Aljamiado

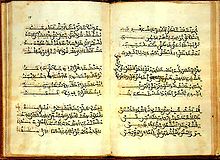

Extract from manuscript "B", BNE , Codex Res. 247, olim Gg. 101.

An aljamiado text dated between the 14th and 16th centuries.

In the narrower sense, “Aljamiado literature” in Hispanic studies means texts from the Mudejares , that is, the Muslims who came under the rule of the Christian kingdoms in Spain during the Reconquista , and texts from the Moriscos , that is , those who were forcibly converted to Christianity Moors who lived in Spain from 1502 to circa 1610 after the completion of the Reconquista. Your literary products are Spanish in terms of language and content, but Arabic in terms of writing, i.e. foreign to Romansh Spaniards. And vice versa: according to the script, they are Arabic, but foreign to Arabs in terms of language and content.

In analogy to the Islamic Aljamiado literature, the Hispanic Arabic term Aljamiado is also used in Romance studies for Romance texts written in the Hebrew alphabet . For the Jews living in al-Andalus used the Hebrew alphabet not only when they wrote texts in the Hebrew language, but also when they wrote down Judeo- Spanish , Judeo-Catalan , Judeo-Portuguese or Judeo-Arabic texts.

In the broadest sense, philologists - quite generally - speak of "Aljamiado notation" when a linguistic message is presented in a writing system that is foreign to this language.

The Al-Andalusian Aljamiado literature is of extraordinary importance for Romance studies , because the oldest complete texts in Ibero-Roman language forms have survived in this alienated spelling, i.e. in Arabic and Hebrew : the Mozarabic Chardjas (Spanish jarchas ). These old Spanish chardjas, closing verses of Arabic and Hebrew muwashschahas , provide the earliest evidence of poetry in the Romance language.

Semantics and etymology

"Aljamiado" is a Spanish adjective:

"Aljamiado, -a, adj. Se aplica al texto romance escrito en caracteres arábigos. "

"The adjective 'aljamiado, -a' describes a Romance text that is written in Arabic characters."

The Arabic etymon " adschamiya /عجمية / ʿAǧamīya ”of the Spanish adjective “ aljamiado ”means foreign language in the sense of“ non-Arabic language ”. Texts in Aljamiado spelling (Spanish "textos en escritura aljamiada") are linguistic monuments that are written in Arabic script - but not in Arabic.

"Aljamía" is a Spanish noun:

"Aljamía (del ár. And. Al'agamíyya) 1 f. Para los musulmanes que vivían en España: lengua romance y, en general, lengua extranjera. 2 Escrito en lengua romance con caracteres arábigos. "

“(Derived from Andulsian-Arabic 'al'agamíyya' ['non-Arabic']). 1 f. The Muslims who lived in Spain used 'aljamía' to refer to the Romance language and, in general, to any foreign language. 2 Document in Romance language, which is written in Arabic letters [ie: 'Aljamiado text'] "

The technical terms "Aljamiado" and "Aljamía" are used synonymously. One speaks equally of Aljamiado literature and Aljamía literature.

Aljamiado texts as the subject of interdisciplinary research

In the Middle Ages, three cultures, each with a monotheistic religion and each with their own alphabet, coexisted on the Iberian Peninsula : Romanic Christians, Arab-Berber Muslims ( Moors ) and Jews. For more than eight centuries - from the Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula (from 711 Tariq ) to the flight and expulsion of Muslims, Sephardic Jews (from 1492 Alhambra Edict ) and Moriscus (from 1609 Philip III ) - the Moorish al -Ándalus three different writing systems in use depending on the culture: the Latin, the Arabic and the Hebrew alphabet. As a rule, the Islamic Moors also used the Arabic characters when writing in one of the Romance vernacular languages . Likewise, the Jews used the Hebrew alphabet not only when they wrote texts in the Hebrew language, but also when they wrote down Judeo- Spanish , Judeo-Catalan , Judeo-Portuguese or Judeo-Arabic texts. Therefore, in Romance studies, the term Aljamiado, which comes from Hispanic Arabic, is used in analogy to the Moorish Aljamiado literature also to those Romance texts that are written in Hebrew letters.

A particular problem arises with the deciphering of aljamiado texts , i. H. when re- transcribing into the Latin alphabet. In the Aljamiado notation the vocalization , the representation of the vowels, is missing ; because both the Arabic and the Hebrew writing systems are consonant scripts . In consonant writings can vowels through diacritical characters dotted represent, but in older texts such vowels are missing mostly complete, so that the Romanesque-Latin vowels in reading guess and put itself must. This is why studying the Aljamiado manuscripts requires interdisciplinary collaboration between Arabists , Hebraists and Romanists . Expertise in Arabic and Hebrew palaeography is essential for the critical and exact editing of the manuscripts .

Aljamiado Verses: Romance Chardjas in Arabic and Hebrew Muwashschahs

The oldest Aljamiado texts, Romanesque Chardjas in Hebrew and Arabic Muwashschahas, which reproduce poetry in ancient Spanish from the 11th century in Hebrew and Arabic characters, were only rediscovered very late. In 1948 Romance philology experienced this great moment. The young Hebrew scholar Samuel Miklos Stern discovered, deciphered and published in an article in French twenty in Hebrew Aljamiado notation authored old Spanish ( Mozarabic ) Chardschas to which he in studying Hebrew Muwaschschah -Handschriften had noticed. The Romanist and Almajiado researcher Reinhold Kontzi describes this in an essay as follows:

“ The fame of this literary genre [Muwaššaḥ] penetrated as far as the Arab East. There the muwassahas from Al-Andalus were written off by Muslims and Jews. They eventually ended up in libraries, archives and synagogues. In this there is a place - the Genisa - where old documents, waste equipment and any kind of unnecessary writings 'buried' were, because they were considered too sacred to be destroyed. Some of these rooms were walled up over time. When the Cairo Genisa was uncovered in 1763, around 100,000 manuscripts were found. Among this material, Samuel Miklos Stern, a young Israeli scholar, found twenty Hebrew muwassahas with Romance hargas, which he published in 1948 in Al-Andalus, the journal of the Spanish Arabists [in French]. "

Samuel M. Stern was interested in the Arabic stanza poem genre, the Muwaššaḥ, invented in al-Andalus . In the foreword to the Muwaschschah anthology by the medieval Egyptian poet Ibn Sana al-Mulk (1155–1211), Dar at-tiraz , he found a poetics of Muwaschschah. Ibn Sana al-Mulk puts forward the theory that the genus of Muwashschah was invented in the Moorish al-Ándalus. In addition, the stanza form was taken over from popular Romance songs. In order to give their poems a fiery local color , the Arab poets from al-Ándalus wrote the closing verses of the last stanza, the Harga , in Andalusian-Arabic and even in Romance dialect (Aljamiado spelling) , probably inspired by the folk songs of Mozarabic Christian women .

When, while reading medieval Hebrew muwaššaḥs, SM Stern came across enigmatic hargas whose consonant order made no sense in Hebrew, he remembered Ibn Sana al-Mulk's anthology Dar at-tiraz , which spoke of Chardjas in non-Arabic was, and it occurred to him that it could be such old Spanish Jarchas.

The example of Harga No. 16, published by him, can be used to follow the decipherment. The transliteration from the Hebrew consonant writing into the Latin alphabet results in an incomprehensible, puzzling consonant sequence. It is neither a Hebrew nor an Arabic dialect, in which the Chardashes known up to then are composed:

- ky fr'yw 'w ky šyr'd dmyby

- hbyby

- nwn tytwlgš dmyby

Samuel M. Stern tried to vocalize the consonant sequence and old Spanish words came up. In memory of Ibn Sana al-Mulk's thesis of Romance songs in oriental Jarchas, he continued the transcription and succeeded in reconstructing the old Spanish texts:

- Qué faré yo o qué serad de mibi

- habibi

- non te tolgas de mibi.

Translated into today's Spanish:

- ¿Qué haré yo o qué será de mí?

- Mi amado,

- ¡No te apartes de mí!

in German:

- What will I do or what will I become?

- Beloved,

- don't leave me!

The discovery of Romanic Aljamiado poetry in Hebrew Muwashschah manuscripts was soon followed by finds of Romanesque hargas in Arabic Muwashschah manuscripts. In 1952, for example, the Spanish Arabist Emilio García Gómez published 24 Romance Chardjas, which he had discovered in Arabic muwashshahas , inspired by SM Stern's publications .

In 1988 Alan Jones published a text-critical and palaeographically exact edition of over 42 Romanesque hargas previously discovered in Arabic muwashschahas. Forty years after their discovery, these Aljamiado texts were made available to the public for the first time - through facsimiles of the original manuscripts in Arabic script. Possible readings , conjectures and emendations of each Harga are discussed letter by letter .

The motifs of these Romanesque hargas are reminiscent of the popular old Galician-Portuguese cantigas de amigo , in which girls in love sing about the longing for their lover. Until the discovery of these Ibero-Roman jarchas from al-Ándalus in the 11th century, the old Occitan courtly, refined trobadord poetry of southern France (12th century) was considered the oldest evidence of poetry in the Romance language.

In terms of literary history, the question of the origin of the old Occitan trobadord poetry and Romance poetry in general arises again.

These Aljamiado texts are not only of great importance for Romanists in terms of literary history, but also in terms of linguistic history. The Mozarabic Hargas are the oldest completely surviving texts of Iberro-Roman language forms and thus provide the most important text corpus of the historical Mozarabic by al-Ándalus.

Aljamiado manuscripts of the Mudejares and the Moriscos

If the text corpus of secured Mozarabic Aljamiado verses, the Hargas, relatively thin, the rich, the corpus is Aljamiadoliteratur from a later period, from the beginning of the Reconquista . The Muslims in the areas that were gradually recaptured by Spanish Christians, especially in Aragón , were allowed to practice their Islamic religion under certain conditions and were called Mudéjares , the tolerated ones . They continued to use the Arabic sign system even when writing Romance texts. The most important surviving Aljamiado script from the Mudéjar era is the Poema de Yúçuf (14th century) in the old Aragonese dialect (see the facsimile commented above on the right). After the end of the Reconquista (1492), Muslims were only allowed to stay in Spain if they converted to Christianity. Mudéjares that were tolerated became forcibly converted moriscos . Bans on speaking Arabic in public soon followed (in Granada in 1526, in Aragón in 1566). The Morisks kept the Arabic alphabet, even if they no longer wrote texts in Arabic. The corpus of Aljamiado literature from the Moriskian era is the most extensive. Most of the finds come from Aragón, where they were mostly accidentally made when old houses were demolished. So one found z. B. 1884 in Almonacid de la Sierra the remains of the magazine of a Moriski bookseller with numerous Aljamiado manuscripts, including crypto literature , d. H. Underground literature kept secret, translations of officially forbidden Islamic-religious texts. The Aljamiado manuscripts of the Mancebo de Arévalo , a morisk who came to Aragón around 1502, are well preserved. He is the author of spiritual-Islamic works such as Breve compendio de santa ley y suna , Tafçira , Sumario de la relación y ejercício espiritual and a calendario musulmán , an Islamic moon calendar, recently rediscovered by Luis F. Bernabé de Pons .

The majority of the Moriskan Aljamiado texts are translation literature. The Romanist and Arabist Álvaro Galmés de Fuentes organized an international colloquium in 1972 in Oviedo on Moriskan Aljamiado literature. In the publication of the materials he classified the Moriskan Aljamiado script as follows:

- Islamic-religious crypto literature (official forbidden texts, anti-Christian and anti-Jewish writings)

- El Evangelio de Bernabé

- Los siete alhaicales. Plegarias moriscas (Moriskan intercession)

- Biblical legends from a Koranic perspective

- Poema de José also called L'Alhadiç de Yúçuf .

- L'Alhadiç de Ibrahim (Historia del sacrificio de Ismael)

- Narrative prose (La leyenda de la doncella Carcayona; Recontamiento del rey Alisandra; Libro de las batallas)

- Eschatological texts (Estoria del día del juicio; Ascención de Mahoma al los cielos)

- Ascetic and mystical literature (works by Mancebo de Arévalo, already quoted above)

- Treatises on popular beliefs and superstitions (Libro de dichos maravillosos)

- Didactic prose (Los castigos de 'Ali)

- Lyric texts (Almadha de alabança al annabí Mahomad)

- Travel literature (Itinerario de España a Turquía)

- Legal texts (Leyes de moros)

Example of an aljamiado poem with Islamic content: "Poema de José"

Aljamiado texts by Jewish scribes

Like Yiddish , Jewish-Spanish is usually written in the Hebrew alphabet. The Sephardim continue this Judenspanish Aljamiado tradition to this day.

Aljamiado literature outside of Romania

There are Aljamiado texts written in the Arabic alphabet outside of Romania, such as B. in Serbo-Croatian, Albanian (Kalesi 1966/67), Greek (Theodorisis 1974), Belarusian, Latin (Hegyi 1979), Hungarian and German. Aljamiado literature can also be found outside Europe, e.g. B. in Africa and Asia:

- “A highly interesting case of these phenomena is the Cape Malay literature, Afrikaans in Arabic script, researched by Kähler (1971). Many analogous cases of this type can also be found in Africa and Asia, including Chinese texts in Arabic script (Bausani 1968 , Forke 1907). The common feature of these literatures is that they are languages for which Arabic is not the standard alphabet. In addition to the use of the Arabic alphabet, such scripts also differ in other features from the respective standard languages. Borrowings from Arabic play a major role here. "

See also

- Ajami script (uses of the Arabic script for languages other than Arabic)

- List of Arabic-based alphabets

- Maltese language (Maltese is the only Semitic language that uses Latin letters)

- Persian alphabet (Persian, an Indo-European language , has been written using a modified form of the Arabic alphabet since medieval Islamization).

- Urdu (Indo-European Urdu is the official language in Pakistan and in some Indian states). Urdu uses a variant of the Persian alphabet, which in turn is a variant of the Arabic alphabet.

- Xiao'erjing (the practice of writing Sinitic languages such as Chinese (especially the Lanyin dialect , Zhongyuan dialect and Northeastern dialect ) or the Dungan language in Arabic script )

literature

- Colección de Literatura Española Aljamiado-Morisca (CLEAM) Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Oviedo: Volumes published so far - Server of the Seminario de Estudios Árabo-Románicos (SEAR) of the University of Oviedo .

Bibliographies

- Digital Bibliography of Aljamiado Literature - Oviedo University

- Luis F. Bernabé Pons: Bibliografía de la literatura aljamiado-morisca . Universidad de Alicante 1992, ISBN 84-7908-071-X .

- Álvaro Galmés de Fuentes: Los manuscritos aljamiado-mosriscos de la Biblioteca de la Real Academia de la Historia . Legado Pascual de Gayangos. Madrid 1998, ISBN 84-89512-07-8 : Google books .

- Alois Richard Nykl : Aljamiado literature. El Rrekontamiento del Rrey Alisandere . History and classification of the Aljamiado literature . In: Revue Hispanique. vol. 77, n ° 172, 1929, pp. 409-611, New York 1929, ISSN 9965-0355 .

- Eduardo Saavedra: Discursos Leídos ante La Real Academia Española En La Recepción publica Del 29 De Diciembre 1878. Apéndice I - Índice General de la Literatura Aljamiada. P. 162. ( online p. 299. )

- Juan Carlos Villaverde Amieva: Los manuscritos aljamiado-moriscos: hallazgos, colecciones, inventarios y otras noticias . Universidad de Oviedo. (pdf)

On the subject of " Chardschas "

- Emilio García Gómez: Las jarchas de la serie arabe en su marco. Edición en caracteres latinos, version española en calco rítmico y estudio de 43 moaxajas andaluzas. Sociedad de Estudios y Publicaciones, Madrid 1965.

- Alan Jones: Romance Kharjas in Andalusian Arabic Muwaššaḥ Poetry. A Palaeographical Analysis (= Oxford Oriental Institute Monographs. Volume 9). Ithaca Press, London 1988, ISBN 0-86372-085-4 .

- Reinhold Kontzi: Two Romance songs from Islamic Spain. (Two Mozarabic Harǧas). In: Francisco J. Oroz Arizcuren (Ed.): Romania cantat. Dedicated to Gerhard Rohlfs on the occasion of his 85th birthday. Volume 2: Interpretations. Narr, Tübingen 1980, ISBN 3-87808-509-5 , pp. 305-318 in the Google book search.

- Samuel Miklos Stern: Les vers finaux en espagnol dans les muwassahs hispano-hébraïques. A contribution à l'histoire du muwassah et à l'étude du vieux dialecte espagnol “mozarabe”. In: Al-Andalus. Revista de las escuelas de estudios arabes de Madrid y Granada. Volume 12, 1948, ISSN 0304-4335 , pp. 299-346.

Moriskan Aljamiado literature

- Luis F. Bernabé Pons: El Evangelio de San Bernabé. Un evangelio islámico español. Dissertation. Universidad de Alicante , 1995, ISBN 84-7908-223-2 .

- Luis F. Bernabé Pons: El texto morisco del Evangelio de San Bernabé. Universidad de Granada 1998, ISBN 84-338-2418-X .

- Xavier Casassas Canals: La literatura aljamiado-morisca en el marco de la literatura islámica española. In: Los moriscos y su legado. Desde ésta y otras laderas. Instituto de Estudios Hispano-Lusos, Rabat 2010, ISBN 978-9954-30-158-6 , pp. 368-396. ( online ; PDF; 272 kB)

- Xavier Casassas Canals: Los siete alhaicales y otras plegarias aljamiadas de mudéjares y moriscos. Colección Al Ándalus. Editorial Almuzara, Córdoba 2007, ISBN 978-84-96710-83-2 .

- Ottmar Hegyi: Language in the border area between Islam and Christianity: The Aljamiado literature. In: Jens Lüdtke (Ed.): Romania Arabica. Festschrift for Reinhold Kontzi on his 70th birthday. Narr, Tübingen 1996, ISBN 3-8233-5173-7 , pp. 325–334 in the Google book search.

- Ursula Klenk: La Leyenda de Jūsuf. An aljamiado text. Edition and glossary. (= Supplements to the magazine for Romance philology. 134). Max Niemeyer Verlag Tübingen 1972, ISBN 3-484-52039-6 . Extracts . (A prose text - the basis of the edition is the manuscript BNE MSS / 5292).

- Reinhold Kontzi : Aljamiado texts 2 volumes. Volume 1: Edition with an introduction and glossary. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1974, ISBN 3-515-01781-X ; Volume 2: Texts. 1974, ISBN 3-515-01781-8 .

Aljamiado texts outside of Romania

- Reinhold Kontzi: Comparison between Aljamía and Maltese. In: Adolfo Murguía (Ed.): Language and World. Ceremony for Eugenio Coseriu on his 80th birthday. Narr, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-8233-5882-0 , pp. 125-140 in the Google book search.

- Werner Lehfeldt : The Serbo-Croatian Aljamiado literature of the Bosnian-Hercegovinian Muslims. Transcription problems . Trofenik, Munich 1969. OCLC 479786800

- Maksida Pjanić: The Arabisms in the Aljamiado Literature of Bosnia. Vienna 2009 (Vienna, university, thesis, 2010), full text pdf on: othes.univie.ac.at

Web links

- Memoria de los moriscos. Escritos y relatos de una diáspora cultura - Video published by the Spanish National Library: on YouTube

- Exhibition by the Spanish National Library: Memoria de los Mosriscos

- About transliteration problems of Jewish-Spanish Aljamiado texts of the Sephardi : Cómo transcribir textos aljamiados sefardíes

- Koran, Sura 12. Yusuf

- www.jarchas.net -55 old Spanish Chardschas . Different transliterations and transcriptions of the same Chardscha according to the reading of the respective philologist (from the diploma thesis by: Alma Wood Rivera: Las jarchas mozárabes: Una compilación de lecturas , Monterrey (México) 1969).

Footnotes

- ↑ Karima Bouras: La literatura aljamiada, aproximación general. (on-line)

- ^ Samuel Miklos Stern: Les vers finaux en espagnol dans les muwassahs hispano-hébraïques. A contribution à l'histoire du muwassah et à l'étude du vieux dialecte espagnol “mozarabe”. In: Al-Andalus Revista de las escuelas de estudios árabes de Madrid y Granada. Volume 12, 1948, pp. 299-346.

- ^ Emilio García Gómez: Estudio del "Dar at-tiraz". Preceptiva egipcia de la muwassaha. In: Al-Andalus. Revista de las escuelas de estudios arabes de Madrid y Granada. Volume 27, No. 1, 1962, pp. 21-104.

- ↑ Chardash n ° 16 written in the Hebrew alphabet

- ↑ a b Transliteration and transcription according to: Samuel Miklos Stern: Les vers finaux en espagnol dans les muwassahs hispano-hébraïques. A contribution à l'histoire du muwassah et à l'étude du vieux dialecte espagnol “mozarabe”. In: Al-Andalus. Revista de las escuelas de estudios arabes de Madrid y Granada. Volume 12, 1948, p. 329.

- ^ Samuel Miklos Stern: Un muwassah arabe avec terminaison espagnole. In: Al-Andalus. Revista de las escuelas de estudios arabes de Madrid y Granada. Volume 14, 1949, pp. 214-218. And above all: Emilio García Gómez: Veinticuatro jaryas romances en muwassahas árabes (Ms. GS Colin). In: Al-Andalus. Revista de las escuelas de estudios arabes de Madrid y Granada. Volume 17, 1952, pp. 57-127.

- ↑ Alan Jones: Romance Kharjas in Andalusian Arabic muwaššah Poetry. 1988.

- ↑ Pierre Le Gentil : The strophe “zadjalesque”, “les khardjas” and the problem of origines du lyrisme roman. In: Romania. Volume 84 = No. 334, 1963, ISSN 0035-8029 , pp. 1-27 and pp. 209-250.

- ^ Josep M. Solà-Solé: Corpus de poesía mozárabe. Las harga-s andalusíes. Ediciones Hispam, Barcelona 1973, ISBN 84-85044-05-3 .

- ↑ Ramón Menéndez Pidal : Poema de Yúçuf. Materiales para su estudio (= Colección Filológica de la Universidad de Granada. Volume 1, ISSN 0436-2888 ). Universidad de Granada, Granada 1952. Antonio Pérez Lasheras: La literatura del reino de Aragón hasta el siglo XVI (= Biblioteca Aragonesa de Cultura. No. 15 = Publicación de la Institución "Fernando el Católico". No. 2341). Zaragoza 2003, ISBN 84-8324-149-8 , p. 143.

- ↑ For example, Islamic supplications from the 15th – 17th centuries. Century, see: Xavier Casassas Canals: Los siete alhaicales y otras plegarias aljamiadas de mudéjares y mosriscos. 2007.

- ↑ Luis F. Bernabé Pons: El calendario musulmán del Mancebo de Arévalo. In: Sharq al-Andalus. Volume 16/17, 1999/2002, ISSN 0213-3482 , pp. 239-261. (Full text as PDF; 134 KB)

- ↑ On the subject of Moriskan translation literature in Ajamiado notation, see also: Raquel Montero: Las traducciones moriscas y el español islámico: Los manuscritos Toledo 235 y RAH 11/9397 (olim S 5). In: Fernando Sánchez Miret (ed.): Actas del XXIII Congreso de Língüística y Filología Románica. Salamanca 24-30 de September 2001. Volume 4: Sección 5: Edición y crítica textual. Max Niemeyer, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-484-50398-X , pp 215-222, and Raquel Montero: Alcoran. Traducción castellana de un morisco anónimo del año 1606. Introducción de Joan Vernet Ginés. Transcripción de Lluís Roqué Figuls, Barcelona ( Reial Acadèmia de Bones Lletres - Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia), 2001. In: Aljamía. Volume 15, 2003, ISSN 1135-7290 , pp. 282-287.

- ↑ Álvaro Galmés de Fuentes: Actas del Coloquio Internacional sobre Literatura Aljamiada y Morisca (= Colección de Literatura Espaõla Aljamiado-Morica. Volume 3). Gredos, Madrid 1978, ISBN 84-249-3512-8 .

- ↑ Description - in the Biblioteca virtual Miguel de Cervantes

- ↑ Xavier Casassas Canals: Los siete alhaicales y otras plegarias moriscas. Colección Al Ándalus. Editorial Almuzara, Córdoba 2007, ISBN 978-84-96710-83-2 . (Full text)

- ^ Steven M. Lowenstein: German in Hebrew letters. A comment. In: Ashkenaz, journal for the history and culture of the Jews. Volume 18-19, Issue 2, pp. 367-375, ISSN (Online) 1865-9438, ISSN (Print) 1016-4987, December 1, 2010. doi: 10.1515 / asch.2009.023

- ↑ Maksida Pjanić: The Arabisms in Aljamiado literature Bosnia. 2009, and Werner Lehfeldt: The Serbo-Croatian Aljamiado Literature of the Bosnian-Hercegovinian Muslims. Transcription problems. Munich 1969.

- ↑ See the Luther hymn 'Our Father in the Kingdom of Heaven' in the picture opposite. [Martin Luther]: Alaman Turkīsi. In: [Anon.]: Meǧmūʿa. [oOuJ] fol. 40r.-41v. http://data.onb.ac.at/rec/AL00642162 as well as digital copies of the entire work http://data.onb.ac.at/dtl/3373545 (accessed December 7, 2017, 6:00 p.m.).

- ↑ Ottmar Hegyi: Language in the border area between Islam and Christianity: The Aljamiado literature. In: Jens Lüdtke (Ed.): Romania Arabica. Festschrift for Reinhold Kontzi on his 70th birthday. 1996, here p. 325 in the Google book search.