Dome crane

The Cologne Cathedral crane was a wooden slewing crane that had stood on the south tower of Cologne Cathedral under construction since the 14th century . The crane, which is more than 25 meters high, was only in use for around 50 years, but it shaped the Cologne cityscape as a landmark for a period of more than 500 years. It was only dismantled in 1868.

Time of erection

In the past, the time around 1400 or even around 1500 was assumed for the construction of the cathedral crane. Such a late point in time is not compatible with the results of more recent research on the architectural history of Cologne Cathedral. The excavation find of a gold coin from 1357 suggests that the foundations of the outer walls of the south tower were ready at that time. The former Cologne cathedral builder Arnold Wolff assumes that the crane was erected only a little later. With the state of construction when work on the south tower was discontinued around 1410, there would hardly have been any possibility of longer use of the crane at the site at that time, as it could only be used a little beyond the second floor of the tower due to its dimensions. However, it would have been possible to change the position of the crane slightly and also use it for the construction of the two upper floors of the tower.

technology

Due to their design, early cranes of the Middle Ages could only move the loads vertically. The horizontal transport to the site required additional lifting and transport equipment. The Cologne cathedral crane could not only operate one point, but also describe a circular path with the load. In addition, the length of the rope from the tip of the jib to the place where the load was deposited was around twenty meters. This made it possible to pull the load several meters out of the vertical with thin ropes. The crane's range of action was therefore a circular ring . He was able to reach all areas of the masonry on the south tower, with the exception of the places where he rested. This not only avoided transports to the construction site. The scaffolding could also be built much lighter, as it only had to be carried by the workers and not heavy workpieces.

Construction and dimensions

The dome crane, which was 25.10 meters high from the base to the tip of the jib, consisted of a slate-clad supporting structure made of approximately 30 by 30 centimeter thick oak beams. The framework formed a 12.80 meter high truncated pyramid with a square base. At the base, the crane frame had a side length of 9.73 meters, which decreased to 4.70 meters at the top. At the bottom, at right angles to the bars of the frame, there were two oak bars with normal dimensions and - crossing them - a 62 by 62 centimeter beam placed on the frame.

In the center of the scaffolding was an upright, 15.20 meter long, round oak beam known as the " Kaiserstiel ". It was almost a meter in diameter at the top and tapered down to about 33 centimeters. It towered over the truncated pyramid of the supporting frame by 5.40 meters and was clad there with an octagonal hood that was not connected to the base. The “Kaiserstiel” was held at the bottom in a basket made of four wrought iron ribbons, each 1.65 meters long, by a pear-shaped spike with a diameter of 15 centimeters. The mandrel in turn rested in an iron bearing shell on the girder so that the “Kaiserstiel” could easily be rotated. In addition to the requirements of the construction company, the ability to rotate also met the requirement for less susceptibility to storms, since the crane boom could rotate with the wind and thus offered less surface.

The structure of the cathedral crane was erected on a square frame made of oak beams. Up to the second floor, the south tower of the cathedral has two windows on each side, which are separated from each other by masonry. The dome crane rested with the corners of the frame on these four wall sections so that the corner pillars of the tower remained accessible. The figure of the square inserted into a square and rotated by 45 degrees results in an edge length of the inner square of about 9.61 meters with the width of the tower walls of 13.60 meters. The cathedral crane had a side length of 9.73 meters at its base.

At the upper end, which protruded over the covered crane frame, three oak beams were mounted on the "Kaiserstiel", which were led out of the hood and with further beams as struts formed the crane boom. The boom had a length of 13.15 meters. It towered over the hood in the vertical by 7.20 meters and stepped 10.55 meters horizontally out of the "Kaiserstiel". When work on the south tower was stopped, the tip of the boom was around 70 meters above the ground.

transport

Arnold Wolff suspects that the crane was built at the foundation level and that it moved up with it during the construction of the south tower. To do this, one corner of the crane was first driven up a bit with wedges and lined with blocks. Then the three other corners followed, until after a few repetitions with 35 to 55 centimeters the height of a new stone layer was reached and the crane could be set down. At a height of 45 meters above the ground and an estimated construction time of 50 years, the cathedral crane only had to be lifted about every six months.

drive

There is no reliable record for the drive of the dome crane. A drawing by Jan van Eyck from 1437 shows a tower with an attached construction crane as a background motif. Behind the windows of the tower you can see a man in a treadmill that drives the crane. However, it is not certain that the image shows the south tower of Cologne Cathedral.

In 1926 a picture was published in a newspaper showing the inside of the cathedral crane. There were two pedal bikes attached to it. It is not known what this representation was based on. A construction drawing of the crane made by an employee of the Dombauhütte when the crane was dismantled does not contain any reference to such installations. There are also no documents on this in the cathedral building archive of the Cologne cathedral building administration .

Numerous images of other construction cranes from the Middle Ages have survived, and some pedal bikes have survived to this day. There are cranes with internal or external treadmills as well as those that were driven by treadmills placed further away. For the Cologne cathedral crane, the drive is most likely kept with one or two treadmills, which were either in the crane housing or just a little below the crane.

A hand-operated winch had to be installed for the one-time commissioning during the celebration of the laying of the foundation stone for the further construction of the cathedral on September 4, 1842, as the old drive was no longer available.

power

The assertion has repeatedly been made that the Cologne cathedral bells were lifted into place in the belfry of the south tower with the cathedral crane. That seems impossible. The cathedral crane was on the south tower and had no way of lowering the bells into the tower from above. With weights of several tons - more than ten tons for the Pretiosa - the crane was not designed for their transport. The largest stone blocks visible from the outside of the south tower weigh a little more than 1000 kilograms. A possible load weight of a maximum of one and a half tons is therefore assumed for the crane.

For the south tower, around 20,000 tons of stones were moved during the fifty years of construction. That corresponds to two to three tons of material or six to eight material movements every working day. One stroke lasted about 20 minutes.

Rope and sling

Taking into account the path from the ground to the top of the crane and along the boom through the crane frame to the drive, the final cable length required is around 100 meters. Since pulley blocks with safety and loose pulleys were probably not used, the rope will not have been much longer.

The medieval cathedral construction huts used different slings . The most common was the stone tongs , for which holes first had to be driven in on opposite sides of the stone to be transported. The traces of such processing should be visible on the stone surfaces on the outside; however, they are missing from the south tower of Cologne Cathedral. Slings that only needed a hole to anchor in the stone were the two- or three-part large and small wolf , as well as the scissor-shaped spreader wolf.

Traces of processing were discovered on stones in the buttress of the choir and on the south side of the nave, which made it possible to reconstruct the tools used. It is the spreader, which consisted of two crescent-shaped metal parts that were connected in the middle by a bolt. The spreader grinder was inserted into dovetail-shaped holes on only one side of the goods to be transported and was firmly connected to the workpiece when the load was pulled up. Although no traces have been found on the stones of the south tower for this tool either, it is assumed that it was used here in different sizes for stones of different weights.

Repairs and changes

The cathedral crane was repeatedly repaired after the construction work on the south tower was completed around 1410 and after the entire cathedral construction was discontinued around 1525. Initially, the repairs served to maintain the operability, in later centuries also to preserve a landmark of the city.

- In 1606 and 1610, repair work was carried out on the cathedral crane, which had long since been shut down.

- In 1693 the top of the crane was destroyed by a lightning strike and repaired.

- In 1816, the Prussian secret building officer Karl Friedrich Schinkel received from King Friedrich Wilhelm III. the order to assess the structural condition of Cologne Cathedral. On April 18 and July 10, 1816, a delegation led by Schinkel inspected the cathedral, and the cathedral crane was also checked. Due to dangerous damage to the material, the boom was completely dismantled between July 11 and July 22, 1816. This measure provoked vigorous protests from the Cologne population. The assembly of a new boom was refused for reasons of cost. The last mayor of the imperial city, Reiner Josef Klespe (1744-1818), bequeathed an amount of 1,800 Reichstalers for this purpose. In addition, the city council held a collection.

- On September 11, 1819, “a new beak 55 feet long and at the lower end 17 feet wide” was installed on the cathedral crane.

- As early as 1828, the poor workmanship of the newly attached boom required repairs.

- In 1842 the cathedral crane was to be used symbolically as part of the laying of the foundation stone for the further construction of the cathedral. The cathedral builder Ernst Friedrich Zwirner thought the existing arm was too weak and had it replaced in the summer of 1842, with a counterweight being attached.

- For the one-time commissioning on September 4, 1842, a hand-operated winch was installed because the medieval drive was no longer available.

- Between 1842 and 1853 the counterweight of the boom was removed again; it is no longer present in the oldest photographs of the cathedral from 1853.

Duration of use

middle Ages

Construction of the south tower is assumed to begin between 1355 and 1360. Around 1410 work was stopped here, only the nave continued until around 1525. This means that the cathedral crane was only in use for about fifty years in the Middle Ages.

Modern times

On November 23, 1840, the royal cabinet order was issued to found the Central Cathedral Association and to continue building the cathedral. On September 4, 1842, the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV. And the archbishop coadjutor Johannes von Geissel laid the foundation stone for the construction of the cathedral. For the occasion, the cathedral crane was decorated with numerous flags and a Prussian eagle carved from wood at the tip of the boom. The symbolic first sandstone cuboid for further construction was lifted onto the south tower with the cathedral crane. It still bears the carved inscription to this day

"IN MEMORIAM / CONTINUATAE / AEDIFICATIONIS / POSITUS // AD MDCCCXLII / DIE IV SEPT"

"Set in memory of the continuation of construction on September 4, 1842"

In 1868 this stone block with the weathered upper area of the south tower was removed again and relocated in 1871. On this occasion a second inscription was carved into the stone:

“CARCHESIO VERSATILI / REMOTO IN SUUM NUNC / LOCUM VAPORUM OPE / REPOSITUS / AD MDCCCLXXI / THE XXIII MAY”

"After the removal of the slewing crane with steam power, returned to its current location on May 23, 1871"

Dismantling

After the decision to continue building Cologne Cathedral, restoration work began in 1823 and construction work began on the cathedral construction site in April 1824. Up to the 19th century, the advancement of technology had produced subsidies that were superior to the cathedral crane in many ways. In 1867, three hand-operated winches, each with six workers, were in use on the north tower, with which 36 stones could be lifted up the tower every day - four to six times the capacity of the medieval cathedral crane. A steam engine was operated from October 1869 , which further shortened the lifting times. Heavy transfer cars that ran on railroad tracks were in use at the height.

When building the cathedral towers from 1845, the intention was to first build the north tower up to the height of the south tower. Then both towers should be built parallel higher up. The scaffolding on the north tower reached the height of the south tower in 1867. The cathedral crane now stood in the way of further construction and had to be removed. On February 29, 1868, the carpenters began dismantling the cathedral building. In the 58th construction report of the Dombauhütte from May 1868 it says:

“After the slate-covered outer board cladding of the crane housing had been removed, the wooden parts dating from the 15th century were so damaged that the whole construction had to be supported before the pieces of bandage could be broken off. The fir beams and struts added in 1825 during a thorough restoration of the cathedral crane had suffered greatly over the course of time due to inadequate maintenance of the slate roofing of the crane housing, and a longer preservation of the cathedral crane could only have been achieved through a total renovation.

March 13th c. The 43-foot long boom of the crane, which was newly manufactured in 1842, was lifted and the rotary axis was soon lifted out of the ladle store and the trusses were laid down with great care, as the trunks of oak were up to 3 feet thick and 50 feet long were so destroyed by worm damage and rot that they broke through their own burden when lying down. This work of removing the canopy, which is so dangerous given the great height, the poor wood material and the prevailing wind, was carried out by the cathedral carpenters under the direction of the cathedral carpentry from Amelen without any accident (...). "

At the end of March 1868 the dismantling of the cathedral crane was finished. Of its components, only the wrought-iron mandrel with its basket has been preserved in its original form, on which the “Kaiserstiel” and thus the entire weight of the crane and the loads it carried rested. Today it is in the model chamber of the cathedral building .

The wood from the dismantled crane was used to make various items:

- A crucifix about 86 centimeters high, made in the style of historicism , is in the cathedral archive.

- A lecture cross of the parish of St. Mariä Himmelfahrt in the Cologne district of Holweide is to be made of the wood of the cathedral crane.

- Several angel heads.

- Multiple consoles. A console with carved acanthus leaves and the Prussian coat of arms under a crown is located at Stolzenfels Castle . It bears an inscription that refers to the cathedral crane.

- A turned penholder that was made for the architect Karl Hecker. He gave it to his son, the philologist and Goethe researcher Max Hecker , when he left Cologne in 1900 to go to Weimar.

- Lions as coat of arms holder.

- A figure of an upright lion, apparently the top of a stair post.

- Two grand armchairs for the Senate Hall of Cologne City Hall, which were set up in the Hansa Hall at a later date and are no longer preserved.

- Eight upholstered and richly decorated armchairs. It is assumed that the chairs were made shortly after the cathedral crane was dismantled, first used in the town hall and finally given away to deserving citizens. One of these chairs was given to the Cologne entrepreneur couple Friedrich August and Therese Herbertz after 1880 in recognition of their civic engagement. Herbertz's extensive support in preparing the historical pageant to complete the cathedral was probably one of the reasons. The chair was then owned by the family and appears to be the only surviving copy. It was donated to the cathedral building archive in 2010.

- Several models of the cathedral crane, some of which could be used as tobacco boxes. Like the original, the 27 centimeter high models have a rotatable upper part with an arm. An inscription is carved on the base: model from the wood / of the domkrahnen zu / coeln erected at 1500 / det. on March 13, 1868. One of these models is in the Cologne City Museum , one in the cathedral building administration and another privately owned.

After purchasing one of the models of the cathedral crane in 1974, the then cathedral master builder Arnold Wolff had a dendrochronological examination carried out. The wood examined had grown by 1827, so it was used for the wood model of the boom that was newly attached in 1842. The wood of the crane, which originated in the Middle Ages, was probably too rotten to be used again.

reception

Cologne population

The cathedral crane was a defining element of the Cologne cityscape for over 500 years. In addition, it was a symbol for the Cologne population that the cathedral building was by no means abandoned, but only interrupted. This also explains the protests of Cologne citizens when, in 1816, by order of Prussia, the jib had to be removed from the cathedral crane, which was apparently always operational. The cathedral crane was a part of everyday life for citizens. The people of Cologne looked at the cathedral crane to read the wind direction; when the crane turned in the wind during the night, a characteristic sound penetrated the whole city. A contemporary witness complained after the cathedral crane was dismantled that it was bad to see it during the day, but to not hear it during the night was unbearable.

The document with the signatures of the emperor and numerous other princes and secular dignitaries, which was embedded in the keystone of the finial of the south tower on October 15, 1880, made reference to the cathedral crane: abandoned and abandoned to decay, the cathedral cranes towered over three centuries, the old landmark of Cologne, the miracle building sinking into ruins. The following day a historical pageant took place, during which numerous decorated floats and citizens dressed in historical costumes marched past the cathedral courtyard at the Kaiser. One of the floats carried a replica of the cathedral crane.

Visual arts

painting

The drawing Saint Barbara made by Jan van Eyck in 1437 shows Barbara of Nicomedia in front of a tower under construction as an attribute . The tower shown is similar to the south tower of Cologne Cathedral; However, it has not been proven that this served as a template. At the top of the picture you can clearly see a construction crane through which a stone block is being lifted upwards.

Later representations can be clearly identified as part of city views, by their lettering or by a traditional title as images of the cathedral crane on the south tower of Cologne Cathedral. The unmistakable silhouette of the cathedral crane served as a symbol of the city of Cologne in its time, as are the twin towers of Cologne Cathedral today. This is shown as works of Christian art by two panels of the Little Ursula Cycle, created between 1455 and 1460 by unknown artists from the Cologne School of Painting : Arrival in Cologne and St. Ursula's Dream and Arrival in Cologne and Martyrdom. On the foundation picture donated in 1621 in the pilgrimage church of the painful Mother of God in Bödingen , the silhouette of the cathedral crane marks the city of Cologne, which is shown far away on the horizon.

From the 17th century onwards, the unfinished Cologne Cathedral with the cathedral crane was a popular motif in vedute painting . Examples are the picture of a street with the cathedral in the middle by Jan van der Heyden from 1684 and a 1798 view of the cathedral square by Laurenz Janscha .

Chronicles and cityscapes

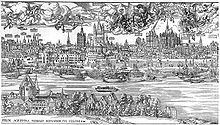

Various chronicles from the 15th and 16th centuries show the cathedral crane on the south tower of the cathedral as part of the city panorama. The Fasciculus temporum of Werner Rolevinck was created in 1483, the Schedelsche Weltchronik 1493 and the Koelhoffsche Chronik 1499. The Koelhoffsche Chronik contains as a chronicle of the city of Cologne several representations with the crane as a landmark of the city.

The cityscapes that emerged in the 16th century show, in comparison to the earlier works, the efforts of the artists to achieve a realistic representation. Examples are the woodcuts of the Cologne cityscape from 1531 by Anton Woensam and the Cologne cityscape from 1570 by Arnold Mercator . An engraving after Wenceslaus Hollar from 1636 clearly shows the possibilities of the advanced printmaking.

19th century documents

With the graphics of the 19th century and early photographs, up to the month of dismantling in March 1868, the documentary aspect came to the fore. Large-circulation views of the unfinished cathedral, with the cathedral crane on the south tower, played an important role in the advertising of the Central Cathedral Association in Cologne, which was founded in 1840 . They were still issued decades after the crane was dismantled, especially as members' gifts of the Zentral-Dombau-Verein. Since the first issue on September 4, 1842, the motif can also be found on some of the cathedral building medals issued by the Cathedral Building Association .

Contemporary literature (selection)

In the course of the growing enthusiasm for the further construction of Cologne Cathedral, the poet Max von Schenkendorf wrote his poem Before the Cologne Cathedral in 1814 or a little later . In the first stanza he took up the opinion that was widespread among the Cologne population that the construction of the cathedral was only interrupted:

I still see

old Krahn raised on the roof, It

just seems to me that the work has been postponed,

Until the right masters approach.

Johanna Schopenhauer toured the Rhineland and Belgium in 1828 and also visited Cologne. She wrote about the removal of the crane boom a few years ago at the time of her visit:

“The whole of Cologne started moving when a few years ago, during the repair of the noble building, which had only become necessary, the cranes, which had been standing for centuries, were taken down from the only half-finished tower, and the people did not rest until they were back at their old one Saw that it is by no means a special ornament. "

The later revolutionary and US-American politician Carl Schurz described in his memoirs the sight of Cologne Cathedral, which he passed on his way to school around 1840:

“The Cologne Cathedral, which now stands there in all the glory of its completion, looked like a magnificent ruin at that time. Only the choir was fully developed. The middle section between the choir and the towers was poorly roofed, for the most part still in external brick walls, and of the two towers themselves one rose a little more than sixty feet above the ground, while the other carried the centuries-old, world-famous crane , maybe three or four times that height. The ravages of time had gnawed the artful chisel work mutilating in many cases, and so they looked, unfinished and yet already weathered, senile and sad down on the living generation. "

Herman Melville visited Cologne in 1849 while on a trip to Europe. In his diary he wrote of "the famous cathedral where the everlasting crane stands on the tower." In his work Moby-Dick , published in 1851 , Melville let the narrator Ismael close the 32nd chapter - an excursus on cetology - with the following words :

“But I now leave my cetological system standing thus unfinished, even as the great Cathedral of Cologne was left, with the crane still standing upon the top of the uncompleted tower. For small erections may be finished by their first architects; grand ones, true ones, ever leave the cope-stone to posterity. God keep me from ever completing anything. This whole book is but a draft nay, but the draft of a draft. Oh, Time, Strength, Cash, and Patience! "

“But now I'm leaving my cetological system in the lurch, as unfinished as the sublime Cologne Cathedral was left, with the crane still on the platform of the unfinished tower. Because small structures can be finished by whoever planned them first; the big ones, the real ones, however, always leave it to posterity to insert the keystone. God keep me from ever accomplishing anything. This whole book is just a draft - oh, just a draft of a draft. Oh! Time, strength, money, patience. "

literature

- Klaus Hardering: From magnificent lançades, a feast for Empress Augusta and a chair made from the wood of the old cathedral crane. In: Kölner Domblatt , 2010, 75th episode, pp. 86-103, ISBN 978-3-922442-69-1 .

- Franz Theodor Helmken: The Coeln Cathedral, its history and construction, sculptures and art treasures. Fourth revised and supplemented edition. J. & W. Boisserée, Cologne 1899, digitized .

- Ernst Heinrich Pfeilschmidt : History of the Cologne Cathedral. Kersten, Halle ad Saale 1842, digitized .

- Arnold Wolff : Timeline of the history of the Zentral-Dombauverein and the cathedral construction since 1794. In: Kölner Domblatt , 1965/1966, 25th episode, pp. 13–70.

- Arnold Wolff: The Cologne cathedral crane. In: Kölner Domblatt, 2010, 75th episode, pp. 66–85, ISBN 978-3-922442-69-1 .

Web links

- The cathedral crane , website of the Cologne City Museum , with images of an armchair and a model of the cathedral crane made from the wood of the boom.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, p. 71.

- ↑ a b c d Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, p. 74.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 80–81.

- ^ A b c Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, p. 73.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, p. 75.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 70–71.

- ^ A b Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ a b c d Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, p. 81.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 76-77.

- ^ A b Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Dankwart Leistikow: Lifting devices for stone in medieval construction: Wolf and tongs. In: Architectura. Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Baukunst, 1982, Volume 12, pp. 20–33, ISSN 0044-863X .

- ^ Dankwart Leistikow: Medieval hoists on Cologne Cathedral. In: Kölner Domblatt 1983, 48th episode, pp. 183–196, ISBN 3-7616-0731-8 .

- ↑ a b c d Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, p. 82.

- ^ Franz Theodor Helmken: Der Dom zu Coeln, p. 19.

- ^ Karl Friedrich Schinkel : Official report on the structural condition of Cologne Cathedral. Excerpt from: August Reichensperger : The Christian-Germanic architecture. Third revised edition. Ms. Lind'sche Buchhandlung, Trier. 1860, digitized .

- ^ A b Ernst Heinrich Pfeilschmidt: History of the Cologne Cathedral, p. 90.

- ^ A b Franz Theodor Helmken: Der Dom zu Coeln, pp. 24-25.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, p. 68.

- ^ Ernst Heinrich Pfeilschmidt: History of the Cologne Cathedral, p. 118.

- ↑ a b c d Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, p. 70.

- ↑ Arnold Wolff: Timeline for the history of the Zentral-Dombauverein, p. 17.

- ↑ a b Arnold Wolff: Timeline for the history of the Zentral-Dombauverein, p. 42.

- ↑ Arnold Wolff: Timeline for the history of the Zentral-Dombauverein, p. 43.

- ↑ Richard Voigtel: 58. building report. In: Kölner Domblatt No. 273 of June 30, 1868, pp. 2–4, here p. 3, online PDF 4.3 MB.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, p. 78.

- ↑ a b c d e f Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ a b c Klaus Hardering: From splendid Lançaden, p. 102.

- ^ A b Robert Boecker: Carved from historical wood. In: Church newspaper for the Archdiocese of Cologne, Jul 16, 2010, No. 28, pp. 10–11, ZDB -ID 558595-8 .

- ↑ Klaus Hardering: From splendid Lançaden, pp. 101-102.

- ↑ a b c Klaus Hardering: From splendid Lançaden, p. 101.

- ↑ Klaus Hardering: From splendid Lançaden, pp. 99-100.

- ↑ Klaus Hardering: From splendid Lançaden, pp. 102-103.

- ^ A b Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, p. 67.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, p. 84.

- ↑ Klaus Hardering: From splendid Lançaden, p. 94.

- ↑ Klaus Hardering: From splendid Lançaden, p. 100.

- ^ Ernst Heinrich Pfeilschmidt: History of the Cologne Cathedral, p. 111.

- ^ Arnold Wolff: Der Kölner Domkran, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Max von Schenkendorf: In front of the Cologne Cathedral. In: Max von Schenkendorf: Complete Poems. Gustav Eichler, Berlin 1837, pp. 352–353.

- ^ Johanna Schopenhauer: Excursion to the Lower Rhine and Belgium in 1828. FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1830, digitized .

- ^ Carl Schurz : Life memories of Carl Schurz up to the year 1852. Georg Reimer, Berlin 1906, p. 61, digitized .

- ↑ Herman Melville : Moby-Dick; or, The Whale. Constable and Company, London 1922, p. 179, digitized .