Vuk Karadžić

Vuk Karadžić ([ ʋûːk stefǎːnoʋitɕ kâradʒitɕ ]; Serbian - Cyrillic Вук Стефановић Караџић ; born October 26 . Jul / 6. November 1787 greg. In Tršić near the Drina , Ottoman Empire ; † 7. February 1864 in Vienna ) was a Serbian Philologist , most important language reformer of the Serbian written language , ethnologist , poet , translator and diplomat .

Life

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić comes from a family in Herzegovina from the Drobnjak tribe. Around 1739 they moved to Jadar and from there on October 26th, 1787 to Serbia, to the village Tršić, in the Loznica district. His parents were Stefan and Jegde, née Zrnić. He got the name Vuk (in German wolf) from his parents, since all male children of his parents had died by then. This should help against the witches (according to an old superstition). Since it was not customary to have a family name in his homeland at that time, his first and father names were initially only Vuk Stefanović (= Wolf, Stefan's son). That is why one finds the name Wolf Stefansohn now and then in older literature. Only "later did he take on the name Karadžić (in the most varied of spellings: Karadzic, Karadschitsch, Karacic, Karadzitsch, Karagich, Karajich) after the place where his parents owned an estate and soon made himself more distinguished under the same name in the scientific world Way known ".

Although there was a lack of educational resources in his place of birth, his strong will to learn overcame all obstacles: he learned to read from a Church Slavonic Bible while herding animals, he carved feathers out of reeds and he made ink out of gunpowder (another source calls dissolved oil soot). He collected the songs, proverbs and stories that were passed down orally in his time.

After Karadžić had participated in the First Serbian Uprising against the Ottoman Empire in 1804, after its suppression he went to Sremski Karlovci (Karlowitz) in Austria and attended the school there, where he learned Latin and German . Thereupon he took part in the second uprising against the Ottomans as secretary of the Serbian leader Nenadović , was secret secretary of the Senate in Belgrade and entrusted with important political missions. When the Ottomans regained control in 1813 and the leader of the Karađorđe uprising had to flee to Austria, Karadžić went to Vienna towards the end of the year .

Here he was persuaded by the Slavist Jernej Kopitar , who recognized his excellent talent for understanding folk art and language, to devote himself exclusively to literary work. The Serbian books available at the time were written in the Slavic Serbian language and were very difficult to understand for the common people. Karadžić's endeavor was therefore to replace the Church Slavonic with the pure vernacular of the Serbs with simple and understandable orthography and to make it a written language. Working tirelessly for this purpose, he published numerous linguistic works, including on folk songs and Serbian grammar, and wrote an extensive dictionary (according to his motto: Write as you speak! ). He also edited the Almanach Danica (Morgenstern), Vienna 1826–34, and the Srpske narodne poslovice (Serbian folk sayings ) for Serbian history and philology . He collected Serbian folk tales and songs and made the Serbian people, largely unknown in Western Europe at the time, known in Germany and the world. His most important work is his translation of the New Testament into the Serbian vernacular in accordance with his language and written reforms, this translation is still in use in the Serbian Orthodox Church today . He was friends and acquainted with many great German intellectuals - such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , of whom there is a fragment of a letter dated December 20, 1823 to Karadžić with the text ... by sending a literal translation of extremely beautiful Serbian songs a lot of joy ... with Jacob Grimm , Leopold Ranke or Johann Gottfried Herder .

In 1828 Karadžić was commissioned by Prince Miloš Obrenović , the ruler of the now autonomous Serbia , to draw up a code of law, which is why he moved to Belgrade. But he could not endure the despotic nature of the prince in the long run and returned to Vienna after two years. In 1834/35 he traveled to Dalmatia and Montenegro , which he reported in the book Montenegro and the Montenegrins . In 1837/1838 he toured Hungary and Croatia , later Serbia repeatedly. He was made an honorary member of the Academies of Science in Vienna, Berlin , Saint Petersburg , Moscow and others.

In 1850, with the so-called Vienna Agreement , some Croatian linguists agreed that the štokavian - Ijekavian dialect should be the basis of the common written language of the Serbs and Croats and that the orthographies of Serbian and Croatian in Latin and Cyrillic should be adapted to one another should be able to transliterate directly from one into the other. The “Agreement” as such, however, had no binding effect, since it was only signed by private individuals and no ratification by state institutions took place.

Vuk Karadžić was with the Austrian Anna, geb. Kraus, married, he had 13 children with her. His daughter Wilhelmina (known as Mina Karadžić (1828–1894)) was a close colleague of her father and published, among other things, the German translation of the collection of Serbian folk tales in 1854, she later became a sought-after painter.

Vuk Karadžić died in Vienna in 1864 and was buried in the Sankt Marxer Friedhof . In 1897 his remains were transferred to Belgrade and buried there in the historic cathedral in the city center opposite the grave of the Serbian enlightener Dositej Obradović .

Linguistic nationalism and the Greater Serbian idea

During the nation-building phase in the Western Balkans in the first half of the 19th century, Karadžić was of the opinion that all Slavs who speak a štokavian dialect speak the Serbian language and are therefore Serbs. According to this definition, he declared most of the Roman Catholic Croats as well as all Muslim Bosniaks to be Serbs who were just unaware of it. However, he later wrote that he was giving up this definition because he saw that the Croatians of his time did not agree with this definition, and he switched to the definition of the Serbian nation based on Orthodoxy and the Croatian nation based on Catholicism.

Before that, he wrote in the chapter Srbi svi i svuda (Serbs all and everywhere) of his work Kovčežić za istoriju, jezik i običaje Srba sva tri zakona , written in 1836 and published in 1849 (A suitcase full of the history, linguistics and folk customs of the Serbs of all three denominations):

“It is reliably known that the Serbs are currently in Serbia [...], in Metochia , in Bosnia , in Herzegovina , in the Zeta , in Montenegro , in the Banat , in the Batschka , in Syrmia , in the right Danube region of Osijek to Szentendre , in Slavonia , in Croatia […], in Dalmatia and in the entire Adriatic coast almost from Trieste to the Buna . [...] It is not yet reliably known how far the Serbs reach in Albania and Macedonia [...] In the countries mentioned there will be at least five million inhabitants who all speak the same language, but who are divided into three categories according to religion three million are Greek [...] of the remaining two million, two thirds are Turkish (in Bosnia, Herzegovina and Zeta) and about one third are Roman . [...] It is surprising that the Serbs of the Catholic faith do not want to call themselves Serbs. […] It is only difficult for those Serbs of the Roman faith to call themselves Serbs, but they will gradually get used to it, because if they don't want to be Serbs, then they have no national name at all. […] In no way can I understand how those of our brothers of the Roman faith could use this name (the Croatian one), for example in the Banat, in the Batschka, in Syrmia, in Slavonia, in Bosnia and Herzegovina and in Dubrovnik live and speak the same language as the Serbs. Those of the Turkish faith cannot yet be asked to think about this ethnic origin, but as soon as schools are set up among them [...] they will immediately find out and recognize that they are not Turks but Serbs. "

Accordingly, he also collected his Serbian folk songs from the Croats and Bosniaks. Serb nationalists also rely on Karadžić's theses to justify their Greater Serbian goals. Most recently in the Croatian and Bosnian wars , above all Radovan Karadžić , who declared himself a descendant of Vuk Karadžić in accordance with propaganda and had himself filmed in front of his picture.

Works

Vuk Stefanović Karadžić was the most important representative of the Serbian language reform of the 19th century. Most of his works in Serbian are related to this. As early as the end of the 18th century, efforts were made to create a written language based on a vernacular that the people could understand. The monk, preacher and writer Gavrilo Stefanović Venclović first translated the Holy Scriptures into a Serbian vernacular around 1740 . However, this Bible was banned by the Serbian Orthodox church hierarchy, but later served in many ways as a model for the translation of the New Testament by Karadžić. During the Serbian uprisings against the Ottoman Empire, the call for a separate Serbian written language became louder and louder. This was opposed by the so-called Slavic Circle around the Orthodox Church hierarchy, which vehemently defended Church Slavonic as the common written language of all Orthodox Slavic peoples. Karadžić also found his most bitter opponents in the Slavic Circle. He was severely attacked and hostile, but his views prevailed. Karadžić's reforms were finally recognized in 1860 as pointing the way for the written Serbian language.

Works in Serbian

- Mala prostonarodna slavenoserbska pjesnarica . Vienna 1814. A collection of Serbian folk songs.

- Pismenica srpskoga jezika . Vienna 1814. The first Serbian grammar that Jacob Grimm translated into German.

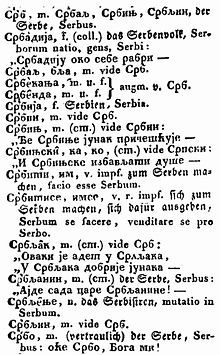

- Srpski rječnik . Vienna 1818 and 2nd increased edition. Vienna 1852. Serbian dictionary with Latin and German translation of the words and many ethnological and historical explanations.

- Narodne srpske pjesme . Four volumes. Leipzig and Vienna 1823–33 and 2nd extended edition, Vienna 1841. This exemplary collection of Serbian folk songs attracted the most attention of all of his works, including abroad.

- Kovčežić za istoriju, jezik i običaje Srba sva tri zakona . Print shop of the Armenian monastery, Vienna 1849.

- Srpske pjesme iz Hercegovine . Vienna 1866. A collection of Serbian folk songs from Herzegovina, translated into many languages.

- Crven ban: narodna erotska poezija . A collection of erotic Serbian folk poetry that has long been kept secret because of its suggestive content.

It is also important to mention his translation of the New Testament ( Novi zavjet ) into the Serbian vernacular (Vienna 1847).

Works in German translation

- Short Serbian grammar . Translated and with a preface by Jacob Grimm. Reprint of the Leipzig a. Berlin, Reimer, 1824. New ed. u. introduced by Miljan Mojasević and Peter Rehder. Sagner, Munich 1974, ISBN 3-87690-086-7 .

- Folk songs of the Serbs . Metrically translated and historically introduced by Talvj . Run 1st hall 1825.

- Folk songs of the Serbs . Metrically translated and historically introduced by Talvj. 2nd rev. Edition. 2nd hall 1835.

- Folk songs of the Serbs . Metrically translated and historically introduced by Talvj. New revised and increased edition. T. 1. Leipzig 1853.

- Serbian folk songs . From the Serbian. Parts of a historical collection. Collected and edited. by Vuk Stefanović Karadžić. Translated by Talvj. Selected and provided with an afterword by Friedhilde Krause. Reclam, Leipzig 1980.

- Folk tales of the Serbs. Collected and edited. by Wuk Stephanowitsch Karadschitsch. Translated into German by his daughter Wilhelmine. With a preface by Jacob Grimm. In addition to an appendix of more than 1,000 Serbian proverbs. G. Reimer, Berlin 1854 ( digitized from Google Books).

- Montenegro and the Montenegrins: A Contribution to Knowledge of European Turkey and the Serbian People. Publishing house of JG Cotta'schen Buchhandlung, Stuttgart and Tübingen 1837 ( digitized from Google Books)

Works in the holdings of the Berlin State Library - Prussian Cultural Heritage

- Zivomir Mladenović: Neobjavljene pesme Vuka Karadžića . Cigoja Stampa, Beograd 2004.

- Vuk Stefanović Karadžić: Izbor iz dela . Izdavačka Kuća "Draganić", Beograd 1998.

- Miloslav Samardžić: Tajne "Vukove reforme". 2nd Edition. Pogledi, Kragujevac 1997.

- PA Dmitriev: Serbija i Rossija: stranicy istorii kul'turnych i naucnych vzaimosvjazej . Petropolis, Sankt-Peterburg 1997.

- Claudia Hopf: Language nationalism in Serbia and Greece: Theoretical foundations as well as a comparison of Vuk Stefanović Karadzić and Adamantios Korais . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1997.

- Miljan Mojasević: Jacob Grimm and Serbian Literature and Culture . Hitzeroth, Marburg 1990.

- Wilfried Potthoff: Vuk Karadzić in a European context . Contribution to the international scientific symposium of the Vuk Karadzić-Jacob Grimm Society on November 19 and 20, 1987 in Frankfurt am Main. Winter, Heidelberg 1990.

- Vladimir Stojancević: Vuk Karadzić i njegovo doba: rasprave i clanci . - Zavod za Udzbenike i Nastavna Sredstva et al., Beograd 1988.

- Zivomir Mladenović: Vuk Karadzić i Matica srpska . Izd. Ustanova Nauc. Delo, Beograd 1965.

- Vuk Stefanović Karadžić: Vukovi zapisi . Kultura, Beograd 1964.

See also

literature

- Constantin von Wurzbach : Karadschitsch, Wuk Stephanowitsch . In: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich . 10th part. Kaiserlich-Königliche Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1863, pp. 464–467 ( digitized version ).

- Vera Bojić: Jacob Grimm and Vuk Karadžić: A comparison of their language perceptions and their collaboration in the field of Serbian grammar . Sagner, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-87690-127-8 .

- Wolf Dietrich Behschnitt: Vuk Stefanović Karadžić: "Srbi svi i svuda". In: Nationalism among Serbs and Croats 1830–1914: Analysis and typology of national ideology. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 1980, ISBN 3-486-49831-2 , pp. 65-82.

- Claudia Hopf: Linguistic nationalism in Serbia and Greece: Theoretical foundations and a comparison of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić and Adamantios Korais . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1997, ISBN 3-447-03953-1 .

- Reinhard Lauer (Ed.): Language, literature, folklore with Vuk Stefanović Karadžić . Contribution to an international symposium, Göttingen, February 8-13, 1987. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 1988, ISBN 3-447-02848-3 .

- Wolfgang Eschker (eds.): Jacob Grimm and Vuk Karadžić: Testimonies of a scholarly friendship . Röth Verlag, Kassel 1988, ISBN 3-87680-352-7 . Text in German and Serbo-Croatian.

- Wilfried Potthoff (Ed.): Vuk Karadžić in a European context . Contribution to the international scientific symposium of the Vuk-Karadžić-Jacob-Grimm Society on November 19 and 20, 1987, Frankfurt am Main. C. Winter Verlag, Heidelberg 1990, ISBN 3-533-04281-2 .

Web links

- Karadschitsch, Wuk Stephanowitsch , in Constantin von Wurzbach Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich , 10th volume, Vienna 1863.

- Digital edition of folk songs by the Serbs of Talvj, Leipzig 1853

- Digital edition Small Serbian grammar by Vuk Karadžić, into German by Jacob Grimm, Leipzig and Berlin 1824

- Literature by and about Vuk Karadžić in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Vuk Karadžić in the German Digital Library

- Vuk Karadžić portal of the Rastko project ( en )

Individual evidence

- ^ BLKÖ: Karadschitsch, Wuk Stephanowitsch - Wikisource. Retrieved September 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Ernst Kilian: The rebirth of Croatia from the spirit of language . In: Neven Budak u. a. (Ed.): Croatia: Regional studies - history - culture - politics - economy - law . Vienna u. a. 1995, ISBN 978-3-205-98496-2 , pp. 380 .

- ↑ Vuk Karadžić: Kovčežić za istoriju, jezik i običaje Srba sva tri zakona . Print shop of the Armenian monastery, Vienna 1849, pp. 1–27.

- ↑ Ivan Čolović: The renewal of the past. Time and Space in Contemporary Political Mythology. In: Nenad Stefanov / Michael Werz: Bosnia and Europe: The ethnicization of society . Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 1994, ISBN 3-596-12554-5 , p. 94 f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Karadžić, Vuk Stefanović |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Караџић, Вук Стефановић |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Serbian philologist and creator of the modern written Serbian language |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 6, 1787 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Tršić on the Drina |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 7, 1864 |

| Place of death | Vienna |