Congavata

| Drumburgh Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Concanata , b) Coggabata , c) Congavata , d) Concavata |

| limes | Britain |

| section | Hadrian's Wall |

| Dating (occupancy) |

Hadrianic , 2nd to early 5th centuries AD? |

| Type |

a) cohort fort, b) fleet station? |

| unit |

a) Cohors II Lingonum , b) Classis Britannica ? |

| size | Area: 96 × 82 meters, 0.8 ha (stone fort) |

| Construction |

a) wood and earth fort, b) stone fort |

| State of preservation | square floor plan with rounded corners, not visible above ground |

| place | Drumburgh |

| Geographical location | 54 ° 55 '40.4 " N , 3 ° 8' 55" W |

| Previous | Aballava Castle (east) |

| Subsequently | Maia Fort (west) |

Congavata (or Coggabata ) was a Roman auxiliary troop fort . It is located near the Solway Firth , in the parish (Parish) of Bowness, hamlet (Hamlet) Drumburgh, in the district of Allerdale , County Cumbria , England .

It belonged to the chain of fortresses of Hadrian's Wall (per lineam valli), which consisted of 16 forts, and secured its western sector. According to the Notitia Dignitatum , it was occupied by Roman troops until the early 5th century. The stone fort was the smallest of the ramparts in terms of area and is one of the archaeologically least known fortifications to date. Their remains are not visible above ground. The ground monument includes the remains of the fort, Hadrian's Wall and its facilities between Burgh Marsh and Westfield House.

Surname

The fort is mentioned in several ancient written sources. In the Notitia Dignitatum the fort appears as a Congavata , between the entries for Aballaba (Burgh-by-Sands) and Axeloduno (Netherby). The second source is the Staffordshire Moorlands Pan , on which the place is referred to as Coggabata .

According to Rivet / Smith, the Latin congavata or concavata means "hollowed out" or "hollow", perhaps a reference to the shape of the coastline or another natural feature. They also indicate that a Latin name is exceptional for a fortress in the ramparts region. It should nevertheless be derived from the Celtic. Canat stands for "steep hill" or "high and steep hill". Both terms, however, refer to the steeply sloping embankments in the nearby Bowness-on-Solway. There are no such hills or embankments at Drumburgh. The original place name was therefore probably correct Concanata .

The current place name arose from the amalgamation of the Gaelic Druim (= small round hill) and the Old English word Burh (= fortified place), which roughly means "small hill fortress".

location

Congavata was the fifteenth link in the fortress chain of Hadrian's Wall (vallum aelium) . It stood about 2.4 km north of the Stanegate , halfway between the Stanegate fort of Kirkbride in the southwest and the Burgh-by-Sands fort 6 km away in the east. The camp, like the neighboring fort at Bowness-on-Solway , was placed on a flat hill ( drumlin ) formed from glacial sediments on the edge of Burgh-Marsh, northwest of today's center. From there one had a good view on all sides of the surrounding plain, over the southern Sandwath Fjord of the Solway Firth , its coast and the mouths of Eden and Esk. The camp area is now partially built over. Congavata was connected to the nearest forts of Aballava and Maia at the western end of Hadrian's Wall via the military road. A presumed road branch east of the fort led to Stanegatekastell in Kirkbride. In the late 2nd century the ramparts belonged to the province of Britannia inferior , from the 4th century to the province of Britannia secunda .

Research history

The fort has been very little researched archaeologically and scientifically. The clergyman John Leland was in Drumburgh in 1539 and noted that “... mainly stones from the Pictwall were quarried to build Drumburgh, because the wall is very close.” A first smaller excavation at the fort and the wall was carried out in Performed by FJ Haverfield in 1899. He came across the remains of the stone fort (connection of the northwest corner with the wall). A more extensive dig was carried out in 1947 by Frank G. Simpson and Ian A. Richmond. It turned out that the stone fort was preceded by a somewhat larger wood and earth fort. The ceramic finds ranged from the 2nd century to the late Roman period. A prominent, right-angled moat west of Drumburgh-House was long thought to be a Roman defense moat. However, during the excavation of 1899 it turned out that it came from the Middle Ages. It testifies to the continuity of settlement in this place. In 1973 Dorothy Charlesworth investigated the course of the wall north of Glasson. During geophysical surveys, the wall line and the north trench to the northeast of Glasson were observed. A Roman altar (without an inscription) is set up in the garden of Drumburgh Castle. The Roman fortress and the section of ramparts around Drumburgh probably still contain many important archaeological finds. Further valuable information about the development of the northern British border system is expected for future excavations.

Inscriptions: Only three Roman inscriptions are known from Drumburgh, found in 1783, 1859 and 1883. These were building inscriptions, so-called "Slab-Stones", on which two cohorts are named that were used for the construction of individual sections of the wall, defenses or Buildings were responsible. They came either directly from the fort or from Hadrian's Wall.

development

In 122, Emperor Hadrian ordered a barrier wall to be built in northern Britain, reinforced by watchtowers and forts, from the Tyne to the Solway Firth, to protect the British provinces from the constant incursions of the Picts from the north. Most of the wall was built by soldiers from the three legions and men of the Classis Britannica stationed in Britain .

Little is known about the history of the fort. The crew stationed here was supposed to secure the southern endpoints of the two fjords of the Solway (Stonewath and Sandwath), an incursion route often used by looters from the tribes of the Selgovae in the north and possibly also the Novantae in the northwest. The wood and earth fort was probably built at the same time - 122 to 125 - as the Segedunum camp at the eastern end of the wall. When it was converted into a stone fort is not known, this may not have happened until around 160. The ceramic finds date back to the years 367–369. The camp was believed to have been in use until the late 4th or early 5th century. There are no visible remains. Since there are no large stone deposits in the immediate vicinity, the building material of the camp and the wall was probably used in its entirety for the buildings that were built later, e.g. B. Drumburgh Castle a fortified farmhouse (Bastle House) with Roman altar stones as garden decoration.

Fort

The fortification went through two construction phases during its period of use, a wood-earth and a stone construction phase. The area of the early wood and earth fort is likely to have been somewhat larger than the stone fort. The latter measured 82.5 (north-south) × 96.5 meters (west-east). Its longitudinal axis was oriented to the NE, it had the rectangular floor plan with rounded corners (playing card shape) typical of mid-imperial facilities. With an area of only 0.8 hectares, the stone camp (next to that of Newcastle ) was by far the smallest wall fort. The excavation in 1899 showed that it was built directly onto Hadrian's Wall or that it formed the north wall of the fort. Its foundations were about 3 meters wide. It is not known whether it also had the square intermediate and corner towers attached to the inside, which were typical of medieval camps. The fort probably also had the interior buildings that were standard for auxiliary troop camps in the Middle Imperial period: in the center the headquarters (principia), one or two granaries ( horrea ) and staff barracks (centuria). The main street of the camp (via principalis) connected the west and east gates. In the northwest corner, the excavators came across a wall that was supported on the west side with three pillars ( pilasters ), presumably it belonged to a warehouse that - remarkably - had been attached directly to the north wall. Behind the northwest corner was a ramp made of mud. Access to the fort was possible through three gates (west, east and south). It is unclear whether they were additionally reinforced by flank towers. As is customary with most of the medieval castles, they were not placed centrally. The south gate was located near the SE corner, the west and east gate next to the NW and NE corner. It is not known whether the camp also had a north gate. The west gate had obviously been blocked by a palisade in front . When this happened is unknown. The curve of the main street in Drumburgh, which runs almost at a right angle to the northeast, marks the southwest corner of the fort. Perhaps the fort also had a small port on the Solway coast.

Hadrian's Wall

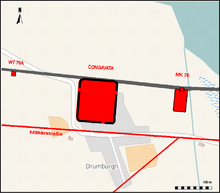

To the west of Burgh-by-Sands, Hadrian's Wall reaches the coastal plain on the Solway Firth. A lock was unavoidable here in particular, as otherwise intruders would be able to wade or swim through the relatively shallow Solwayfjords at low tide or when the water level was low. Nothing can be seen of the wall itself there today. Until the 19th century it is said to have been preserved up to a considerable height. The wall probably always ran close to the south bank of the Solway. So far, however, no remains have been observed there. Congavata was located in the middle between the mile fort 76 in the east and the watchtower 76A in the west. During the excavations of 1899, a section of wall between the Burgh Marsh and the fort was examined more closely. There it was 2.95 meters wide. The north trench reached a width of 8.9 meters. The berm was also about 8 meters wide. Today's motor road west of Drumburgh, between Mile Fort 77 and Watchtower 78B , runs directly over the foundations of the wall.

From the south ditch (vallum) you can see a few short stretches in the fields northeast of Cottage and Glendale Holiday Park, halfway between Drumburgh and Bowness-on-Solway and south of Port Carlisle. The 1973 excavations and geophysical surveys also confirmed the course of the rampart and trench north of Glasson. The exact course of the military road , however, could not be confirmed archaeologically. It is believed that it ran parallel to the wall or a few meters away from it. She followed her line pretty exactly to Bowness. The Vallum, however, probably took a much more direct route.

garrison

Congavata was probably occupied by regular Roman soldiers from the middle of the 2nd to the beginning of the 5th century at the latest. Legionnaires may also have stayed in the camp temporarily. They were usually not assigned to garrison service on the border, but sent special forces for the more demanding construction projects on Hadrian's Wall. A complete cohort (around 500 men) could not be accommodated in this camp. There were probably no more than 250 men there. Most of the unit was probably stationed in Kirkbride on Stanegate or in neighboring Bowness. In late antiquity, the occupation belonged to the Limitanei .

Which units were stationed in Congavata between the 2nd and 3rd centuries is unknown due to a lack of written sources. Two building inscription fragments from the area around Drumburgh name a Coh (ors) VII and Coh (ors) VIII (see inscriptions). It is unclear whether they were part of a legion or auxiliary force. In the 4th century AD, according to the Notitia, a Gallic auxiliary troop unit, the Cohors secundae Lingonum (the second cohort of Lingons ), occupied the fort. Their soldiers were originally recruited in the province of Lugdunensis I , in the area around the French city of Langres , the Civitas Lingonum . No other epigraphic evidence has yet been found for their stationing at Drumburgh. At that time she was commanded by an officer in the rank of tribune and belonged to the army of the Dux Britanniarum . Since the troop is still mentioned in the Notitia, which was created in the late 4th century, it could have stood there until the final withdrawal of the Roman army from Hadrian's Wall.

Vicus and burial ground

Whether there was a civil settlement ( vicus ) or a burial ground in the vicinity of the fort is unknown due to the lack of relevant finds. Only a few Roman wells were found south of the main road.

See also

literature

- J. Collingwood Bruce: Roman Wall, Harold Hill & Son, 1863, ISBN 0-900463-32-5 .

- RG Bruce, I. Richmond: Handbook to Roman Wall, 12th Edition, 1966.

- Hadrian's Wall Map and Guide by the Ordnance Survey, Southampton, 1989.

- Robin George Collingwood, RP Wright: The Roman Inscriptions of Britain, Oxford 1965.

- RSOTomlin, MWC Hassall: Roman Britain in 2003 (III. Inscriptions); Britannia, 35, 2004.

- Geophysical Surveys of Bradford, Report on Geophysical Survey: Hadrian's Wall, 1991.

- FJ Haverfield: Report of the Cumberland Excavation Committee 1899. Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society, 1900, p. 85.

- FG Simpson, IA Richmond: The Roman fort at Drumburgh. Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society, 1952.

- DR Wilson: Britannia in Roman Britain, 1973, Vol. 5, 1974, p. 412.

- Eric Birley: Research on Hadrian's Wall, 1961.

- Guy de la Bédoyère: Hadrian's Wall: history and guide, Tempus, 1998, ISBN 0-7524-1407-0 .

- Albert Rivet, Colin Smith: The place-names of Roman Britain, 1979.

- Nick Hodgson: Hadrian's Wall 1999-2009.

- Tony Wilmott: Hadrian's Wall: Archaeological research by English Heritage, 1976-2000, 2009, p. 48.

- Frank Graham: The Roman Wall. Comprehensive History and Guide, Frank Graham 1979, ISBN 0-85983-140-X .

- John Collingwood Bruce: The Roman Wall: A Description of the Mural Barrier of the North of England, 1867, with numerous pictures of wall remains, altars, inscriptions etc.

Remarks

- RIB = Roman inscriptions in Britain

- ↑ Tomlin / Hassall 2004, pp. 344-345, R & C 153, Rivet / Smith 1979, p. 315, Hodgson 2009, p. 156.

- ↑ Eric Birley 1961, pp. 209-211, Simpson / Richmond 1953, pp. 9-14, RIB 2051 , RIB 2052 RIB 2053 (possibly from 369 AD)

- ↑ Eric Birley 1961, pp. 209-211, Simpson / Richmond 1953, pp. 9-14, RG Collingwood 1923, pp. 3-12.

- ^ RJ Bruce 1966, p. 204.

- ↑ Guy de la Bedoyere 1998, p. 116.

- ^ ND Occ. XL, 31, Tribunus cohortis secundae Lingonum Congavata RIB 635 , RIB 798 , RIB 800

- ↑ Eric Birley 1961 pp. 209-211, Simpson / Richmond 1953, pp. 9-14.

Web links

- RIB Roman Inscriptions of Britain inscription database

- Concavata on ROMAN BRITAIN

- Concavata Castle on PASTSCAPE

- Concavata Castle on HISTORIC ENGLAND

- Part XI on You Tube, The Wall from Arbeia to Maia. Film production with 3D-CGI models, images and explanation of the individual Roman castles along Hadrian's Wall (English).

- Stanwix to Bowness on CastelsFortsBattles

- Location of Roman monuments on Vici.org.

- Hadrian's Wall photo album on Flickr