Second Punic War

The Second Punic War was from 218 BC. Until 202 BC Between the Romans and the Carthaginians ( Latin Punians ). The Carthaginian general Hannibal from the Barkid dynasty brought Rome to the brink of defeat through a series of tactically skilful battles. The Romans then went on to a long war of attrition and successfully carried the war to Carthaginian territory. Finally they finally won the battle of Zama under their general Scipio the Elder . The war finally decided the struggle between the two cities for dominance in the Mediterranean region in favor of Rome.

Sources

Due to the complete destruction of Carthage in the Third Punic War in 146 BC. There are no historical sources describing the course of the war and its background from a Carthaginian perspective. Historians can therefore only rely on works by Greek and Roman authors of antiquity - especially Polybius and Livy - and must interpret them carefully: the great defeats that the Roman Empire suffered in the course of the Second Punic War were interpreted in this way by Roman historians that they fundamentally did not question the Roman political and social order. Even in the catastrophic defeats, Rome's greatness had to be proven and a scapegoat found. This is especially true of the devastating defeat Rome suffered at the Battle of Cannae .

Outbreak of war

After the First Punic War , Carthage had to cede his possessions in Sicily and later also in Sardinia and Corsica to Rome. To compensate for this loss, the North African city had expanded its sphere of influence on the Iberian Peninsula. The Barkid family was particularly active in this colonization enterprise : Hamilkar Barkas and his sons Hannibal and Hasdrubal Barkas as well as the son-in-law Hasdrubal the Beautiful . Until the outbreak of the Second Punic War, it was primarily Hasdrubal Barkas who established an independent power base for his family. He achieved military and diplomatic sovereignty over several Iberian tribes. In 227 BC He founded the city of Carthago Nova ( Cartagena ), which subsequently functioned as the center of Barcid power in Spain.

The historian Polybios , who was often friendly to Rome, assumes that the Barkids had a head against Rome in their policy on Spain. Carthage won the new province primarily for a war of revenge against Rome. However, the so-called Ebro Treaty , which Hasdrubal signed in 226 BC , speaks decisively against it . BC with the Romans. In this a Spanish river called the Iber (possibly the Ebro ) was established as the border between the Roman and Carthaginian spheres of interest in Spain. Various historical works about Hannibal that took a pro-Carthaginian standpoint, however, have been lost. These include the works of Sosylus and Silenus from Kaleakte .

One can only speculate about the Roman interest in a renewed war with the Puniers: Presumably there was primarily a special interest in the prosperous Iberian Peninsula and not in a large-scale war in the entire western Mediterranean. The Romans used a diplomatic strategy similar to that used in the First Punic War, using a single city as an occasion for war. The city of Sagunt was far south of the Ebro and thus in the area assigned to Carthage. When the Carthaginian general Hannibal, who had succeeded his murdered brother-in-law Hasdrubal, set out to conquer Sagunt, Roman envoys tried to forbid him to do so: the city was allegedly allied with Rome. In fact, during the eight month long siege, the Romans did nothing in favor of their supposed allies and waited until Sagunto in 219 BC. Had fallen. Hannibal knew that Rome was the protective power of the Saguntins, but he had no choice but to conquer the city, as the Saguntins had repeatedly attacked Carthaginian territory in recent years. Now Rome threatened the Punis with war if Hannibal was not handed over to them. The councilors of Carthage refused this request, whereupon the Roman declaration of war followed.

Course of war

From the crossing of the Ebro to the Battle of Cannae (218–216 BC)

Saguntum - Lilybaeum II - Rhone - Ticinus - Trebia - Cissa - Lake Trasimeno - Ager Falernus - Geronium - Cannae - Nola I - Nola II - Ibera - Cornus - Nola III - Beneventum I - Syracuse - Tarentum I - Capua I - Beneventum II - Silarus - Herdonia I - Upper Baetis - Capua II - Herdonia II - Numistro - Asculum - Tarentum II - New Carthage - Baecula - Grumentum - Metaurus - Ilipa - Crotona - Large fields - Cirta - Zama

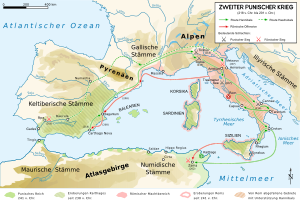

Compared to the beginning of the last war, the military requirements of the two adversaries had in fact reversed: Rome was now the dominant maritime power, while Carthage had become the land power in Spain. At that time the war had ultimately been decided by the stronger Roman fleet, so that Hannibal was faced with a dilemma, as nothing in this imbalance had changed. Therefore, he decided on an offensive strategy in which this disadvantage did not come into play: In order to forestall an attack on Spain or North Africa, Hannibal planned the invasion of Italy.

Hannibal negotiated beforehand with the Celtic tribes, whose territory he had to cross in order to penetrate to Italy. Nevertheless, the train across the Pyrenees was marked by numerous battles against the native tribes. For the most part, Hannibal was able to convince the Celts in southern France that he would not regard them as opponents, only on the Rhone did a Celtic tribe offer brief and futile resistance. Finally, the Carthaginians set out to cross the Alps with probably 50,000 foot soldiers, 9,000 horsemen and 37 elephants .

According to differing information from Polybios and Titus Livius, Hannibal probably crossed the Alps via the Rhone Valley and / or the Isère . The passage over the mountains was very costly for Hannibal's troops. Hostile Allobrogian tribes harassed the Carthaginians, while bad weather in the mountains resulted in losses, especially among the elephants. End of 218 BC Hannibal finally reached the Po plain . The region was shaken at that time by tribal feuds among the Celts and revolts against Rome. Hannibal managed to bind many of the tribes militarily or diplomatically to himself.

The consul and general Publius Cornelius Scipio had tried in vain to intercept Hannibal on the Rhone. So he had embarked with most of his troops to await the Carthaginians in the Po Valley. During the battle on the Ticinus River , there was a first brief battle between the troops of Hannibal and Scipios. The Romans were defeated. Hannibal moved on after the Romans and offered a battle. But Scipio hesitated, which resulted in parts of his own Celtic allies leaving the Roman army. On the Trebia River , Hannibal met the combined consular armies of Scipio and Tiberius Sempronius Longus in December . The Carthaginians achieved an overwhelming victory, while the Romans suffered heavy losses.

217 BC Chr. Hannibal moved further south. With numerous promises he tried to win Italian tribes to his side. In the battle of Lake Trasimeno , Hannibal met the legionaries under the new consul Gaius Flaminius . He surrounded the legions and the battle was lost for Rome. 15,000 Romans fell, including Flaminius. The same number of legionaries were taken prisoner. Hannibal released the captured soldiers of the Roman allies without demanding a ransom. With this he hoped to be able to persuade the Italians to overflow.

The Roman Senate initiated the election of a dictator to stop Hannibal. Was elected Fabius Maximus , the losmarschierte with two legions. Maximus had learned from the fate of his predecessors and avoided a battle. He wanted to wear Hannibal down by waiting. The Carthaginian moved on towards Campania in order to set up winter quarters on the Volturnus River (now Volturno ). Here Maximus wanted to force the enemy to battle. But Hannibal escaped with a ruse and moved to Gerunium. Here he built his winter quarters.

In advance, the Romans attacked the Punians under their Magister equitum Marcus Minucius Rufus and won smaller battles. Meanwhile the mood in Rome had turned against the dictator, who was ridiculed as a cunctator (procrastinator) . The Roman people's assembly was blinded by Rufus' insignificant successes and therefore unconstitutionally appointed him second dictator. The election caused disagreements between the two generals. When Hannibal broke out of his quarters and pressed Rufus' troops, he was threatened with annihilation. But Maximus managed to rush to Rufus' aid, whereupon Hannibal returned to his camp. However, after his defeat, Rufus voluntarily moved back to the second rank. The dictators' term of office ended a little later.

216 BC Hannibal wanted to force the Romans to battle and therefore captured the magazines of the city of Cannae . In the meantime Rome had assembled a new, huge army. The two consuls Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro had the task of daring a decisive battle against Hannibal. They commanded about 80,000 foot soldiers and 6,000 horsemen, while Hannibal only had 40,000 infantrymen and 10,000 cavalrymen. However, the different tactics of their two generals were problematic for the Roman army: while Paullus advised careful action against the Punians, Varro urged an offensive approach.

On August 2nd the battle of Cannae took place . The Romans attacked the Carthaginian center, whereupon Hannibal let the middle of his infantry slowly retreat, so that the Roman foot soldiers were finally surrounded in a crescent shape. At the same time, the Carthaginian cavalry outstripped the Roman cavalry, destroyed them and now stood in the rear of the opposing infantry. The Romans, who were still outnumbered, were surrounded and crowded together in a very small space. The Romans were defeated and the consul Paullus was killed in battle. Almost 50,000 Roman legionaries were killed in the battle. Cannae went down in war history as a prime example of an encircling battle and is still a subject of instruction at military academies today.

Hannibal's war goal was to reduce Rome to a Latin middle power. To do this, however, it was first necessary to destroy Rome's strong alliance system. That is why Hannibal did not march against Rome after the triumph of Cannae, for which his military capacities would hardly have been sufficient. Again the prisoners of war of the Roman allies were released. In fact, some communities subsequently converted to Hannibal, but the core of the Roman sphere of influence was retained. The decisive factor was that Rome was at no point willing to negotiate peace with Hannibal. It soon turned out that despite his three great victories on the battlefield, Hannibal had few options.

From the battle of Cannae to the fall of Capua (216–211 BC)

The most important city that passed to Hannibal after Cannae was Capua . In the following years he was busy with numerous skirmishes and sieges to undermine the Roman influence in Italy. Important cities such as Naples and Nola remained loyal to the Romans and prevented Hannibal from establishing a closed area of power in southern Italy.

However, the Carthaginian general was able to achieve some diplomatic successes: He concluded in 215 BC. An alliance with the Macedonian king Philip V , which should prove to be ineffective. In the mighty Greek city of Syracuse in Sicily, after the death of Hieron II, there was a change in favor of Carthage. Hieron's grandson Hieronymous received the promise of rule over the whole island from the Puners. Furthermore, in North Africa the East Numid king Massinissa sided with Carthage, while his West Numid rival Syphax allied himself with Rome.

After its successes in Italy, Carthage tried to regain a foothold in its old possessions: In Sardinia, however, the Carthaginians suffered a devastating defeat. In order to come to the aid of the new ally Syracuse, strong Carthaginian forces landed on Hannibal's advice in Sicily, but the Roman troops under Marcus Claudius Marcellus prevailed and conquered in 212 BC. BC Syracuse (this victory gained additional notoriety through the killing of Archimedes ).

Even before Hannibal's crossing of the Alps, Publius Cornelius Scipio had sent his brother Gnaeus with an army to northern Spain. After landing in Empúries , he was able to establish himself north of the Ebro. After the lost battle of the Trebia, Publius brought reinforcements to his brother. On this one point, Hannibal's strategy was not fully successful, as the Barcidian base in Spain was now threatened by Roman troops. Until 211 BC BC the two Scipions were able to expand the Roman influence to the south. Then Hasdrubal Barkas managed to separate the armies of the Romans and defeat them in two successive battles, in which Publius and Gnaeus were killed. Despite this success, Hasdrubal did not see himself in a position to completely drive the Romans out of Spain.

212 BC Hannibal succeeded in winning Taranto for his side. The city fortress was still held by the Romans, so that Hannibal was forced to a protracted siege. Meanwhile his allies in Capua were surrounded by Roman troops. Torn between the two locations, Hannibal finally launched a mock attack on Rome to save Capua (" Hannibal ante portas "). However, he could not save the city from the fall, which had serious political consequences for him: Hannibal had stood up to end Rome's influence on the Italians, and was now unable to protect his most important ally. This was rightly viewed by ancient historians as the peripetia (turnaround) of war. In any case, the Romans then reduced their contingents.

From the fall of Capuas to the Battle of Zama (211–202 BC)

Hannibal did not give up his cause on the Italian arena and received new funds and troops from Carthage. In the following years he moved across southern Italy, where there were numerous skirmishes and sieges. Neither side was able to gain a decisive advantage.

In Spain, the son of the same name of the fallen Publius Cornelius Scipio had taken command of the remaining Roman troops. The 25-year-old, who was later to bear the honorary name Scipio Africanus Major , was given the powers of a consul, although he had never held a comparable office. He succeeded in 209 BC. To conquer the Carthaginian regional capital Carthago Nova (Cartagena) in one stroke.

After all, Hasdrubal Barkas had managed to cross the Alps like his brother Hannibal in order to bring this urgently needed supplies. The unification of the Carthaginian armies failed due to Hasdrubal's tactical mistakes. He lost valuable time due to an unnecessary siege of the city of Placenta , today's Piacenza. In addition, the messengers with whom he communicated the plan to unite the two armies to his brother fell into the hands of the Romans. After a seven-day forced march, the Roman consul Claudius Nero presented Hasdrubal's army in 207 BC. In the battle of Metaurus Hasdrubal lost his life and Hannibal lost his last hope of turning the fortunes of war in his favor. Hannibal's head was sent to his army camp .

The young Scipio finally achieved 206 BC. A decisive victory in Spain over Hannibal's youngest brother Mago, which forced him to give up the Iberian Peninsula in the following year. The Numidian king Massinissa then turned against his previous Carthaginian allies. Scipio decided to invade North Africa and defeated the Carthaginians in a field battle. They now called their general Hannibal back from Italy, who was still undefeated in open battle.

Scipio advanced further on Carthage and 202 BC. His army and the Hannibals met at Zama . The Carthaginians had more infantrymen than the Romans, but after the defection of the Massinissa they lacked the necessary cavalry with which Hannibal could achieve his great victories. So the role of Carthage as a great power ended in the Battle of Zama .

The War in Iberia (218–206 BC)

After an unsuccessful attempt to intercept Publius Cornelius Scipios on the Rhone, the latter sent his brother Gnaeus with part of the army to Iberia. There he landed at Emporion, north of the Ebro. He spent the next weeks and months building the area between the Ebro and the Pyrenees into a base for future operations in southern Iberia. The Iberian tribes living there assured him of their support very early on. Soon there was the first battle with Hanno, the Carthaginian commander of the areas north of the Ebro. In one battle Gnaeus was able to defeat Hanno, which resulted in a fall of many other Iberian tribes north of the Ebros.

During the winter, Hasdrubal received support from Africa. The next year he marched north to face Gnaeus. However, he did not agree to a land battle and sent his ships to the mouth of the Ebro, where there was a battle with the Carthaginian fleet. The Romans won a great victory. Around 25 of the 40 Carthaginian ships were sunk or fell into the hands of the Romans.

In 217 BC The Roman Senate sent Gnaeus' brother Publius Cornelius Scipio with 20 ships to Iberia. In the years that followed, the Scipions managed to convince other tribes to overflow, but they did not undertake any major offensives south of the Ebro until the year 211, simply because their army was outnumbered by the Carthaginians. In the winter of 212/11 BC The armies of the two brothers were reinforced by 20,000 Celtiberians. With these new troops, the Scipions wanted to carry out large operations south of the Ebros. However, the brothers made the mistake of dividing their armies. So Gnaeus led a third of the army against Hasdrubal Barkas and Publius the rest against Mago and Hasdrubal, the son of Gisko. So the two Romans were greatly inferior to their Carthaginian opponents. Publius not only lost a large part of his army, but also his life in the following battle against the Carthaginians and their Iberian allies. When this message reached Gnaeus, many of his Iberian allies deserted and he had to withdraw. However, he was overtaken by the Carthaginians and experienced the same fate as his brother. So the Punians were able to recapture their lost territories south of the Ebro in the coming weeks.

In 210 BC Therefore the son of the same name Publius Cornelius Scipios took over the command in Iberia. His task was to instill new courage in the completely demotivated legionaries and to rebuild the base of the Romans north of the Ebro. Scipio's spies reported that the capital of Punic Iberia, New Carthage, was only guarded by a rather small garrison. In addition, the nearest Carthaginian army was about 10 days' march from the capital. So Scipio decided to attack the city that promised rich booty. Within seven days he was able to get from the mouth of the Ebro to New Carthage and 209 BC. To conquer the city in a hard fight.

A year later he was able to defeat Hasdrubal, Hannibal's brother, in a battle, who then moved to Italy to support his brother.

At Ilipa it happened 206 BC. For the decisive battle between the Carthaginians and the Romans, in which the latter triumphed. After this defeat, Iberia could no longer be held by the Punians. The involvement of the Romans in Hispania was probably one of the decisive factors for the war. Not only were the forces of the Punians tied here, who would otherwise have supported Hannibal in his struggle in Italy, but the initial successes of the Romans relativized the devastating defeats in Italy to a certain extent and helped the city on the Tiber to continue the war motivate.

Table overview

Various questions should be answered from the following table:

- How could the sometimes enormous losses suffered by the warring parties be compensated? Temporal events can be separated from material ones.

- What role did the luck of war and successful alliance politics play ? Loss figures can be presented separately from military success.

- When is the time factor decisive with the respective situation of the warring parties in the course of the war? An evaluation of the results allows classification in a war goal .

- One can even deduce from the data that there was at all times a sea-based superiority of the Roman over the Punic armed forces.

- (Empty cells indicate unresolved issues.)

| Year before Chr. |

Name of the battle | Art | Roman troops |

Roman fallen |

Roman prisoners |

Punic troops |

Punic Fallen |

Punic prisoners |

winner | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 218 | Saguntum | siege | lots | lots | few | no | Carthage | crucial | ||

| 218 | Lilybaeum II | Naval battle | no | 1700 | Rome | crucial | ||||

| 218 | Rhone | Field battle | 46000 | no | Carthage | important | ||||

| 218 | Ticinus | Field battle | 4000 | few | 6000 | few | no | Carthage | low | |

| 218 | Trebia | Field battle | 43000 | 20000 | 26000 | no | Carthage | considerable | ||

| 218 | Cissa | Field battle | 22000 | no | 11500 | 6000 | 2000 | Rome | crucial | |

| 218 | Lake Trasimeno | Field battle | 40000 | 15000 | 15000 | 30000 | 1500 | no | Carthage | considerable |

| 217 | Ager Falernus | Field battle | 4000 | more than 1000 | a few thousand | few | no | Carthage | low | |

| 217 | Geronium | Field battle | 40000 | 50000 | few | - patt - | low | |||

| 216 | Cannae | Field battle | 86000 | 70000 | 10,000 | 50000 | 8000 | no | Carthage | considerable |

| 216 | Nola I | siege | few | no | Rome | low | ||||

| 215 | Nola II | siege | few | no | Rome | low | ||||

| 215 | Ibera | Field battle | 33000 | lots | no | 29000 | Rome | important | ||

| 215 | Cornus | Field battle | 20000 | no | 16500 | many many | Rome | crucial | ||

| 214 | Nola III | Field battle | no | lots | Rome | important | ||||

| 214 | Beneventum I | Field battle | 18000 | no | 18200 | more than 16,000 | Rome | considerable | ||

| 214 | Syracuse | siege | no | lots | lots | Rome | important | |||

| 212 | Tarentum I | siege | 5000 | almost all | 10,000 | few | Carthage | important | ||

| 212 | Capua I | siege | 40000 | 30000 | no | Carthage | important | |||

| 212 | Beneventum II | Field battle | few | no | Rome | low | ||||

| 212 | Silarus | Field battle | 15000 | 14000 | 1000 | 26000 | a few thousand | no | Carthage | considerable |

| 212 | Herdonia I | Field battle | 18000 | 15-16 thousand | 25,000 | very few | no | Carthage | considerable | |

| 211 | Upper Baetis | Field battle | 53000 | more than 20,000 | 48500 | no | Carthage | low | ||

| 211 | Capua II | Field battle | few | no | Rome | important | ||||

| 210 | Herdonia II | Field battle | 20000 | 12000 | 25,000 | few | no | Carthage | important | |

| 210 | Numistro | Field battle | - patt - | low | ||||||

| 209 | Asculum | Field battle | 20000 | 3000 | - patt - | important | ||||

| 209 | Tarentum II | siege | very few | no | lots | Rome | important | |||

| 209 | New Carthage | siege | 35000 | no | 25,000 | 6000 | 10,000 | Rome | important | |

| 208 | Baecula | Field battle | 35000 | no | 25,000 | 6000 | 10,000 | Rome | important | |

| 207 | Grumentum | Field battle | 500 | no | 8000 | 700 | Rome | low | ||

| 207 | Metaurus | Field battle | 30000 | 20000 | no | 35-40 thousand | 20000 | Rome | important | |

| 206 | Ilipa | Field battle | 48000 | no | 74000 | Rome | crucial | |||

| 204 | Crotona | Field battle | 4 legions | - patt - | low | |||||

| 203 | Big fields | Field battle | 30000 | no | 30000 | almost all | Rome | considerable | ||

| 203 | Cirta | Field battle | no | Rome | important | |||||

| 202 | Zama | Field battle | 42700 | 1500 | no | 53000 | 20000 | 15000 | Rome | crucial |

Conclusion: The 5 significant victories of Carthage can not make up for the 5 decisive victories of Rome , even if the victories of Carthage may seem clearer. This is mainly due to the logistical superiority of Rome from the beginning of the dispute. (see → Saguntum , Lilybaeum II and Sea Authority in general).

Peace treaty

After the defeat, Hannibal advised the Carthaginian council to start peace negotiations. On behalf of the Roman Senate, Scipio led the negotiations that led to the peace dictate of 201 BC. BC: Carthage had to surrender the war fleet except for ten triremes and abandon all war elephants. It lost all possessions outside of North Africa and had to pay contributions of 10,000 talents of silver (360 tons of silver) within 50 years. As a show of force, Scipio had hundreds of Carthaginian ships burned at the gates of the city.

Most serious for the political future of the Punic State turned out to be the prohibition of independent warfare without the permission of Rome. At the same time Carthage had to recognize the independence of the Kingdom of Numidia under the Roman ally Massinissa, which in future could take action against its neighbors at will. The Punians had lost their foreign policy sovereignty and were henceforth limited to the status of a middle power . In addition, Carthage had to make an alliance with Rome and undertake to provide war assistance to the Romans if necessary.

Fifty-five years later, the Carthaginian state ended in the Third Punic War .

literature

- Sir Nigel Bagnall: Rome and Carthage - The Battle for the Mediterranean . Siedler, Berlin 1995, ISBN 3-88680-489-5 .

- Ursula Händl-Sagawe: The beginning of the 2nd Punic War. A historical-critical commentary on Livius Book 21. (= Munich works on ancient history. 9). Ed. Maris, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-925801-15-4 . (At the same time: Munich, Univ., Diss., 1992: A historical-critical commentary on Livius, Book 21 )

- Herbert Heftner : The Rise of Rome. From the Pyrrhic War to the fall of Carthage (280–146 BC). 2nd, improved edition. Pustet, Regensburg 2005, ISBN 3-7917-1563-1 .

- Alfred Klotz : Appian's representation of the Second Punic War . Schöningh, Paderborn 1936.

- Anne Kubler: La mémoire culturelle de la deuxième guerre punique (= Swiss contributions to classical studies. Volume 45). Schwabe, Basel 2018, ISBN 978-3-7965-3770-7 (on the after-effects in cultural memory).

- Karl-Heinz Schwarte: The outbreak of the Second Punic War - legal question and tradition. (= Historia individual writings. 43). Steiner, Wiesbaden 1983, ISBN 3-515-03655-5 . (At the same time: Bonn, Univ., Habil.-Schr., 1980/81)

- Jakob Seibert : Hannibal . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1993, ISBN 3-534-12029-9 (comprehensive presentation).

- Klaus Zimmermann : Carthage - the rise and fall of a great power . Theiss-Verlag, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8062-2281-4 .

- Klaus Zimmermann: Rome and Carthage . 2nd, revised edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2009, ISBN 978-3-534-23008-2 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Pedro Barceló : Short Roman History . Special edition, 2nd, bibliographically updated edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2012, ISBN 978-3-534-25096-7 , p. 29.

- ^ Zimmermann, Klaus .: Carthage: The rise and fall of a great power . Knowledge Buchges, [Darmstadt] 2010, ISBN 978-3-534-22790-7 .