naturbuch Verlag, Augsburg 1993, ISBN 3-89440-044-7 .

- ↑ W. Westheide, R. Rieger (Ed.): Special Zoology, Part 1: Protozoa and invertebrates. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart, Jena, New York, 1996, pp. 651-652.

- ^ A b J. R. Cryan: Molecular phylogeny of Cicadomorpha (Insecta: Hemiptera: Cicadoidea, Cercopoidea, and Membracoidea): adding evidence to controversy. Systematic Entomology 30 (4), Oct 2005, pp. 563-574.

- ↑ Hubert Ziegler, Irmgard Ziegler: About the composition of the cicada foam. Journal of Comparative Physiology , Vol. 40, pp. 549-555, 1958.

- ^ CH Dietrich: Evolution of Cicadomorpha (Insecta, Hemiptera). In: Cicadas, leafhoppers, planthoppers and cicadas (Insekta, Hemiptera, Auchenorrhyncha). 2002, In: Denisia 4, pp. 155-169, 2002, ISBN 3-85474-077-8 .

- ↑ Aphrophoridae in Fauna Europaea , as of March 2, 2015.

- ^ WE Holzinger: Provisional directory of the cicadas of Central Europe (Insecta: Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha et Cicadomorpha); Preliminary checklist of the Auchenorrhyncha (leafhoppers, planthoppers, froghoppers, treehoppers, cicadas) of Central Europe , Stand 2003 ( [1] ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this note .; PDF; 122 kB), accessed on May 8, 2007

- ↑ a b Herbert Nickel and Reinhard Remane: List of species of cicadas in Germany, with information on nutrient plants, food breadth, life cycle, area and endangerment (Hemiptera, Fulgoromorpha et Cicadomorpha). Contributions to the cicada, 5, pp. 27–64, 2002 full text (PDF, German; 234 kB)

- ^ WE Holzinger, I. Kammerlander, H. Nickel: The Auchenorrhyncha of Central Europe - Die Zikaden Mitteleuropas. Volume 1: Fulgoromorpha, Cicadomorpha excl. Cicadellidae. - Brill, Leiden 2003, ISBN 90-04-12895-6

- ↑ according to NCBI Taxonomy Browser [2] , accessed on August 29, 2006

- ↑ after MJ Fletcher: Identification Key and Checklists for the Froghoppers and Spittlebugs (Hemiptera: Cercopoidea) of Australia and New Zealand. [3] , accessed August 29, 2006

- ^ O. Ajayi & F A. Oboite: Importance of spittle bugs, Locris rubens (Erichson) and Poophilus costalis (Walker) on sorghum in West and Central Africa, with emphasis on Nigeria Annals of Applied Biology, Volume 136 Page 9 - February 2000 doi : 10.1111 / j.1744-7348.2000.tb00002.x .

- ↑ Malcolm Burrows: Froghopper insects leap to new heights . In: Nature, vol. 424, p. 509 (July 31, 2003).

further reading

- R. Biedermann, R. Niedringhaus: The cicadas of Germany - identification tables for all kinds. Fründ, Scheeßel 2004, ISBN 3-00-012806-9 .

- M. Boulard: Diversité des Auchénorhynques Cicadomorphes Formes, couleurs et comportements (Diversité structurelle ou taxonomique Diversité particulière aux Cicadidés). In: Denisia 4, pp. 171-214, 2002, ISBN 3-85474-077-8 .

- H. Nickel: The leafhoppers and planthoppers of Germany (Hemiptera, Auchenorrhyncha): Patterns and strategies in a highly diverse group of phytophagous insects. Pensoft, Sofia and Moscow, 2003, ISBN 954-642-169-3 .

Web links

photos

additional