Shonen

The Japanese term Shōnen ( Japanese 少年 , also Shonen or Shounen , German “boy”, “youth”) describes a category of Japanese comics and animated films, manga and anime , which is aimed at a young male audience. Shōnen is the manga genre most represented on the Japanese market. The related category for a slightly older male audience is his . The counterpart for female adolescents is Shōjo , for adult women Josei . This genre classification according to target groups is due to the fact that most manga in Japan appear first in manga magazines and these have specialized in demographic groups. The classification according to such genres is carried out in the following forms of exploitation such as anthologies and anime films and is therefore widely used beyond the magazines as a rough classification of anime and manga.

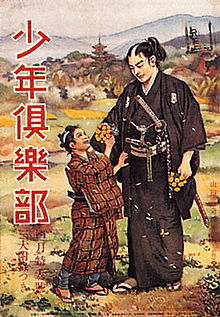

Shōnen originally meant "youth" in general and was used in this sense at the end of the 19th century for children's and youth magazines. The division of the market, especially manga magazines , according to gender and age-specific target groups became established from the beginning of the 20th century, but especially from the 1960s, and is also openly communicated by the publishers. The similar term Bishōnen describes the portrayal of a beautiful young man according to the Japanese ideal, which is particularly common in Shōjo manga and anime.

Target group and readership

Works by the Shōnen are aimed at adolescent boys, the main target group is the ages of 9 to 18 years. As with other demographic categories of anime and manga, the actual readership is far from just the core target group, but is made up of all social groups. In a survey of Manga readers in 2006, for example, most of the Shōnen magazine Weekly Shōnen Jump were their favorites, above all publications aimed at the female target group. The target group orientation is particularly evident in the Shōnen Manga magazines, which, in addition to the series, offer advertising tailored to the interests of young men, for example for games, and additional content. The advertising and other content can usually be assigned to a franchise of the series in the magazine, so in addition to chapters of a manga series, there are advertisements for video game implementation or editorial contributions to film adaptations.

In some series, the female readership consists to a significant extent of recipients who read into or interpret same-sex relationships between the male characters. The characters are especially those who are portrayed as bishons or who are perceived as such by the reader. This reading of the works, which also occurs in the form of fanart such as dōjinshi , is known as Yaoi and has established itself over time as a genre of homoerotic stories including original works. After comparing the female readership of the series One Piece , Naruto and Prince of Tennis and their activity in the form of Yaoi fanart, Yukari Fujimoto comes to the conclusion that the proportion of Yaoi readers tends to be higher in the series that only few, offer weak female figures who are not suitable for identifying the female readership.

Typical elements

The thematic focus of Shōnen is mainly on action, adventure, war and the fight against monsters and evil forces . In some cases, therefore, works are not assigned to the Shōnen because of their target group, but only because their content focus is on action. Despite the thematic focus, there is a great variety of content and a multitude of genres and subgenres within the Shōnen category. Compared to comic cultures outside of Japan, the division offers the greatest thematic variety for its target group. This also includes crime stories, everyday comedies, love stories, romantic comedies and stories about hobbies such as sports and games of all kinds as well as everyday life for many professional groups. The main theme, however, is almost always the rivalry between the protagonist and his opponent. The very dominant action genre presents itself in all possible scenarios, from realistic historical or contemporary representations to fantasy or science fiction . In these, the fight or a quest is often a central element. The most successful representatives of this series is Dragon Ball by Akira Toriyama . Action stories with war themes are often heroic, at the same time there are war and violence critical series. The story of survival after the atomic bomb was dropped barefoot by Hiroshima appeared as a shōnen manga. Historical narratives about samurai focus on humor or the sporting aspect of swordsmanship rather than heroism. In these and other action series, attempts are often made to convey a pacifist message by depicting violence and war. However, it has also been criticized, according to Hayao Miyazaki , that many adventure and action series and films in the genre promise simple solutions and work in good-evil schemes. When a threatening force is torn from the hands of evil and those of the hero, the problem appears to be resolved rather than the force itself being dealt with.

A common hero character, according to Jason Thompson , has "insanely jagged hair", so that his silhouette is slightly different from that of other characters. The character of the heroes is often shaped by contradicting qualities: quick-tempered and cool, serious and cynical, clumsy and infallible - heroes who seem like useless but have hidden abilities. In some series, this contradiction literally takes shape in the form of Henshin . The hero can switch between two personalities here. Examples are Yu-Gi-Oh or Samurai Deeper Kyo . Often associated with this are associations with ghosts, monsters or robots. The hero is often an outsider, someone who is in some way disadvantaged compared to others who, through training, perseverance and willpower, ultimately succeeds against all odds. Another common element of action is therefore the happy ending , but a good ending is not mandatory. The plot itself follows the structure of the hero's journey . The focus in the Shōnen is on the initiation phase, the transformation into a hero, which makes up most of the stories. Accordingly, the further development of the character continues throughout the plot, and the protagonist's outgrowth, becoming a hero instead of being a hero, is the main theme of each series. Angela Drummond-Mathews sees this as an outstanding feature of the Shōnen manga and the reason for its success in Japan. The pattern of the hero's journey is repeated for longer series. In order to maintain the tension, the danger to be overcome becomes greater and the opponent more powerful in each new story arc. In addition to the external goals, such as defeating the opponent, there are also internal goals, such as the protagonist's growing up. The goals of the main characters and the resistances to be overcome are linked, which leads to more complex storylines and character drawings. In contrast to the Shōjo, which focuses on emotions and character development, the stories are quickly driven by dialogue and action.

The depiction of the eyes in the Shōnen, especially in the first decades after the war, is significantly smaller than in the Shōjo. With the latter, the larger eyes are used to better convey emotions - an aspect that is less of a priority for shons. Neil Cohn generally describes the style of drawing in the Shōnen manga as "edgier" than in the Shōjo, so that it can usually be easily distinguished from this by the experienced reader. A stylistic device often used, especially in action scenes, is the contours of the figures drawn in rough, coarse lines, which resemble the lines of movement that usually surround them in these scenes.

The thematic orientation of the genre is easily recognizable from the basic values or the motto that Japanese magazines usually use. In Shōnen Jump these are "friendship, perseverance and victory", the CoroCoro comic for elementary school children calls it "courage, friendship and fighting spirit".

history

Magazines with a separate target group by gender have existed in Japan since around 1900. In 1895, Shōnen Sekai was the first youth magazine, initially aimed at girls and boys alike. From 1902 magazines for girls followed, and Shōnen magazines evolved into products aimed at a male audience. However, these publications did not contain any mangas, these should only develop in the modern form in the following time. Shōnen Pakku from 1907 was the first magazine aimed at boys that also offered manga. In 1914 he was followed by the Shōnen Club , later the Yōnen Club . Among the most successful and influential series in these magazines were Norakuro Nitō Sotsu , which is about the life of a young soldier, and Tank Tankuro , the story of a human, versatile tank in the shape of a sphere. Throughout the 1920s, the magazines had increasing success, and in 1931 Yõnen Club sold over 950,000 copies. However, during the Second World War , sales fell again and the publications were used for war propaganda. The comics became fewer, many of the remaining Shōnen series revolved around samurai and spread patriotic and militaristic ideals. In other stories, robots fought in the war against the United States , just as superheroes went to war there in their stories.

During the occupation , the Japanese publishing industry was rebuilt under initially strict guidelines. Stories of war and combat, as well as many sports, were banned in the media in order to put an end to wartime propaganda. The modern manga developed during this time under the significant influence of Osamu Tezuka with series such as Astro Boy and Kimba, the white lion . Inspired by American cartoons, he created a cinematic narrative style and the tradition of long series with a continuous plot, the story manga , which is also characteristic of Shōnen manga. The series of that time were mostly read by boys and young men and the stories they told were about robots , space travel and heroic action adventures. Some of the science fiction series took ideas from the war comics and implemented them with pacifist ideals, as happened in Tetsujin 28-gō . One of the first new magazines was Manga Shōnen in 1947 , which in addition to Osamu Tezuka also published early works by Leiji Matsumoto and Shōtarō Ishinomori . After the censorship ended in 1952 and a long-lasting economic boom began in Japan, the sales of manga and the number of magazines increased significantly, and in addition to the already established Shōnen-Manga, the genre Shōjo, aimed at girls, slowly established itself . The sport genre , which is strongly represented today, was added to the Shōnen . The first series from 1952 was Igaguri-kun , which was about a judoka. Ashita no Joe , a story about a boxer that was expelled from 1967 to 1973, became the most significant early exponent of the genre. 1959 started the still successful Shōnen Sunday and Shōnen Magazine , the first weekly magazines of the genre. Both were long in competition for the place of the best-selling magazine, and in the 1960s other weekly magazines such as Shōnen Champion , Shōnen King and Shōnen Ace emerged . The long-time best-selling magazine, Weekly Shōnen Jump , has been published since 1968. Many of the most popular or commercially successful shōnen manga were and are published in this magazine, including Dragon Ball , Naruto , Bleach , One Piece and Slam Dunk .

Around 1970 his genre developed for the older male audience, in which many artists of the Gekiga movement found themselves. The decline of the lending library market also contributed to the fact that illustrators switched to the magazine market, bringing their themes and style with them. Some of them switched to the shōnen manga - so here too more serious, political issues were dealt with and more violent and permissive representations and offensive language appeared in the series; Taboos were broken. Notable artists in this movement are Shigeru Mizuki , who created the horror story Gegege no Kitaro , and George Akiyama . In Ashura he addresses and shows cannibalism, in other series it is about traumatized children or mass murderers. Although these mangas aroused opposition from the public, unlike other countries, this did not lead to the decline of the industry, but to greater success. Series with anarchic, offensive humor up to faecal humor became a trend among children's and shonen series from the 1970s. An example that later became internationally known is Crayon Shin-Chan . The founder of erotic series, from which the purely adult-oriented Etchi genre emerged, was Gō Nagai with Harenchi Gakuen , who at that time still appeared in Shōnen Jump .

Both the stylistic and the content differences of the two major categories Shōnen and Shōjo have decreased significantly since the 1980s, there has been a far-reaching exchange of stylistic devices and themes. Big eyes were also used in Shōnen's works to convey emotional states, and female characters were given more important roles, sometimes the main role. Women also began to successfully draw shōnen mangas. Graphic narrative techniques developed in the Shōjo, such as assemblies of several panels, were also common in the Shōnen. As a result of erotic series such as Harenchi Gakuen, as well as by female authors, romance also became part of Shōnen series, especially in the form of romantic comedies. At the beginning of the success of manga in the western world in the early 1990s, the genre was so dominant in these new markets that it shaped the image of manga as a whole. Around 2000 shōjo series gained a lot of popularity, but shōnen is still one of the most popular genres internationally.

In the course of the international publication of manga series, magazines of this genre also emerged outside of Japan. So Sh ō nen Jump also appeared in the United States. The banzai came in German at times ! as well as the Manga Power . None of the publications could stay on the market for a long time.

Position of woman

Originally, men and boys played almost all of the main roles in Shōnen manga, with women and girls, if at all, mostly appearing as sisters, mothers or friends. They formed the "delicate" counterpart to a hard, male world or were objects of desire and disposal of male figures. This is especially true for the Etchi series that developed from the Shōnen manga in the 1970s . Abashiri Ikka by Gō Nagai , one of the earliest exponents of this development, is an early example of a female protagonist. From the 1980s on, women and girls began to take on more important roles. At first, female characters became more active, also fought and were not just accessories. In 1980 published Dr. Slump was the main character of a strong, mischievous girl, a role usually assigned to a boy or a man at the time. At the same time, female artists with shōnen manga first became more popular. These include Kei Kusunoki with horror stories such as Yōma and Rumiko Takahashi with the romantic comedies Ranma ½ and Urusei Yatsura as well as horror stories. More recent shōnen manga that include female protagonists include Fairy Tail , Soul Eater and Watamote .

Especially in series that are also aimed at an older audience, female figures are presented in a particularly attractive way for the male target group, as so-called bishōjos . They are therefore not only an object of emotional or sexual desire for male (main) characters, but also for the potential reader, which makes them part of the fan service . In these series, even more widespread clichés have survived in the past, but women have more active roles here too. A form of romantic comedy that has been established in the Shōnen since the 1980s combines a weak male protagonist with a stronger female figure who is a lover or an object of romantic and sexual interest and who is also a good friend and confidante. In the harem genre , the protagonist is surrounded by several women or girls of different characters who desire him and often appear more confident than himself. Examples are Magister Negi Magi from Ken Akamatsu and Hanaukyo Maid Team from Morishige . Main male characters are not always successful in trying to enter into relationships with female characters. In other cases, the originally naive and infantile male protagonist of the story “grows up” and learns how to deal with women emotionally or sexually. So Yota in Video Girl Ai by Masakazu Katsura . Since the 1990s, women and girls have taken on a more prominent role in Shōnen manga, and female protagonists, while still not the majority, have been common since then.

Manga magazines

Shōnen mangas are published in manga magazines in a target group-oriented manner. During the peak of manga sales in the mid-1990s, there were 23 Shōnen magazines, which together sold 662 million copies in 1995. The entire manga magazine market comprised 265 titles with 1.595 billion copies sold in the same year.

A magazine is usually several hundred pages thick and contains chapters from over a dozen series or short stories as well as advertisements. The most important Japanese shōnen manga magazines are the weekly Shōnen Jump by Shueisha , Shōnen Magazine by Kodansha and Shōnen Sunday by Shogakukan . The three publishers are also the most important manga publishers. The fourth major magazine, albeit by a considerable margin in terms of sales, is Weekly Shōnen Champion by Akita Shoten , which was very important in the 1970s and 1980s and still exists. Also CoroCoro Comic and Comic Bombom be counted among the shōnen magazines, even if they are aimed at a target audience Primary Age and also the child-directed genus Kodomo are attributable. The following is an overview of the best-selling magazines in summer 2015 with a circulation of over 100,000 copies:

| title | printed edition |

|---|---|

| CoroCoro Comic | 920,000 |

| Monthly CoroCoro Comic | 180,000 |

| Jump Square | 260,000 |

| Weekly Shōnen Jump | 2,380,000 |

| Shōnen Magazine | 1,110,000 |

| Monthly Shōnen magazine | 540,000 |

| Weekly Shōnen Sunday | 370,000 |

literature

- Frederik L. Schodt : Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics . Kodansha America, 1983, ISBN 0-87011-752-1 , pp. 68-87. (English)

- Angela Drummond-Mathews: What Boys Will Be: A Study of Shonen Manga. In: Toni Johnson-Woods (Ed.): Manga - An Anthology of Global and Cultural Perspectives . Continuum Publishing, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-8264-2938-4 , pp. 62-76.

- Paul Gravett : Manga - Sixty Years of Japanese Comics . Egmont Manga and Anime, Cologne, 2006, ISBN 3-7704-6549-0 , pp. 52-73.

- Christian Weisgerber: Of fighters and little sisters - gender ideals in beautiful stories . In: Mae Michiko, Elisabeth Scherer, Katharina Hülsmann (eds.): Japanese popular culture and gender: A study book. Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 2016, ISBN 978-3-658-10062-9 , pp. 75-96.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Miriam Brunner: Manga . Wilhelm Fink, Paderborn 2010, ISBN 978-3-7705-4832-3 , p. 116 .

- ↑ Trish Ledoux, Doug Ranney: The Complete Anime Guide . Tiger Mountain Press, Issaquah 1995, ISBN 0-9649542-3-0 , pp. 212 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Jason Thompson: Manga. The Complete Guide . Del Rey, New York 2007, ISBN 978-0-345-48590-8 , pp. 338-340 .

- ^ A b Antonia Levi: Antonia Levi: Samurai from Outer Space - Understanding Japanese Animation . Carus Publishing, 1996, ISBN 0-8126-9332-9 , pp. 163 .

- ↑ a b Yukari Fujimoto: Women in "Naruto" Women Reading "Naruto" . In: Jaqueline Berndt and Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer (eds.): Manga's Cultural Crossroads . Routledge, New York 2013, ISBN 978-0-415-50450-8 , pp. 172, 184 .

- ^ Toni Johnson-Woods: Introduction . In: Toni Johnson-Woods (Ed.): Manga - An Anthology of Global and Cultural Perspectives . Continuum Publishing, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-8264-2938-4 , pp. 8 .

- ^ A b c Nicholas A. Theisen: The Problematic Gendering of Shōnen Manga. In: What is Manga. May 27, 2013, accessed September 17, 2015 .

- ^ McCarthy, 2014, p. 26.

- ↑ Brunner, 2010, p. 62.

- ↑ a b c d e Drummond-Mathews, 2010, pp. 62–64.

- ↑ Brunner, 2010, p. 73.

- ↑ Andreas C. Knigge : Comics - From mass paper to multimedia adventure . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1996, ISBN 3-499-16519-8 , pp. 247 .

- ↑ a b c d Levi, 1996, p. 9.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Gravett, 2006, pp. 52–59.

- ↑ a b Drummond-Mathews, 2010, pp. 64-68.

- ↑ Thomas Lamarre : The Anime Machine. A Media Theory of Animation . University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 2009, ISBN 978-0-8166-5154-2 , pp. 51 f .

- ↑ a b c Drummond-Mathews, 2010, pp. 70-75.

- ↑ a b c Jennifer Prough: Shōjo Manga in Japan and Abroad . In: Toni Johnson-Woods (Ed.): Manga - An Anthology of Global and Cultural Perspectives . Continuum Publishing, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-8264-2938-4 , pp. 94, 97 .

- ^ Neil Cohn: Japanese Visual Language . In: Toni Johnson-Woods (Ed.): Manga - An Anthology of Global and Cultural Perspectives . Continuum Publishing, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0-8264-2938-4 , pp. 189 .

- ↑ Gan Sheuo Hui: Auteur and Anime as Seen in the Naruto TV Series . In: Jaqueline Berndt and Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer (eds.): Manga's Cultural Crossroads . Routledge, New York 2013, ISBN 978-0-415-50450-8 , pp. 229 .

- ↑ a b c Frederik L. Schodt : Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga . Diane Pub Co., 1996, ISBN 0-7567-5168-3 , pp. 82-84 .

- ↑ Helen McCarthy: A Brief History of Manga . ilex, Lewes 2014, ISBN 978-1-78157-098-2 , pp. 12 f .

- ^ McCarthy, 2014, pp. 16-21.

- ↑ Schodt, 1983, p. 51.

- ^ Matt Thorn : A History of Manga. Matt-thorn.com, June 1996, accessed March 18, 2013 .

- ↑ Kōdansha intānashonaru: Eibun nihon shōjiten: Japan Profile of a nation . Revised ed., 1st ed. Kōdansha Intānashonaru, Tōkyō 1999, ISBN 4-7700-2384-7 , p. 692-715 .

- ↑ Frederik L. Schodt: The Astro Boy essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the manga / anime revolution . Stone Bridge Press, Berkeley, Calif. 2007, ISBN 978-1-933330-54-9 .

- ↑ Schodt, 1983 , pp. 64-66.

- ^ McCarthy, 2014, p. 24.

- ↑ a b McCarthy, 2014, pp. 28–34.

- ↑ 2009 Japanese Manga Magazine Circulation Numbers. Anime News Network , January 18, 2010, accessed October 30, 2011 : "The bestselling manga magazine, Shueisha's Weekly Shonen Jump, rose in circulation from 2.79 million copies to 2.81 million."

- ↑ George Akiyama: the unstoppable King of Trauma Manga. ComiPress, November 24, 2007, accessed September 6, 2015 .

- ↑ Lambiek Comiclopedia: Comic Creator: Go Nagai . Lambiek . Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ↑ Ryan Connel: 40-year veteran of ecchi manga Go Nagai says brains more fun than boobs . Mainichi Newspapers Co .. March 30, 2007. Archived from the original on March 17, 2008. Retrieved on April 12, 2008.

- ↑ Levi, 1996, p. 14 f.

- ↑ Thompson, 2007, p. 301.

- ↑ a b Schodt, 1983, p. 75.

- ↑ Trish Ledoux, Doug Ranney: The Complete Anime Guide . Tiger Mountain Press, Issaquah 1995, ISBN 0-9649542-3-0 , pp. 56 .

- ↑ Thomas Lamarre : The Anime Machine. A Media Theory of Animation . University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 2009, ISBN 978-0-8166-5154-2 , pp. 216 f .

- ↑ Perper, Timothy and Martha Cornog. 2007. "The education of desire: Futari etchi and the globalization of sexual tolerance." Mechademia: An Annual Forum for Anime, Manga, and Fan Arts. 2, pp. 201-214.

- ↑ Schodt, 1983, p. 13.

- ↑ 印刷 部 数 公 表. j-magazine.or.jp, October 1, 2015, accessed December 12, 2015 (Japanese).