Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| C82 | Follicular (nodular) non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

| C83 | Not follicular lymphoma |

| C84 | Mature-cell T / NK-cell lymphomas |

| C85 | Other and unspecified types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

| C86 | Other specified T / NK cell lymphomas |

| C88 | Malignant immunoproliferative diseases |

| C90 | Plasmacytoma and malignant plasma cell neoplasms |

| C91 | Lymphatic leukemia (excluding C91.0 Acute lymphatic leukemia [ALL]) |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

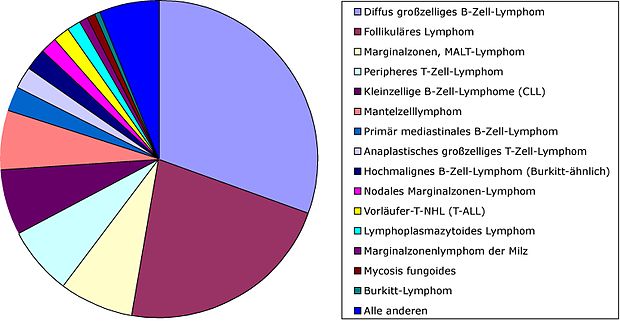

All malignant diseases of the lymphatic system ( malignant lymphomas ) that are not Hodgkin's disease are summarized under the collective term non-Hodgkin lymphoma ( NHL ) . This summary is essentially for historical reasons. The diseases that are grouped under this heading are very different. This applies to the underlying genetic changes, the immunological characteristics as well as the clinical manifestations. Accordingly, the treatment of NHL looks very different. The NHL are divided into a B line (about 80 percent of all NHL) and a T line (20 percent), depending on whether the NHL originates from B-lymphoid or T-lymphoid cells. There is also rarely NHL that originates from so-called NK cells .

causes

Basically, it can be said that NHL is always based on the uninhibited division of lymphocytes with a simultaneous lack of apoptosis of the surplus cells. The result is that the mass and number of the corresponding lymphocytes increases more and more and thus other cells are displaced.

The pathogenesis of non-Hodgkin lymphomas is not yet fully understood. As a congenital genetic defect, the NHL occurs primarily in Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome . In the majority of cases, however, acquired genetic changes are decisive for the development of lymphoma; in these cases, NHL cannot be inherited. However, there are some risk factors that complement a genetic predisposition and thus promote the development of lymphoma. These include, for example, radiation exposure through ionizing X-rays or gamma radiation or previous cytostatic therapy (for example as part of the treatment of another malignant disease). An autoimmune disease (such as Sjogren's syndrome ) or infection with HIV can also promote the development of NHL.

There are also viruses and bacteria that promote the development of NHL.

Genetic changes

In the meantime, a large number of genetic changes have been identified, some of which are of diagnostic importance when it comes to the precise classification of NHL. Certain chromosome translocations are typical :

- t (8; 14) (q24; q32) - typically in Burkitt's lymphoma , diffuse large-cell B-NHL , rarely multiple myeloma

- t (11; 14) (q13; q32) - typical of mantle cell lymphoma , occasionally multiple myeloma or chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- t (14; 18) (q32; q21) - typical of follicular lymphoma

These chromosome translocations cause certain oncogenes to run out of control, which is a crucial step in the malignant transformation of the affected cell.

Oncogenic Viruses and Bacteria

In some NHL subtypes, certain viruses and bacteria are certain to be involved in the development:

Viruses:

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV): ( endemic ) Burkitt lymphoma , aggressive T / NK cell lymphoma, lymphomatoid granulomatosis ,

- Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1): adult (endemic) T-cell lymphoma / leukemia

- Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8): lymphoma of serous body cavities ( primary effusion lymphoma )

Bacteria:

- Helicobacter pylori (HP): A long-standing infection with HP can promote the development of low-grade NHL in the lymphatic tissue of the stomach ( MALT lymphoma ).

In quantitative terms, however, these cases only make up a relatively small proportion of all NHL.

Environmental factors

A case study from Sweden suggests that pesticides can be a possible trigger for the development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety commissioned an epidemiological case-control study on the aetiology of lymphomas. This states that chemical workers tend to be affected more than average. There is a clear connection with the use of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (dark hair dyes).

On March 20, 2015, a group of experts from the WHO, the IARC (International Agency for Research on Cancer) published a white paper that classifies five organophosphates as potentially carcinogenic. The herbicide glyphosate and the insecticides malathion and diazinon are classified as probably carcinogenic (group 2A) and the insecticides tetrachlorvinphos and parathion as possibly carcinogenic (group 2B). Malathion is suspected of promoting non-Hodgkin leukemia NHL and prostate cancer. Diazinon has also been shown to be associated with NHL and lung cancer. Surprisingly new is the classification of the herbicide glyphosate as a trigger for NHL leukemia, which is controversially discussed in specialist circles and on the part of manufacturers.

radioactivity

According to a study by the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus (now Belarus) from 1998, there was a demonstrable increase in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma as well as an increase in other types of cancer due to the reactor disaster in Chernobyl . This study is also relevant to people in other countries who have been exposed to increased levels of radioactive radiation.

Epidemiology

The current incidence in Germany (2014) is 19 to 23 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per year - the trend is currently still rising slightly. Men are affected by the NHL somewhat more frequently (+ 40% relative risk) than women. NHL can occur at any age, but overall more frequently in older people. * International sources indicate the incidence is significantly lower. AIDS patients have an incidence of NHL that is up to a thousand times higher.

Symptoms

- Usually not painful ("indolent") enlargements of the lymph nodes ("lymphadenopathy")

- Reduced performance, fatigue

- Possibly so-called " B symptoms " (fever> 38 ° C, night sweats, body weight loss> 10% within the last six months without any other explanation)

- Infection tendency and susceptibility to infection

- Blood changes (see below)

The following changes may be found in the blood tests:

- anemia

- Leukopenia or leukocytosis (caused by lymphoma cells in the blood)

- Thrombopenia

- Signs of inflammation ( blood sedimentation rate increased, α2 globulins and fibrinogen increased)

- Iron decreased, ferritin increased

- In B-cell lymphomas ( plasmacytoma , Waldenström's disease and others), monoclonal gammopathy may occur

- Often antibody deficiency syndrome

- Characteristic changes in certain serum parameters :

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) increased (with rapidly growing NHL or large NHL tumor mass) or with concomitant hemolytic anemia

- β2-microglobulin often but not always increased ( tumor marker for lymphoma diseases)

diagnosis

The diagnosis is made histologically using a biopsy of an affected lymph node. In addition to the histomorphological assessment, special staining techniques are used to accurately classify the biopsy material obtained. The currently valid WHO classification has largely replaced the Kiel or REAL ( Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms ) used previously .

Further examinations are necessary for the exact staging:

- Chest x-ray

- Ultrasound of the abdomen

- Computed tomography of the neck, thorax and abdomen

- Bone marrow puncture to obtain bone marrow histology and rule out bone marrow involvement

Accurate classification and staging is essential for targeted therapy.

Staging

Ann Arbor staging , developed in 1971 in Ann Arbor , Michigan , is in use worldwide today .

- Stage I: Involvement of a single lymph node region above or below the diaphragm

- Stage II: Involvement of two or more lymph node regions above or below the diaphragm

- Stage III: Involvement on both sides of the diaphragm

- Stage IV: Involvement of organs that are not primarily lymphatic (e.g. liver, skin, central nervous system)

Addition:

A = no general symptoms (fever, night sweats, weight loss)

B = with general symptoms

S = with spleen involvement (the spleen is treated like a lymph node in this stage division)

E = involvement outside of the lymph nodes and spleen.

Further parameters that serve to estimate the prognosis and represent clinical risk factors are summarized in the International Prognostic Index (IPI) .

therapy

Some NHL can now be treated curatively, i.e. with the prospect of complete healing. The chances of recovery depend on many different factors, for example the type of lymphoma, the age of the patient, the stage of the lymphoma (it seems plausible that a lymphoma that is only slightly widespread offers better treatment options than an already generalized one), and the patient's comorbidities and so on. As a very rough principle, it can be stated that highly malignant (ie rapidly growing) lymphomas can be treated well with chemotherapy and can also be completely cured. In contrast, low-grade (ie slowly growing) lymphomas cannot usually be cured with conventional radiation and chemotherapy, but they can still be treated well. The reason for this fact, which at first appears paradoxical, is that highly malignant lymphomas often divide and therefore grow very quickly, but precisely because of this they are very sensitive to treatments that attack the cancer cell when it divides (chemotherapy, radiation therapy). In indolent lymphoma, the lymphoma cells are significantly less sensitive to chemotherapy / radiation therapy, which disrupts cell division, and usually a certain proportion of the cells survive the treatment.

The therapy depends, among other things, on the Ann Arbor stage of the disease. In general, it can be said that irradiation is only useful in localized stages with a curative intention. In the case of indolent NHL in higher stages (from stage II), chemotherapy usually only has a palliative character, i.e. a complete cure is no longer possible. The choice of chemotherapy regimen naturally also depends on the patient's comorbidities. The therapy regimen of first choice for aggressive NHL is usually the CHOP regimen. The drugs cyclophosphamide ( C ), doxorubicin [Hydroxidaunorubicin ( H )], vincristine [Oncovin ( O )] and prednisolone ( P ) are used as combination chemotherapy. Increasingly, monoclonal antibodies are used in addition to chemotherapy [in B-NHL the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab (then the treatment regimen is appropriately referred to as R-CHOP )] or in the form of radioimmunotherapy ibritumomab-tiuxetan , as it has been shown to be the Improve prognosis in both high- and low-grade NHL. There are studies that show that in B-NHL, after completion of primary treatment, subsequent maintenance therapy with rituximab can help improve long-term results.

Overall, the rule applies that therapy should be given in centers with a lot of experience, as the therapy protocols currently change almost annually.

In order to regain a quality of life that is as unrestricted as possible in the long term after remission or healing, intensive counseling for patients and relatives about the often long convalescence period and the treatment of possible psychological and physical late effects is also important. In particular, the treatment of aggressive lymphomas with high-dose chemotherapy and radiation can have short-term and long-term side effects such as the development of fatigue , permanent damage to the immune system, the heart, unwanted sterility and intestinal problems in the form of radiation colitis . Some patients also experience a mostly temporary impairment of the ability to think, remember and cope with stress due to post-chemotherapy cognitive impairment (PCCI) (also chemotherapy-induced cognitive dysfunction or "chemo brain"), the cause of which, according to the current state of research, is either in the stressful illness itself , the direct physical effects of chemotherapy, or both factors.

| stage | low-grade lymphoma | highly malignant lymphomas |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Irradiation | IA: Radiation IB: Chemotherapy |

| II | possibly chemotherapy | chemotherapy |

| III and IV | chemotherapy | chemotherapy |

If a normal dose of chemotherapy cannot completely regress or if the patients suffer a relapse, high-dose chemotherapy combined with a stem cell transplant is another treatment option.

The need for a uniform classification of non-Hodgkin lymphomas

It has long been clear to clinicians and hematopathologists that NHL is a very heterogeneous group of diseases. Efforts have therefore been made to further classify the NHL. A uniform classification was necessary from various points of view and without clearly defined terms and disease entities it was almost impossible to compare the results of therapy studies and basic medical research. This made research into the causes of the disease and the optimal treatment options very difficult.

The first really useful classifications were:

Kiel classification

The Kiel classification refers in its name to the Christian-Albrechts-Universität Kiel , where it was developed by Karl Lennert in the early 1970s and revised in 1988.

The Kiel classification divides the NHL on the basis of microanatomical , enzyme-cytochemical and immunological properties. In addition, clinical experiences (more malignant, faster or more benign, slow course) were taken into account. Lennert and his colleagues differentiated the lymphomas into low-grade and high-grade . This division was based on cell size. The low-grade lymphomas consisted of cytic (rather mature) and a smaller proportion of blastic (very immature) cells, whereas high-grade lymphomas consisted mainly of blastic cells.

The Kiel classification became the binding classification for malignant lymphomas in Germany and was widely used throughout Europe . Lennert's student Lutz-Dietrich Leder had taken them apart in 1979. Over the years, the drawbacks became apparent:

- In the original classification from 1974, the "primarily extranodal lymphomas", i.e. the lymphomas that arise primarily outside of the lymph nodes (for example the so-called MALT lymphomas ), were not taken into account.

- The classification into “cytic” low-grade lymphomas and “blastic” high-grade lymphomas did not always correlate with the clinical course. Centrocytic lymphoma (later known as mantle cell lymphoma ) , for example, often showed an unfavorable clinical course, although it was classified as “low-grade” by the Kiel classification.

- Many special lymphoma diseases that were only recognized or discovered in the following years were not yet included in the original Kiel classification. In 1988 there was a major revision of the Kiel classification.

Kiel classification after revisions in 1988 and 1992: low-grade NHL

| Low-malignant B-NHL | Low-malignant T-NHL |

|---|---|

| Lymphocytic: B- CLL , B- PLL , hairy cell leukemia | Lymphocytic: T- CLL , T- PLL |

| Lymphoplasmocytoid lymphoma ( Waldenström's disease ) | Small cell cerebriform lymphomas: mycosis fungoides , Sézary syndrome |

| Centroblastic centrocytic (cb-cc) lymphoma | Angioimmunoblastic lymphoma (AILD), lymphogranulomatosis X |

| Centrocytic lymphoma | T-zone lymphoma |

| pleomorphic small cell T-NHL |

Kiel classification after the revisions in 1988 and 1992: highly malignant NHL

| Highly malignant B-NHL | Highly Malignant T-NHL |

|---|---|

| Centroblastic lymphoma | Pleomorphic medium and large cell T-NHL |

| Immunoblastic B-NHL | Immunoblastic T-NHL |

| Burkitt lymphoma | |

| Large cell anaplastic B-NHL | Anaplastic large cell lymphoma |

| Lymphoblastic B-NHL | Lymphoblastic T-NHL |

The so-called working formulation

In 1992 an initiative was launched in the USA with the aim of standardizing the various classification schemes that had previously been used. The resulting Working Formulation of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma for Clinical Usage , or Working Formulation (WF) for short , became the mandatory classification scheme for the NHL in the USA for the next few years.

WHO classification of malignant lymphomas

The WHO classification of the NHL by a group of experts from the World Health Organization is currently the most modern and widely accepted classification of the NHL, so it should be referred to whenever possible. However, older classification schemes are still in use. The classification of the NHL is still in flux. The WHO classification will also be revised in the future, as more and more detailed knowledge about the biology and pathophysiology of the NHL is gained.

The WHO classification (like the REAL classification) classifies NHL according to cytomorphological, immunological and genetic characteristics.

Precursor B-Cell Lymphomas

- Precursor B lymphoblastic lymphoma / leukemia

Mature B-Cell Lymphomas

- B-CLL / small cell lymphocytic lymphoma

- Hairy cell leukemia

- Plasmacytoma

- Extranodal MALT lymphoma

- Follicular lymphoma

- Mantle cell lymphoma

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- Burkitt lymphoma / leukemia

Precursor T-Cell Lymphomas

- Precursor T lymphoblastic lymphoma / leukemia

Mature T-Cell Lymphomas

- Mycosis fungoides / Sézary syndrome

- Peripheral T-cell lymphoma

- NK cell leukemia

- Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma

- Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, T / null cell type

See also

literature

-

Kiel classification

- K. Lennert , A. Feller: Histopathology of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas. 2nd Edition. Springer Verlag, New York 1992.

- K. Lennert, N. Mohri, H. Stein , E. Kaiserling: The histopathology of malignant lymphoma. In: Br J Haematol . 1975a; 31 (Suppl), pp. 193-203.

- K. Lennert, H. Stein, E. Kaiserling: Cytological and functional criteria for the classification of malignant lymphomata. In: Br J Cancer. 1975b; 31 (Suppl 2), pp. 29-43. PMID 52366 .

- Rappaport classification : H. Rappaport: Malignant lymphomas: nomenclature and classification. Tumors of the hematopoietic system. In: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC. 1966; 6, pp. 97-161.

-

Luke & Collins classification

- RJ Lukes, RD Collins: New approaches to the classification of the lymphomata. In: Br J Cancer . 1975 Mar; 31 Suppl 2, pp. 1-28. PMID 1101914 , PMC 2149570 (free full text).

- RJ Lukes, RD Collins: Immunologic characterization of human malignant lymphomas. In: Cancer. 1974 Oct; 34 (4 Suppl): suppl, pp. 1488-1503 PMID 4608683 .

- Working Formulation: The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Pathologic Classification Project. National Cancer Institute sponsored study of classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Summary and description of a Working Formulation for clinical usage. In: Cancer. 1982; 49, pp. 2112-2135. PMID 6896167 .

- REAL classification: NL Harris, ES Jaffe, H. Stein, PM Banks, JK Chan, ML Cleary, G. Delsol, C. De Wolf-Peeters, B. Falini, KC Gatter, TM Grogan, PG Isaacson, DM Knowles, DY Mason, HK. Müller-Hermelink, SA Pileri, MA Piris, E. Ralfkiaer, RA Warnke: A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. In: Blood . 1994; 84 (5), pp. 1361-1392. PMID 8068936 .

-

WHO classification

- E. Jaffe, NL Harris, H. Stein, JW Vardiman (Eds.): Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Haemopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. IARC Press: Lyon 2001

- H. Stein: The new WHO classification of malignant lymphomas. In: The Pathologist. 2000; 21 (2), pp. 101-105.

Web links

- Patient information from the “Malignant Lymphoma” competence network and search for treatment centers for high-grade and low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphomas

- Patient information on NHL in childhood ( April 10, 2015 memento on the Internet Archive )

- Detailed information on the subject of NHL in the case of additional HIV infection

swell

- ↑ Lennart Hardell, Mikael Eriksson: A case-control study of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and exposure to pesticides. In: Cancer. 85, 1999, p. 1353, doi : 10.1002 / (SICI) 1097-0142 (19990315) 85: 6% 3C1353 :: AID-CNCR19% 3E3.0.CO; 2-1 .

- ↑ BMU-2004-639: Epidemiological case-control study on the etiology of lymphomas. pdf

- ↑ Ibid., P. 124.

- ↑ IARC; Monographs Volume 112, evaluation of five organophosphate insecticides and herbicides: [1]

- ↑ Heise-Telepolis, "Cancer: Debate about Glyphosate": [2]

- ↑ Ministry of Extraordinary Situations of the Republic of Belarus, National Academy of Sciences of Belarus: Chernobyl Disaster: Consequences and Overcoming them, National Report 1998, (Russian).

- ↑ International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Study

- ↑ Cancer in Germany for 2013/2014. 11th edition Robert Koch Institute (Ed.) And the Society of Epidemiological Cancer Registers in Germany eV (Ed.). Berlin 2017

- ↑ Gerd Herold : Internal Medicine . Cologne 2007, p. 66 .

- ↑ Side effects and long-term effects in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Retrieved April 30, 2011 .

- ↑ Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich: Cancer and the "Chemobrain" - When the mental abilities of tumor patients suffer. Retrieved April 30, 2011 .

- ^ Treatment of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | DKG. Retrieved August 24, 2020 .