Champagne: Difference between revisions

→Serving Champagne: temperature in °C |

|||

| Line 179: | Line 179: | ||

*[http://www.libation-unlimited.com/champagne.aspx Champagne reviews and tasting notes] from ''Libation U.N. Limited'' |

*[http://www.libation-unlimited.com/champagne.aspx Champagne reviews and tasting notes] from ''Libation U.N. Limited'' |

||

*[http://www.maisons-champagne.com/traduction/english/index_gb.php Grand Marques and Houses] Official site of the Union of Champagne Houses |

*[http://www.maisons-champagne.com/traduction/english/index_gb.php Grand Marques and Houses] Official site of the Union of Champagne Houses |

||

* [http://www.toastmaster.gb.com/sabrage.html ''What is Sabrage?''] |

|||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

Revision as of 05:56, 13 November 2006

Champagne is a sparkling wine produced by inducing the in-bottle secondary fermentation of wine to effect carbonation. It is named after the Champagne region of France. While the term "champagne" is often used by makers of sparkling wine in other parts of the world, many claim it should properly be used to refer only to the wines made in the Champagne region.

Origins

Wines from the Champagne region were already known before medieval times. Churches owned vineyards, and monks produced wine for use in the sacrament of Eucharist. French kings were traditionally anointed in Reims. Champagne wine flowed as part of coronation festivities.

Kings appreciated the still, light, and crisp wine, and offered it as an homage to other monarchs in Europe. In the 17th century, still wines of Champagne were the chosen wines for celebration in European countries. English people were the biggest consumers of Champagne wines, and drank a lot of sparkling wines.

The first commercial sparkling wine was produced in the Limoux area of Languedoc about 1535. They did not invent it; nobody knows who first made it, although the British make a reasonably good claim. Contrary to legend and popular belief, the French monk Dom Perignon did not invent champagne, although it is almost certainly true that he developed many advances in the production of this beverage. Some people believe that champagne was created quite by accident, but no one has been able to prove that this is the case. Some others believe that the first champagne was made with rhubarb but was changed due to the high cost.

Somewhere in the end of the 17th century, the sparkling method was imported to the Champagne region, associated with specific procedures for production (including smooth pressing and dosage), and stronger bottles (invented in England) that could hold the added pressure. Around 1700, sparkling Champagne was born.

"The leading manufacturers devoted considerable energy to creating a history and identity for their wine, associating it and themselves with nobility and royalty. Through advertising and packaging they persuaded the world to turn to champagne for festivities and rites de passage and to enjoy it as a luxury and form of conspicuous consumption. Their efforts coincided with an emerging middle class that was looking for ways to spend its money on symbols of upward mobility."

In 1866, the famous entertainer and star of his day, George Leybourne (who called himself Champagne Charlie) began a career of making celebrity endorsements for Champagne. The Champagne maker Moet commissioned him to write and perform songs extolling the virtues of Champagne, especially as a reflection of taste, affluence, and the good life. He also agreed to drink nothing but Champagne in public. Leybourne was seen as highly sophisticated and his image and efforts did much to establish Champagne as an important element in enhancing social status. It was a marketing triumph the results of which endure to this day.

English people loved the new sparkling wine, and spread it all over the world. Brut Champagne, the modern Champagne, was created for the British in 1876. The Russian royalty also consumed huge quantities, preferring the sweeter styles.

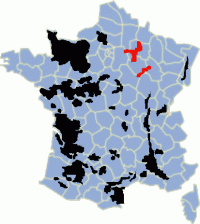

"Champagne" and the law

In Europe and most other countries, the name "Champagne" is legally protected as part of the Treaty of Madrid (1891) to mean only sparkling wine produced in its namesake region and adhering to the standards defined for that name as an Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée. This right was reaffirmed in the Treaty of Versailles following World War I. Even the term méthode champenoise, or champagne method is, as of 2005, forbidden in favor of méthode traditionnelle. There are sparkling wines made all over the world, and many use special terms to define their own sparkling wines: Spain uses Cava, Italy calls it spumante, and South Africa uses Cap Classique. A sparkling wine made from Muscat grapes in Italy uses the DOCG Asti. In Germany, Sekt is a common sparkling wine. Other regions of France are forbidden to use the name Champagne; for example, wine-makers in Burgundy and Alsace produce Crémant. However, some Crémant producers label their product in a manner apparently designed to mislead consumers into believing that they are actually purchasing Champagne.[citation needed]

Other sparkling wines not from Champagne sometimes use the term "sparkling wine" on their label. While most countries have labeling laws which prevent the use of the term Champagne on any wine not from the region, some – including the United States – permit wine producers to use the name “Champagne” as a semi-generic name. One reason U.S. wine producers are allowed to use the European names is that the Treaty of Versailles, though signed by President Wilson, was never ratified by the U.S. Senate. The Treaty of Versailles included a clause designed to limit the German wine industry and to allow the use of the term Champagne only on wines from the Champagne region of France (which had been in the middle of numerous WWI battles). As the U.S. Senate never ratified the Treaty, this language never was implemented in the United States.

Current U.S regulations require that what is defined as a semi-generic name (such as Champagne) shall be used on a wine label only if there appears next to that name the appellation of "the actual place of origin" in order to prevent any possible consumer confusion. Because the quality of their wines are now widely recognized, many US producers of quality sparkling wine no longer find the term "Champagne" useful in marketing. In addition, some key US wine growing areas such as Napa, Oregon and Washington now view semi-generic labeling as harmful to their reputations (see Napa Declaration on Place).

The Champagne winemaking community, under the auspices of the Comité Interprofessionel du Vin de Champagne, has developed a comprehensive set of rules and regulations for all wine that comes from the region in order to protect the economic interests of that community. They include a codification of the most suitable places for grapes to grow; the most suitable types of grapes (most Champagne is produced from one or a blend of up to three varieties of grapes - chardonnay, pinot noir, and meunier - although five other varietals are permitted); and a lengthy set of requirements that specifies most aspects of viticulture. This includes vine pruning, the yield of the vineyard, the degree of pressing applied to the grapes, and the time that bottles must remain on the lees. It can also limit the release of Champagne into the market in order to maintain prices. Only if a wine meets all these requirements may the name Champagne be placed on the bottle. The rules that have been agreed upon by the CIVC are then presented to the INAO for final approval.

Reporter Pierre-Marie Doutrelant revealed that "many famous Champagne houses, when short of stock, bought bottled but unlabeled wine from cooperatives or one of the big private-label producers in the region, then sold it as their own" (Prial).

Production

Grapes used for Champagne are generally picked earlier, when sugar levels are lower and acid levels higher. Except for pink or rosé Champagnes, the juice of harvested grapes is pressed off quickly, to keep the wine white. The traditional method of making Champagne is known as the Méthode Champenoise.

The first fermentation begins in the same way as any wine, converting the natural sugar in the grapes into alcohol while the resultant carbon dioxide is allowed to escape. This produces the "base wine". This wine is not very pleasant by itself, being too acidic. At this point the blend is assembled, using wines from various vineyards, and, in the case of non-vintage Champagne, various years.

The blended wine is put in bottles along with yeast and a small amount of sugar, called the liqueur de tirage, and stored in a wine cellar horizontally, for a second fermentation. During the secondary fermentation the carbon dioxide is trapped in the bottle, keeping it dissolved in the wine. The amount of added sugar will determine the pressure of the bottle. To reach the standard value of 6 bars inside the bottle is necessary to have 18 grams of sugar, and the amount of yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is regulated by the European Commission (Regulation 1622/2000, 24 July 2000) to be 0.3 grams per bottle. The "liqueur de tirage" is then a mixture of sugar, yeast and still champagne wine.

After aging (a minimum from one and a half to three years), they undergo a process known as riddling (remuage in French), in which they are rotated a small amount each day and gradually moved to a neck-down orientation, so that the sediment ('lees') collects in their necks and can be removed. The removal process is called "disgorging" (dégorgement in French), and was a skilled manual process, where the cork and the lees were removed without losing large quantities of the liquid, and a dosage (a varying amount of additional sugar) is added. Until this process was invented (reputedly by Madame Clicquot in 1800) Champagne was cloudy, a style still seen occasionally today under the label méthode ancestrale. Modern disgorgement is automated by freezing a small amount of the liquid in the neck and removing this plug of ice containing the lees. A cork is then inserted with a capsule and wire cage securing it in place.

Wines from Champagne cannot legally be sold until it has aged on the lees in the bottle for at least 15 months. Champagne's AOC regulations require that vintage Champagnes are aged in cellars for three years or more before disgorgement, but most top producers exceed this minimum requirement, holding bottles on the lees for 6 to 8 years before disgorgement.

Even experts disagree about the effects of aging on Champagne after disgorgement. Some prefer the freshness and vitality of young, recently disgorged Champagne, and others prefer the baked apple and caramel flavors that develop from a year or more of aging.

The majority of the Champagne produced is non-vintage (also known as mixed vintage), a blend of wines from several years. Typically the majority of the wine is from the current year but a percentage is made of "reserve wine" from previous years. This serves to smooth out some of the vintage variations caused by the marginal growing climate in Champagne. Most Champagne houses strive for a consistent "house style" from year to year, and this is the hardest task of the winemaker.

The grapes to produce vintage Champagne must be 100% from the year indicated (some other wines in the EU need only be 85% to be called vintage, depending on their type and appellation). To maintain the quality of non-vintage champagne a maximum of half the grapes harvested in one year can be used in the production of vintage Champagne ensuring at least 50%, though usually more, is reserved for non-vintage wines. Vintage Champagnes are the product of a single high-quality year, and bottles from prestigious makers can be rare and expensive.

Champagne's sugar content varies. The sweetest level is doux (meaning sweet), proceeding in order of increasing dryness to demi-sec (half-dry), sec (dry), extra sec (extra dry), brut (almost completely dry), and extra brut / brut nature / brut zero (no additional sugar, sometimes ferociously dry).

Champagne producers

There are over 100 champagne houses and 15,000 smaller vignerons (vine-growing producers) operating in Champagne. These companies manage some 32,000 hectares of vineyards in the region, and employ over 10,000 people.

Annual sales by all producers total over 300 million bottles per year, equating to roughly €4.3 billion of revenue. Roughly two-thirds of these sales are made by the large champagne houses and their grandes marques (major brands). 58% of total production is sold within France, with the remaining 42% being exported around the world – primarily to the U.K., the U.S., and Germany.

At any one time, champagne producers collectively hold a stock of about 1 billion bottles which are being matured, equating to more than three years of sales volume.

The type of champagne producer can be identified from the abbreviations followed by the official number on the bottle:

- NM: Négociant manipulant. These companies (including the majority of the larger brands) buy grapes and make the wine

- CM: Coopérative de manipulation. Co-operatives that make wines from the growers who are members, with all the grapes pooled together

- RM: Récoltant manipulant. A grower that also makes wine from their own grapes

- SR: Société de récoltants. An association of growers making a shared Champagne but who are not a co-operative

- RC: Récoltant coopérateur. A co-operative member selling Champagne produced by the co-operative under its own name

- MA: Marque auxiliaire or Marque d'acheteur. A brand name unrelated to the producer or grower; the name is owned by someone else, for example a supermarket

- ND: Négociant distributeur. A wine merchant selling under his own name

Varieties

Champagne is a single Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée. Grapes must be the white Chardonnay, or the red Pinot Noir or Pinot Meunier (a few very rare other grapes that were historically important are allowed, but very unusual). Champagnes made exclusively from Chardonnay are known as blanc de blancs, and those exclusively from the red grapes as blanc de noirs.

Champagne is typically a white wine even if it is produced with red grapes, because the juice is extracted from the grapes using a gentle process that minimizes the amount of time the juice spends in contact with the skins, which is what gives red wine its colour. Rosé wines are also produced, either by permitting the juice to spend more time with the skins to impart a pink color to the wine, or by adding a small amount of red wine during blending. The amount of sugar (dosage) added after the second fermentation and ageing also varies, from brut zéro or brut natural, where none is added, through brut, extra-dry, sec, demi-sec and doux. The most common is brut, although in the early 20th century Champagne was generally much sweeter.

Most Champagne is non-vintage, produced from a blend of years (the exact blend is only mentioned on the label by a few growers), while that produced from a single vintage is labelled with the year and Millésimé.

Many Champagnes are produced from bought-in grapes by well known brands such as Veuve Clicquot or Mumm.

The Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne

All of the over 15,000 growers, cooperatives and over 300 houses that are central to producing Champagne are members of the Comite Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne (CIVC), established in 1941 under the auspices of the French government (now represented by the Ministry of Agriculture). This organization has a system in which both the houses and the growers are represented at all levels. This includes a co-presidency where a grower representative and a representative of the houses share the running of the organization. This system is designed to ensure that the CIVC's primary mission, to promote and protect Champagne and those who produce it, is done in a manner that represents the interests of all involved. This power structure has played an important role in the success of Champagne worldwide and the integrity of the appellation itself.

The CIVC is charged with organizing and controlling the production, distribution, and promotion of Champagne. Until 1990, it set the price for grapes and still intervenes to regulate the size of the harvest, to decide if any should be withheld from production into Champagne and, if so, the amount to be withheld from the market.

Bubbles

An initial burst of effervescence occurs when the champagne contacts the dry glass on pouring. These bubbles may form on imperfections in the glass that facilitate nucleation. However, after the initial rush, these naturally occurring imperfections are typically too small to consistently act as nucleation points as the surface tension of the liquid smooths out these minute irregularities.

- "Contrary to a generally accepted idea, nucleation sites are not located on irregularities of the glass itself. The length-scale of glass and crystal irregularities is far below the critical radius of curvature required for the non-classical heterogeneous nucleation." G. Liger-Belair et al, (2002) Europhysics News 33 (1)

The nucleation sites that act as a source for the ongoing effervescence are not natural imperfections in the glass, but actually occur either:

- where the glass has been etched by the manufacturer or the customer. This etching is typically done with acid, a laser, or a glass etching tool from a craft shop to provide nucleation sites for continuous bubble formation (note that not all glasses are etched in this way); or, to a lesser extent,

- on cellulose fibres left over from the wiping/drying process as shown by Gérard Liger-Belair, Richard Marchal, and Philippe Jeandel with a high-speed video camera. (See: References)

It is interesting to note that Dom Perignon was originally charged by his superiors at the Abbey of Hautvillers to get rid of the bubbles since the pressure in the bottles caused many of them to explode in the cellar and was thought to be the work of the devil.

It is widely accepted that the smaller the bubbles the better the Champagne.

Champagne bottles

Champagne is mostly fermented in two sizes bottles, standard bottle (750 mL), and Magnum (1.5 L). In general, magnums are thought to be higher quality, as there is less oxygen in the bottle, and the volume to surface area favors the creation of appropriately-sized bubbles. However, there is no hard evidence for this view. Other bottle sizes, named for Biblical figures, are generally filled with Champagne that has been fermented in standard bottles or magnums.

Sizes larger than Jeroboam (3.0 L) are rare. Primat sized bottles (27 L) - and as of 2002 Melchizedek sized bottles (30 L) - are exclusively offered by the House Drappier. The same names are used for bottles containing wine and port; however Jeroboam, Rehoboam and Methuselah refer to different bottle volumes. On occasion unique sizes have been made for special occasions and people, the most notable example perhaps being the 20 fluid ounce / 60 cL. bottle (Imperial pint) made specially for Sir Winston Churchill by Pol Roger. This was served to Mr. Churchill by his butler at 11am as he was getting up.

Opening Champagne bottles

The deliberate spraying of Champagne has become an integral part of some sports trophy presentations, such as the famous podium presentation at the conclusion of a Formula 1 Grand Prix; however, Champagne enthusiasts sometimes cringe at the waste. To reduce the risk of spilling Champagne and/or turning the cork into a projectile, open a Champagne bottle as follows:

- Remove the foil and pull down the wire loop;

- Drape a towel over the bottle:

- Place your hand over the cork;

- Loosen but don't remove the wire cage;

- Grasp the cork and the cage firmly with your hand, then rotate the bottle (rather than the cork) by holding it at the base; this should allow the cork to come out on its own.

The desired effect is to ease the cork out with a sigh or a whisper rather than a pop or to shoot the cork across the room or produce a fountain of foamy wine. Most wine connoisseurs insist that the ideal way to open a bottle of Champagne is to do it so carefully and gently that very little sound is emitted at all.

Sabrage

A sabre can be used to open a Champagne bottle with great ceremony. This technique is called sabrage. The sabre is slid along the body of the bottle toward the neck. The force of the blade hitting the lip separates the lip from the neck of the bottle. The cork and lip remain together after separating from the neck. Sabrage does not involve a slicing motion. To properly execute, one should:

- Select a heavy sabre, with a rather short blade and broad back;

- Hold in one hand the sabre. Use the back and not the cut of the blade;

- Hold in the other hand the Champagne bottle on its lowest part, the wire cage loosened or removed;

- Touch and slide the blade alongside the bottle until it hits the swelling on the bottleneck. The jolt will break the bottle and its tip will fly away in a trajectory;

- Have part of the spray spill out in order to wash away potential glass splinters;

Using the sabre method is not particularly difficult, but some precautions are necessary:

- The sabre is a weapon and might be dangerous;

- The tip of the bottle will fly away with force. Keep the foreseen trajectory free of obstacles;

- Check fluid for glass splinters before drinking;

- Do not touch the top of the bottle after opening; it is likely to have razor sharp edges

Serving Champagne

Champagne is usually served in a champagne flute, whose characteristics include a long stem with a tall, narrow bowl and opening. The wider, flat champagne coupe; which has a saucer-shaped bowl and is commonly associated with Champagne, is no longer preferred by connoisseurs because it does not preserve the bubbles and aroma of the wine as well.

Alternatively, when tasting Champagne, a big red wine glass (i.e. a glass for Bordeaux) can be used, as the aroma spreads better in the larger volume of the glass.

Glasses should not be overfilled: flutes should be filled only to ⅔ of the glass, and big red wine glasses not more than ⅓ of the glass.

Champagne is always served cold, and is best drunk at a temperature of around 7 to 9 °C (43 to 48 °F). Often the bottle is chilled in a bucket of ice and water before and after opening. Champagne buckets are made specifically for this purpose, and often have a larger volume than standard wine-cooling buckets (to accommodate the larger bottle, and more water and ice).

Note: When drinking vintage Champagnes, the goal is to open a cold bottle and serve from a bottle and/or drink from a glass that is warming up to 11 to 15 °C (52 to 60°F) range. (Do not artificially warm it, just let it happen.)

Once a bottle (of good Champagne) is opened there is no reason to put it back in the ice bucket. The primary use of an ice bucket is to get the bottle open without losing bubbles or wine. Once the bottle is open the bucket has served its purpose.

Aging

There is a debate about the aging of champagne. Champagne's freshness have contributed to most people's impression that it should be enjoyed soon after purchase. Vintage champagne that has been released are often put aside to be enjoyed years later. As champagne ages, it deepens in color and often develops bready, caramelized flavors and aromas.

See also

- Champagne Riots

- Coteaux Champenois AOC

- Conspicuous consumption

- List of cocktails

- Rosé des Riceys AOC

- Sparkling wine

- Wine fraud

References

- Template:Fr G. Liger-Belair (2002). "La physique des bulles de champagne". Annales de Physique. 27 (4): 1–106.

- G. Liger-Belair; et al. (2002). "Close-up on Bubble Nucleation in a Glass of Champagne" (PDF). American Society for Enology and Viticulture. 53 (2): 151–153.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) PDF abstract

- G. Liger-Belair; et al. (2002). "Effervescence in a glass of champagne: A bubble story". Europhysics News. 33 (1).

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)

- Guy, Kolleen. When Champagne became French: Wine and the Making of a National Identity. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

- Robinson, Jancis (Ed.) The Oxford Companion to Wine. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, second edition, 1999.

- Prial, Frank J. Decantations. New Yrk: St. Maritin's and grifin Publishers, 2001, p. 24.

External links

- ChampagneMagic.com - Champagne Lovers' website

- Celebrating Champagne

- Official site of the Comité Interprofessionel du Vin de Champagne trade association

- Official site of the Office of Champagne, USA

- Article on champagne from The Wine Lover's Companion

- Champagne reviews and tasting notes from Libation U.N. Limited

- Grand Marques and Houses Official site of the Union of Champagne Houses

Further reading

- Tom Stevenson (2003) World Encyclopedia of Champagne and Sparkling Wine. Wine Appreciation Guild ISBN 1-891267-61-2

- Gérard Liger-Belair (2004) Uncorked: The Science of Champagne. Princeton University Press ISBN 0-691-11919-8