School system in South Korea

The South Korean school system has its roots in Confucianism . It has been shaped by various influences throughout history, including Buddhism .

Today the school system is one of the most successful in the world . There are private and public schools where frontal teaching and memorization dominate. In addition, most of the students take private lessons in so-called Hagwons . For a number of years now, there has been great disagreement among academics about the school system, particularly about whether the learning methods are harmful to students.

History of the school system

Time before 1945

The history of Korean schooling can be traced back to about the time of the Three Kingdoms . Even then there were public as well as private schools . Schools and modes of education have been significantly influenced over time by both Confucianism and Buddhism.

The time of the three kingdoms

During the Three Kingdoms Period, there were three kingdoms on the Korean Peninsula . These were Goguryeo (37 BC – 668 AD), Baekje (18 BC – 660 AD) and Silla (57 BC – 918 AD). They were all mutually hostile states . Their educational systems based their type of education in all three realms on Confucianism , Buddhism and the martial arts . A state educational institution was first established in 372 in Goguryeo . This so-called "Daehak" (대학; large school), served to teach the male offspring of the " Yangban " upper class in Chinese literature , history and archery . From the year 427 on, private schools were founded in many cities and provinces . The so-called "Gyeongdang" had the purpose of mainly forming the lower class . In all schools, particular emphasis was placed on social teaching and martial arts . In Silla in particular , great emphasis was placed on training in martial arts. Through this training and other factors, Silla managed to unite the three realms.

Goryeo dynasty

The Goryeo dynasty (918–1392) was strongly influenced by Buddhism in the early years. Over time, however, Confucianism took hold. This can be seen particularly well in the change in the school system. King Gwangjong (949-979) introduced the state examination system "Gwageo" for civil servants (based on the Chinese model of the Tang Dynasty) in 958 . It was taken over to find qualified junior officials for the farm. Under the system, anyone could become a civil servant if they passed the exams. In reality, however, only members of the "Yangban" could do this, as the study for the exams took years.

With the change to Confucianism there was an increasing demand for education. Therefore, in 1127 King Injong (1123–1146) created schools across the country. The University of "Gukjagam" was founded in 992. This was the first university in the country. Over the years the number of universities rose to eleven.

Education flourished throughout the country during the Goryeo Dynasty. With the rise in the level of education, great advances have been made in Korea in printing , as well as in philosophy, literature and the natural sciences. For example, printing with letters made of metal was developed in Korea as early as 1232.

Joseon Dynasty

During the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) Korea became thoroughly Confucian and Neo-Confucian, respectively. As a result, the high government offices could now only be achieved by completing the state examination system.

All over the country there were village schools, the so-called "Seodang" ( 書 堂 , 서당 ), which were not subject to the state education system, but were funded by it. They were designed to teach the lower class a basic understanding of Confucian ethics . The state educational institutions, the so-called "Hanggyeo", then built on these. They were designed to prepare students for state exams for government office.

Then different exams had to be passed. The first exam (sama) was intended for the lower official posts. Then two different paths could be taken to further ascend. There was a civilian career or a military one . During the training, both groups had to pass three difficult exams. A career in the highest government offices at the royal court opened up for the few who passed the final test. According to the theory, all Koreans should have an equal chance to take the exams. In reality, only male members of the respected "Yangban" families reached the top.

The system changed fundamentally in the 15th and 16th centuries, when more and more private schools were founded and these then often deviated from the traditional way of teaching. The practical teaching (實 學, 실학, Silhak) was completely in opposition to Neo-Confucianism and the so-called "Seoweon" ( 書院 , 서원 ) displaced the public schools more and more, until the regent Daewongun (大院君, 대원군, 1863–1873) almost all schools were closed. This was done to strengthen the king's position of power.

In the 19th century more and more Christian missionaries came to the country, but they were not allowed to do missionary work. Because of this, they created many Western-style schools that proclaimed both equality and education for all. These schools were the Wonsanhaksa ( 元山 學 舍 , 원산 학사 ). One of them was the "Gungshin School" ( 궁신 ), which over the years developed into Yonsei University . The violent opening of Korea by Japan in 1876 not only fundamentally changed the country, but also the educational system. The call for Western education was loud across the country. The " Gabo reforms " also greatly changed the education system in Korea. A Ministry of Education was established, which was entrusted with the definition of educational standards and the control of textbook content. This introduced a new state school system, which consisted of a five- to six-year elementary school (小學校, 소학교, Sohakgyo) and a seven-year middle school (Junghakyo). This system abolished the old official exams and thus paved the way for a new era. However, the success of these institutions was largely limited to Seoul, while much of the population relied on the old school system.

In the following years the number of private schools increased, so that in 1909 there were 1,300 schools nationwide. Education thus continued to play a central role in Korean culture and was seen as a requirement for national renewal and social modernization.

Japanese colonial times

While Korea was under the colonial rule of Japan (1910–45), the school system in particular was changed, as this was an important pillar of the integration of the Koreans into the Japanese Empire . The Japanese approach was to "Japaneseize" the Koreans and colonize them forever. For this purpose, the “Joseon Education Decree” (조선 교육령; 朝鮮 敎 育 令) was passed in 1911, which overrode the old school system and made private schools virtually impossible.

The Japanese school system, based on the Prussian model, stipulated that students had to go to elementary and middle school for four years each. After finishing school she should go for professional activities with lower qualifications to be prepared.

Most of the teachers were Japanese and only Japanese was taught. Subjects such as Korean history or geography were forbidden. Furthermore, Koreans found it next to impossible to get a higher education.

With the independence movement of 1919 some small changes were made to the school system. The elementary school was extended to 6 years and the middle school to 5 years. The expansion of the public schools was also promoted, so that in 1936 there was a school in every village. However, a large proportion of Korean middle school and college students attended educational institutions in Japan because opportunities in Korea were too limited.

From the beginning of the war in 1941, the Korean school system was purely Japanese and designed for the war. As a result, many schools were closed at the end of the war.

During the colonial period, the number of public schools increased enormously and the education of the masses was strongly promoted. However, this was only done to raise the Koreans as 2nd class Japanese and to make them dependent on Japan.

Time after 1945

After the end of the war, the educational system of Korea, like the country itself, splits into North and South Korea . Due to the American control over South Korea, a school system based on the American model was introduced accordingly. For the first time in Korean history, this gave the broader population the opportunity to receive free and deregulated education.

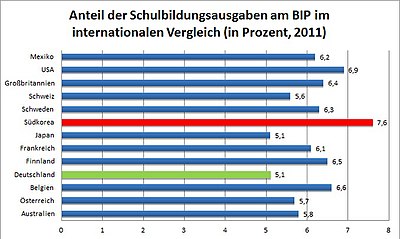

After the founding of the state in 1948, compulsory primary schooling was introduced in 1949 and the 6-3-3-4 system in 1951. The system was based on 6 years of elementary school (Chohakgyo), 3 years of middle school (Junghakgyeo), 3 years of high school (Godeunghakgyo) and 4 years of university (Daehakgyo). However, implementation was difficult due to the lack of qualified teachers and suitable premises. For this reason the government passed a six-year plan in 1954 to remedy the shortcomings. Thus the education budget in the state budget rose from 4.2 percent (1954) to 14.9 percent (1959). As a result of these efforts, an enrollment rate of 95 percent was achieved in 1956.

| year | primary school | Middle school | High school | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class size |

Teacher density |

→ Middle school |

Class size |

Teacher density |

→ Secondary school |

Class size |

Teacher density |

→ Higher education institution |

|

| 1965 | 65.4 | 62.4 | 54.3% | 60.7 | 39.4 | 69.1% | 57.1 | 30.2 | 32.3% |

| 1970 | 62.1 | 56.9 | 66.1% | 32.1 | 42.3 | 70.1% | 58.2 | 29.7 | 26.9% |

| 1975 | 56.7 | 51.8 | 77.2% | 64.5 | 43.2 | 74.7% | 58.6 | 31.4 | 25.8% |

| 1980 | 51.5 | 47.5 | 95.8% | 62.1 | 45.1 | 84.5% | 59.8 | 33.3 | 27.2% |

| 1985 | 44.7 | 38.3 | 99.2% | 61.7 | 40.0 | 90.7% | 56.9 | 31.0 | 36.4% |

| 1990 | 41.4 | 35.3 | 98.8% | 50.2 | 25.4 | 95.7% | 52.8 | 24.6 | 33.2% |

| 1995 | 36.4 | 28.2 | 99.9% | 48.2 | 24.8 | 98.5% | 47.9 | 21.8 | 51.4% |

| 2000 | 35.8 | 28.7 | 99.9% | 38.0 | 20.1 | 99.5% | 42.7 | 19.9 | 68.0% |

| 2003 | 33.9 | 27.1 | 99.9% | 34.8 | 18.6 | 99.5% | 33.1 | 15.3 | 79.7% |

After the basic education was secured, in 1968, under the government of Park Chung-hee (1961–1979), the entrance examination for middle schools was abolished and replaced by a lottery for the places. This happened because there was too much demand for free places and this situation created elite schools. In 1974 the same procedure was introduced for high schools. Initially, however, this led to a deterioration in teaching conditions as class sizes increased (see table). It was not until the 1980s that the expansion of the secondary education sector had progressed far enough to guarantee adequate training. The expansion of secondary education was particularly important for the economic upswing in South Korea, as the country needed well-trained young people.

This soon meant that the universities did not have enough capacity for the increasing demand. The number of students doubled from 1965 (105,000) to 1975 (208,000) and doubled again by 1980 (400,000). For this reason, many new universities were founded or existing ones expanded.

Under the government of President Chun Doo-hwan (1980–1988), an educational reform was passed in 1980 which completely prohibited private tutoring in order to equalize learning conditions. Furthermore, measures were adopted to improve the control of students' extracurricular activities. This was done in order to better control student demonstrations like those that happened under the Park Chung-hee era.

The last change is the Graduation Quota System (GQS), which allowed higher educational institutions to accept 30 percent more applicants than are allowed for the exams. This created increased pressure on the students.

In 1987, the end of the military dictatorship in South Korea was initiated by student protests, which were probably also brought about by the GQ system . The system was abolished in the same year and private tutoring was allowed again in 1990.

Thus, the school system was created here as it still exists today, apart from small changes. From the 1990s onwards, the school system was refined again and again so that lessons could be shifted from pure quantity to ever more quality . For this reason, a government plan, under Kim Young Sam (1993-1998) , was published in 1995, which privatized the school system more and simplified the establishment of universities. This laid the foundation for an "educational glut" in recent years, as the majority of the students now achieve a university degree and thus lose their value in their later professional life.

The structure of the school system today

A large number of scientists see the reason for the rapid South Korean economic growth in its open and competitive education system . However, scientists also see this split: on the one hand, they see success in the education system, on the other hand, they see the education system as one of the biggest problems in South Korean society, as children are confronted with challenges at an early age.

South Korean children between 6 and 15 years of age are required to attend school for 9 years (6 years of elementary school , 3 years of middle school ). Optionally, you can go to secondary school for a further 3 years (then a total of 12 years of schooling). Then you have the opportunity to go to a university. Korean students are required to wear school uniforms in all schools. School classes in South Korea can contain up to 40 students. Korean school lessons are primarily geared towards memorizing the subject matter, the exams and exams are mostly set as multiple-choice tasks.

Korean kindergarten

Pre-education and kindergarten are not required by law in South Korea, but the facility is well attended, except in the rural regions of South Korea. In kindergarten, children are already taught the basics of reading and writing, mathematics and, in some cases, English. Failure to attend kindergarten can cause problems for children in primary school, as this would result in a learning delay.

primary school

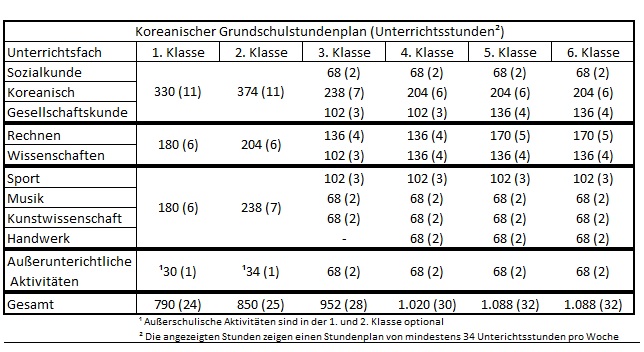

Children start school at the age of 6 or 7, after which they go to primary school for 6 years. In the classroom, the children are already required to be very independent, which means that the teaching is consistently persistent and challenging with the primary school students in a patient, friendly and courteous manner. The teachers are cautious and try not to exceed the general noise level of the class. Lessons focus on Korean, but arithmetic, science and social studies also have a larger share in the Korean elementary school curriculum .

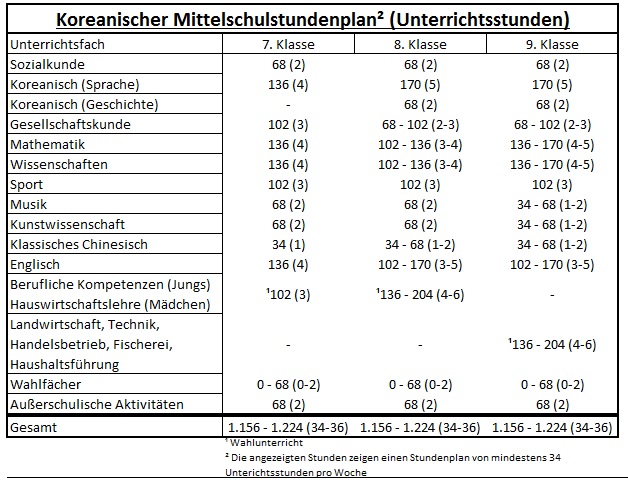

Middle school

The middle school in South Korea is attended from around 12 to 14/15 years of age, i.e. three years of teaching in middle school. The timetable in middle school is broader than the timetable in elementary school. New subjects include Korean history, mathematics, English and Chinese. There are also special classes for boys (vocational skills) and girls (home economics). A total of 13 subjects are taught in the middle school.

High school

High school in South Korea lasts three years (10th to 12th grade) and the students are usually between 15 and 19 years old. The grade point average of the middle school is elementary in order to be accepted at one of the renowned secondary schools. In South Korea there are several types of high schools, which can have different focuses, such as arts and sciences or a foreign language branch. There is tough competition between the high schools. The quality of a high school can be seen from the percentage of graduates who make it to one of the three elite universities, also known as SKY universities ( Seoul National University , Korea University and Yonsei University ). Since it is important to be accepted at a prestigious university, the students also attend the so-called Hagwons after their lessons. There you will receive additional preparation help from tutors for the final exams, as well as extra activities that will make a positive impression in your later application for the university.

University entrance exam

The aim of the 16-hour school day is to pass the university entrance examination ( 수능 Suneung , completely 대학 수학 능력 시험 Daehak suhak neungnyeok siheom , English College Scholastic Ability Test ). This is carried out once a year by the Ministry of Education at the national level. The test should serve the further education of the students, but above all also the universities, which can see through the collected data which students are well suited for their university.

During this examination, knowledge of the last three years of high school is tested over eight hours in the form of a multiple-choice procedure. It is controversial whether a multiple-choice procedure reflects the actual knowledge and qualifications of the student. With this test system one can avoid preferential treatment and unfair treatment. The Suneung is written by all students nationwide at the same time. On this day there is a state of emergency and many offices do not open until after 10 a.m. This will not cause any traffic delays and will not prevent students from taking this crucial exam. Students who are in danger of being late are sometimes escorted to the school by the police. Even air traffic is suspended during the hearing test phase. Parents sometimes stand in front of the schools and pray for their children. Since the pressure on the students is so great, it is not uncommon for suicides to occur because the students cannot withstand the social and family stresses . Around 80 percent of the graduates apply to a university, 80 percent of these 80 percent want to study at private universities. Which university you attend is often more important in your career than which degree you have achieved.

In addition to the regular admission by Suneung, there is also the early admission ( 수시 Susi ). There are three options: Either the secondary school leaving certificate ( 학생부 교과 ) or the entire school performance ( 학생부 종합 ) are taken into account, or an essay ( 논술 ) is expected from the applicant. Due to the level difference between high schools, the final grade is supplemented by the Suneung result. Ie, the applicants must achieve a minimum number of points in Suneung ( 최저 등급제 ); for those who achieve this, however, it is sorted according to the final grade. However, there are also exceptions, for example if the admission of new students is distributed equally across regions. When considering all school achievements, grades, but also extracurricular activities such as social engagement, a cover letter, a letter of recommendation and a motivational interview are included in the assessment. If an essay is accepted, the applicant's essays will be evaluated by the respective university and then accepted or rejected. The essay is not standardized. Here too, the universities often require a minimum number of points in Suneung.

Colleges

After successfully completing the Suneung, high school graduates can apply to various colleges / universities. In contrast to the primary and secondary school levels, there is no school uniform requirement in the colleges / universities. The competition and pressure on the students remain just as high. On the one hand, there are the so-called Jeonmundae, which are universities of applied sciences with a two-year course with a subject-specific focus, and on the other hand, the private and public universities, where you can achieve a bachelor's degree after a four-year course and a master's after another two years . From 1945 to 2001 only the result of the Suneung was used as a means of applying, which put enormous pressure on students and a financial problem for many families. Of course, the result of the Suneung is still important for the application today, but MOEHRD has proposed a new system in which universities can decide for themselves under which criteria they accept students. The following apply as such:

- Record of school activities (grades & social skills)

- College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT)

- University's own test procedures (writing essays, interviews, etc.)

- Letters of recommendation

- Qualifying Examination

- Honourings and prices

There is a big difference in the amount of semester fees between public and private universities . In 2008, Seoul National University tuition was $ 3,730 per year for bachelor's degrees and $ 4,893 per year for masters and doctorates . At the private Korea University, however, it was $ 7,662 per year for a bachelor's degree and $ 11,099 for a master's degree and doctorate. The semester fees in private universities are significantly higher than in comparison to public universities, but these are also better equipped. In 2007, the percentage of high school graduates who applied to universities was 84 percent, which is well above the OECD average of 50 percent. The quota of women at universities was 38 percent in 1995 and has decreased significantly compared to 1975, when the quota of women was 61 percent. After World War II, South Korea worked its way up to become a country with the best education system. In 1943, under the Japanese colonial power , six percent of professors at universities were Koreans; today Korea has a significantly higher proportion with around 220 universities and almost 60,000 professors. The development and importance of studies for a Korean's career can also be seen in the fact that there are more doctoral degrees every year. In 1996 it was around 4786 and in 2001 it was around 6646. The ten leading universities are presented in a ranking .

| Ranking | university | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seoul National University | Seoul |

| 2 | KAIST | Daejeon |

| 3 | Korea University | Seoul |

| 4th | Yonsei University | Seoul |

| 5 | Hanyang University | Seoul |

| 6th | Busan National University | Busan |

| 7th | Ewha Womans University | Seoul |

| 8th | Pohang University of Science and Technology | Pohang |

| 9 | Chung-Ang University | Seoul |

| 10 | Sungkyunkwan University | Seoul |

Hagwon

Hagwons (also known as Academy ) are special, private learning institutes in which there is the possibility of repeating or deepening the subject matter in smaller groups (10 students) than in school (30 to 40 students). However, there are also offers such as dance, writing, painting or rhetoric , which have a positive influence on the application for a university place. These learning institutes are designed to give their visitors the best possible preparation for the Suneung. There are even hagwons for mothers to learn how to best support their children. Since Hagwons are a private company , families pay between 233,000 and 269,000 won a month per subject and child. The tutors themselves earn on average better than teachers who are employed in public schools. While a Hagwon teacher earns between 2.2 and 2.5 million won, a teacher in a public school makes between 2 and 2.2 million won. Especially in Hagwons that offer English, it's not uncommon to have a non-Korean teacher. There are currently almost 100,000 Hagwons in South Korea, which are attended by around 75 percent of all children. After their normal lessons of up to 12 hours, the students go to one of these institutes for another 2 to 4 hours in the evening. Thus, 16 hours of daily study is not uncommon. Especially in the exam phase, Hagwons are also visited on weekends and during the holidays. The reason for the high cost and time a family spends giving their children the opportunity to visit Hagwons is quite simple. The better the preparation for the Suneung, the better the results, which lead to the children being accepted into a renowned university. This increases the social standing and also the reputation for the entire family. However, since the competition for a good education is fierce, applicants for a reputable Hagwon must pass an aptitude test . Though prohibited by law, tutors teach students higher-grade content to give them an edge. Some of the students are already learning material that will not be covered in school for three years. It is not uncommon for first graders to already be able to read, write and do arithmetic and this is taken for granted by the teachers. In an international comparison, Koreans plunge into the cost of private tuition (2.9 trillion won) like no other country because of the madness of good education.

The consequences of the school system

The Korean school system is considered to be one of the best in the world when judged by relevant testing procedures.

After the Korean War (1950–1953), a learning fever broke out in Korea, which continues to this day and also has its downsides. Koreans' urge for the best education defines children's lives from the very beginning. Parents aim to give their children the best possible education so that they can later get a successful job. For children, however, this means having to take a lot of tutoring during elementary school in order to be among the best of the year. The entire education of the children is only aimed at obtaining the best possible result in the aptitude test for the universities. The resulting result indicates whether one can get one of the few and coveted places at one of the elite universities.

But the pressure to perform that is transferred to the children and young people is extremely high. In addition to the long school and tutoring lessons, the children hardly have time to develop creatively. Above all, the children and young people do not want to disappoint their parents, since the family's reputation also depends on their success.

One way that parents see to make their children's lives easier is to give them an education abroad. On the one hand, this has the advantage that it is highly regarded in its own country and, on the other hand, that the children also receive very good language training in English. In these so-called Kirugi families, "wild geese families", the mother and her children live abroad, while the father stays at home to earn money.

Another consequence of the high level of education in the population is that students, even with a university degree, often cannot find any or no adequate employment.

documentation

- Reach for the SKY ( 공부 의 나라 , Damned to Achievement ). Director: Steven Dhoedt , Choi Wooyoung . BEL / ROK 2015.

literature

- Cristel Adick: Educational developments and school systems in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean. Waxmann Verlag, Münster 2013, ISBN 978-3-8309-2785-3 .

- Lee Eun-Jeung, Hannes B. Mosler (Ed.): Country Report Korea. Federal Agency for Civic Education, Bonn August 27, 2015, ISBN 978-3-8389-0577-8 .

- Yugui Guo: Asia's Education Edge, Current Achievements in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China, and India. Lexington Books, UK-Oxford 2005, ISBN 0-7391-0737-2 .

- Thomas Kern: South Korea and North Korea, introduction to history, politics, economy and society. Waxmann Verlag, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-593-37739-X .

- Mee-Jin Kim: Korea etiquette, the door opener for foreign travelers and expatriates. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-486-58531-5 .

- Wolf Dieter Otto: Scientific culture and foreigners, foreign cultural work as a contribution to intercultural education. iudicium Verlag, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-89129-260-0 .

further reading

- Rex Miller, Bill Latham, Brian Cahill: Humanizing the Education Machine, How to create schools that turn disengaged kids into inspired learners. Wiley 2016, ISBN 978-1-119-28310-2 .

- OECD: PISA 2015 Results. Volume I: Excellence and Equity in Education. OECD Publishing, Paris 2016, ISBN 978-92-64-26732-9 .

- OECD: PISA 2015 Results. Volume II: Policies and Practices for Successful Schools. OECD Publishing, Paris 2016, ISBN 978-92-64-26749-7 .

- Gi-Wook Shin, Yeon-Cheon Oh, Rennie J. Moon: Internationalizing Higher Education in Korea, Challenges and Opportunities in Comparative Perspective. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center, 2016, ISBN 978-1-931368-42-1 .

- Yeong-Su Tscheong: The Development of the School System and Problems of Teacher Education in South Korea. Dissertation . Bonn 1984, DNB 850572088 .

- Kye-Za Tschu: School-based vocational training in Korea. Shown using the example of the vocational high school. Dissertation. Hamburg 1984, DNB 850396204 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Yeong-Su Tscheong: The development of the school system and problems of teacher training in South Korea . Bonn 1984, p. 32 ff .

- ↑ a b OECD: PISA 2015 Results (Volume I), Excellence and Equity in Education . Ed .: OECD Publishing Paris. Paris 2016, ISBN 978-92-64-26732-9 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Mee-Jin Kim: Korea-Knigge, the door opener for foreign travelers and expatriates . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-58531-5 , p. 12-32 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Thomas Kern: South Korea and North Korea, Introduction to History, Politics, Economy and Society . Ed .: Patrick Köllner. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-593-37739-X , p. 149-167 .

- ↑ Kye-Za Tschu: School-based vocational training in Korea, illustrated using the example of the vocational high school . Hamburg 1984, p. 10-14 .

- ↑ a b Mee-Jin Kim: Koea-Knigge, The door opener for foreign travelers and expatriates . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-486-58531-5 , p. 81-85 .

- ↑ Wolf Dieter Otto: Scientific culture and foreigners, Foreign cultural work as a contribution to intercultural education . iudicium verlag GmbH, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-89129-260-0 , p. 64 ff .

- ^ A b c Lee Eun-Jeung: Country Report Korea . Ed .: Hannes B. Mosler. 2015, ISBN 978-3-8389-0577-8 , pp. 314-325 .

- ^ Educational System. Retrieved January 29, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c Prof. Dr. Cristel Adick: Educational developments and school systems in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean . Waxmann Verlag GmbH, Münster 2013, ISBN 978-3-8309-2785-3 , p. 93 ff .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Yugui Gui: Asia's Educational Edge, Current Achievements in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China and India . Lexington Books, Oxford 2005, ISBN 0-7391-0737-2 , pp. 89-91 .

- ↑ a b c d Reeta Chakrabarti: South Korea's schools: Long days, high results. BBC, December 2, 2013, accessed January 28, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Fabian Kretschmer: Four hours of sleep? Failed. Taz, November 13, 2014, accessed January 30, 2017 .

- ↑ a b c d e Ok-Hee Jeong: Memorizing into the night. Die Zeit online, November 19, 2013, accessed on January 28, 2017 .

- ^ Elise Hu: Even The Planes Stop Flying For South Korea's National Exam Day. npr one, November 12, 2015, accessed January 30, 2017 (English).

- ^ Point me at the SKY. economist, November 8, 2013, accessed November 30, 2016 .

- ^ Higher Education. moe, 2007, accessed January 30, 2017 .

- ↑ a b Kang Shin-who: Private English Education Cost Rises 12 Percent. korean times, September 27, 2009, accessed January 30, 2017 .

- ↑ Hagwons vs. Public schools. (No longer available online.) 2014, archived from the original on February 4, 2017 ; accessed on January 30, 2017 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ OECD: PISA 2015 Results (Volume II), Policies and Practices for Successful Schools . Ed .: OECD Publishing Paris 2016. Paris 2016, ISBN 978-92-64-26749-7 .

- ↑ South Korea: With Drill for Abitur. Das Erste, Weltspiegel, April 15, 2014, accessed on January 28, 2017 .

- ^ Carsten Germis: Timpani until ten in the evening. Frankfurter Allgemeine, April 23, 2011, accessed January 28, 2017 .

- ↑ Kim Min-sok: Korea needs better education system. The Korean Times, September 16, 2015, accessed January 29, 2017 .

- ↑ High performance, high pressure in South Korea's education system. January 23, 2014, accessed January 30, 2017 .