Empuries

Empúries ( ancient Greek Ἐμπόριον Emporion , Latin Emporiae , Spanish Ampurias ) was an ancient Greek ( Ionian ) colony in what is now the Catalan province of Girona in the extreme northeast of Spain . It went on a around 600 BC. A trading post ( Emporion ) and a settlement founded later.

The visible parts are accessible as an archaeological park with an attached museum ( Museu d'Arquelogia de Catalunya-Empúries ), the so-called pier of the Greek complex is located directly on a beach. The city consisted of three parts in antiquity, the earliest “old town” ( Palaiapolis ) on the hill of Sant Martí d'Empúries, the Greco- Iberian new town ( Neapolis ) and the Roman municipal city . Since Sant Martí was also settled in the Middle Ages and modern times, the history of the city stretches from the Iron Age with a springless phase in the early Middle Ages to the present day. The city experienced a heyday in the Hellenistic period and in the early Roman Empire . In Roman times, Empúries was mentioned by numerous writers such as Livius , Polybios or the geographer Strabo as an important city and port on the Spanish Mediterranean coast .

location

The city is located 35 kilometers south of the French border in the district of L'Escala on the Gulf of Roses in Catalonia . The ruins of Empúries gave the region Empordà (Spanish: Ampurdán ) and the Marina Empuriabrava their names. The area around the Palaiapolis (old town) near today's Sant Martí d'Empúries, a suburb of L'Escala, was still an island at that time, the mouth of the River Fluvià (Latin Clodianus ) , which is further north today , was used as a natural harbor. Strabo gave the distance to the Pyrenees at about 200 stages .

The island location of Greek trading establishments is very common in the region, roughly comparable to Massilia, today's Marseille at the mouth of the Rhone , or Agde at the mouth of the Hérault . The area is surrounded by brackish waters, moors and reed seas that are typical of the Ampurdán coast. The mouth of the river below the hill of the Palaiapolis was one of the few ports on the Spanish east coast to offer protection from storms.

history

Phocean city foundation

The earliest history of the city begins with the establishment of a trading post called Emporion by Phocaeans from Massilia around 600 BC. Shortly after the founding of Massilia , other Phocean colonies such as Agde and Rhode , today's Roses , emerged in the region . They brokered trade with the Iberian inland areas and the Punic cities on the south coast of Spain and the Balearic Islands . The economic basis of these settlements was the exchange of high-quality imported products such as metal or pottery for agricultural products and ores from the interior.

In what is now Catalonia, the Greek settlers encountered a since the 6th century BC. Chr. Tangible development, the spread of the Iberian culture northwards to what is now southern France, the transition from Late Bronze Age cultures to the Iron Age . This is proven by the finds of numerous Iberian written documents, key forms of the ceramics used and preliminary stages of an urban culture. The influence of the Greek colony can be seen in the nearby Iberian oppidum of Ullastret . In addition to imported Greek ceramics, a Hellenistic city wall, a sanctuary at the highest point of the hill similar to an acropolis and an agora-like place are proven.

Together with the around 500 BC Founded Graeco-Iberian settlement Neapolis , the now Palaiapolis ("old town") called trading settlement formed the Polis Emporion, one of the westernmost foundations of the Greek colonization in the Mediterranean. Strabo reported that Iberians from the tribe of the indigenous people had settled near the Greek settlement . Iberians and Greeks later built a wall to protect them. In this way, a Greek-Iberian twin city with a common constitution emerged. A detailed account in Livius is largely identical to Strabon's information. Both reports possibly go back to a presentation by Poseidonios . They describe the development from the trading post to the city complex of the Neapolis when the city was expanded from the hill of the Palaiapolis to the south by the new city. The old town continued to exist under the new legal status and remained populated beyond the end of antiquity.

The city minted coins in the Punic coin base with the Pegasus on the reverse and the Greek legend ЕМПОРІТΩΝ (genitive). Signs of the cultural exchange with the Iberians, which was promoted by trade, were imitations of this motif on Iberian coins, on which instead of the pegasus a horse with a rider was often seen in a similar pose.

Roman Republic

Towards the end of the 3rd century BC The city in the extreme northeast of the Iberian Peninsula was the starting point of the Roman conquest. In the early days of the Second Punic War , there went there in 218 BC. The first Roman army on Spanish soil under Cn. Cornelius Scipio ashore. 210 BC The Roman reinforcement of P. Cornelius Scipio Africanus landed there .

Probably due to the merits of the residents in the Second Punic War, Empúries retained its status as a formally independent allied civitas ( urbs sociorum ) and remained an important city on the east coast of the province of Hispania citerior . During the protracted conquest of Spain by the Romans, Empúries, which was still influenced by Greece, was an important port for supplies, for example under the governorship of M. Porcius Cato in 195 BC. Above the Neapolis was on a gently rising hill in the 2nd century BC. A small Roman military station ( praesidium ), which was abandoned towards the end of the century. It was replaced by a planned Roman town in a long rectangular shape (300 × 750 m), which bore the Latin name Emporiae . The common legal status in republican times was presumably regulated as foedus aequo iure , which means that the city was on paper an equal ally of Rome. In the imperial era it is documented as a municipality .

When and in what way the legal form changed from an allied Greek city to a settlement of citizens under Latin law, can only be assumed due to a lack of written sources. Sallust reported that Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus lived in the winter of 77 BC. After the suppression of the Sertorius uprising in this area. It is conceivable that Emporiae later sided with the Pompeians in the civil war between Caesar and Pompeius and was punished for this. After the battle of Munda in 45 BC In any case, Caesar had veterans settled there, as Livy noted.

Roman Imperial Era

During the Roman Empire, the city lost its importance compared to the emerging neighboring cities such as Barcino ( Barcelona ) and the provincial capital Tarraco ( Tarragona ). From an economic point of view, Empúries offered a good port, but it was off the main trade routes such as the Strait of Bonifacio , on which Tarraconian wine, southern Spanish olive oil and garum were shipped via the shortest route to Italy. The simultaneous decline in Italian exports, such as ceramic products such as the so-called Campana ware or Terra Sigillata , from which the city had still benefited in the Republican era, illustrates the economic decline of the once important trading center. A silting up of the harbor by sediments from the Fluvià is still considered as the cause.

The decline in financial strength can already be seen in later buildings in the municipal city. Attempts were made to keep pace with the building program of neighboring cities by building an amphitheater and a palaestra on the southern city wall. However, the very simple execution of the buildings already shows that the city lacked the funds. The number of inscriptions found, especially from the middle imperial period, is small compared to other Hispanic cities. The southern portico of the forum collapsed in Flavian times and was never rebuilt. Roads and drainage canals were barely maintained. Since the high imperial era, life must have taken place more and more between ruins. Inscriptions testify that there was a vexillatio of Legio VII Gemina in the city . Small finds such as ceramics and coins point to the settlement of the planned town on the plain until the 3rd century AD. It is possible that a Franconian invasion of Spain in AD 260 led to the final abandonment of the Roman city on the plain. The latest coin was minted under Claudius Gothicus . The establishment of an early Christian church in the remains of the agora shows that the settlement continued.

Late antiquity

In late antiquity , the development of Empúries showed parallels to numerous late Roman settlements: When Vandal, Alan and Suebi warriors crossed the Pyrenees in 409, a long period of extensive peace ended for the peninsula, and this apparently also had consequences for Empúries. The settlement withdrew to higher, easier to defend areas. The Roman planned town on the plain was abandoned, the core of the settlement was again formed by the former Palaiapolis in the area of today's Sant Martí d'Empúries. This allowed the city to continue to control the port and participate in maritime trade, which is well documented by finds of imported goods from this period, such as African sigillata or amphorae from the eastern Mediterranean.

In the 4th or 5th century, the city became a bishopric and remained so until the Visigothic period . In 616 a bishop in Tarraco signed the episcopus Impuritani Civitatis . The civitas thus existed beyond the end of the Western Roman Empire. Since the Arab invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 711, there are no more written sources about the bishopric or the city.

middle Ages

About a century later, Sant Martí d'Empúries became the center of the County of Empúries, which was created under Carolingian influence . The strategically located settlement was used as a residence by Ermengar since 812 , which was relocated to Castelló d'Empúries at an unspecified time in the 10th or 11th century . Indications of early medieval settlement activity were mainly provided by recent excavations on Plaça Major , where fixtures were found that cut through layers of late antiquity. One of the finds is a particularly characteristic pottery from this period.

The fortified place was the scene of armed conflicts several times in the Middle Ages, for example in 1285 during the Aragonese Crusade and during an incursion by Philip III. from France to Catalonia against Peter III. from Aragón . In 1467/68, already under the rule of the Crown of Aragon , during the Catalan uprising against John II of Aragon, the king's troops besieged the place and shot at it with cannons. Several cannon balls with calibers of 21 and 41 centimeters were found on the bottom of a well during excavations at Plaça Petita.

It was not until the end of the Middle Ages that Sant Martí lost its importance, the fortifications fell into disrepair or were used as a quarry. Some remains are still visible on the southern edge of Plaça Major . In modern times, the settlement focus has shifted further south to the town of L'Escala .

Research history

The ruins of Empúries were identified as the ancient Emporiae as early as the 15th century by Joan de Margarit (1421–1484), Bishop of Girona . The first description of the facility is from 1609.

The first publicly funded excavations took place in 1846-48 in the northeastern part of the Neapolis and in the Roman forum . In 1907 the architect Josep Puig i Cadafalch presented plans to uncover the ruins and in the following year dug at the southern gate of the Roman city and a little later in the Neapolis. The other excavations from 1908-1936 headed Emili Gandia i Ortega, whose excavation diaries are kept in the local museum.

During the Spanish Civil War , the excavation work came to a standstill. In 1940 Martín Almagro resumed the excavations. The city wall, the Roman forum, the grave fields and the urban housing estates were examined in particular. The progress of the excavations was regularly published in the magazine Empúries. revista de prehistòria, arqueologia i etnologia , the first edition of which appeared in 1939. It is published by the Museu d'Arqueologia de Catalunya . With the increased tourist marketing of the Ruïnes d'Empúries , summarizing reports have been published since the 1990s, and the guide booklet has been published in English, French and German translation.

investment

Palaiapolis (oldest Greek city)

The oldest part of the settlement was built with the medieval village of Sant Martí for centuries . The possibilities of archeology are therefore limited to very few excerpts. Fragments of an archaic frieze on which two sphinxes are depicted are associated with a sanctuary of the cult of Diana of Ephesus mentioned by Strabo . This includes an altar and an Ionic capital . The objects were discovered during restoration work at the beginning of the 20th century near the church, the oldest parts of which date from the 10th century.

More recent excavations below the Plaça Major uncovered parts of several residential buildings that date back to between 575 and 550 BC. BC, the oldest settlement phase of the Greek Apoikie . These were houses with a rectangular floor plan, stone plinths and tamped clay floors.

The Palaiapolis was surrounded by a mighty wall, the remains of which were exposed in 1962, 1963 and 1975. Some parts are visible north of the church. So far, however, it has not been possible to clearly distinguish between ancient walls, late ancient and medieval additions, as the complex was used and rebuilt in several epochs.

Neapolis (Greek-Iberian New Town)

While the name of the Palaiapolis is occupied by Strabo, the counterpart, the Neapolis, is probably a modern word creation that goes back to Josep Puig i Cadafalch. Whether the name was used in antiquity is not certain by sources. Most of the visible remains belong to more monumental structures from the last two centuries before Christ.

The city wall, built from strikingly large blocks, took up an area of 250 × 145 meters (3.6 hectares). It was reinforced with square towers and was mostly from the 5th or 6th century BC. In the 4th century it was rebuilt and an outwork ( proteichisma ) was created. In the second quarter of the 2nd century, the southern part was moved forward 25 meters to the south to make room for temples and the associated porticos . You enter the city on the circular path through the gate in its younger part, the earliest finds from the second half of the 6th century are more from the northern city districts.

Behind the southern gate, an alley led into the city, which separated two holy districts. The temple attributed to Serapis was located on the square to the east . The importance of the sanctuary to the west of the alley is revealed by the location of the temple and plaza on a raised terrace. As a result, this temple complex shows clear echoes of Hellenistic monumental architecture. The square has been redesigned several times and has a complicated history. At times there was a monumental altar and two temples. Towards the end of the 1st century BC A third temple was built over the abandoned city wall.

The 52 × 40 meter agora also has a monumental character . Several residential buildings near the port were demolished for their construction. Its northern side was delimited by a 52-meter-long, two-story portico . On the other three sides were single-storey porticoed halls.

The remains of the residential development visible today come from the last settlement phase. With atrium , impluvium , and in some cases peristyle , the building type largely followed Italian models of that time. Remains of the furnishings are often ornamentally decorated opus signinum floors. In one room of a building in the port area, the Greek inscription ΗΔΥΚΟΙΤΟΣ has been preserved on one of these . It can be translated as “cozy camp”.

Asclepius Temple

Within the higher, southwestern temple area, a larger temple building in the far north is known as the Asklepios Temple . In 1909 a high quality statue of the god of healing was found during excavations, which is now in the Museu d'Arqueologia de Catalunya in Barcelona. A copy is made on site. Whether the consecration referred only to the temple or the entire sacred area with several temple complexes, porticos and a free-standing altar must remain open.

The discovery of another statue head in the same year was for a long time attributed to the goddess Aphrodite , more rarely to Artemis . However, a fracture surface at the highest point of the skull proves that it is a youthful representation of Apollon Lykeios , revered in Athens , who is shown in the usual posture with his right arm above his head. The erection of a statue of Apollo, father of Asclepius, would have made perfect sense in the sanctuary.

Only a few statements can be made about the equipment of the temple complex. Several pieces of architecture found in this area in 1989 show floral decorations that are dated to the 5th century. The building should therefore belong to this time, as it also covered part of the earliest city wall. In the immediate vicinity was another temple with a double altar, the function of which cannot yet be explained.

Serapis sanctuary

In addition to the southwestern cult area, also known as the Acropolis, was the southern urban expansion of the 2nd century BC. Another larger temple complex east of the city gate. The discovery of a bilingual inscription has secured it as a temple of Serapis . The consecration of the temple and portico mentioned there by a native Alexandrian is particularly revealing . The inscription thus proves the spread of the cult, which was widespread in the Hellenistic period, to the western Mediterranean.

The temple itself was located in a 25 x 46 meter area framed by porticoes. From an older temple building from the third quarter of the 2nd century BC. Some column foundations of the portico have been preserved, finds of Doric capitals and column shafts are also attributed to a previous building.

The visible remains date from the second quarter of the 1st century BC. It was a prostyle temple with a rectangular cella , which was executed in Opus Certum construction. It is still there almost up to the original height of the podium (1.80 meters). The floor plan of the podium, a so-called cyma reversa , has models in Italian. The stairways on the long sides are striking. The construction was repeated on the forum temple of the Roman planned city. During the imperial period, it was found more frequently at temples of the imperial cult , on the Iberian Peninsula, for example, at the so-called Diana Temple in Emerita Augusta or at the Temple of Évora .

Port facility

A larger port district stretched northeast of the Neapolis. A well-preserved wall structure on the beach is traditionally referred to as a Greek pier . It is still 79.4 m long, 5.3 m wide and 4.8 m high. The breakwater lies mostly on a rock in front of the coast and consists of carefully hewn blocks with an opus caementitium core.

The function and dating of the monument are not as clear as the name. If it is used as a landing stage for ships, the question arises whether the water level was significantly higher in antiquity. It is more likely to act as a breakwater for the port against more frequent storms from the east. The dating of the complex can only be done with caution due to the few finds. Inclusions of ceramics in the cast cement date from the Roman Republican period, but not from the later imperial period. The construction technology also shows that it could have been built in the time of the Roman Republic at the earliest. In addition to the area of the former estuary and the area protected by the pier, other smaller bays have probably also been used as harbors.

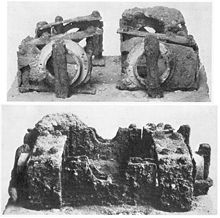

The gun find from Ampurias

In 1912, near the south gate of the New Town, Emili Gandia i Ortega discovered a depot with metal objects that were probably made in the first half of the 1st century BC. Were deposited there. Initially, the finds were thought to be car parts, but it was not until 1914 that Walter Bartel correctly interpreted the pieces as a tenter frame ( capitulum ), and thus as the central component of a ballista . The construction and the dimensions corresponded very precisely to the information in ancient texts on the construction of these torsion guns in the Hellenistic period.

With the help of Erwin Schramm , who had already recreated guns based on descriptions by ancient authors, a replica of the so-called Ampurias gun was made. This is considered to be one of the best replicas of ancient guns because it refers to both written sources and the archaeological find. The Ampurias gun gave good results in attempts to fire. The replica is shown together with Schramm's other guns in the Saalburg Museum.

Roman Municipium

Towards the end of the 2nd century BC A Roman city was built about a hundred meters west of the Neapolis. The Neapolis was only abandoned in Flavian times , so that both cities existed in parallel for at least 150 years. The city has the shape of an elongated rectangle with an area of 300 × 700 meters or 21 hectares. A little over four hectares of this have been archaeologically excavated and preserved. A right-angled road network divided the city into 35 × 70 meter insulae . The size was already given by the early Roman military station ( praesidium ), parts of which could be exposed between the later residential buildings. This is mainly a cistern complex north of the visible Roman houses. The function of a transversal wall, which separated the Pomerium into a smaller north and a larger south part, is not entirely clear . It is possible that Livy and Strabo were referring to the conditions during the authors' lifetime when mentioning such a wall in the Greco-Iberian city, which would explain why such a wall was only found in the later Roman city.

In the eastern part of the city, the foundations of three larger buildings have been exposed. These were spacious houses of the Italian type from the 1st century AD. The houses were already superimposed on the city wall, which had become inoperable. The front part was built around an atrium . The rear, eastern part of two houses formed a large peristyle , where gardens and larger water basins were. The walls of the buildings were made of clay on a stone plinth, on which wall paintings were applied. The floors were made of mosaics or opus signinum .

Forum

In the middle of the southern part of the city, on the main street ( Cardo Maximus ), are the excavated remains of the forum . It occupied the area of four insulae . At the northern end there was a four-column podium temple in the form of a pseudoperipteros . It may have been dedicated to Iupiter Optimus Maximus or the Capitoline Triassic . Conversions from the middle of the 1st century BC BC, as well as the addition of side stairs, are possibly connected with an honorary inscription for Marcus Iunius Silanus , which is only preserved in fragments. The design of the facility, found architectural parts and the foot size used suggest that the conversion was carried out by an Italian architect.

The temple was framed by three double-nave porticos with underlying crypto porticos . On the southern side there were smaller shops ( tabernae ) that opened onto the square.

Amphitheater and palaestra

Outside the southern section of the city wall there were other public buildings, to the west of the main street the amphitheater, to the east of it a walled, rectangular square, which is interpreted as a palaestra .

The amphitheater was built at the beginning of the first century BC. Built in BC. The construction is relatively simple. The foundation walls on which there were wooden benches have been preserved. Together with the Tarraco amphitheater , it is one of the only structures of this type discovered in Catalonia.

city wall

Larger sections of the rectangular city wall in the south are well preserved. To the east of the gateway there are even still wagon tracks to be seen. The wall consists of two parts, the substructure of large limestone blocks, the larger superstructure was made of cast cement (opus caementitium) . Towers are not proven. The erection of the wall is likely to coincide with the construction of the Roman city at the end of the 2nd century BC To be set. A phallic symbol is carved into a cuboid near the southern gate . In ancient times, the symbol stood for strength, luck or fertility, and it was sometimes ascribed an apotropaic effect.

Burial grounds

The extensive burial grounds of the ancient cities were not carefully examined for a long time. The contents of the graves were looted and ended up in the art trade without any scientific analysis. Only after the Spanish Civil War did Martin Almagro carry out scheduled investigations.

The earliest burials came from the time immediately before the Greek colony was founded on the western slope of the hill Les Corts and were located north of the Roman house 1. They were typical cremation burials of the urnfield culture . Necropolises of the Greek settlers were found south of the Neapolis in the area of today's dunes and the parking lot. The Portitxol cemetery was excavated before the regular investigations began. Only a few pieces from it have found their way into the museum's holdings. At least the necropolis was occupied in the 6th century, which identifies it as the burial place of the Palaiapolis. More recent graves of the Neapolis were in the Bonjoan necropolis under the today's parking lot. They lasted until the first century BC. BC back. In the early days there were cremations and body burials next to each other, which indicates that at that time the cultural influences in the twin city had not yet been completely mixed. Another necropolis from the pre-Roman period was found between Sant Martí d'Empúries and the Roman settlement.

The most important burial ground of the Roman period was Castellet on the hill Les Corts southwest of the city. The name comes from an upright grave monument that was erected using the Opus Caementitium method. The burials continued there in the second century BC. A. Most of them were cremations, graves in the form of round mounds ( tumuli ) indicate Italian burial customs.

The grave fields of late antiquity are not so widely spread around the city. During this period, burials again concentrated in the area around the hill of Sant Martí. The Neapolis was used as a cemetery due to its proximity to the early Christian basilica. The burials of this time were body graves without gifts.

literature

- Xavier Aquilué, P. Castanyer, M. Santos, J. Tremoleda: The greek city of Emporion and its relationship to the Roman Republican city of Empúries. In: L. Abad Casal, S. Keay, S. Ramallo Asensio: Early roman towns in Hispania Tarraconensis. Portsmouth 2006, ISBN 1-887829-62-8 ( Journal of Roman Archeology Supplementary Series 62 ), pp. 18-31.

- Pedro Barceló : Emporiae. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 3, Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01473-8 , Sp. 1018 f.

- Tanja Gouda: The Romanization Process on the Iberian Peninsula from the Perspective of the Iberian Cultures. Kovač, Hamburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8300-5678-2 , pp. 205-224 ( Antiquitates 54 ).

- Emil Huebner : Emporiae. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume V, 2, Stuttgart 1905, Col. 2527-2530.

- Ricardo Mar, Joaquín Ruiz de Arbulo: Ampurias romana. Historia, arquitectura y arqueología. Editorial Ausa, Sabadell 1993, ISBN 84-86329-85-X .

- Roger Marcet, Enric Sanmartí: Empúries. Diputació de Barcelona 1990, ISBN 84-7794-105-X

- Roger Marcet, Enric Sanmartí: Empúries. Guide and signpost. Diputació de Barcelona 1990, ISBN 84-7794-015-0 (German) = Guide itinéraire d'Empúries. Diputació de Barcelona 1992, ISBN 84-7794-017-7 (French).

- Museu d'Arquelogia de Catalunya-Empúries (ed.): Sant Martí d'Empúries. Una illa en el temps. Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Cultura 1998, ISBN 84-393-4543-7 .

- Enric Sanmartí-Grego: Recent Discoveries at the harbor of the Greek City of Emporion (L'Escala, Catalonia, Spain) and its Surrounding Area (Quarries and Iron Workshops). In: Barry W. Cunliffe (Ed.): Social complexity and the development of towns in Iberia: from the Copper Age to the second century AD. Oxford Univ. Press, 1995, ISBN 0-19-726157-4 , pp. 157-174 (Proceedings of the British Academy 86).

- Heinz Schomann: Art monuments of the Iberian Peninsula. Part III . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1998, pp. 46–48.

- Birgit Tang: Delos, Carthage, Ampurias: the housing of three Mediterranean trading centers. "L'Erma" di Bretschneider, Rome 2005, ISBN 88-8265-305-6 (Analecta Romana Instituti Danici Suppl. 36).

- Walter Trillmich and Annette Nünnerich-Asmus (eds.): Hispania Antiqua - Monuments of the Roman Age. von Zabern, Mainz 1993, ISBN 3-8053-1547-3 , esp. pp. 72–80, cat. pp. 250–254, plates 6–11. Location register p. 483.

Magazine:

- Empúries: revista de prehistòria, arqueologia i etnologia. (up to No. 42, 1982: Ampurias ) Published by the Museu d'Arqueologia de Catalunya, Barcelona (Spanish / Catalan).

Web links

- Entries on Empúries in the Arachne archaeological database

- Museu d'Arquelogia de Catalunya-Empuries

- The excavations of Empúries

- Page about the Ruïnes d'Empúries with photos

Individual evidence

- ↑ Leandre Villaronga: Les Monedes de plata d 'Empòrion, Rhode i les seves imitacions: de principi del segle IIIaC fins a l'arribada dels romans el 218aC. Societat Catalana d 'Estudis Numismàtics, Institut d'Estudis Catalans, Barcelona 2000, ISBN 84-7283-537-5 (Acta numismatica Complements 5) Plate XXIX No. 400.

- ↑ a b c d e Strabon 3.4.8 - engl. Text by LacusCurtius .

- ↑ a b R. Marcet, E. Sanmartí: Empúries. 1990 p. 16.

- ↑ On the term see Sitta von Reden : Emporion. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 3, Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01473-8 , column 1020 f.

- ^ Brian B. Shefton : Greek Imports at the Extremities of the Mediterranean, West and East: Reflections on the Case of Iberia in the Fifth Century BC In: Barry W. Cunliffe (Ed.): Social complexity and the development of towns in Iberia : from the Copper Age to the second century AD . Oxford University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-19-726157-4 , pp. 127-155 (Proceedings of the British Academy 86).

- ^ R. Marcet, E. Sanmartí: Empúries. 1990 pp. 11 and 21; M. Blech: Archaeological sources on the beginnings of Romanization. In: Hispania antiqua p. 72.

- ↑ a b c Livy XXXIV 9; Latin text at www.thelatinlibrary.com .

- ^ Emil Huebner : Emporiae. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume V, 2, Stuttgart 1905, Col. 2528.

- ^ R. Marcet, E. Sanmartí: Empúries. 1990 pp. 16 and 19f.

- ↑ a b M. Blech: Archaeological sources on the beginnings of Romanization. In: Hispania Antiqua , p. 74.

- ↑ Leandre Villaronga: Les Monedes de plata d 'Empòrion, Rhode i les seves imitacions: de principi del segle IIIaC fins a l'arribada dels romans el 218aC. Societat Catalana d 'Estudis Numismàtics, Institut d'Estudis Catalans, Barcelona 2000, ISBN 84-7283-537-5 ( Acta numismatica Complements 5 ).

- ^ Livy XXI, 60f .; Latin text at www.thelatinlibrary.com; Polybius, III, 76 .

- ^ Livy XXVI 19; Latin text at www.thelatinlibrary.com .

- ↑ Livy XXVIII, 42; Latin text at www.thelatinlibrary.com .

- ^ Livy XXXIV 8; Latin text at www.thelatinlibrary.com .

- ^ R. Marcet, E. Sanmartí: Empúries. 1990, p. 28.

- ↑ Sallust: Historiae II 98.5; Latin text at www.thelatinlibrary.com .

- ^ Enric Sanmartí-Grego: La cerámica campaniense de Emporion y Rhode. Diputación de Barcelona 1978 ( Monografías Ampuritanas 4).

- ^ R. Marcet, E. Sanmartí: Empúries. 1990, p. 32.

- ↑ For silting up see Sant Martí d'Empúries. Una illa en el temps. Pp. 14-17.

- ^ Emil Huebner : Emporiae. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume V, 2, Stuttgart 1905, Col. 2530. Pedro Barceló : Emporiae. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 3, Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01473-8 , Sp. 1018.

- ↑ CIL 02.06183 ; CIL 02, 06184b .

- ↑ See Michael Kulikowski: The Late Roman City in Spain. In: Jens Uwe Krause / Christian Witschel (eds.): The city in late antiquity - decline or change? Files from the international colloquium in Munich on May 30 and 31, 2003. Steiner, Stuttgart 2006 pp. 129–149.

- ↑ Sant Martí d'Empúries. Una illa en el temps. P. 37.

- ^ R. Marcet, E. Sanmartí: Empúries. 1990, p. 34.

- ↑ Sant Martí d'Empúries. Una illa en el temps. P. 39.

- ↑ Jeroni de Pujades: Corónica universal del Principat de Cathalunya. Barcelona 1609.

- ^ Josep Puig i Cadafalch : Les excavacions d'Empúries. Estudi de la topografia. In: Anuari de l ' Institut d'Estudis Catalans 1908. pp. 150-194.

- ↑ Enric Sanmartí (ed.): El Fòrum Romà de Empúries. Excavacions de l'any 1982. Barcelona 1984 ( Monografies Empuritanes VI ).

- ↑ a b Martín Almagro: Las Necrópolis de Ampurias. I. Introducción y Necrópolis Griegas. Seix y Barral, Barcelona 1953; II. Necrópolis Romanas y Necrópolis Indígenas. Seix y Barral, Barcelona 1955 ( Monografies Empuritanes III ).

- ↑ Up to No. 44, 1982 as Ampurias published by Diputación Provincial de Barcelona, Instituto de Prehistoria y Arqueología; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Instituto Español de Prehistoria Empúries .

- ↑ Sant Martí d'Empúries. Una illa en el temps. P. 26f; Enric Sanmartí, Josep M. Nolla: Guide itinéraire d'Empúries. 1992, pp. 62f.

- ^ Enric Sanmartí, Josep M. Nolla: Guide itinéraire d'Empúries. 1992, p. 61.

- ↑ Sant Martí d'Empúries. Una illa en el temps. P. 27f.

- ^ Enric Sanmartí, Josep M. Nolla: Guide itinéraire d'Empúries. 1992, p. 60; for the medieval and modern fortifications and their history, see Sant Martí d'Empúries. Una illa en el temps. Pp. 41-45.

- ↑ Enric Sanmartí-Grego, P. Castañyer i Masoliver, J. Tremoleda i Trilla: Emporion: un ejemplo de monumentalización precoz en la Hispania republicana (Los santuarios helenísticos de su sector meridional). In: Walter Trillmich and Paul Zanker (eds.): Cityscape and Ideology. The monumentalization of Hispanic cities between republic and imperial times. Colloquium Madrid from October 19 to 23, 1987. Munich 1990 pp. 117–144 (Bavarian Academy of Sciences, Philosophical-Historical Class, treatises NF 103).

- ↑ For example in the guide booklet Enric Sanmartí, Josep M. Nolla: Guide itinéraire d'Empúries. 1992, p. 24.

- ↑ SF Schröder in: Hispania antiqua p. 253 f.

- ^ R. Marcet, E. Sanmartí: Empúries. 1990 p. 83 f.

- ↑ CIL 02.06185 ; HEp 4, 1994, 372 .

- ^ Theodor Hauschild in: Hispania antiqua p. 252.

- ↑ Information from E. Sanmartí-Grego: Recent Discoveries at the harbor of the Greek City of Emporion (L'Escala, Catalonia, Spain) and its Surrounding Area (Quarries and Iron Workshops). In: Barry W. Cunliffe (Ed.): Social complexity and the development of towns in Iberia: from the Copper Age to the second century AD. Oxford Univ. Press, 1995, p. 166.

- ^ E. Sanmartí-Grego: Recent Discoveries at the harbor of the Greek City of Emporion (L'Escala, Catalonia, Spain) and its Surrounding Area (Quarries and Iron Workshops). In: Barry W. Cunliffe (Ed.): Social complexity and the development of towns in Iberia: from the Copper Age to the second century AD. Oxford Univ. Press, 1995, pp. 170 f.

- ^ R. Marcet, E. Sanmartí: Empúries. 1990 p. 116.

- ↑ For the Ampurias gun see Dietwulf Baatz : Recent Finds of Ancient Artillery. In: Britannia, 9: 1-17 (1978); Erwin Schramm: The ancient artillery of the Saalburg. Reprint of the 1918 edition with an introduction by D. Baatz. Supplement to the Saalburg yearbook, Saalburg Museum, Bad Homburg vdH 1980 pp. 40–46.

- ^ R. Marcet, E. Sanmartí: Empúries . 1990 p. 28f.

- ^ R. Marcet, E. Sanmartí: Empúries . 1990 p. 63.

- ↑ HEp-01, 00341 .

- ↑ M. Blech: Archaeological sources to the beginnings of the Romanization. In: Hispania antiqua p. 78.

- ↑ For the two structures see M. Almagro: El Anfiteatro y la palestra de Ampurias. Ampurias, 17, 1955-56.

- ^ R. Marcet, E. Sanmartí: Empúries . 1990 p. 168 f.

- ↑ Sant Martí d'Empúries. Una illa en el temps. P. 38; R. Marcet, E. Sanmartí: Empúries . 1990 p. 171.

Coordinates: 42 ° 8 ′ 5.9 ″ N , 3 ° 7 ′ 10.6 ″ E