Textual criticism of the New Testament

The textual criticism of the New Testament serves to reconstruct the most original version of the texts from the abundance of text variants in the handwritten tradition of the New Testament . For this purpose it uses the same scientific methods as Classical Philology . However, it is a special case due to the disproportionately higher number of old manuscripts compared to any other ancient text.

General

The textual criticism of the New Testament belongs to the methodological canon of historical-critical biblical research. However, in contrast to the other work steps of the historical-critical methods, it is also accepted by many evangelical and fundamentalist groups.

The (general) textual criticism was developed by classical philology in order to reconstruct ancient texts, some of which are only fragmentary but have been handed down in several lines of tradition. As the textual history of the New Testament shows, the New Testament is far better attested than any other ancient text. The New Testament is a special case in textual criticism due to the large number of text witnesses and because of the impossibility of creating a complete tradition.

The New Testament was originally not written and handed down as a complete script. The individual writings were created in different places and at different times, were later combined into four larger text corpora and only long afterwards were combined into an entire codex .

The four parts are:

- the four gospels ;

- the Catholic letters (Corpus Apostolicum), often together with the Acts of the Apostles ;

- the Corpus Paulinum , to which the Letter to the Hebrews belongs in the textual criticism ;

- the apocalypse of John, it was handed down as a single book.

Many manuscripts therefore only contain individual parts of the New Testament. Complete manuscripts are based on different templates in the individual parts. A complete manuscript can have a good text in the Gospels, but an error-prone text in the remaining parts, or vice versa. The different traditions of the individual parts are reflected up to modern times, which even in the printed editions does not yet show a uniform order of the books.

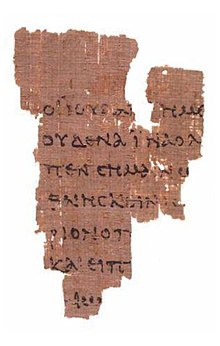

Most of the New Testament autographs were written between the middle and the end of the 1st century, a few at the beginning of the 2nd century AD. The autographs are lost today and only copies have survived. The first known papyrus fragments are from the beginning of the 2nd century. The first quotations from the Church Fathers and translations into other languages a little later come from this time . The first completely preserved text witnesses are written on parchment and date from the 4th century.

There are over 5,000 text witnesses in Greek, over 10,000 Latin manuscripts, and another 10,000 manuscripts of translations into other languages. The texts are also often quoted by the Church Fathers , but also by authors who are considered heretical, such as Marcion or Gnostic authors.

The copyists often changed the templates, worked with several templates at the same time, or later corrected the copy on other templates. This means that many manuscripts do not have one, but several origins, which is known as contamination. The creation of a stemma, i.e. a family tree of the manuscripts, is therefore very difficult and sometimes not possible. Today's New Testament text critics circumvent the problem by sorting the text witnesses into groups called text types. The main text types are the Alexandrian type , the Western type, and the Byzantine type .

method

Briefly described, the textual criticism proceeds roughly as follows:

- The text of the manuscripts is reconstructed and deciphered.

- The existing manuscripts are compared with one another and variants are identified (collation).

- The variants are analyzed, particularly with regard to their origin. Experience has shown that the following occur:

- Accidental copying (duplicate lines or words ( dittography ), omitted lines or words ( haplography ), confusion of similar letters, spelling mistakes);

- a difficult text has been simplified;

- a short text was added;

- an unusual text has been aligned with a common one (e.g. Christ Jesus becomes Jesus Christ) or in the synoptic Gospels the readings are aligned with one another;

- a change due to Itazism , triggered by the sound changes in the Greek language.

- A variant that is as original as possible is determined. The more original reading is considered to be the one that can best explain how the other readings came about (comparable to phylogeny ). Other factors are also the age or the quality of a manuscript: a papyrus is often older than a parchment and a minuscule manuscript is usually younger than a capitals , so the text witnesses have different weight and different credibility when it comes to the more original reading. However, a young copy can also have a very good and old model.

- A very large part of the text-critical decisions concern insignificant details that have no effect on the meaning or the subsequent translation. This applies, for example, when a text replaces the pronoun with the reference word, the order of the words in the sentence is changed or when words are spelled together or separately. This also applies in most cases to accents, diacritical marks or punctuation marks.

- Conjectures , i.e. readings proposed by the editor without a traditional text basis, are no longer justified in the current research situation in New Testament science. Today it can be assumed that at least one known text witness contains the original reading at the point in question, or at least one reading that comes very close to the original text.

- Even the best witnesses should be questioned. No text witness is right always and everywhere and every writer can make mistakes. Each text passage with a different reading must be viewed individually and the decision made and justified each time individually.

- Text-critical decisions mainly based on the majority of known text witnesses no longer correspond to the state of modern text criticism. The number of text witnesses depends mainly on which tradition has prevailed over time and is to a certain extent random. In some cases, entire groups of manuscripts, so-called text families, can be traced back to a single or very few originals. In this case, only the one model that can be reconstructed from the copies is of text-critical value, although it in turn goes back further in time than the traditional manuscripts.

All this work flows into the so-called apparatus of a Greek text edition , with which the reliability of the text can be assessed. The possible variants of a Bible verse are given in footnotes, the text witnesses in which the variants appear, and usually an evaluation of the variant.

Textual criticism is not interested in the interpretation of the content of the text, but rather, as a first step within historical-critical exegesis, provides the text to be analyzed further. Textual criticism can only be dispensed with if the textual form of a certain tradition has been determined as binding by a dogmatic decision. Friedrich Blass says of the textual criticism: "Because really, it is not necessary neither for national prosperity, as money-making is nobly called, nor for the whole mechanism of modern life, nor for the mechanism of the Church, nor, as I said, for the bliss of souls; why is it necessary at all? It is, I say, for reasonable and educated people, or in other words for thinking Christians. "

In the beginning, textual criticism is understood primarily as a return to the origins. The aim is to eliminate the later additions as secondary or even as adulteration. Textual criticism, on the other hand, is seen as a necessary evil of the diverse tradition. The textual review reconstructs the tradition of the New Testament text with its translations, glossings , additions and changes. The diverse tradition can thus be seen not only as a lack, but also as a wealth. Text extensions and changes are to be understood as an interpretation and understanding of the templates and text variants are understood as part of the hermeneutics and the history of interpretation.

History of Textual Criticism

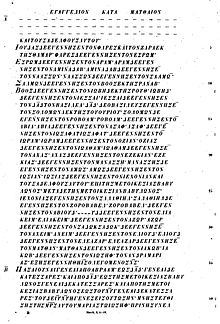

The first printed editions and the Textus Receptus

With the advent of the printing press and modern translations, the question of the correct biblical text became particularly important. Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros printed the Greek text for the first time in the Complutensic Polyglot in 1514 with great personal and financial commitment. However, until 1520 there was no papal permission to publish the print. He himself died in 1517. The first commercially available printed edition, Novum Instrumentum omne of the Greek New Testament by Erasmus of Rotterdam , appeared in 1516 and established the Textus Receptus that was later to be called . It was based on only a few rather randomly selected and comparatively young manuscripts of the Byzantine type, also on the Vulgate . Erasmus translated the Vulgate back into Greek in some places and created some new terms, which, however, lasted for a long time. The second edition of 1519 became the basis of the Luther Bible .

Théodore de Bèze , also known as Beza in German usage, dealt with various manuscripts and found the Codex Bezae from the 5th century, the oldest known text witness of the western type at its time, which contains some unusual readings. Beza published several text editions, but they are also still considered Textus Receptus. He feared confusion among Bible readers and therefore used the Codex Bezae little. The French printer Robert Estienne , in German usage also Stephanus, was the first to print the readings of the older text witnesses Codex Bezae and Codex Regius in his Editio Regia . In 1551 he introduced verse counting, which is still common in all Bible editions today . The editions of Stephanus and Bezas have been reprinted in their text in many ways and have served as the basis for many translations such as the English King James Bible .

The beginnings of science in the 18th century

Of the many editions of the Textus Receptus, the edition by John Mill stands out because he lists the readings of numerous text witnesses in a continuous context and at the same time enables the reader to assign the readings to the various text witnesses. He was also the first to give the exact signatures and storage locations of the manuscripts used, as well as the characteristics, age, and quality of the manuscripts, thus providing clues for text-critical decisions for the first time. His work lasted 30 years. Mill died two weeks after he published his New Testament in 1707.

Due to the lack of access to the older manuscripts, Johann Albrecht Bengel was only able to deal with about two dozen relatively unimportant manuscripts in detail, but he was able to use Mill's findings. He gave some rules for textual criticism that are still valid today outside of theology. In 1725, in the Prodromus NTG adornandi, he set the rule to Proclivi scriptioni praestat ardua (the darker spelling precedes the light), today it is also known as lectio difficilior (the more difficult reading). Bengel was the first to establish the rule that text witnesses should not be counted when making text-critical decisions, but rather weighed ( manuscripti non sunt numeratur sed ponderatur ). He also developed the method of creating family trees (stemmata) for the manuscripts. He recognized basic families of texts and called one African and the other Asian, forerunners of the text types used today. For his text edition from 1734 he identified the manuscripts that Erasmus used, including their shortcomings. He noticed various errors in the text and made suggestions for improvement in the apparatus. However, he did not want to include a reading in the main text that had not already appeared in print. Most of his suggestions for improvement later turned out to be correct with a better text basis.

Johann Jakob Wettstein published his text edition from 1751 to 1752, which was later reprinted several times. The text-critical apparatus was more detailed than in any other edition so far. He marked the older manuscripts with Latin letters and the younger ones with Arabic numerals. It provides a wealth of information on the manuscripts, the translations and parallel passages. Wettstein also refined and intensified the use of palaeography in order to determine the age of the manuscripts used more precisely. Wettstein also provides plenty of parallels from profane authors, church writers and from rabbinical literature, but he did not take up Bengel's text-critical rules.

The breakthrough in the 19th century

In the 19th century research took off, numerous new text witnesses were made available for research, and the Textus Receptus was increasingly questioned. Johann Jakob Griesbach introduced many documents from the Church Fathers and old translations and thus broadened the text basis. He combined the inspiration of his teacher Johann Salomo Semler with the knowledge of Bengels and Wettstein. He was the first to leave the previously printed editions as a basis for the text and thus the Textus Receptus in some places in about 200 years. From 1804–1807 he printed in an impressive four-volume folio edition for the first time the text that he believed to be correct on the basis of the results of text-critical science. For the first time he distinguished between an "occidental" (western), Alexandrian and Byzantine review.

Konstantin von Tischendorf published the text of some important manuscripts in print and made them accessible to research. He was able to decipher the Palimpsest Codex Ephraemi and publish the text. On his travels to the libraries and monasteries of Europe and the Orient, he collated many previously unknown or neglected old manuscripts. In 1844 he discovered one of the most important text witnesses of all, the Codex Sinaiticus . In 1862 he published a magnificent and valuable facsimile of the Sinaiticus, for which he specially developed a font that was based on the typeface of the handwriting. The facsimile reproduced the proportions of the letters, the division of the pages, columns and lines and the corrections as far as technically possible at the time from the original. Tischendorf brought out several text-critical editions in which he broke away from the Textus Receptus. He used the readings of the Codex Sinaiticus the first Sigel א(Aleph). Critics complained that he too often gave preference to his newly discovered text witnesses in exuberance. His last work was continued and published by Caspar René Gregory.

Tischendorf wanted to publish the Codex Vaticanus (manuscript B) , which had been known for a long time, but the text was hardly accessible, as well as the Codex Sinaiticus as a facsimile, but received no approval for this. A little later, from 1868 to 1872, by order of the Pope, the Vatican published the text itself in five folio volumes and in 1881 the commentary volume. After many years in which the researchers' access was restricted, its readings were finally generally and reliably known and verifiable. The Codex Alexandrinus was published as a photographic reproduction from 1879 to 1883 . This made the five most important text witnesses available in full, the Codices Sinaiticusא, Alexandrinus (A), Vaticanus (B), Ephraemi (C) and Bezae (D). These five are at the same time the most important main representatives of the three types of text.

Brooke Foss Westcott and Fenton John Anthony Hort published the text edition The New Testament in the Original Greek in 1881 , mostly referred to as Westcott and Hort after the editors . It is largely based on the text of the Codex Sinaiticus and the Codex Vaticanus and is considered to be a solid and reliable edition with a high-quality text even by today's standards. It is still available in bookshops and has formed the basis of many modern translations and revisions.

The Westcott and Hort edition, with its preference for the Alexandrian text type, meant that the English King James Bible was revised and placed on a new and in some cases shorter textual basis. A commission of over 50 scholars set to work and published the New Testament in 1881 and the Revised Version of the Old Testament in 1885 . This has been viewed by many Bible readers as a mutilation of the ancient Bible. There was resistance to the Alexandrian text and the work of Westcott and Hort, especially in the Anglo-Saxon-speaking area. Violent attacks followed by the advocates of the Textus Receptus and the widespread Byzantine text type, also known as majority text. Above all, John William Burgon went so far as to call the Codex Sinaiticus and the Codex Vaticanus false witnesses. There is still the King James Only movement today, which accepts the old King James as the sole Bible. This did not stop the predominance of the Alexandrian text type in text editions, Bible translations and Bible revisions of the 20th and 21st centuries. With the editions of Tischendorf and Westcott and Hort, the Textus Receptus was finally replaced as the basis for critical text editions at the end of the 19th century. This is also evident from the fact that in 1904 the British and Foreign Bible Society gave up printing the Textus Receptus and took over the text of the third edition from Eberhard Nestle for the simple and inexpensive manual editions. The Byzantine text type is still the official text of the Greek Orthodox Church. There are also movements outside the Orthodox churches that prefer the Byzantine text type and want to make it mandatory for translations. The old German-language translations from the Reformation period were gradually adapted to the new text basis in various revisions at the beginning of the 20th century.

Advances in the 20th Century

From 1902 to 1910 Hermann von Soden published The Writings of the New Testament in its oldest accessible text form in four volumes . He dealt intensively with the manuscripts of the majority text of the Byzantine text type, which make up over 80% of the minuscules, and described several text families in them.

Von Soden tried a new cataloging of biblical manuscripts for the growing number of text witnesses , but his system could not finally solve the problems. Shortly before the turn of the 20th century, the first of a series of very old papyrus fragments appeared, such as the Oxyrhynchus papyri , which gave new insights into the early form of the text and which required appropriate treatment in textual criticism.

Tischendorf's search and investigation of the text witnesses was continued by Caspar René Gregory . In 1900 he published The New Testament Text Criticism , in which he describes every available text witness. After personally writing to many scholars in the field of textual criticism and gaining broad approval from scholars of high standing in textual criticism, he published The Greek Manuscripts of the New Testament in 1908 , essentially a list that he used to number the textual witnesses gave a new foundation that is still valid today.

Now all papyrus fragments are numbered consecutively with 1 , 2 , etc. The capitals are designated as usual with Latin and Greek capital letters, but are also numbered with consecutive numbers with a leading zero. There are more capitals than letters in both alphabets, so from a certain point onwards the counting continues without letters, only with numbers with a leading zero. So the numbering isא= 01, A = 02, B = 03 etc. The minuscules are numbered consecutively with Arabic numerals without a preceding 0. Lectionaries are marked with a preceding ℓ: ℓ1, ℓ2, etc. Newly discovered manuscripts come at the end with a new number. If several previously isolated fragments can be assigned to a manuscript, the numbers that become free are not reassigned. Thus it is immediately and clearly clear to every researcher today which handwriting is marked with a certain number, he no longer has to deal with the different counting methods of the different editions and text editions. Gregory's list was later edited and expanded by Kurt Aland and new findings were incorporated, so today it is numbered after Gregory-Aland. New text witnesses are assigned a number in the Institute for New Testament Text Research in Münster today.

In 1898, Eberhard Nestle published the first edition of the Novum Testamentum Graece , which gave several readings from various text editions including the sources. The Nestle , as the edition is called, used Gregory's new system in later editions. His son Erwin Nestle continued the work, he invented the text-critical signs typical for this edition, with which on the one hand a lot of information can be displayed in a small space, while on the other hand the reader needs to practice using it. Since 1952 with the 21st edition, Kurt Aland , later also Barbara Aland, was involved in the editions, so these editions have been briefly referred to as Nestle-Aland since then . Kurt Aland founded the Institute for New Testament Text Research in 1959 , which was later headed by Barbara Aland. He broke away from the earlier printed editions and collations of the previous scientists, which were inaccurate and out of date in many details, and started from scratch. He took his readings directly from the text witnesses, which he checked, photographed and recollated step by step, before including them in the output. In 1981 the two Alands proposed dividing the text witnesses into five categories of New Testament manuscripts . The overall quality of the text is assessed, which is a valuable aid in weighting the readings.

The state of research at the beginning of the 21st century

The fourth edition of the Greek New Testament has the same text as the Nestle-Aland in the 26th and 27th editions, but has a different text-critical apparatus. The current 28th edition of Nestle-Aland is the latest text edition and dominates the scientific field with an extensive text-critical apparatus. The text corresponds to the 5th edition of the Greek New Testament, which is designed more for the translator.

Since the end of the 20th and into the 21st century, the thousands of manuscripts have been increasingly digitized and compared with the help of IT. New technology such as infrared and UV photography improved the legibility of palimpsests and faded manuscripts. Textual criticism in its detailed work is increasingly carried out in scientific institutes such as the Institute for New Testament Text Research and in international and interdenominational bodies and groups. No longer the opinion of individual researchers, however competent, but the consensus of the experts is decisive for the inclusion of a reading in the text output.

Research is currently still working on the complete digitization of the manuscripts and a complete edition with all readings of all known manuscripts. The Editio Critica Maior will probably only come out completely in digitally accessible form. With further advances in IT and the evaluation programs, research hopes to gain further knowledge about the text history of the manuscripts and their relationships with one another. The coherence-based genealogical method, which is only possible with computer-aided methods, is new. The attempt is made to use the similarities and differences between manuscripts to create a genealogical sequence of manuscripts that does justice to the phenomenon of contamination. On the basis of such features, an attempt is made to identify the different templates of a manuscript and to create an approximately complete genealogy. The next step is to evaluate the quotations from the Church Fathers and other early authors more intensively and to focus more on the early translations. There are comparable digitization projects and large-scale text-critical projects for the manuscripts of the Vetus Latina , the Vulgate and the Septuagint .

See also

Notes and individual references

- ↑ cf. for example, Article X of the Chicago Declaration on the Infallibility of the Bible

- ↑ The pastoral letters are among the most recent writings ; researchers usually date them to the end of the first or the beginning of the second century. Also Jude and 2 Peter is dated to the first third of the 2nd century. H. Conzelmann, A. Lindemann, workbook z. NT, 10 ed. Pp. 279 + pp. 357-358.

- ↑ The early translations into Latin, Syriac and the Coptic dialects are relevant. The translations into Armenian, Georgian, Gothic, Ethiopian and Church Slavonic, on the other hand, are less important. Before the beginning of the 20th century with the papyrus finds, there were no Greek text witnesses from the first centuries that reached down to the time of translations. The translations have therefore lost their earlier meaning for textual criticism.

- ↑ Conjectures, another term for "free guessing", a bit more pointed in the professional world, are a stopgap measure if there is a gap in the tradition, the text has obviously been changed afterwards for ideological reasons or if the traditional text is so corrupted that it is no longer makes any recognizable sense. For the New Testament there are only very few isolated cases where this could apply, such as B. at the Comma Johanneum . Today, honesty demands that conjectures be marked in print editions and in translation.

- ↑ Friedrich Blass: On the necessity and value of the textual criticism of the New Testament. Barmen, 1901 p. 13.

- ^ Nestle, Introduction , pp. 8 + 9.

- ^ Hug, Johann L. Introduction to the Writings of the New Testament (First Part) 1847, page 285f digitized

- ^ Hug, Johann L. Introduction to the Writings of the New Testament (First Part) 1847 page: 288 digitized

- ↑ At the time of Tischendorf, the Latin and Greek capital letters of the alphabet for designating the majuscule manuscripts were already in use and there were no longer any letters available for designating the Sinaiticus. The Hebrew letter Alephאshould remedy this and of course make it clear that this handwriting is one of the very best. Tischendorf therefore placed them in front of the previously known capital letters. The sealא has since been retained in textual criticism and the ranking has not been changed.

- ^ John William Burgon, The revision revised , three articles reprinted from the Quarterly review: I. The new Greek text. II. The new English version. III. Westcott and Hort's new textual theory: to which is added a reply to Bishop Ellicott's pamphlet in defense of the revisers and their Greek text of the New Testament, including a vindication of the traditional reading of 1 Timothy III. 16 by John William Burgon. P. 259 and several times in other places.

- ↑ One problem was that the number of text witnesses was now higher than the number of letters in the Latin and Greek alphabet. The use of Hebrew letters would not have been sufficient to denote all text witnesses, and not every printing company had suitable letters available. Another problem was that different manuscripts could be identified with the same seal in different books. In the Gospels, for example, the seal D denoted the Codex Bezae = 05, but in the Pauline letters, D denoted the Codex Claromontanus = 06. The sign H even designates three different manuscripts and is typographically indistinguishable from the Greek capital letter Eta (Η = η).

- ^ Caspar René Gregory : The text criticism of the New Testament , Leipzig 1900

literature

Text output

- Complutensic polyglot by Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros as PDF download of 160 + 328 MB.

- The New Testament in the original Greek , the text revised by Brooke Foss Westcott and Fenton John Anthony Hort , Cambridge and London 1881.

- The New Testament in the original Greek , the text revised by Brooke Foss Westcott and Fenton John Anthony Hort , bilingual American edition with a corresponding English translation and a foreword by Philip Schaff, New York 1882.

- Novum Testamentum Graece . Ed. V. Barbara Aland / Eberhard Nestle u. a., 27th edition Stuttgart 2001 (the current edition is important for text criticism because it includes the latest manuscript finds ) ISBN 3-920609-32-8

- The Greek New Testament . Ed. V. Barbara Aland. Stuttgart 1993 (text of GNT4 is the same as NA27, but the text-critical apparatus is different) ISBN 3-438-05110-9

- Bruce M. Metzger : A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament. A Companion Volume to the United Bible Societies' Greek New Testament (Fourth Revised Edition) . German Bibelges./United Bible Soc., Stuttgart 2nd edition 1994 ISBN 3-438-06010-8

- Novum Testamentum Graecum Editio Critica Maior . Edited by the Institute for New Testament Text Research, Münster. So far published: Vol. 4: The Catholic Letters . Stuttgart 1997-2003

Introductions and resources

- Kurt Aland , Barbara Aland : The Text of the New Testament. Introduction to the scientific editions as well as the theory and practice of modern textual criticism . 1982. Stuttgart 2nd edition 1989 ( the standard work on the subject) ISBN 3-438-06011-6

- Kurt Aland: Concise List of the Greek Manuscripts of the New Testament . ANTT 1. Berlin 2nd edition 1994

- Caspar René Gregory : The textual criticism of the New Testament , Leipzig 1900

- Caspar René Gregory : The textual criticism of the New Testament , Bd. 2 Leipzig 1902

- Caspar René Gregory : The Greek Manuscripts of the New Testament , Leipzig 1908

- Bruce M. Metzger : The Text of the New Testament. Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration . New York 3rd edition 1992 (cf. the outdated German edition: The text of the New Testament. An introduction to the New Testament textual criticism . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1966)

- Eberhard Nestle : Introduction to the Greek New Testament , 3rd revised. Ed., Göttingen 1909.

- James Keith Elliot: A Bibliography of Greek New Testament Manuscripts . MSSNTS 109. Univ. Press, Cambridge 2nd ed. 2000 ISBN 0-521-77012-2

History of New Testament Textual Criticism

- Martin Heide: The only true Bible text? Erasmus of Rotterdam and the question of the original text . 5th, improved and enlarged edition. Publishing house for theology and religious studies, Nuremberg 2006 ISBN 978-3-933372-86-4

- Winfried Ziegler: The “true strict historical criticism”. Life and work of Carl Lachmann and his contribution to New Testament science . Theos 41. Kovač, Hamburg 2000 ISBN 3-8300-0141-X

Current state of research

- Bart D. Ehrman , MW Holmes (Ed.): The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research. Essays on the 'Status Quaestionis'. A Volume in Honor of Bruce M. Metzger . Studies and Documents 46. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids 1995 ISBN 0-8028-2440-4 ; Second edition. Brill, Leiden 2014, ISBN 9789004258402 .

- Kent D. Clarke: Textual Optimism. A Critique of the United Bible Societies' Greek New Testament . JSNTSup 138. Academic Press, Sheffield 1997 ISBN 1-85075-649-X

- A. Denaux (Ed.): New Testament Textual Criticism and Exegesis. Festschrift J. Delobel . BEThL 161. University Press, Peeters, Leuven 2002 ISBN 90-429-1085-2

- Sylvia Nielsen: Euseb of Caesarea and the New Testament. Methods and criteria for the use of Church Fathers' quotations within New Testament textual research . Theory and Research 786. Theology 43. Roderer, Regensburg 2003 ISBN 3-89783-364-6

- Eldon Jay Epp: Perspectives on New Testament Textual Criticism. Collected essays. 1962-2004 . Supplements to Novum Testamentum 116. Brill, Leiden u. a. 2005 ISBN 90-04-14246-0

- Bart D. Ehrman : Studies in the Textual Criticism of the New Testament . New Testament Tools and Studies 33. Brill, Leiden u. a. 2006 ISBN 90-04-15032-3

Web links

- Institute for New Testament Text Research, University of Münster

- New Testament Transcripts (prototype) Interactive surface with the variants of the most important manuscripts

- The Greek New Testament (with variants)

- Text-critical commentary on the four Gospels Extensive application of the text-critical principles to over 1200 variants of the Gospels

- Codex Vaticanus B / 03 Detailed description of the Codex Vaticanus with many pictures (as an example of an important manuscript).

- Greek NT Papyri Complete list of all New Testament papyri.

- Link list for text criticism

- Introduction to the textual criticism of the New Testament ( Memento from June 30, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Article by Ulrich Victor (PDF file; 823 kB)

- Article “Different readings” in the Bible lexicon of bibelkommentare.de

- Nestle-Aland and other editions of the Greek New Testament Listing of all editions currently available.