Simitthu

Coordinates: 36 ° 29 ′ 30.8 " N , 8 ° 34 ′ 34.3" E

Simitthu (also Simithu or Simitthus ), today's Chimtou (or Chemtou ) in northwestern Tunisia , was a city in the province of Africa proconsularis in ancient times . The settlement history reaches at least 4/5. Century BC Until the 9th / 10th Century AD, however, the place was best known for its quarries, in which the yellow marble numidicum or giallo antico , one of the most valued marbles of the Roman Empire, was mined .

Localization and geology

Chimtou is located in the far northwest of Tunisia, about 23 kilometers west of the provincial capital Jendouba . It is located on the central reaches of the Oued Medjerda (Roman Bagradas), the largest ever water-bearing river in the country. The upper Medjerda plain is still the most productive agricultural area in Tunisia. The regularly cut river valley is bordered in the west and north by high forested mountains, in the south by flatter ridges.

The Djebel Chemtou (Arabic: Djebel / Jebel: mountain , mountain ), a rocky ridge over two kilometers long, is less than 15 kilometers from the western edge of the valley from the northern edge of the mountains. It is a multifaceted, rugged limestone massif that is discolored red on the surface by iron oxides . Its south-western tip pushes itself directly against the high steep walls of the Oued Medjerda. The flat spur of the rock ridge forms a plateau protected from flooding directly at the ford . It is 400 meters wide, towers 85 meters above the river level at its highest point and dominates the upper Medjerda valley as a prominent landmark.

The Djebel Chemtou is over a kilometer long from the limestone that was to be known as yellow Numidian marble in ancient times . It was discovered and dismantled in pre-Roman times. Many fracture zones are carved into the rock ridge in steep corridors and together form the largest ancient marble quarries in North Africa . The marble comes in all variants of yellow, pink and red and is characterized by its veins, layered sintered ribbons and moving breccia structures. In the color spectrum of ancient gems it is without comparison and therefore also known under the name marmor numidicum . In the Diocletian price edict from the end of the 3rd century AD, the giallo antico ranks third among the 18 listed varieties with 200 denarii per cubic foot (a cube with a side length of 29.42 centimeters).

The marble massif is staggered in three ways: the eastern tip is known as the Temple Mount , the middle one as the Yellow Mountain and the western one as the City Mountain . On the Temple Mount was in the 2nd century BC. Marble was discovered as a building material for the first time in BC, later the greatest breaking activity took place on the Yellow Mountain. The Numidian-Punic settlement was on the city hill. The dimensions of the settlement are still unknown today. The later Roman Colonia Iulia Augusta Numidica Simitthensium spread like a clip around the western spur of the mountain.

Settlement history

Chimtou is best known for marble quarrying in Roman times, but the region was continuously settled from prehistoric times and drew its wealth from the great agricultural fertility of the Medjerda Valley. Already in pre-Roman times there was a brisk mining of raw materials. Black marble and limestone were mined in Ain el Ksair, green limestone at the nearby Byzantine settlement of Bordj Hallel and yellow sandstone in Thuburnica .

Punic-Numidian settlement

The Numidian settlement with streets, canals and residential areas was discovered in the 1980s in the area of the Roman Forum . It was at the intersection of two important roads from Carthage to Hippo Regius and from Thabarca to Sicca Veneria and a river crossing and existed from the early 2nd century BC. BC to the 1st century AD. It was influenced by the Punic , which can be seen in the construction and the system of measurement used . A pre-Roman necropolis from the 4th to 1st century BC, preserved under the Roman forum, belongs to it. BC with monumental grave structures that have been partially reconstructed. Extensive trade contacts in the Mediterranean area had existed since the time of its creation and the giallo antico was systematically obtained from here .

Roman city

The city became a Municipium at the beginning of the imperial era and around 27 BC. Chr. Colonia with the name "Colonia Iulia Augusta Numidica Simithu". In the 1st century BC In BC, under Augustus , the new owner of the quarries, the quarrying began on a large scale. Marble numidicum was in demand as a luxury item in the Roman upper class (and later it had an excellent reputation among the Italians as a giallo antico ). It was coveted for magnificent imperial buildings and was shipped to Rome . The residential town developed in parallel with the flourishing of the quarries. Simitthus prospered in the High Imperial Era and reached its heyday under the Severians . During this time, a redesign and monumentalization takes place, as can also be observed in other North African cities. This was followed by a late antique phase, which leads over the Vandalic and Byzantine times into the early Middle Ages . The public function of the area was given up no later than in the 7th century AD. The extinction of urban life in the 7th century AD can also be observed in other settlements in the province. The most recent large-scale settlement structures are early Arabic and date from the Aghlabic and Fatimid periods, i.e. the 9th and 10th centuries AD.

Monuments

The evidence of the long history of Chimtou's settlement has been partially preserved on the rocky ridges or on their south, west and north slopes. In Simitthus there were all those buildings that can be regularly found in Roman cities: an amphitheater , a stage theater, a forum with a forum basilica and fountain , a three-aisled market hall , a nymphaeum , at least three thermal complexes (city baths), several arches of honor , at least five early Christian -Byzantine church buildings and a building interpreted as an imperial cult building in the northwest of the city, which is most likely a so-called Italian Podium temple or temple italique . There were also two other Roman sanctuaries on Djebel Bou Rfifa , the temple districts of Dii Mauri on the eastern slope and the Caelestis on the western slope.

In addition, Simitthus also had some buildings that stand out due to their uniqueness in the North African region:

Numidian altitude monument

On the summit of the Temple Mount / Djebel Chimtou there is a Numidian high-altitude sanctuary, which is attributed to the Numidian king Micipsa . His father Massinissa , who had been an ally of Rome since the Second Punic War , had around 152 BC. Took power over the upper Medjerda valley. After his death, his son and successor Micipsa donated him to him in the late 2nd century BC. A ten meter high monumental altar on the highest point of the mountain. The marble in question served as building material, which also meant the discovery of the marble numidicum . The ground plan of the high altitude sanctuary is a rectangle about twelve by five and a half meters long and wide. It was built on the leveled bedrock , the crevices and unevenness of which were closed with ashlar settlements . The building consisted of massive marble blocks connected with dowels and had no interior space. Only a few blocks of the foundation have been preserved in situ .

The monument consisted of a high substructure, which was oriented due east to the rising sun. A false door to which a three-tier plinth led was attached to its long eastern side. On the substructure was a second floor, which was designed as a Doric pillar pavilion. The building was richly decorated, including a trophy relief . The fragments of the building decoration are among the most valuable examples of the only extremely rarely preserved Numidian royal architecture and can be seen today in the museum of Chimtou at the reconstruction of the high-altitude sanctuary.

In Roman times, the high sanctuary continued to be used as a temple dedicated to the god Saturn . In the late 2nd century AD it was expanded with various additions and was finally replaced by a small, three-aisled church in the 4th century AD , using the blocks and architectural parts of the destroyed sanctuary .

Rock reliefs

At the end of the 1960s, the largest known series of Roman rock reliefs in North Africa was discovered on the Temple Mount . There are around 200 pieces in total. They are chiseled out of the rock in the southwest, west and north of the Temple Mount, heavily weathered and only visible when light falls at an angle. The reliefs mostly depict the same thing: the consecrator, an altar , a sacrificial animal , which - if recognizable - is always a ram . The consecrator is often shown riding on the sacrificial animal and with the attributes rhombus and wreath . Although no inscriptions were found, the typology points to the god Saturn. Reliefs dedicated to him constitute one of the largest classes of monuments in North Africa . The reliefs are arranged in groups and are, if possible, on natural rock banks. Often there was a niche directly in front of it where dedicatory offerings could be placed. In one case, shards of several vessels and a clay lamp were discovered.

Medjerda Bridge

The Roman bridge over the Medjerda is considered the largest bridge structure in North Africa and is of outstanding importance from an architectural-historical and engineering point of view. It led the Roman road connection between Thuburnica and Sicca Veneria over the Medjerda near Simitthus. In the alluvial land of the strongly meandering river, the difficult foundation conditions and the annually recurring floods made construction a risky undertaking. The first attempt to build a bridge was made in the 1st century AD, but this first bridge did not last beyond the century. A new building was donated by Trajan in 112 AD , as can be seen from a dedicatory inscription (it is now in the Chimtou Museum). The river was probably diverted temporarily to build the bridge. A 30 meter wide and 1.5 meter thick foundation slab made of wooden boxes filled with a lime-mortar-stone mixture ( Caementicium ) was placed on the river bed . Its top was secured with a covering of stone blocks. However, this construction was heavily stressed by the strongly changing water flow and was therefore later reinforced. However, the fortification measures could not stop the submergence of the plateau, which ultimately led to the collapse of the bridge in the 4th century. Since then, the remains of the building have formed an impressive field of rubble.

The bridge had three arch openings, only one of which served as a water passage, so that it was also a dam . Only the southernmost bridge pillar is still in its original place. Greenish limestone from Bordj Helal, gray marble / limestone from Ain El Ksir and yellow stone blocks of unknown origin were used as the material for the blocks.

Turbine mill

About a century after the bridge was inaugurated, a turbine- powered flour mill was built on the left bank . It is one of only two known Roman turbine mills in North Africa (the second is in Testour ). It was a rectangular block building protected by the high bridgehead . The wooden turbines had horizontally mounted paddle wheels, three millstones were attached directly to the turbine axles. The construction, previously unknown from antiquity, worked in a clever way: if the river level and thus the flow speed in summer were too low to drive the mill wheels, the water was initially dammed in an adjustable mill pond. It was then directed into mill passages which, like nozzles , narrowed sharply and accelerated in them, so that the mill worked all year round. When the bridge collapsed in the first half of the 4th century AD, the mill building was also destroyed and the mill pond was closed so that the system was no longer functional.

Labor camp

A labor, residential and administrative camp was necessary for the centrally organized marble quarrying , which was laid out on the northern edge of the quarry , 800 meters from the Roman city, on an area of over 40,000 square meters. On the huge camp area there were stacking rooms, apartments, stables , workshops , bathhouses , sanctuaries, water distributors and, directly in front of the 300 meter long south wall, a separate cemetery for the camp residents (the urban necropolis was on the southern slope of the Djebel Chemtou). These were often judges sentenced "to the quarries", e. B. After the turn of the ages persecuted Christians (including women). They were buried in simple stone graves with modest burial mounds . The storage area was surrounded by a high, heavy wall, at which only two gate entrances have so far been found. Although the labor camp was so hermetically separated from the city, it benefited from it: chiefs of the quarries donated public buildings to the place, but not made of marble blocks, because they were too expensive and intended for export . The largest structure in the camp was a 3000 square meter factory or fabrica, which was separated from the camp itself by heavy walls. It was divided into six elongated workshop axes that could only be entered individually through six lockable gates and were not connected to one another. More than 5000 stone objects of various kinds were found here, which testify to a real mass production: In addition to slabs and blocks of marble blanks, plates, make-up pallets, inlays, mortars, pestles, relief bowls and statuettes were made here for both everyday use and for export. Some of the ground shells had walls only 2 millimeters thick. The complex was built in the penultimate third of the 2nd century AD and only provided with its own water pipe inside at the turn of the century . As early as the middle of the 3rd century, however, an earthquake caused the vaults and flat ceilings of the multi-aisled complex to collapse. As a result, the Fabrica was only poorly restored in parts and existed under unclear conditions until the end of the century. It is likely that the workers no longer lived in the camp area in this last phase, as no more graves are being laid in the camp cemetery. In the 4th century, the camp walls were systematically looted for building material and the camp was then completely leveled.

Cisterns and aqueducts

As in every Roman city, there was an urban aqueduct in Simitthus , from which public and private baths, drinking water fountains and show fountains were fed. In Simitthus, however, in contrast to other Roman cities, there was an increased demand for water, since not only the residential town had to be regularly supplied with fresh spring water, but also the quarries: in the quarry, in the labor camp and in the Fabrica it was sawing, grinding, forging of tools and drinking water for the workers constantly needed. Simitthus therefore had an unusually elaborate aqueduct: the water was transported to the city over a distance of more than 30 kilometers with bridges, pillar arcades and underground canals. There it was directed to a “Castellum divisorum” located almost 2 kilometers outside the city. This is a huge, arched seven-aisled water reservoir and distributor with large window openings for ventilation. Here over 10,000 cubic meters of water could be stored and distributed as required. The aqueduct led in on the north wall and on the slope side in the east adjustable lines led south to the city and to the quarries.

Research history

19th century French research

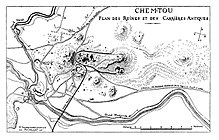

The oldest known survey of the terrain comes from the French engineer Philippe Caillat. He drew a map of the ruins and the site for the epigrapher René Cagnat , who visited Chimtou in 1882. In 1885 the ruins were documented again, this time by the French architect Henri Saladin . His version was the most complete to date and was based on Charles Emont's revised Caillat plan. The first archaeological excavations were carried out in 1892 by the French archaeologist Jules Toutain , who examined parts of the Roman theater . However, the work was stopped again after a short time.

German-Tunisian cooperation

In 1965 the first German-Tunisian excavation campaign finally began in Chimtou. The then Institut National d'Art et d'Archéologie INAA (today: Institut National du Patrimoine INP) and the German Archaeological Institute in Rome worked together. The German excavations in Simitthus are closely related to the name of Friedrich Rakob , who was the head of the German side from the beginning of the German-Tunisian cooperation project. During the work, particular interest was initially given to the exploration of the quarry and its development history and technology. The numidian sanctuary as well as two other Roman sanctuaries were discovered on Djebel Bou Rfifa. The excavators also became aware of the rock reliefs in the late 1960s. However, questions relating to urban infrastructure and development were soon followed up. In the 1970s, the labor camp was located on the basis of aerial archaeological studies. The recording and documentation of a large part of the Roman infrastructure also fell during this period. Research activities also focused on the pre-Roman necropolis preserved under the Roman forum . The first traces of the associated Numidian settlement were discovered in the 1980s. Further research is the aim of the work that began in 2008. In 1998 the labor camp was the target of excavations under the direction of Michael Mackensen , University of Munich .

Museum in Chimtou

From 1992 an archaeological museum was set up in Chimtou and inaugurated in 1997: the Musée Archéologique de Chimtou. During the construction work there was a spectacular gold find of 1,447 coins from Roman times in 1993. The results of research from 1965 to 1995 are exhibited in the museum. In the central courtyard, the reconstructed facade of the Hellenistic-Numidian high-altitude monument can be seen with the significant fragments of architectural decoration from the 2nd century BC. Can be viewed in original size. In addition, a film was made in 1999 that summarizes the research results between 1965 and 1999 in five different languages.

New work

The focus of the latest work since 2008, under the direction of Philipp von Rummel ( DAI Rome ) and Mustapha Khanoussi (INP Tunis), is now the question of the development of the city in the previously largely unknown early and late phase of the settlement. The first important results for the pre-Roman phase could be achieved in 1980–1984 north of the forum by CB Rüger . The aim of the current project is both the publication of these older results and their confrontation with new questions, which are taken into account, among other things, by expanding the excavation area. The work mainly focuses on the area of the forum, the Medjerda bridge and the so-called imperial cult temple . In addition, there is the processing and publication of the late antique coin treasure that came to light during construction work on the museum.

Others

Simitthu is a titular bishopric of the Catholic Church.

literature

- Azedine Beschaouch among others: The quarries and the ancient city . Zabern, Mainz 1993 (Simitthus, 1), ISBN 3-8053-1500-7 .

- Mustapha Khanoussi ao: The Temple Mount and the Roman Camp . Zabern, Mainz 1994 (Simitthus, 2), ISBN 3-8053-1625-9 .

- Michael Mackensen : Military camp or marble workshops. New investigations in the eastern area of the Simitthus / Chemtou von Zabern labor and quarry camp , Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-8053-3461-3 ( Simitthus, 3 ).

- Hans Roland Baldus, Mustapha Khanoussi: The late antique coin treasure from Simitthus / Chimtou Reichert, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-95490-068-8 ( Simitthus, 4 ).

- Ulrike Hess, Klaus Müller and Mustapha Khanoussi: The bridge over the Majrada in Chimtou Reichert, Wiesbaden 2017, ISBN 978-3-95490-246-0 ( Simitthus, 5 ).

- Friedrich Rakob : Chemtou - From the Roman world of work. In: Ancient World. Journal of Archeology and Cultural History. Volume 28, No. 1, 1997, pp. 1-20.

- Friedrich Rakob, Theodor Kraus: Chemtou. In: You. The art magazine. Volume 3, 1979, 36-70.

- Friedrich Rakob, Numidic Royal Architecture in North Africa in: HG Horn, Ch. B. Rüger (Ed.), Die Numider (Bonn 1979) 119–171.

- H. Saladin: Chemtou (Simitthus). In: Nouvelles archives des missions scientifiques et littéraires. Volume 2, 1892, pp. 385-427.

- J. Toutain: Le theater romain de Simitthu. In: MEFRA. Volume 12, 1892, pp. 359-369.

Web links

- Chimtou Museum and Chimtou Ancient Sites

- Online bibliography on Simitthus (Chimtou)

- Roman turbine mills

- Chemtou in the picture

- New excavations by the German Archaeological Institute in Chimtou

Individual evidence

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 39

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 40

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 43

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 48

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 59

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 59

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 62

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 63

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 52

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 66

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 66

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 55

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 57

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 66

- ↑ Rakob, Kraus 1979, p. 67

- ↑ Mackensen 2005, p. 1