Qetesh: Difference between revisions

removed Category:Love and lust goddesses using HotCat |

פעמי-עליון (talk | contribs) m Templates |

||

| (42 intermediate revisions by 26 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Ancient Egyptian goddess}} |

|||

{{ |

{{for multi|the Stargate character|Qetesh (Stargate)|other uses|Qadesh (disambiguation)}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2021}} |

|||

{{Infobox deity |

{{Infobox deity |

||

| type = Egyptian |

| type = Egyptian |

||

| name = Qetesh |

| name = Qetesh |

||

| image = |

| image = File:Qadesh (Goddess).png |

||

| image_upright = .5 |

|||

| alt = |

| alt = |

||

| caption = A digital collage showing an image of Qetesh together with hieroglyphs taken from a separate Egyptian relief (the |

| caption = A digital collage showing an image of Qetesh together with hieroglyphs taken from a separate Egyptian relief<br />(the 'Triple Goddess stone') |

||

| god_of = |

| god_of = heavenly goddess |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| hiro = |

|||

| parents = [[Ptah]] or [[Ra (god)|Ra]]<ref>I. Cornelius, ''[http://www.religionswissenschaft.uzh.ch/idd/prepublications/e_idd_qudshu.pdf Qudshu]'', ''[http://www.religionswissenschaft.uzh.ch/idd/prepublication.php Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East]'' (electronic pre-publication), p. 1, 4</ref> |

|||

| abode = [[Kadesh (Syria)|Qadesh]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| equivalent1_type = Canaanite |

|||

| equivalent1 = [[Astarte]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Fertile Crescent myth (Levantine)}} |

|||

{{Middle Eastern deities}} |

|||

{{Ancient Egyptian religion}} |

{{Ancient Egyptian religion}} |

||

'''Qetesh''' (also '''Qadesh''', '''Qedesh''', '''Qetesh''', '''Kadesh''', '''Kedesh''', '''Kadeš''' or '''Qades''' {{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|ɑː|d|ɛ|ʃ}}) |

'''Qetesh''' (also '''Qodesh''', '''Qadesh''', '''Qedesh''', '''Qetesh''', '''Kadesh''', '''Kedesh''', '''Kadeš''' or '''Qades''' {{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|ɑː|d|ɛ|ʃ}}) was a goddess who was incorporated into the [[ancient Egyptian religion]] in the late [[Bronze Age]]. Her name was likely developed by the Egyptians based on the [[Semitic root]] ''[[Q-D-Š]]'' meaning 'holy' or 'blessed,'<ref>Ch. Zivie-Choche, ''[https://escholarship.org/content/qt7tr1814c/qt7tr1814c.pdf Foreign Deities in Egypt]'' [in:] J. Dieleman, W. Wendrich (eds.), ''UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology'', 2011, p. 5-6</ref> attested as a title of [[El (deity)|El]] and possibly [[Athirat]] and a further independent deity in texts from [[Ugarit]].<ref>M. Krebernik, ''Qdš'' [in:] ''[http://publikationen.badw.de/en/rla/index#9862 Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie]'' vol. 11, 2008, p. 176</ref> |

||

Due to lack of clear references to Qetesh as a distinct deity in Ugaritic and other Syro-Palestinian sources, she is considered an Egyptian deity influenced by religion and iconography of [[Canaan]] by many modern researchers, rather than merely a Canaanite deity adopted by the Egyptians (examples of which include [[Reshef]] and [[Anat]]).<ref>S. L. Budin, ''[https://www.jstor.org/stable/3270523 A Reconsideration of the Aphrodite-Ashtart Syncretism]'', ''Numen'' vol. 51, no. 2, 2004, p. 100</ref><ref>I. Cornelius, ''[http://www.religionswissenschaft.uzh.ch/idd/prepublications/e_idd_qudshu.pdf Qudshu]'', ''[http://www.religionswissenschaft.uzh.ch/idd/prepublication.php Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East]'' (electronic pre-publication), p. 1: "a goddess by the name of Q. is not known in the Ugaritic or any other Syro–Palestinian texts"</ref> |

|||

The name was probably vocalized by Egyptians as, *''Qātiša'', from the [[Semitic root]] ''[[Q-D-Š]]'' meaning 'holy'. Her city of worship was [[Kadesh (Syria)|Qadesh]] in present-day Syria. |

|||

== |

== Character == |

||

The functions of Qetesh in Egyptian religion are hard to determine due to lack of direct references, but her epithets (especially the default one, "lady of heaven") might point at an astral character, and lack of presence in royal cult might mean that she was regarded as a protective goddess mostly by commoners. Known sources do not associate her with fertility or sex, and theories presenting her as a "[[Temple prostitute|sacred harlot]]" are regarded as obsolete in modern scholarship due to lack of evidence.<ref>I. Cornelius, ''[http://www.religionswissenschaft.uzh.ch/idd/prepublications/e_idd_qudshu.pdf Qudshu]'', ''[http://www.religionswissenschaft.uzh.ch/idd/prepublication.php Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East]'' (electronic pre-publication), p. 4</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

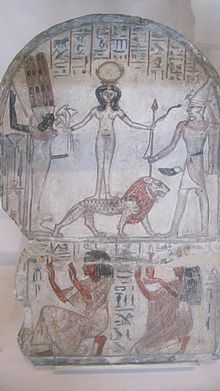

On [[:File:Stele of Qadesh upper-frame.jpg|stele]] representing the deity, Qetesh is represented as a frontal nude standing on a lion, often between [[Min (god)|Min]] of Egypt and the Canaanite warrior god [[Resheph]]. She holds a snake in one hand and a bouquet of [[Nymphaea caerulea|lotus flowers]] in the other as symbols of [[Creation myth|creation]]. |

|||

Association with [[Hathor]] may be seen in imagery as well. |

|||

Her epithets include "Mistress of All the Gods", "Lady of the Stars of Heaven", "Beloved of [[Ptah]]", "Great of magic, mistress of the stars", and "[[Eye of Ra]], without her equal".<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.matrifocus.com/LAM07/spotlight.htm|title=The "Holy One" by Johanna Stuckey|website=www.matrifocus.com|access-date=19 March 2018|archive-date=31 January 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080131132738/http://www.matrifocus.com/LAM07/spotlight.htm|url-status=dead}}</ref> A connection with Ptah or Ra evident in her epithets is also known from Egyptian texts about Anat and Astarte.<ref>M. Smith, ''[https://www.academia.edu/12709064/_Athtart_in_Late_Bronze_Age_Syrian_Texts 'Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts]'' [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), ''Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite'', 2014, p. 66</ref><ref>K. Tazawa, ''Astarte in New Kingdom Egypt: Reconsideration of Her Role and Function'' [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), ''[https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/135405/1/Sugimoto_2014_Transformation_of_a_Goddess.pdf Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite]'', 2014, p. 110</ref> |

|||

Qetesh is associated with [[Anat]], [[Astarte]], and [[Asherah]]. She also has elements associated with the goddesses of [[Mycenae]], the [[Minoan civilization|Minoan]] goddesses of [[Crete]], and certain [[Kassite]] goddesses of the metals trade in tin, copper, and bronze between [[Lothal]] and [[Dilmun]]. |

|||

== Iconography == |

|||

On some versions of the Qetesh stele her register with Min and Resheph is placed over another register showing gifts being presented to ‘Anat the goddess of war and below a register listing the lands belonging to Min and Resheph. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

On a [[:File:Stele of Qadesh upper-frame.jpg|stele]] representing the deity, Qetesh is depicted as a frontal nude (an uncommon motif in Egyptian art, though not exclusively associated with her), wearing a [[Hathor]] wig and standing on a lion, between [[Min (god)|Min]] and the Canaanite warrior god [[Resheph]]. She holds a snake in one hand and a bouquet of lotus or papyrus flowers in the other.<ref>Ch. Zivie-Choche, ''[https://escholarship.org/content/qt7tr1814c/qt7tr1814c.pdf Foreign Deities in Egypt]'' [in:] J. Dieleman, W. Wendrich (eds.), ''UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology'', 2011, p. 6-7</ref><ref>I. Cornelius, ''[http://www.religionswissenschaft.uzh.ch/idd/prepublications/e_idd_qudshu.pdf Qudshu]'', ''[http://www.religionswissenschaft.uzh.ch/idd/prepublication.php Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East]'' (electronic pre-publication), p. 1</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

== Triple goddess merged into one == |

|||

Early researchers attempted to prove Qetesh was simply a form of a known Canaanite deity, rather than a fully independent goddess. [[William F. Albright]] proposed in 1939 that she was a form of the "lady of Byblos" ([[Baalat Gebal]]), while René Dussard suggested a connection to "Asherat" (e.g. the biblical [[Asherah]]) in 1941. Subsequent studies tried to find further evidence for equivalence of Qetesh and Asherah, despite dissimilar functions and symbols.<ref>S. A. Wiggins, ''[https://www.academia.edu/1307032/The_Myth_of_Asherah_Lion_Lady_and_Serpent_Goddess The Myth of Asherah: Lion Lady and Serpent Goddess]'', ''Ugarit-Forschungen'' 23, 1991, p. 384-386; 389</ref> |

|||

'''Qudshu-Astarte-Anat''' is a representation of a single goddess who is a combination of three goddesses: Qetesh ([[Asherah|Athirat, Asherah]]), [[Astarte]], and [[Anat]]. It was a common practice for Canaanites and Egyptians to merge different deities through a process of [[syncretism]], thereby turning them into one single entity. The "Triple-Goddess Stone", once owned by Winchester College, shows the goddess Qetesh with the inscription "Qudshu-Astarte-Anat", displaying their association as being one goddess, and Qetesh (Qudshu) in place of Athirat. Qadshu is used as an epithet of [[Asherah#In Ugarit|Athirat]], [[Mother goddess|the Great Mother Goddess]] of the [[Canaan]]ites.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.thaliatook.com/OGOD/qadshu.html|title=Switching...|website=www.thaliatook.com|access-date=2018-03-19}}</ref> |

|||

The arguments presenting Qetesh and Asherah as the same goddess rely on the erroneous notion that Asherah, [[Astarte]] and [[Anat]] were the only three prominent goddesses in the religion of ancient [[Levant]], and formed a trinity.<ref>S. A. Wiggins, ''[https://www.academia.edu/1307032/The_Myth_of_Asherah_Lion_Lady_and_Serpent_Goddess The Myth of Asherah: Lion Lady and Serpent Goddess]'', ''Ugarit-Forschungen'' 23, 1991, p. 387</ref> However, while Ashtart (Astarte) and Anat were closely associated with each other in [[Ugarit]], in Egyptian sources, and elsewhere,<ref>M. Smith, ''[https://www.academia.edu/12709064/_Athtart_in_Late_Bronze_Age_Syrian_Texts 'Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts]'' [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), ''Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite'', 2014, p. 49-51</ref><ref>G. Del Olme Lete, ''[https://www.academia.edu/4583174/2013_KTU_1_107_A_miscellany_of_incantations_against_snakebite KTU 1.107: A miscellany of incantations against snakebite]'' [in] O. Loretz, S. Ribichini, W. G. E. Watson, J. Á. Zamora (eds), ''Ritual, Religion and Reason. Studies in the Ancient World in Honour of Paolo Xella'', 2013, p. 198</ref> there is no evidence for conflation of Athirat and Ashtart, nor is Athirat associated closely with Ashtart and Anat in Ugaritic texts.<ref>S. A. Wiggins, ''[https://www.academia.edu/1307031/A_Reassessment_of_Asherah_With_Further_Considerations_of_the_Goddess A Reassessment of Asherah: With Further Considerations of the Goddess]'', 2007, p. 57, footnote 124; see also p. 169</ref> The concept of Athirat, Anat and Ashtart as a trinity and the only prominent goddesses in the entire region (popularized by authors like [[Tikva Frymer-Kensky]]) is modern and ignores the large role of other female deities, for example [[Shapash]], in known texts, as well as the fact El appears to be the deity most closely linked to Athirat in primary sources.<ref>S. A. Wiggins, ''[https://www.academia.edu/17830631/A_Reassessment_of_Tikva_Frymer_Kenskys_Asherah A Reassessment of Tikva Frymer-Kensky's Asherah]'' [in:] R. H. Bael, S. Halloway, J. Scurlock, ''In the Wake of Tikva Frymer-Kensky'', 2009, p. 174</ref><ref>S. A. Wiggins, ''[https://www.academia.edu/1307034/Shapsh_Lamp_of_the_Gods Shapsh, Lamp of the Gods]'' [in:] N. Wyatt (ed.), ''Ugarit, religion and culture: proceedings of the International Colloquium on Ugarit, Religion and Culture, Edinburgh, July 1994; essays presented in honour of Professor John C. L. Gibson'', 1999, p. 327</ref> One of the authors relying on the Anat-Ashtart-Athirat trinity theory is Saul M. Olyan (author of ''Asherah and the Cult of Yahweh in Israel'') who calls the Qudshu-Astarte-Anat plaque "a triple-fusion hypostasis", and considers Qudshu to be an epithet of Athirat by a process of elimination, for Astarte and Anat appear after Qudshu in the inscription.<ref>''The Ugaritic Baal cycle: Volume 2'' by Mark S. Smith, page 295</ref><ref>''The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts'' by Mark S. Smith - Page 237</ref> |

|||

Religious scholar Saul M. Olyan (author of ''Asherah and the Cult of Yahweh in Israel'') calls the representation on the Qudshu-Astarte-Anat plaque "a triple-fusion hypostasis", and considers Qudshu to be an epithet of Athirat by a process of elimination, for Astarte and Anat appear after Qudshu in the inscription.<ref>''The Ugaritic Baal cycle: Volume 2'' by Mark S. Smith, page 295</ref><ref>''The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts'' by Mark S. Smith - Page 237</ref> |

|||

Modern [[egyptologists]], such as Christiane Zivie-Coche, do not consider Qetesh to be a hypostasis of Anat or Astarte, but a goddess developed in Egypt possibly without a clear forerunner among Canaanite or Syrian goddesses, though given a Semitic name and associated mostly with foreign deities.<ref>Ch. Zivie-Choche, ''[https://escholarship.org/content/qt7tr1814c/qt7tr1814c.pdf Foreign Deities in Egypt]'' [in:] J. Dieleman, W. Wendrich (eds.), ''UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology'', 2011, p. 5-6</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Among the epithets used for this deity, Qetesh is called "Mistress of All the Gods", "Lady of the Stars of Heaven", "Beloved of [[Ptah]]", "Great of magic, mistress of the stars", and "[[Eye of Ra]], without her equal".<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.matrifocus.com/LAM07/spotlight.htm|title=The "Holy One" by Johanna Stuckey|website=www.matrifocus.com|access-date=2018-03-19}}</ref> |

|||

== In popular culture == |

== In popular culture == |

||

Qetesh is the name given to the [[Goa'uld]] that once possessed [[Vala Mal Doran]], a recurring and then regular character in Seasons 9 and 10, respectively of the science fiction television series ''[[Stargate SG-1]]''. |

Qetesh is the name given to the [[Goa'uld]] that once possessed [[Vala Mal Doran]], a recurring and then regular character in Seasons 9 and 10, respectively of the science fiction television series ''[[Stargate SG-1]]''. |

||

Qetesh is also the name used in ''[[The Sarah Jane Adventures]]'' episode ''[[Goodbye, Sarah Jane Smith]]'', and confirmed to be the humanoid species (also known as "soul-stealers") of Ruby White (the episode's villain) who feeds off excitement and heightened emotion and have stomachs that live outside their bodies. |

|||

Moreover is Qadesh, also called Qwynn, a character in Holly Roberds' fantasy novel "Bitten by Death", published in 2021. |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

* [[Shala]], a Mesopotamian goddess also depicted as nude and associated with the sky |

|||

* [[Cybele]] |

|||

* [[Queen of Heaven (Antiquity)]] |

|||

* [[Astarte]] |

|||

* [[Aicha Kandicha]] |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

| Line 49: | Line 53: | ||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

{{Commons category}} |

{{Commons category}} |

||

* Johanna Stuckey, [http://www.matrifocus.com/LAM07/spotlight.htm The "Holy One"], MatriFocus, 2007 |

|||

{{Middle Eastern mythology}} |

{{Middle Eastern mythology}} |

||

| Line 57: | Line 60: | ||

[[Category:Egyptian goddesses]] |

[[Category:Egyptian goddesses]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Phoenician mythology]] |

|||

[[Category:West Semitic goddesses]] |

[[Category:West Semitic goddesses]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Stellar goddesses]] |

||

[[Category:Asherah]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[ca:Llista de personatges de la mitologia egípcia#Q]] |

[[ca:Llista de personatges de la mitologia egípcia#Q]] |

||

Revision as of 23:20, 13 January 2024

| Qetesh | |

|---|---|

heavenly goddess | |

A digital collage showing an image of Qetesh together with hieroglyphs taken from a separate Egyptian relief (the 'Triple Goddess stone') | |

| Symbol | Lion, snake, a bouquet of papyrus or Egyptian lotus, Hathor wig |

| Parents | Ptah or Ra[1] |

| Deities of the ancient Near East |

|---|

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

Qetesh (also Qodesh, Qadesh, Qedesh, Qetesh, Kadesh, Kedesh, Kadeš or Qades /ˈkɑːdɛʃ/) was a goddess who was incorporated into the ancient Egyptian religion in the late Bronze Age. Her name was likely developed by the Egyptians based on the Semitic root Q-D-Š meaning 'holy' or 'blessed,'[2] attested as a title of El and possibly Athirat and a further independent deity in texts from Ugarit.[3]

Due to lack of clear references to Qetesh as a distinct deity in Ugaritic and other Syro-Palestinian sources, she is considered an Egyptian deity influenced by religion and iconography of Canaan by many modern researchers, rather than merely a Canaanite deity adopted by the Egyptians (examples of which include Reshef and Anat).[4][5]

Character

The functions of Qetesh in Egyptian religion are hard to determine due to lack of direct references, but her epithets (especially the default one, "lady of heaven") might point at an astral character, and lack of presence in royal cult might mean that she was regarded as a protective goddess mostly by commoners. Known sources do not associate her with fertility or sex, and theories presenting her as a "sacred harlot" are regarded as obsolete in modern scholarship due to lack of evidence.[6]

Her epithets include "Mistress of All the Gods", "Lady of the Stars of Heaven", "Beloved of Ptah", "Great of magic, mistress of the stars", and "Eye of Ra, without her equal".[7] A connection with Ptah or Ra evident in her epithets is also known from Egyptian texts about Anat and Astarte.[8][9]

Iconography

On a stele representing the deity, Qetesh is depicted as a frontal nude (an uncommon motif in Egyptian art, though not exclusively associated with her), wearing a Hathor wig and standing on a lion, between Min and the Canaanite warrior god Resheph. She holds a snake in one hand and a bouquet of lotus or papyrus flowers in the other.[10][11]

Origin

Early researchers attempted to prove Qetesh was simply a form of a known Canaanite deity, rather than a fully independent goddess. William F. Albright proposed in 1939 that she was a form of the "lady of Byblos" (Baalat Gebal), while René Dussard suggested a connection to "Asherat" (e.g. the biblical Asherah) in 1941. Subsequent studies tried to find further evidence for equivalence of Qetesh and Asherah, despite dissimilar functions and symbols.[12]

The arguments presenting Qetesh and Asherah as the same goddess rely on the erroneous notion that Asherah, Astarte and Anat were the only three prominent goddesses in the religion of ancient Levant, and formed a trinity.[13] However, while Ashtart (Astarte) and Anat were closely associated with each other in Ugarit, in Egyptian sources, and elsewhere,[14][15] there is no evidence for conflation of Athirat and Ashtart, nor is Athirat associated closely with Ashtart and Anat in Ugaritic texts.[16] The concept of Athirat, Anat and Ashtart as a trinity and the only prominent goddesses in the entire region (popularized by authors like Tikva Frymer-Kensky) is modern and ignores the large role of other female deities, for example Shapash, in known texts, as well as the fact El appears to be the deity most closely linked to Athirat in primary sources.[17][18] One of the authors relying on the Anat-Ashtart-Athirat trinity theory is Saul M. Olyan (author of Asherah and the Cult of Yahweh in Israel) who calls the Qudshu-Astarte-Anat plaque "a triple-fusion hypostasis", and considers Qudshu to be an epithet of Athirat by a process of elimination, for Astarte and Anat appear after Qudshu in the inscription.[19][20]

Modern egyptologists, such as Christiane Zivie-Coche, do not consider Qetesh to be a hypostasis of Anat or Astarte, but a goddess developed in Egypt possibly without a clear forerunner among Canaanite or Syrian goddesses, though given a Semitic name and associated mostly with foreign deities.[21]

In popular culture

Qetesh is the name given to the Goa'uld that once possessed Vala Mal Doran, a recurring and then regular character in Seasons 9 and 10, respectively of the science fiction television series Stargate SG-1.

Qetesh is also the name used in The Sarah Jane Adventures episode Goodbye, Sarah Jane Smith, and confirmed to be the humanoid species (also known as "soul-stealers") of Ruby White (the episode's villain) who feeds off excitement and heightened emotion and have stomachs that live outside their bodies.

Moreover is Qadesh, also called Qwynn, a character in Holly Roberds' fantasy novel "Bitten by Death", published in 2021.

See also

- Shala, a Mesopotamian goddess also depicted as nude and associated with the sky

- Queen of Heaven (Antiquity)

References

- ^ I. Cornelius, Qudshu, Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East (electronic pre-publication), p. 1, 4

- ^ Ch. Zivie-Choche, Foreign Deities in Egypt [in:] J. Dieleman, W. Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2011, p. 5-6

- ^ M. Krebernik, Qdš [in:] Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie vol. 11, 2008, p. 176

- ^ S. L. Budin, A Reconsideration of the Aphrodite-Ashtart Syncretism, Numen vol. 51, no. 2, 2004, p. 100

- ^ I. Cornelius, Qudshu, Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East (electronic pre-publication), p. 1: "a goddess by the name of Q. is not known in the Ugaritic or any other Syro–Palestinian texts"

- ^ I. Cornelius, Qudshu, Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East (electronic pre-publication), p. 4

- ^ "The "Holy One" by Johanna Stuckey". www.matrifocus.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ M. Smith, 'Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 66

- ^ K. Tazawa, Astarte in New Kingdom Egypt: Reconsideration of Her Role and Function [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 110

- ^ Ch. Zivie-Choche, Foreign Deities in Egypt [in:] J. Dieleman, W. Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2011, p. 6-7

- ^ I. Cornelius, Qudshu, Iconography of Deities and Demons in the Ancient Near East (electronic pre-publication), p. 1

- ^ S. A. Wiggins, The Myth of Asherah: Lion Lady and Serpent Goddess, Ugarit-Forschungen 23, 1991, p. 384-386; 389

- ^ S. A. Wiggins, The Myth of Asherah: Lion Lady and Serpent Goddess, Ugarit-Forschungen 23, 1991, p. 387

- ^ M. Smith, 'Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 49-51

- ^ G. Del Olme Lete, KTU 1.107: A miscellany of incantations against snakebite [in] O. Loretz, S. Ribichini, W. G. E. Watson, J. Á. Zamora (eds), Ritual, Religion and Reason. Studies in the Ancient World in Honour of Paolo Xella, 2013, p. 198

- ^ S. A. Wiggins, A Reassessment of Asherah: With Further Considerations of the Goddess, 2007, p. 57, footnote 124; see also p. 169

- ^ S. A. Wiggins, A Reassessment of Tikva Frymer-Kensky's Asherah [in:] R. H. Bael, S. Halloway, J. Scurlock, In the Wake of Tikva Frymer-Kensky, 2009, p. 174

- ^ S. A. Wiggins, Shapsh, Lamp of the Gods [in:] N. Wyatt (ed.), Ugarit, religion and culture: proceedings of the International Colloquium on Ugarit, Religion and Culture, Edinburgh, July 1994; essays presented in honour of Professor John C. L. Gibson, 1999, p. 327

- ^ The Ugaritic Baal cycle: Volume 2 by Mark S. Smith, page 295

- ^ The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts by Mark S. Smith - Page 237

- ^ Ch. Zivie-Choche, Foreign Deities in Egypt [in:] J. Dieleman, W. Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2011, p. 5-6