Monetarism: Difference between revisions

ref for monetary rule recognized to be unsuccessful - cites |

I changed the inflation rate for May 1979, using a journal reference for the period. |

||

| (470 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ |

{{Short description|School of thought in monetary economics}} |

||

{{Macroeconomics sidebar}} |

|||

'''Monetarism''' is a school of economic thought concerning the determination of [[measures of national income and output|national income]] and monetary [[economics]]. It focuses on the supply of money in an economy as the primary means by which the rate of inflation is determined. |

|||

{{Capitalism sidebar}} |

|||

[[File:CPI 1914-2022.webp|thumb|alt=CPI 1914-2022|261px| |

|||

Monetarism today is mainly associated with the work of [[Milton Friedman]], who was among the generation of economists to accept [[Keynesian economics]] and then criticize it on its own terms. Friedman and [[Anna Schwartz]] wrote an influential book, ''Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960'', and argued that "[[inflation]] is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon." Friedman advocated a [[central bank]] policy aimed at keeping the supply and demand for money at equilibrium, as measured by growth in productivity and demand. The monetarist argument that the demand for money is a stable function gained considerable support during the late 1960s and 1970s from the work of [[David Laidler]]. The former head of the [[United States Federal Reserve]], [[Alan Greenspan]], is generally regarded as monetarist in his policy orientation. The [[European Central Bank]] officially bases its monetary policy on money supply targets. |

|||

{{legend|#0076BA |[[Inflation]]}} |

|||

{{legend|#EE220C |[[Deflation]]}} |

|||

{{legend-line|#1DB100 solid 3px|[[Money supply|M2 money supply]] increases Year/Year}} |

|||

]] |

|||

'''Monetarism''' is a [[school of thought]] in [[monetary economics]] that emphasizes the role of policy-makers in controlling the amount of [[money in circulation]]. It gained prominence in the 1970s, but was mostly abandoned as a direct guidance to [[monetary policy]] during the following decade because of the rise of inflation targeting through movements of the official interest rate. |

|||

Critics of monetarism include both [[neo-Keynesians]] who argue that demand for money is intrinsic to supply, and some conservative economists who argue that demand for money cannot be predicted. [[Joseph Stiglitz]] has argued that the relationship between inflation and money supply growth is weak when the inflation is low. |

|||

The monetarist theory states that variations in the [[money supply]] have major influences on [[measures of national income and output|national output]] in the short run and on [[price level]]s over longer periods. Monetarists assert that the objectives of [[monetary policy]] are best met by targeting the growth rate of the [[money supply]] rather than by engaging in [[discretionary policy|discretionary monetary policy]].<ref name="Cagan">[[Phillip Cagan]], 1987. "Monetarism", ''[[The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics]]'', v. 3, Reprinted in John Eatwell et al. (1989), ''Money: The New Palgrave'', pp. 195–205, 492–97.</ref> Monetarism is commonly associated with [[neoliberalism]].<ref name="harvey1">{{Cite book|title=A Brief History of Neoliberalism|author-link=David Harvey (geographer)|last=Harvey|first=David|isbn=978-0-19-928326-2|url=https://global.oup.com/academic/product/a-brief-history-of-neoliberalism-9780199283279?cc=us&lang=en&|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|year=2005}}</ref> |

|||

== What is monetarism? == |

|||

Monetarism is mainly associated with the work of [[Milton Friedman]], who was an influential opponent of [[Keynesian economics]], criticising Keynes's theory of fighting economic downturns using [[fiscal policy]] ([[government spending]]). Friedman and [[Anna Schwartz]] wrote an influential book, ''[[A Monetary History of the United States|A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960]]'', and argued "that [[inflation]] is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon".<ref>{{Cite book|title=Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960.|first=Milton|last=Friedman|date=2008|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-0691003542|oclc=994352014}}</ref> |

|||

Monetarism is an economic theory which focuses on the [[macroeconomics|macroeconomic]] effects of the supply of money and central banking. Formulated by [[Milton Friedman]], it argues that excessive expansion of the money supply is inherently [[inflation]]ary, and that monetary authorities should focus solely on maintaining price stability. |

|||

Though Friedman opposed the existence of the [[Federal Reserve System|Federal Reserve]],<ref name="reason">{{cite web |first=Brian|last=Doherty|date=June 1995|title=Best of Both Worlds|url=http://reason.com/archives/1995/06/01/best-of-both-worlds|publisher=Reason|access-date=July 28, 2010}}</ref> he advocated, given its existence, a [[central bank]] policy aimed at keeping the growth of the money supply at a rate commensurate with the growth in productivity and [[aggregate demand|demand for goods]]. Money growth targeting was mostly abandoned by the central banks who tried it, however. Contrary to monetarist thinking, the relation between money growth and inflation proved to be far from tight. Instead, starting in the early 1990s, most major central banks turned to direct [[inflation targeting]], relying on steering short-run [[interest rate]]s as their main policy instrument.<ref name=Blanchard/>{{rp|483-485}} Afterwards, monetarism was subsumed into the [[new neoclassical synthesis]] which appeared in macroeconomics around 2000. |

|||

This theory draws its roots from two almost diametrically opposed ideas: the hard money policies which dominated monetary thinking in the late 19th century, and the monetary theories of [[John Maynard Keynes]], who, working in the inter-war period during the failure of the restored [[gold standard]], proposed a demand-driven model for money which was the foundation of [[macroeconomics]]. While Keynes had focused on the value stability of currency, with the resulting panics based on an insufficient money supply leading to alternate currency and collapse, then Friedman focused on price stability, which is the equilibrium between supply and demand for money. |

|||

==Description== |

|||

The result was summarized in a historical analysis of monetary policy, ''Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960'', which Friedman coauthored with [[Anna Schwartz]]. The book attributed inflation to excess money supply generated by a central bank. It attributed deflationary spirals to the reverse effect of a failure of a central bank to support the [[money supply]] during a [[liquidity]] crunch. |

|||

Monetarism is an economic theory that focuses on the [[macroeconomics|macroeconomic]] effects of the [[supply of money]] and [[central banking]]. Formulated by [[Milton Friedman]], it argues that excessive expansion of the money supply is inherently [[inflation]]ary, and that monetary authorities should focus solely on maintaining [[price stability]]. |

|||

Monetarist theory draws its roots from the [[quantity theory of money]], a centuries-old economic theory which had been put forward by various economists, among them [[Irving Fisher]] and [[Alfred Marshall]], before Friedman restated it in 1956.<ref name=Dimand>{{cite book|last1=Dimand |first1=Robert W. |chapter=Monetary Economics, History of |title=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |date=2016 |pages=1–13 |doi=10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2721-1 |url=https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2721-1 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan UK |language=en}}</ref><ref>Milton Friedman (1956), "The Quantity Theory of Money: A Restatement" in ''Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money'', edited by M. Friedman.]</ref> |

|||

Friedman originally proposed a fixed ''monetary rule'', called [[Friedman's k-percent rule]], where the money supply would be calculated by known macroeconomic and financial factors, targeting a specific level or range of inflation. Under this rule, would be no leeway for the central reserve bank (money supply increases could be determined "by a computer"), and business could anticipate all monetary policy decisions. In some contexts, "monetarism" is associated primarily with this approach to monetary policy, and is generally recognized to have been unsuccessful and impractical.<ref>[http://www.thomaspalley.com/?p=59 Thomas Palley], "Milton Friedman: The Great Conservative Partison"</ref><ref>http://online.wsj.com/public/article/SB116369744597625238-foIWt7vDyt4ralPtdifXt5Ux3Lo_20061216.html By Greg Ip and Mark Whitehouse, "How Milton Friedman Changed Economics, Policy and Markets", The Wall Street Journal, November 17, 2006; Page A1</ref> |

|||

== |

===Monetary history of the United States=== |

||

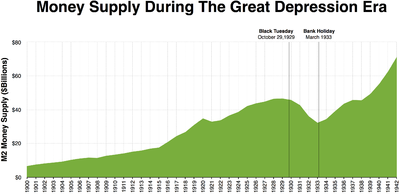

[[File:Money_supply_during_the_great_depression_era.png|400px|thumb|right| Money supply decreased significantly between [[Black Tuesday]] and the [[Emergency Banking Act|Bank Holiday in March 1933]] in the wake of massive [[bank runs]] across the United States.]] |

|||

The rise of monetarism within mainstream economics dates mostly from [[Milton Friedman]]'s 1956 restatement of the [[quantity theory of money]]. Friedman argued that the demand for money depended predictably on several major economic variables. Thus, were the [[money supply]] expanded, people would not simply wish to hold the extra money in idle money balances; i.e., if they were in equilibrium before the increase, they were already holding money balances to suit their requirements, and thus after the increase they would have money balances surplus to their requirements. These excess money balances would therefore be spent and hence aggregate demand would rise. Similarly, if the money supply were reduced people would want to replenish their holdings of money by reducing their spending. Thus Friedman challenged the Keynesian assertion that "money does not matter"; he argued that the supply of money does affect the amount of spending in an economy. Thus the word 'monetarist' was coined. |

|||

Monetarists argued that central banks sometimes caused major unexpected fluctuations in the money supply. Friedman asserted that actively trying to stabilize demand through monetary policy changes can have negative unintended consequences.<ref name=Blanchard>{{cite book |last1=Blanchard |first1=Olivier |last2=Amighini |first2=Alessia |last3=Giavazzi |first3=Francesco |title=Macroeconomics: a European perspective |date=2017 |publisher=Pearson |isbn=978-1-292-08567-8 |edition=3rd}}</ref>{{rp|511-512}} In part he based this view on the historical analysis of monetary policy, ''[[A Monetary History of the United States|A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960]]'', which he coauthored with [[Anna Schwartz]] in 1963. The book attributed inflation to excess money supply generated by a central bank. It attributed deflationary spirals to the reverse effect of a failure of a central bank to support the [[money supply]] during a [[Market liquidity|liquidity]] crunch.<ref>{{cite book|first=Michael D.|last=Bordo|date=1989|title=Money, History, & International Finance: Essays in Honor of Anna J. Schwartz|chapter=The Contribution of ''A Monetury History''|page=[https://archive.org/details/moneyhistoryinte0000unse/page/46 46]|department=The Increase in Reserve Requirements, 1936-37|isbn=0-226-06593-6|publisher=University of Chicago Press|access-date=2019-07-25|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/moneyhistoryinte0000unse/page/46|citeseerx=10.1.1.736.9649}}</ref> In particular, the authors argued that the [[Great Depression]] of the 1930s was caused by a massive contraction of the money supply (they deemed it "the [[Great Contraction]]"<ref name=FriedmanSchwartz>{{cite book|author1=Milton Friedman|author2=Anna Schwartz|title=The Great Contraction, 1929–1933|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=-lCArZfazBkC&q=%22Regarding%20the%20Great%20Depression%20You're%20right%20We%20did%20it%22|year=2008|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-0-691-13794-0|edition=New}}</ref>), and not by the lack of investment that Keynes had argued. They also maintained that post-war inflation was caused by an over-expansion of the money supply. They made famous the assertion of monetarism that "inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon." |

|||

===Fixed monetary rule=== |

|||

The rise of the popularity of monetarism in political circles accelerated when Keynesian economics seemed unable to explain or cure the seemingly contradictory problems of rising [[unemployment]] and [[inflation (economics)|inflation]] in response to the collapse of the [[Bretton Woods system]] in 1972 and the [[1973 oil crisis|oil shocks of 1973]]. On the one hand, higher unemployment seemed to call for Keynesian [[reflation]], but on the other hand rising inflation seemed to call for Keynesian [[deflation (economics)|deflation]]. The result was a significant disillusionment with Keynesian demand management: a Democratic President [[Jimmy Carter]] appointed a monetarist Federal Reserve chief [[Paul Volcker]] who made inflation fighting his primary objective, and restricted the money supply to tame inflation in the economy. The result was the most severe [[recession]] of the post-war period, but also the creation of the desired price stability. |

|||

Friedman proposed a fixed ''monetary rule'', called [[Friedman's k-percent rule]], where the money supply would be automatically increased by a fixed percentage per year. The rate should equal the growth rate of real [[GDP]], leaving the price level unchanged. For instance, if the economy is expected to grow at 2 percent in a given year, the Fed should allow the money supply to increase by 2 percent. Because [[Discretionary policy|discretionary monetary policy]] would be as likely to destabilise as to stabilise the economy, Friedman advocated that the Fed be bound to fixed rules in conducting its policy.<ref name=IMF/> |

|||

Monetarists not only sought to explain present problems; they also interpreted historical ones. Milton Friedman and [[Anna Schwartz]] in their book ''A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960'' argued that the [[Great Depression]] of 1930 was caused by a massive contraction of the money supply and not by the lack of investment Keynes had argued. They also maintained that post-war inflation was caused by an over-expansion of the money supply. They coined the famous assertion of monetarism that 'inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon'. At first, to many economists whose perceptions had been set by Keynesian ideas, it seemed that the Keynesian vs. monetarist debate was merely about whether fiscal or [[monetary policy]] was the more effective tool of demand management. By the mid-1970s, however, the debate had moved on to more profound matters when monetarists presented a more fundamental challenge to Keynesian orthodoxy. |

|||

===Opposition to the gold standard=== |

|||

Many monetarists sought to resurrect the pre-Keynesian view that market economies are inherently stable in the absence of major unexpected fluctuations in the money supply. Because of this belief in the stability of free-market economies they asserted that active demand management (e.g. by the means of increasing government spending) is unnecessary and indeed likely to be harmful. The basis of this argument is an equilibrium between "stimulus" fiscal spending and future interest rates. In effect, Friedman's model argues that current fiscal spending creates as much of a drag on the economy by increased interest rates as it creates present consumption: that it has no real effect on total demand, merely that of shifting demand from the investment sector (I) to the consumer sector (C). |

|||

Most monetarists oppose the [[gold standard]]. Friedman viewed a pure gold standard as impractical. For example, whereas one of the benefits of the gold standard is that the intrinsic limitations to the growth of the money supply by the use of gold would prevent inflation, if the growth of population or increase in trade outpaces the money supply, there would be no way to counteract deflation and reduced liquidity (and any attendant recession) except for the mining of more gold. But he also admitted that if a government was willing to surrender control over its monetary policy and not to interfere with economic activities, a gold-based economy would be possible.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.fff.org/freedom/0399b.asp|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121114140436/http://fff.org/freedom/0399b.asp|url-status=dead|title=Monetary Central Planning and the State, Part 27: Milton Friedman's Second Thoughts on the Costs of Paper Money|archive-date=November 14, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

==Rise== |

|||

== Monetarism in practice == |

|||

[[Clark Warburton]] is credited with making the first solid empirical case for the monetarist interpretation of [[business fluctuation]]s in a series of papers from 1945.<ref name="Cagan"/><sup>p. 493</sup> Within [[mainstream economics]], the rise of monetarism started with [[Milton Friedman]]'s 1956 restatement of the [[quantity theory of money]]. Friedman argued that the [[demand for money]] could be described as depending on a small number of economic variables.<ref name="hilbertcorporation">{{cite journal |first=Milton |last=Friedman |year=1970 |title=A Theoretical Framework for Monetary Analysis |journal=[[Journal of Political Economy]] |volume=78 |issue=2 |pages=193–238 [p. 210] |jstor=1830684 |doi=10.1086/259623|s2cid=154459930 }}</ref> |

|||

Thus, according to Friedman, when the [[money supply]] expanded, people would not simply wish to hold the extra money in idle money balances; i.e., if they were in equilibrium before the increase, they were already holding money balances to suit their requirements, and thus after the increase they would have money balances surplus to their requirements. These excess money balances would therefore be spent and hence [[aggregate demand]] would rise. Similarly, if the money supply were reduced people would want to replenish their holdings of money by reducing their spending. In this, Friedman challenged a simplification attributed to Keynes suggesting that "money does not matter."<ref name="hilbertcorporation" /> Thus the word 'monetarist' was coined. |

|||

The crucibles of economic theories are the cataclysmic events which reshape economic activity. Hence, major economic theories which aspire to a policy role must explain the great deflationary waves of the late 19th Century with their repeated panics, the Great Depression which began in the late 1920s and peaked in early 1933, and the [[stagflation]] period beginning with the uncoupling of exchange rates in 1972. |

|||

The popularity of monetarism picked up in political circles when the prevailing view of [[Neoclassical synthesis|neo-Keynesian economics]] seemed unable to explain the contradictory problems of rising [[unemployment]] and [[inflation (economics)|inflation]] in response to the [[Nixon shock]] in 1971 and the [[1973 oil crisis|oil shocks of 1973]]. On one hand, higher unemployment seemed to call for [[reflation]], but on the other hand rising inflation seemed to call for [[disinflation (economics)|disinflation]]. The social-democratic [[post-war consensus]] that had prevailed in [[First World|first world countries]] was thus called into question by the rising [[Neoliberalism|neoliberal]] political forces.<ref name="harvey1"/> |

|||

Monetarists argue that there was no inflationary investment boom in the 1920s, in contrast to both Keynesians and to economists of the [[Austrian School]], who argue that there was significant asset inflation and unsustainable GNP growth during the 1920s. Instead, monetarist thinking centers on the contraction of the M1 during the 1931-1933 period, and argues from there that the Federal Reserve could have avoided the Great Depression by moves to provide sufficient liquidity. In essence, they argue that there was an insufficient supply of money. This argument is supported by macroeconomic data, such as price stability in the 1920s and the slow rise of the money supply.{{Fact|date=June 2008}} |

|||

=== Monetarism in the US and the UK === |

|||

The counterargument is that microeconomic data support the conclusion of a poorly distributed pooling of liquidity in the 1920s, caused by excessive easing of credit. This viewpoint is argued by followers of [[Ludwig von Mises]], who stated at the time that the expansion was unsustainable, and at the same time by [[Keynes]], whose ideas were included in [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]]'s first inaugural address. |

|||

In 1979, United States President [[Jimmy Carter]] appointed as Federal Reserve Chief [[Paul Volcker]], who made fighting inflation his primary objective, and who restricted the money supply (in accordance with the [[Friedman rule]]) to tame inflation in the economy. The result was a major rise in interest rates, not only in the United States; but worldwide. The "Volcker shock" continued from 1979 to the summer of 1982, decreasing inflation and increasing unemployment.<ref>Reichart Alexandre & Abdelkader Slifi (2016). 'The Influence of Monetarism on Federal Reserve Policy during the 1980s.' Cahiers d'économie Politique/Papers in Political Economy, (1), pp. 107–50. https://www.cairn.info/revue-cahiers-d-economie-politique-2016-1-page-107.htm</ref> |

|||

From their conclusion that incorrect central bank policy is at the root of large swings in inflation and price instability, monetarists argued that the primary motivation for excessive easing of central bank policy is to finance fiscal deficits by the central government. Hence, restraint of government spending is the most important single target to restrain excessive monetary growth. |

|||

By the time [[Margaret Thatcher]], Leader of the [[Conservative Party (UK)|Conservative Party]] in the [[United Kingdom]], won the [[1979 United Kingdom general election|1979 general election]] defeating the sitting [[Labour Party (UK)|Labour Government]] led by [[James Callaghan]], the UK had endured several years of severe [[inflation]], which was rarely below the 10% mark and by the time of the May 1979 general election, stood at 10.3%.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Healey |first=Nigel M. |date=1990 |title=Fighting Inflation In Britain |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/40721141 |journal=Challenge |volume=33 |issue=2 |pages=37–41 |issn=0577-5132}}</ref> Thatcher implemented monetarism as the weapon in her battle against inflation, and succeeded at reducing it to 4.6% by 1983. However, [[unemployment in the United Kingdom]] increased from 5.7% in 1979 to 12.2% in 1983, reaching 13.0% in 1982; starting with the first quarter of 1980, the UK economy contracted in terms of real gross domestic product for six straight quarters.<ref>{{cite web|title=Real Gross Domestic Product for United Kingdom, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis|date=January 1975|url=https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CLVMNACSAB1GQUK|access-date=December 16, 2018}}</ref> |

|||

With the failure of demand-driven fiscal policies to restrain inflation and produce growth in the 1970s, the way was paved for a new change in policy that focused on fighting inflation as the cardinal responsibility for the central bank. In typical economic theory, this would be accompanied by austerity shock treatment, as is generally recommended by the [[International Monetary Fund]]. Indeed in the [[United Kingdom]], government spending was slashed in the late 70s and early 80s with the political ascendance of Margaret Thatcher, whereas in the [[United States]], real government spending increased much faster during Reagan's first four years (4.22%/year) than it did under Carter (2.55%/year) [ref: 2006 Economic Report of the President, Table B-78 and B-60]. In the ensuing short term, unemployment in both countries remained stubbornly high while central banks raised interest rates to restrain credit. However, the policies of both countries' central banks dramatically brought down the inflation rates (e.g. the United State's inflation rate fell from almost 14% in 1980 to around 3% in 1983), allowing the liberalisation of credit and the reduction in interest rates which paved the way for the ultimately inflationary economic booms of the 1980s. Some claim that the use of credit to fuel economic expansion is itself an anti-monetarist tool, as it can be argued that an increase in money supply alone constitutes inflation. |

|||

==Decline== |

|||

Monetarism re-asserted itself in central bank policy in western governments at the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, with a contraction in spending and in the money supply ending the booms experienced in the US and UK. |

|||

Monetarist ascendancy was brief, however.<ref name=IMF>{{cite journal |last1=Jahan |first1=Sarwat |last2=Papageorgiou |first2=Chris |title=Back to Basics What Is Monetarism?: Its emphasis on money’s importance gained sway in the 1970s |journal=Finance & Development |date=28 February 2014 |volume=51 |issue=001 |doi=10.5089/9781484312025.022.A012 |url=https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/022/0051/001/article-A012-en.xml |access-date=16 October 2023 |language=en}}</ref> The period when major central banks focused on targeting the growth of money supply, reflecting monetarist theory, lasted only for a few years, in the US from 1979 to 1982.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Mattos |first1=Olivia Bullio |title=Handbook of Economic Stagnation |date=1 January 2022 |publisher=Academic Press |isbn=978-0-12-815898-2 |pages=341–359 |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128158982000069 |access-date=16 October 2023 |chapter=Chapter Seventeen - Monetary policy after the subprime crisis: a Post-Keynesian critique}}</ref> |

|||

With the [[Black Monday (1987)|crash of 1987]], questioning of the prevailing monetarist policy began. Monetarists argued that the 1987 stock market decline was simply a correction between conflicting monetary policies in the United States and Europe. Critics of this viewpoint became louder as Japan slid into a sustained deflationary spiral and the collapse of the savings-and-loan banking system in the United States pointed to larger structural changes in the economy. |

|||

The money supply is useful as a policy target only if the relationship between money and nominal GDP, and therefore inflation, is stable and predictable. This implies that the velocity of money must be predictable. In the 1970s velocity had seemed to increase at a fairly constant rate, but in the 1980s and 1990s velocity became highly unstable, experiencing unpredictable periods of increases and declines. Consequently, the stable correlation between the money supply and nominal GDP broke down, and the usefulness of the monetarist approach came into question. Many economists who had been convinced by monetarism in the 1970s abandoned the approach after this experience.<ref name=IMF/> |

|||

In the late 1980s, [[Paul Volcker]] was succeeded by [[Alan Greenspan]], a leading monetarist. His handling of monetary policy in the run-up to the 1991 recession was criticized from the right as being excessively tight, and costing [[George H. W. Bush]] re-election. The incoming Democratic president [[Bill Clinton]] reappointed Alan Greenspan, and kept him as a core member of his economic team. Greenspan, while still fundamentally monetarist in orientation, argued that doctrinaire application of theory was insufficiently flexible for central banks to meet emerging situations. |

|||

The changing velocity originated in shifts in the [[demand for money]] and created serious problems for the central banks. This provoked a thorough rethinking of monetary policy. In the early 1990s central banks started focusing on targeting inflation directly using the short-run [[interest rate]] as their central policy variable, abandoning earlier emphasis on money growth. The new strategy proved successful, and today most major central banks follow a flexible [[inflation targeting]].<ref name=Blanchard/>{{rp|483-485}} |

|||

The crucial test of this flexible response by the Federal Reserve was the [[Asian financial crisis]] of 1997-1998, which the Federal Reserve met by flooding the world with dollars, and organizing a bailout of [[Long-Term Capital Management]]. Some have argued that 1997-1998 represented a monetary policy bind—as the early 1970s had represented a fiscal policy bind—and that while asset inflation had crept into the United States, demanding that the Fed tighten, the Federal Reserve needed to ease liquidity in response to the capital flight from Asia. Greenspan himself noted this when he stated that the American stock market showed signs of [[irrational exuberance|irrationally high valuations.]] |

|||

==Legacy== |

|||

In 2000, Alan Greenspan raised interest rates several times; these actions were believed by many to have caused the bursting of the dot-com bubble. In autumn of 2001, as a decisive reaction to September 11th attacks and the various corporate scandals which undermined the economy, the Greenspan-led Federal Reserve initiated a series of interest cuts that brought down the Federal Funds rate to 1% in 2004. His critics, notably [[Steve Forbes]] attributed the rapid rise in commodity prices and gold to Greenspan's loose monetary policy which is causing excessive asset inflation and a weak dollar. By late 2004 the price of gold was higher than its 12 year moving average. |

|||

Even though monetarism failed in practical policy, and the close attention to money growth which was at the heart of monetarist analysis is rejected by most economists today, some aspects of monetarism have found their way into modern mainstream economic thinking.<ref name=IMF/><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Long |first1=De |last2=Bradford |first2=J. |title=The Triumph of Monetarism? |journal=Journal of Economic Perspectives |date=March 2000 |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=83–94 |doi=10.1257/jep.14.1.83 |url=https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.14.1.83 |access-date=16 October 2023 |language=en |issn=0895-3309}}</ref> Among them are the belief that controlling inflation should be a primary responsibility of the central bank.<ref name=IMF/> It is also widely recognized that monetary policy, as well as fiscal policy, can affect output in the short run.<ref name=Blanchard/>{{rp|511}} In this way, important monetarist thoughts have been subsumed into the [[new neoclassical synthesis]] or consensus view of macroeconomics that emerged in the 2000s.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Goodfriend |first1=Marvin |last2=King |first2=Robert G. |title=NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1997, Volume 12 |date=January 1997 |publisher=MIT Press |pages=231–296 |url=http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11040 |chapter=The New Neoclassical Synthesis and the Role of Monetary Policy}}</ref><ref name=Blanchard/>{{rp|518}} |

|||

Alan Greenspan is blamed by the followers of the Austrian School for creating excessive liquidity which caused lending standards to deteriorate resulting in the housing bubble of 2004-2006. Currently the American Federal Reserve follows a modified form of monetarism, where broader ranges of intervention are possible in light of temporary instabilities in market dynamics. This form does not yet have a generally accepted name. |

|||

==Notable proponents== |

|||

In Europe, the European Central Bank follows a more [http://www.ecb.int/mopo/intro/html/role.en.html orthodox form of monetarism], with tighter controls over inflation and spending targets as mandated by the [[Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union]] under the [[Maastricht Treaty]] to support the [[euro]]. This more orthodox monetary policy is in the wake of credit easing in the late 1980s and 1990s to fund German reunification, which was blamed for the weakening of European currencies in the late 1990s. |

|||

{{div col|colwidth=20em}} |

|||

* [[Karl Brunner (economist)|Karl Brunner]] |

|||

== The current state of monetarism== |

|||

Since 1990, the classical form of monetarism has been questioned because of events which many economists have interpreted as being inexplicable in monetarist terms, namely the unhinging of the money supply growth from inflation in the 1990s and the failure of pure monetary policy to stimulate the economy in the 2001-2003 period. [[Alan Greenspan]], former chairman of the [[Federal Reserve]], argued that the 1990s decoupling was explained by a [[virtuous cycle]] of productivity and investment on one hand, and a certain degree of "[[irrational exuberance]]" in the investment sector. Economist [[Robert Solow]] of MIT suggested that the 2001-2003 failure of the expected economic recovery should be attributed not to monetary policy failure but to the breakdown in productivity growth in crucial sectors of the economy, most particularly retail trade. He noted that five sectors produced all of the productivity gains of the 1990s, and that while the growth of retail and wholesale trade produced the smallest growth, they were by far the largest sectors of the economy experiencing net increase of productivity. "2% may be peanuts, but being the single largest sector of the economy, that's an awful lot of peanuts." |

|||

There are also arguments which link monetarism and [[macroeconomics]], and treat monetarism as a special case of Keynesian theory. The central test case over the validity of these theories would be the possibility of a [[liquidity trap]], like that experienced by Japan. [[Ben Bernanke]], Princeton Professor and current Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, has argued that monetarism could respond to zero interest rate conditions by direct expansion of the money supply. In his words "We have the keys to the printing press, and we are not afraid to use them." Another popular economist, [[Paul Krugman]], has advanced the counterargument that this would have a corresponding devaluationary effect, like the sustained low interest rates of 2001-2004 produced against world currencies. |

|||

[[David Hackett Fischer]], in his study ''The Great Wave'', questioned the implicit basis of monetarism by examining long periods of secular inflation that stretched over decades. In doing so, he produced data which suggests that prior to a wave of [[monetary inflation]], there is a wave of commodity inflation, which governments respond to, rather than lead. Whether this formulation undermines the monetary data which underpins the fundamental work of monetarism is still a matter of contention. |

|||

Monetarists of the Milton Friedman school of thought believed in the 1970s and 1980s that the growth of the money supply should be based on certain formulations related to economic growth. As such, they can be regarded as advocates of a monetary policy based on a "quantity of money" target. This can be contrasted with the monetary policy advocated by [[supply side economics]] and the [[Austrian School]] which are based on a "value of money" target. Austrian economists criticise monetarism for not recognizing the citizens' subjective value of money and trying to create an objective value through supply and demand. |

|||

These disagreements, along with the role of monetary policy in trade liberalization, international investment, and central bank policy, remain lively topics of investigation and argument. |

|||

==Monetarism and gold standard== |

|||

While most monetarists believe that government action is at the root of [[inflation]], very few advocate a return to the [[gold standard]]. Friedman, for example, viewed the gold standard as highly impractical.{{Fact|date=February 2008}} |

|||

==List of Influential Monetarists== |

|||

* [[Karl Brunner]] |

|||

* [[Phillip D. Cagan]] |

* [[Phillip D. Cagan]] |

||

* [[Tim Congdon]] |

|||

* [[Milton Friedman]] |

* [[Milton Friedman]] |

||

* [[Alan Greenspan]] |

|||

* [[David Laidler|David E.W. Laidler]] |

|||

* [[Steve Hanke]] |

|||

* [[Allan Meltzer|Allan H. Meltzer]] |

|||

* [[David Laidler]] |

|||

* [[Anna Schwartz|Anna J. Schwartz]] |

|||

* [[Allan H. Meltzer]] |

|||

* [[Anna Schwartz]] |

|||

* [[Margaret Thatcher]] |

* [[Margaret Thatcher]] |

||

* [[Paul Volcker]] |

|||

* [[Clark Warburton]] |

|||

==Articles and books== |

|||

{{div col end}} |

|||

* [http://chevallier.turgot.org/a363-Monetary_creation_aggregates_and_GDP_growth.html '''Monetary creation, aggregates and GDP growth'''] On the inverse relation between Excess Money Supply and Growth. - '' J.P. Chevallier'' |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

{{Portal|Philosophy|Economics}} |

|||

*[[Inflation targeting]] |

|||

{{div col}} |

|||

*[[Macroeconomics]] |

|||

* [[Chicago school of economics]] |

|||

*[[Political economy]] |

|||

* [[Demurrage (currency)]] |

|||

*[[List of finance topics]] |

|||

* [[Fiscalism]] (usually contrasted to monetarism) |

|||

*[[List of economics topics]] |

|||

* [[Market monetarism]] |

|||

*[[Chicago school (economics)|Chicago School]] |

|||

* [[Modern Monetary Theory]] |

|||

* [[Money creation]] - process in which [[commercial bank|private banks]] (primarily) or [[Central bank]]s ([[quantitative easing]]) create money |

|||

{{div col end}} |

|||

== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

*[http://cepa.newschool.edu/het/schools/monetar.htm "Monetarism"] at The New School's Economics Department's History of Economic Thought website. |

|||

*[http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Monetarism.html Monetarism] by [[Allan Meltzer]]. ''[[Concise encyclopedia of economics]]'' on [[Econlib]] |

|||

*[http://www.economist.com/research/Economics/alphabetic.cfm?LETTER=M#MONETARISM Monetarism] from the Economics A-Z of [[The Economist]] |

|||

==Further references== |

|||

{{macroeconomics-footer}} |

|||

* Andersen, Leonall C., and Jerry L. Jordan, 1968. "Monetary and Fiscal Actions: A Test of Their Relative Importance in Economic Stabilisation", Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ''Review'' (November), pp. 11–24. [http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/86/10/Fiscal_Oct1986.pdf PDF] (30 sec. load: press '''+''') and [http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/86/10/Fiscal_Oct1986.pdf=1 HTML.] |

|||

* _____, 1969. "Monetary and Fiscal Actions: A Test of Their Relative Importance in Economic Stabilisation — Reply", Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis ''Review'' (April), pp. 12–16. [http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/69/04/Reply_Apr1969.pdf PDF] (15 sec. load; press '''+''') and [http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/69/04/Reply_Apr1969.pdf=1 HTML.] |

|||

* Brunner, Karl, and Allan H. Meltzer, 1993. ''Money and the Economy: Issues in Monetary Analysis'', Cambridge. [https://books.google.com/books?id=eGjfH47Roj4C&q=Brunner+Meltzer+%22Money+and+the+Economy:+Issues++in+Monetary+Analysis' Description] and chapter previews, pp. [https://books.google.com/books?id=eGjfH47Roj4C&dq=Brunner+Meltzer+%22Money+and+the+Economy:+Issues++in+Monetary+Analysis%27.&pg=PR9 ix]–[https://books.google.com/books?id=eGjfH47Roj4C&dq=Brunner+Meltzer+%22Money+and+the+Economy:+Issues++in+Monetary+Analysis%27.&pg=PR10 x.] |

|||

* Cagan, Phillip, 1965. ''Determinants and Effects of Changes in the Stock of Money, 1875–1960''. NBER. Foreword by Milton Friedman, pp. xiii–xxviii. [https://www.nber.org/books/caga65-1 Table of Contents.] |

|||

* Friedman, Milton, ed. 1956. ''Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money'', Chicago. Chapter 1 is previewed at Friedman, 2005, ch. 2 link. |

|||

* _____, 1960. ''A Program for Monetary Stability''. Fordham University Press. |

|||

* _____, 1968. "The Role of Monetary Policy", ''American Economic Review'', 58(1), pp. [https://web.archive.org/web/20100529152742/http://www.nvcc.edu/home/jmin/ReadingStuff/The%20Role%20of%20Monetary%20Policy%20by%20Friedman.pdf 1–17] (press '''+'''). |

|||

* _____, [1969] 2005. ''The Optimum Quantity of Money''. [https://books.google.com/books?id=XVCgcHQS_nQC Description] and [https://books.google.com/books?id=XVCgcHQS_nQC table of contents], with previews of 3 chapters. |

|||

* Friedman, Milton, and David Meiselman, 1963. "The Relative Stability of Monetary Velocity and the Investment Multiplier in the United States, 1897–1958", in ''Stabilization Policies'', pp. 165–268. Prentice-Hall/Commission on Money and Credit, 1963. |

|||

* Friedman, Milton, and Anna Jacobson Schwartz, 1963a. "Money and Business Cycles", ''Review of Economics and Statistics'', 45(1), Part 2, Supplement, p. [https://www.jstor.org/pss/1927148 p. 32]–64. Reprinted in Schwartz, 1987, ''Money in Historical Perspective'', ch. 2. |

|||

* _____. 1963b. ''A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960''. Princeton. Page-searchable links to chapters on [https://books.google.com/books?id=Q7J_EUM3RfoC&dq=%22A+Monetary+History+of+the+United+States,+1867-1960%22&pg=PR9 1929-41] and [https://books.google.com/books?id=Q7J_EUM3RfoC&dq=%22A+Monetary+History+of+the+United+States,+1867-1960%22&pg=PR10 1948–60] |

|||

* [[Harry Gordon Johnson|Johnson, Harry G.]], 1971. "The Keynesian Revolutions and the Monetarist Counter-Revolution", ''American Economic Review'', 61(2), p. [https://www.jstor.org/pss/1816968 p. 1]–14. Reprinted in [[John Cunningham Wood]] and Ronald N. Woods, ed., 1990, ''Milton Friedman: Critical Assessments'', v. 2, p. [https://books.google.com/books?id=t4-nLZRU_GAC&pg=PA72 p. 72] [https://books.google.com/books?id=t4-nLZRU_GAC –] 88. Routledge, |

|||

* Laidler, David E.W., 1993. ''The Demand for Money: Theories, Evidence, and Problems'', 4th ed. [https://www.amazon.co.uk/Demand-Money-Theories-HarperCollins-Economics/dp/0065010981 Description.] |

|||

* [[Anna J. Schwartz|Schwartz, Anna J.]], 1987. ''Money in Historical Perspective'', University of Chicago Press. [https://books.google.com/books?id=Oco-yeAJhaEC Description] and Chapter-preview links, pp. [https://books.google.com/books?id=Oco-yeAJhaEC&pg=PR7 vii]-[https://books.google.com/books?id=Oco-yeAJhaEC&pg=PR8 viii.] |

|||

* Warburton, Clark, 1966. ''Depression, Inflation, and Monetary Policy; Selected Papers, 1945–1953'' Johns Hopkins Press. [https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0801806550 Amazon Summary] in Anna J. Schwartz, ''Money in Historical Perspective'', 1987. |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Unreferenced|date=May 2007}} |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20070821085549/http://cepa.newschool.edu/het/schools/monetar.htm "Monetarism"] at The New School's Economics Department's History of Economic Thought website. |

|||

* {{cite encyclopedia |last1=McCallum |first1=Bennett T. |author-link1= Bennett McCallum |editor= David R. Henderson |editor-link= David R. Henderson |encyclopedia=[[Concise Encyclopedia of Economics]] |title=Monetarism |url=http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Monetarism.html |year=2008 |edition= 2nd |publisher=[[Library of Economics and Liberty]] |location=Indianapolis |isbn=978-0865976658 |oclc=237794267}} |

|||

* [http://www.economist.com/economics-a-to-z/m#node-21529789 Monetarism] from the Economics A–Z of [[The Economist]] |

|||

{{Economics}} |

|||

[[Category:Economic theories]] |

|||

{{Macroeconomics}} |

|||

{{Chiconomists}} |

|||

[[Category:Schools of economic thought and methodology]] |

|||

{{Milton Friedman}} |

|||

{{Means of Exchange}} |

|||

{{Neoliberalism}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Monetary economics]] |

|||

[[cs:Monetarismus]] |

|||

[[Category:Milton Friedman]] |

|||

[[da:Monetarisme]] |

|||

[[Category:20th century in economic history]] |

|||

[[de:Monetarismus]] |

|||

[[Category:21st century in economic history]] |

|||

[[et:Monetarism]] |

|||

[[Category:Schools of economic thought]] |

|||

[[es:Escuela monetarista]] |

|||

[[eo:Kvanta teorio de mono]] |

|||

[[fr:Monétarisme]] |

|||

[[it:Monetarismo]] |

|||

[[he:מוניטריזם]] |

|||

[[nl:Monetarisme]] |

|||

[[ja:マネタリスト]] |

|||

[[no:Monetarisme]] |

|||

[[pl:Monetaryzm]] |

|||

[[pt:Monetarismo]] |

|||

[[ru:Монетаризм]] |

|||

[[simple:Monetarism]] |

|||

[[fi:Monetaristinen taloustiede]] |

|||

[[sv:Monetarism]] |

|||

[[vi:Chủ nghĩa tiền tệ]] |

|||

[[uk:Монетаризм]] |

|||

[[zh:货币主义]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 09:11, 15 April 2024

| Part of a series on |

| Macroeconomics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of policy-makers in controlling the amount of money in circulation. It gained prominence in the 1970s, but was mostly abandoned as a direct guidance to monetary policy during the following decade because of the rise of inflation targeting through movements of the official interest rate.

The monetarist theory states that variations in the money supply have major influences on national output in the short run and on price levels over longer periods. Monetarists assert that the objectives of monetary policy are best met by targeting the growth rate of the money supply rather than by engaging in discretionary monetary policy.[1] Monetarism is commonly associated with neoliberalism.[2]

Monetarism is mainly associated with the work of Milton Friedman, who was an influential opponent of Keynesian economics, criticising Keynes's theory of fighting economic downturns using fiscal policy (government spending). Friedman and Anna Schwartz wrote an influential book, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960, and argued "that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon".[3]

Though Friedman opposed the existence of the Federal Reserve,[4] he advocated, given its existence, a central bank policy aimed at keeping the growth of the money supply at a rate commensurate with the growth in productivity and demand for goods. Money growth targeting was mostly abandoned by the central banks who tried it, however. Contrary to monetarist thinking, the relation between money growth and inflation proved to be far from tight. Instead, starting in the early 1990s, most major central banks turned to direct inflation targeting, relying on steering short-run interest rates as their main policy instrument.[5]: 483–485 Afterwards, monetarism was subsumed into the new neoclassical synthesis which appeared in macroeconomics around 2000.

Description[edit]

Monetarism is an economic theory that focuses on the macroeconomic effects of the supply of money and central banking. Formulated by Milton Friedman, it argues that excessive expansion of the money supply is inherently inflationary, and that monetary authorities should focus solely on maintaining price stability.

Monetarist theory draws its roots from the quantity theory of money, a centuries-old economic theory which had been put forward by various economists, among them Irving Fisher and Alfred Marshall, before Friedman restated it in 1956.[6][7]

Monetary history of the United States[edit]

Monetarists argued that central banks sometimes caused major unexpected fluctuations in the money supply. Friedman asserted that actively trying to stabilize demand through monetary policy changes can have negative unintended consequences.[5]: 511–512 In part he based this view on the historical analysis of monetary policy, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960, which he coauthored with Anna Schwartz in 1963. The book attributed inflation to excess money supply generated by a central bank. It attributed deflationary spirals to the reverse effect of a failure of a central bank to support the money supply during a liquidity crunch.[8] In particular, the authors argued that the Great Depression of the 1930s was caused by a massive contraction of the money supply (they deemed it "the Great Contraction"[9]), and not by the lack of investment that Keynes had argued. They also maintained that post-war inflation was caused by an over-expansion of the money supply. They made famous the assertion of monetarism that "inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon."

Fixed monetary rule[edit]

Friedman proposed a fixed monetary rule, called Friedman's k-percent rule, where the money supply would be automatically increased by a fixed percentage per year. The rate should equal the growth rate of real GDP, leaving the price level unchanged. For instance, if the economy is expected to grow at 2 percent in a given year, the Fed should allow the money supply to increase by 2 percent. Because discretionary monetary policy would be as likely to destabilise as to stabilise the economy, Friedman advocated that the Fed be bound to fixed rules in conducting its policy.[10]

Opposition to the gold standard[edit]

Most monetarists oppose the gold standard. Friedman viewed a pure gold standard as impractical. For example, whereas one of the benefits of the gold standard is that the intrinsic limitations to the growth of the money supply by the use of gold would prevent inflation, if the growth of population or increase in trade outpaces the money supply, there would be no way to counteract deflation and reduced liquidity (and any attendant recession) except for the mining of more gold. But he also admitted that if a government was willing to surrender control over its monetary policy and not to interfere with economic activities, a gold-based economy would be possible.[11]

Rise[edit]

Clark Warburton is credited with making the first solid empirical case for the monetarist interpretation of business fluctuations in a series of papers from 1945.[1]p. 493 Within mainstream economics, the rise of monetarism started with Milton Friedman's 1956 restatement of the quantity theory of money. Friedman argued that the demand for money could be described as depending on a small number of economic variables.[12]

Thus, according to Friedman, when the money supply expanded, people would not simply wish to hold the extra money in idle money balances; i.e., if they were in equilibrium before the increase, they were already holding money balances to suit their requirements, and thus after the increase they would have money balances surplus to their requirements. These excess money balances would therefore be spent and hence aggregate demand would rise. Similarly, if the money supply were reduced people would want to replenish their holdings of money by reducing their spending. In this, Friedman challenged a simplification attributed to Keynes suggesting that "money does not matter."[12] Thus the word 'monetarist' was coined.

The popularity of monetarism picked up in political circles when the prevailing view of neo-Keynesian economics seemed unable to explain the contradictory problems of rising unemployment and inflation in response to the Nixon shock in 1971 and the oil shocks of 1973. On one hand, higher unemployment seemed to call for reflation, but on the other hand rising inflation seemed to call for disinflation. The social-democratic post-war consensus that had prevailed in first world countries was thus called into question by the rising neoliberal political forces.[2]

Monetarism in the US and the UK[edit]

In 1979, United States President Jimmy Carter appointed as Federal Reserve Chief Paul Volcker, who made fighting inflation his primary objective, and who restricted the money supply (in accordance with the Friedman rule) to tame inflation in the economy. The result was a major rise in interest rates, not only in the United States; but worldwide. The "Volcker shock" continued from 1979 to the summer of 1982, decreasing inflation and increasing unemployment.[13]

By the time Margaret Thatcher, Leader of the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom, won the 1979 general election defeating the sitting Labour Government led by James Callaghan, the UK had endured several years of severe inflation, which was rarely below the 10% mark and by the time of the May 1979 general election, stood at 10.3%.[14] Thatcher implemented monetarism as the weapon in her battle against inflation, and succeeded at reducing it to 4.6% by 1983. However, unemployment in the United Kingdom increased from 5.7% in 1979 to 12.2% in 1983, reaching 13.0% in 1982; starting with the first quarter of 1980, the UK economy contracted in terms of real gross domestic product for six straight quarters.[15]

Decline[edit]

Monetarist ascendancy was brief, however.[10] The period when major central banks focused on targeting the growth of money supply, reflecting monetarist theory, lasted only for a few years, in the US from 1979 to 1982.[16]

The money supply is useful as a policy target only if the relationship between money and nominal GDP, and therefore inflation, is stable and predictable. This implies that the velocity of money must be predictable. In the 1970s velocity had seemed to increase at a fairly constant rate, but in the 1980s and 1990s velocity became highly unstable, experiencing unpredictable periods of increases and declines. Consequently, the stable correlation between the money supply and nominal GDP broke down, and the usefulness of the monetarist approach came into question. Many economists who had been convinced by monetarism in the 1970s abandoned the approach after this experience.[10]

The changing velocity originated in shifts in the demand for money and created serious problems for the central banks. This provoked a thorough rethinking of monetary policy. In the early 1990s central banks started focusing on targeting inflation directly using the short-run interest rate as their central policy variable, abandoning earlier emphasis on money growth. The new strategy proved successful, and today most major central banks follow a flexible inflation targeting.[5]: 483–485

Legacy[edit]

Even though monetarism failed in practical policy, and the close attention to money growth which was at the heart of monetarist analysis is rejected by most economists today, some aspects of monetarism have found their way into modern mainstream economic thinking.[10][17] Among them are the belief that controlling inflation should be a primary responsibility of the central bank.[10] It is also widely recognized that monetary policy, as well as fiscal policy, can affect output in the short run.[5]: 511 In this way, important monetarist thoughts have been subsumed into the new neoclassical synthesis or consensus view of macroeconomics that emerged in the 2000s.[18][5]: 518

Notable proponents[edit]

See also[edit]

- Chicago school of economics

- Demurrage (currency)

- Fiscalism (usually contrasted to monetarism)

- Market monetarism

- Modern Monetary Theory

- Money creation - process in which private banks (primarily) or Central banks (quantitative easing) create money

References[edit]

- ^ a b Phillip Cagan, 1987. "Monetarism", The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, Reprinted in John Eatwell et al. (1989), Money: The New Palgrave, pp. 195–205, 492–97.

- ^ a b Harvey, David (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928326-2.

- ^ Friedman, Milton (2008). Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691003542. OCLC 994352014.

- ^ Doherty, Brian (June 1995). "Best of Both Worlds". Reason. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Blanchard, Olivier; Amighini, Alessia; Giavazzi, Francesco (2017). Macroeconomics: a European perspective (3rd ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-1-292-08567-8.

- ^ Dimand, Robert W. (2016). "Monetary Economics, History of". The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 1–13. doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2721-1.

- ^ Milton Friedman (1956), "The Quantity Theory of Money: A Restatement" in Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, edited by M. Friedman.]

- ^ Bordo, Michael D. (1989). "The Contribution of A Monetury History". Money, History, & International Finance: Essays in Honor of Anna J. Schwartz. The Increase in Reserve Requirements, 1936-37. University of Chicago Press. p. 46. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.736.9649. ISBN 0-226-06593-6. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- ^ Milton Friedman; Anna Schwartz (2008). The Great Contraction, 1929–1933 (New ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13794-0.

- ^ a b c d e Jahan, Sarwat; Papageorgiou, Chris (28 February 2014). "Back to Basics What Is Monetarism?: Its emphasis on money's importance gained sway in the 1970s". Finance & Development. 51 (001). doi:10.5089/9781484312025.022.A012. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "Monetary Central Planning and the State, Part 27: Milton Friedman's Second Thoughts on the Costs of Paper Money". Archived from the original on November 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Friedman, Milton (1970). "A Theoretical Framework for Monetary Analysis". Journal of Political Economy. 78 (2): 193–238 [p. 210]. doi:10.1086/259623. JSTOR 1830684. S2CID 154459930.

- ^ Reichart Alexandre & Abdelkader Slifi (2016). 'The Influence of Monetarism on Federal Reserve Policy during the 1980s.' Cahiers d'économie Politique/Papers in Political Economy, (1), pp. 107–50. https://www.cairn.info/revue-cahiers-d-economie-politique-2016-1-page-107.htm

- ^ Healey, Nigel M. (1990). "Fighting Inflation In Britain". Challenge. 33 (2): 37–41. ISSN 0577-5132.

- ^ "Real Gross Domestic Product for United Kingdom, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis". January 1975. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ Mattos, Olivia Bullio (1 January 2022). "Chapter Seventeen - Monetary policy after the subprime crisis: a Post-Keynesian critique". Handbook of Economic Stagnation. Academic Press. pp. 341–359. ISBN 978-0-12-815898-2. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Long, De; Bradford, J. (March 2000). "The Triumph of Monetarism?". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 14 (1): 83–94. doi:10.1257/jep.14.1.83. ISSN 0895-3309. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Goodfriend, Marvin; King, Robert G. (January 1997). "The New Neoclassical Synthesis and the Role of Monetary Policy". NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1997, Volume 12. MIT Press. pp. 231–296.

Further references[edit]

- Andersen, Leonall C., and Jerry L. Jordan, 1968. "Monetary and Fiscal Actions: A Test of Their Relative Importance in Economic Stabilisation", Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review (November), pp. 11–24. PDF (30 sec. load: press +) and HTML.

- _____, 1969. "Monetary and Fiscal Actions: A Test of Their Relative Importance in Economic Stabilisation — Reply", Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review (April), pp. 12–16. PDF (15 sec. load; press +) and HTML.

- Brunner, Karl, and Allan H. Meltzer, 1993. Money and the Economy: Issues in Monetary Analysis, Cambridge. Description and chapter previews, pp. ix–x.

- Cagan, Phillip, 1965. Determinants and Effects of Changes in the Stock of Money, 1875–1960. NBER. Foreword by Milton Friedman, pp. xiii–xxviii. Table of Contents.

- Friedman, Milton, ed. 1956. Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, Chicago. Chapter 1 is previewed at Friedman, 2005, ch. 2 link.

- _____, 1960. A Program for Monetary Stability. Fordham University Press.

- _____, 1968. "The Role of Monetary Policy", American Economic Review, 58(1), pp. 1–17 (press +).

- _____, [1969] 2005. The Optimum Quantity of Money. Description and table of contents, with previews of 3 chapters.

- Friedman, Milton, and David Meiselman, 1963. "The Relative Stability of Monetary Velocity and the Investment Multiplier in the United States, 1897–1958", in Stabilization Policies, pp. 165–268. Prentice-Hall/Commission on Money and Credit, 1963.

- Friedman, Milton, and Anna Jacobson Schwartz, 1963a. "Money and Business Cycles", Review of Economics and Statistics, 45(1), Part 2, Supplement, p. p. 32–64. Reprinted in Schwartz, 1987, Money in Historical Perspective, ch. 2.

- _____. 1963b. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. Princeton. Page-searchable links to chapters on 1929-41 and 1948–60

- Johnson, Harry G., 1971. "The Keynesian Revolutions and the Monetarist Counter-Revolution", American Economic Review, 61(2), p. p. 1–14. Reprinted in John Cunningham Wood and Ronald N. Woods, ed., 1990, Milton Friedman: Critical Assessments, v. 2, p. p. 72 – 88. Routledge,

- Laidler, David E.W., 1993. The Demand for Money: Theories, Evidence, and Problems, 4th ed. Description.

- Schwartz, Anna J., 1987. Money in Historical Perspective, University of Chicago Press. Description and Chapter-preview links, pp. vii-viii.

- Warburton, Clark, 1966. Depression, Inflation, and Monetary Policy; Selected Papers, 1945–1953 Johns Hopkins Press. Amazon Summary in Anna J. Schwartz, Money in Historical Perspective, 1987.

External links[edit]

- "Monetarism" at The New School's Economics Department's History of Economic Thought website.

- McCallum, Bennett T. (2008). "Monetarism". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

- Monetarism from the Economics A–Z of The Economist