Euthydemos

The Euthydemos ( Greek Εὐθύδημος Euthýdēmos ) is an early work by the Greek philosopher Plato , written in dialogue form . The content is a fictional conversation between Plato's teacher Socrates and the sophist Euthydemus , after whom the dialogue is named, his brother Dionysodorus, Socrates' friend Ktesippus and the young man Kleinias.

The subject is the art of argument ( eristics ) practiced and taught by the sophists and their relationship to philosophy. At the request of Socrates, Euthydemus and Dionysodorus demonstrate the eristic art of debate based on fallacies . The aim is not to find the truth, but only to win over the opponent, whose views are to be refuted by all means. The eristic discourse means struggle; it contrasts with Socrates' philosophical search for truth, which is a common, friendly striving for knowledge.

The dialogue leads to an aporia , an apparently hopeless situation: the eristics is exposed as unsuitable, but it does not succeed in developing a coherent philosophical alternative for the time being. Only the way to such an alternative can be seen more clearly.

In modern research, the playful, humorous and comedic aspect of the work is emphasized and the literary brilliance is appreciated. The question of the extent to which Plato also wanted to emphasize a serious philosophical concern is answered differently. In the history of philosophy, the Euthydemos is significant as a source for the early history of ancient logic . It is also the oldest surviving work in which protreptic , the introduction to philosophy, is a main theme.

Place, time and participants

The dialogue takes place in the Lyceum - Gymnasium from, a spacious facility on the eastern outskirts of Athens . All interlocutors are historical people, but it must be reckoned that Plato gave them some fictional features.

The brothers Euthydemus and Dionysodorus came from Chios . From there they first emigrated to Thurioi , a Greek colony on the Gulf of Taranto . They later had to flee Thurioi. They then settled in the Athens area, where at the time of the fictional dialogue they had been living and teaching for many years. Ktesippus, who also takes part in the conversation in Plato's dialogue Lysis , was a young friend of Socrates; later he was present in prison when he died. Kleinias, the youngest participant in the dialogue, was a son of Axiochus, who was an uncle of the famous statesman Alkibiades .

The time of the dialogue action can only be inferred approximately; it lies in the period between about 420 and 404 BC. From individual information about historical persons, clues for the dating can be gained. Alkibiades, murdered in 404, is still alive, but the famous Sophist Protagoras mentioned in the dialogue , who was still active in 421, seems to have already died. Socrates, born in 469, as well as Euthydemus and Dionysodorus are already old, Ktesippus is a youth, Kleinias is still a youth.

content

Introductory framework

A framework introduces the dialogue. Socrates is asked by his friend and peer, Crito , who he talked to the day before at Lykeion. He reports that it was Euthydemos and Dionysodorus, two " all-fighters " who master both the physical and the spiritual art of fencing masterfully and give lessons in both. In the past, as Socrates tells us, they taught military skills and at the same time proved themselves as speechwriters and rhetoric teachers . Recently, despite their advanced age, they have still learned the art of debate and after one or two years of study they have started to teach in this field as well. Now they are considered unsurpassable masters of eristics . You can refute everything someone says, regardless of the actual truth, and you can teach this art to any student in a short time. Socrates tells Crito that, despite his age, he wants to take lessons from the two sophists, but is concerned that he might disgrace his teachers. The bombastic portrayal of the astonishing knowledge and abilities of the sophists shows that the praise is meant ironically and that Socrates considers the two to be charlatans in reality.

Socrates suggests that Crito also take part in the debate class. Crito agrees, but first wants to know what kind of wisdom the sophists are. Socrates then begins to reproduce the scenes from the previous day, which give an impression of the attitude and approach of the two teachers.

First Scene

In Lykeion, Socrates sees Euthydemus and Dionysodorus walking in a corridor with numerous students. Kleinias comes in and takes a seat next to Socrates. Since he is a strikingly attractive youngster, he attracts a lot of attention in the homoerotic milieu. He is followed by a crowd of his admirers, including Ktesippos. The two sophists, too, are clearly impressed by his sight and come over to them. Socrates greets them and ironically introduces them to Kleinias as wise men, exuberantly praising them as important teachers of the arts of war and judicial rhetoric. Euthydemos condescendingly states that he and his brother are only active on the side in these areas. They have now primarily turned to the task of teaching their students “excellence” ( aretḗ ) - that is, optimal ability - in general , and in this they are unsurpassed. Socrates remarks ironically that if that is true, they are like gods and, more than the Persian great king, favored by luck with all his might. The arrogant brothers do not notice the irony. They agree to deliver a sample of their art at once.

Socrates asks the sophists whether they are able not only to make their students excellent people, but also to make someone who is not yet convinced of their offer understand that excellence can be taught and that they themselves should do it be the best teachers. Dionysodorus affirms this. Then Socrates asks him to convince Kleinias; It is a heartfelt wish of everyone present that this boy develops optimally and does not fail.

Euthydemos begins with the trick question to Kleinias, whether learners are knowledgeable or ignorant. Dionysodorus whispers to Socrates that the boy will be refuted, however he answers. He thus shows that the refutation is an end in itself and does not serve to establish the truth. Kleinias decides on the answer that learners are knowledgeable and is immediately refuted by Euthydemos. Kleinias then adopts the opposite view, and now Dionysodorus shows him that he is wrong again. The sophists work with a trick: In their argumentation they take advantage of the fact that the Greek verb manthanein means both “to learn” and “to understand”. The helpless Kleinias gets confused by the failures. The admirers of the sophists laugh at him noisily at every defeat, which increases his embarrassment. This is followed by further refutations with fallacies in which Kleinias has to contribute with his answers and which he cannot counter.

Second scene

Socrates intervenes to bring relief to the badly pressed youth. He draws his attention to the fact that in order to be able to answer such questions, one must first become familiar with the use of the words. The present case concerns the ambiguity of the verb manthanein , which has been tacitly used in different senses. It describes both the intake of information by learners without prior knowledge and the understanding of a certain situation on the basis of already existing knowledge. Anyone who is not aware of the ambiguity can easily be confused with an argument that assumes uniqueness. However, as Socrates explains, this is just a game of words that does not yield anything. To really inspire wisdom and virtue, you have to put aside such jokes and deal seriously with the subject. This is what the philosopher calls upon the sophists to do. The following remarks have a protreptic character, they are intended to promote the Socratic-Platonic philosophy.

How a constructive joint effort for philosophical knowledge - as a contrast to eristics - can be designed is demonstrated by Socrates by asking Kleinia's helpful, further questions. It turns out that all people strive to be well. They achieve this goal when they are well stocked with goods. Different goods come into consideration: wealth, health, beauty, power and reputation, but also virtues such as prudence , justice and bravery as well as wisdom . That which appears to all people as the most important good is success (eutychía) . In any field, success can only be achieved for the competent, for those who have the necessary knowledge. Therefore man needs nothing more urgently than knowledge ( sophia : "knowledge", "insight", "wisdom"). Since the wise man understands the connections, he always acts correctly and is successful in everything. Resources such as wealth and power are of value only when they are used properly, and this requires wisdom; if you don't have them, your resources are actually damaging. Things are in themselves neither good nor bad, only wisdom makes them good and folly makes them evil. Therefore it is the task of every person to strive for wisdom in the first place. If he succeeds in this, he attains the associated pleasant state of mind, eudaimonia ("bliss").

Here the question arises whether a request for support in the search for wisdom makes sense. This is only the case when wisdom does not arise spontaneously, but can be learned with the help of an experienced person. To the delight of Socrates, Kleinias opts for the principle of teachability. In the current situation there is no need to examine the fundamental problem of communicability. At this point Socrates ends his train of thought. He asks the sophists to pick up the thread and now to explain what knowledge is important. You should clarify whether each knowledge contributes to the achievement of the goal, eudaimonia, or whether there is a certain individual knowledge that is the key to excellence.

Third scene

Dionysodorus and Euthydemus come back to the train. As in the first scene, they do not deal with the question in terms of content, but create confusion with arguments and fallacies ( sophisms ). Dionysodorus argues that if someone who is ignorant is made into a knower, he will become a different person. He would then no longer exist as who he was before. Whoever changes one person transforms him into another. In doing so, he brings about the downfall of whoever this person was before.

Ktesippos, who is in love with Kleinias, understands this as an insinuation that he wants to destroy the boy he loves, and energetically rejects this "lie". Euthydemos uses this as an opportunity to ask whether it is even possible to lie. He argues that anyone who says something is saying something about what is being said. The object of his statement is something definite, that is, a definite part of the things that are. The nonexistent is not, it cannot be anywhere, and no one can do anything with it. Nobody can create something that is nowhere. Beings, on the other hand, exist; their existence makes them true. Since every statement relates to a particular being and truth is based on being, every statement that is made is necessarily true because of its very existence. So there can be no lie. Ktesippos refuses to accept this argument. Then Dionysodorus concludes from the non-existence of untruth that there can be no contradiction either. Accordingly, Ktesippos did not contradict him at all. From his deliberations, the sophist not only concludes that one cannot say anything wrong, but even that one cannot even imagine something wrong. So there can be no error. Socrates, on the other hand, argues that this inference removes the distinction between knowledge and ignorance. The sophists' claim to impart knowledge thus becomes obsolete. Their reasoning is self-contradictory, because if you follow them, they themselves would be superfluous as teachers. In addition, if there are no false statements, it is also not possible to refute him - Socrates. Ktesippos accuses the eristicians of talking nonsense, but Socrates appeases him so as not to let a conflict arise.

Fourth scene

After the discussion has reached a dead end due to the fallacies, Socrates calls for seriousness. He turns back to Kleinias and returns to his question of what knowledge is necessary to attain wisdom. His train of thought is: Knowledge must have a use. Knowing how to make gold out of stones is useless if you don't know what to do with the gold produced. Even knowledge that provides immortality would be useless if one did not know how to use immortality. It is therefore necessary that the wise unite the knowledge of manufacture and knowledge of use. Wisdom must be something that whoever gains it inevitably knows how to use it properly. The wise man should not be like a craftsman who makes a musical instrument but cannot play the instrument himself. Kleinias, who agrees with Socrates, shows his understanding by giving additional examples of the separation of manufacturing and practical knowledge: Speechwriters cannot deliver their speeches; Generals win military victories, but then have to leave their fruits to the politicians.

Continuation of the framework story

Here the rendering of the dialogue action is suspended and the framework action is continued, because Crito interrupts the story of Socrates. He is impatient and finally wants to know what the search led to. Socrates confesses that the result is negative: the participants in the dialogue have only recognized that nothing known to them leads to wisdom and eudaimonia, not even the royal art of ruling. The question of what knowledge is wisdom has remained open after examining the various fields of knowledge. Socrates then turned again to the “omniscient” sophists, pleading with them to reveal the solution they claim to know. As was to be expected, Euthydemus dared to solve the problem. At this point Socrates resumes the verbatim rendering of the course of the conversation.

Fifth scene

In their already familiar way, the Eristicians propose a subtle fallacy. This boils down to the fact that everyone who knows something is a knower and as such knows everything, because since contrary statements exclude one another, one cannot be both knowing and ignorant at the same time. Accordingly, every person is omniscient from birth. The two sophists insist on this, but they cannot answer Ktesippo's specific question, how many teeth the other has. Instead, they present further absurd inferences that arise from their understanding of linguistic logic and that are compelling conclusions from their point of view. In the meantime, Ktesippus has grasped the principle of eristics well, and he succeeds in cornering the sophists with their own tricks. This fulfills the promise that one learns quickly from them. Finally, Dionysodorus plays a game with the possessive pronoun : "my" and "your" designate property, including living beings such as oxen and sheep that belong to someone. The owner can do what he wants with such creatures, he can give away, sell or slaughter the animals. Gods are also living beings. When Socrates speaks of "his" gods, he claims that he can give them away or sell them like farm animals. This causes great amusement in the audience.

In conclusion, Socrates ironically pays tribute to the sophists' achievement. Your statements are excellent, but only suitable for you and the small group of your students. Most people, and especially the serious ones, could not do anything with it. The eristic art of debate cannot be taught to them. After all, eristics has two advantages: it can be learned quickly, as Ktesippos has demonstrated, and it can not only be used against others, but also serves to refute the claims of their own authors.

Final framework story

After Crito has received such samples of eristics, he no longer shows any interest in learning them. He tells Socrates of his encounter with an unnamed court speech writer, who witnessed the appearance of the Eristiker in Lykeion. He criticized men who were now considered the wisest, but only chatted and dealt with worthless things. By this he meant the charlatans Euthydemus and Dionysodorus, but he directed his criticism expressly against philosophy in general and especially against Socrates. He wanted to discredit philosophy by lumping it together with the fallacy technique. His rebuke to Socrates was sharp; he said that the philosopher had behaved in bad taste when he entered such a debate. Anyone who deals with something like this is making himself look ridiculous.

Crito considers the criticism of philosophy to be wrong, but shares the view that Socrates should not have had such a public discussion. Socrates comments on the speechwriter's attack that he knows this type of opponent of philosophy. These are people who consider themselves the wisest, are addicted to glory and regard the philosophers as competitors. They stand between philosophy and politics and deal with both, but only insofar as it is necessary for their purposes and without taking any risks.

Crito is concerned about the future of his two young sons, especially the older one. Although he had created a beneficial home for them, he was unable to find a good teacher and educator who could lead them to philosophy. None of those who claim to be educators seem trustworthy. Socrates generalizes this: There are only a few real experts in any field. It is not about how competent or incompetent individual philosophers and educators are, but about the matter itself, about the value of philosophy. Crito should examine philosophy and form his own judgment. If it then seemed good to him, he should practice it himself, together with his children. Otherwise he should advise everyone against her.

Philosophical balance sheet

The question of the knowledge that constitutes wisdom and brings about eudaimonia remains unanswered in Euthydemos . The question of whether wisdom can be taught also remains open. Thus the dialogue ends aporetically , that is, in an apparently hopeless situation. It has only been possible to clarify the requirements that must be made of wisdom and to expose eristics as an unsuitable means of gaining knowledge.

It has been found that on the one hand eristics starts from principles of logic, on the other hand it cancels these with their fallacies. This makes the use of reason impossible and thus destroys the basis of the philosophical search for truth. All eristic fallacies are based on a lack of differentiation. Either no distinction is made between different meanings of a word or the limitation of the scope of a statement is disregarded. It is mistakenly assumed that one cannot say something about the same thing and deny it in other respects without violating the principle of contradiction . On this assumption, every non- tautological statement can be refuted. In some cases relative and absolute properties are confused or no distinction is made between predictive and identifying “is”. A confusion of predication and identity exists, for example, if from the statements “x is different from y” and “x is an F” it is concluded that y cannot be an F.

Time and background of writing

The Euthydemos is counted for language and substantive grounds to Plato's early works and later on within the group of early dialogues. What is striking is his proximity to the Menon dialogue , which has led to an intense debate about the chronological order of the two works. Today it is mostly assumed that Plato wrote the Euthydemus soon after his first trip to Sicily, but the time shortly before the trip is also considered. In any case, the drafting should fall in the first half of the 380s. The background is probably the foundation of Plato's philosophy school, the academy , around 387 BC. At that time it was one of his most pressing concerns to separate his concept of a philosophical training from competing ways of acquiring knowledge. He wanted to drastically illustrate the contrast between his dialectic and eristics.

Euthydemus and Dionysodorus show in Plato's account a number of characteristics of sophistic teachers. This includes, as foreigners, giving lessons in Athens against payment, teaching "excellence", emphasizing the extent of their knowledge and promising their students quick success. The speed of learning, which they emphasize as an advantage of their teaching, is for Plato a sign of a lack of seriousness; it contrasts with his concept of a long, thorough philosophical education. Their special emphasis on eristics also brings the brothers closer to the Megarics , a trend that rivaled the Platonists in the 4th century. It is therefore possible that Plato's caricaturing image of the two brothers should also serve as a polemic against the Megarics. The ontological argumentation of the Eristicians is influenced by the Eleatic philosophy, with which Plato dealt intensively.

An important key to understanding the background is the figure of the unnamed court speech writer, which is introduced at the end. The stranger attacks Socrates and philosophy violently and is in turn sharply criticized by Socrates. Here Plato evidently had a certain group of rhetoricians in mind who were opponents of his understanding of philosophy. Perhaps the anonymous critic can be understood as any typical representative of the opposing direction. But it is more likely that Plato had a certain person in mind. It is very likely that he was targeting his rival Isocrates , whose concept of upbringing and worldview were incompatible with Platonic teachings. The anonymous speechwriter appears in the Euthydemos in an unfavorable light: he listens to the whole debate and is then unable to recognize the blatant contrast between the Eristic and the Socratic approach, but instead presents a blanket condemnation of "philosophy" as a conclusion. Plato thus implicitly makes a devastating judgment about the ability of the opposing rhetorician to assess philosophical competence.

reception

Ancient and Middle Ages

In ancient times, interest in the Euthydemus was relatively modest, as the small number of scholias shows.

In his work " On the Sophistic Refutations ", Aristotle dealt with various fallacies that also occur in dialogue. It is not known whether he owed his knowledge of these sophisms to Euthydemos or some other source. In the 3rd century BC The Epicurean Kolotes von Lampsakos wrote the polemical text "Against Plato's Euthydemos ", which is only preserved in fragments.

In the tetralogical order of the works of Plato, which apparently in the 1st century BC Was introduced, the Euthydemos belongs to the sixth tetralogy. The historian of philosophy Diogenes Laertios counted him among the "refuting" writings and gave "The Eristiker" as an alternative title. In doing so, he referred to a now-lost script by the Middle Platonist Thrasyllos . The Middle Platonist Alcinous also classified Euthydemos among the refutation dialogues in his "textbook (didaskalikós) of the principles of Plato" ; he regarded it as a textbook for the dissolution of sophisms.

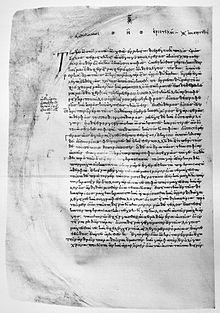

An antique papyrus fragment from the 2nd century contains a small piece of text; it is the only ancient text witness. The oldest surviving medieval manuscript was made at the end of the 9th century in the Byzantine Empire . In the Middle Ages the Euthydemos was unknown to the Latin- speaking scholarly world of the West; it was only rediscovered in the age of Renaissance humanism .

Early modern age

The humanist Marsilio Ficino translated the Euthydemos into Latin. He published the translation in Florence in 1484 in the complete edition of his Latin translations of Plato. Ficino was convinced that the aporia in the dialogue was only apparent and that Socrates had known how to overcome the perplexity. He said - anticipating a modern interpretation - that the apparent confusion of Socrates was part of a didactic strategy which took into account the limited capacity of the philosopher's interlocutors.

The first edition of the Greek text was published in Venice by Aldo Manuzio in September 1513 as part of the complete edition of Plato's works published by Markos Musuros .

Modern

In the 19th century, Plato's authorship was sometimes questioned or disputed, but in more recent research it is considered undoubtedly secured.

The absurdity of the caricaturing eristic argumentation has led some scholars to assess that this dialogue is a farce, a mere gimmick and a collection of sophistic subtleties. Paul Natorp , for example, refrained from “going into more detail about the polemics of this writing that emerged from a kind of carnival mood”. The comedy traits are often highlighted in the research literature. The editor Louis Méridier described the Euthydemos as a comedy in which the students of the sophists form the choir . However, this does not rule out a serious concern of the author. Some historians of philosophy also find important insights in Euthydemus ; they point out that behind the eristic gimmicks there is a serious philosophical problem, for example the question of the relationship between being and not being. The fact that the Euthydemos contains the oldest known protreptic text and is thus at the beginning of the history of this genre is appreciated. Franz von Kutschera sees in the protreptic parts "the advertisement for an important, new conception of philosophy, in which original, systematically very important thoughts are brought up".

The question of the extent to which Plato himself saw through and analyzed the logical consequences of the arguments that he put into the mouths of the dialogue characters is disputed. In any case, the Euthydemus is an important source for the history of pre-Aristotelian logic. It has been worked out on several occasions that the sophistics and eristics in the presentation of this dialogue are a caricaturing version of the Socratic-Platonic philosophy; for example, the eristic concept of omniscience caricatures Plato's anamnesis theory. Michael Erler's investigation has shown that the Euthydemos “ offers a negative reflection of what Plato considers right”.

Another controversial question in research is whether, for Plato's Socrates in Euthydemos, wisdom alone and directly brings about eudaimonia or is even identical to it, or whether external factors also make a - albeit relatively insignificant - contribution to well-being. Connected with this are the questions of what significance external, non-moral conditions can have in this teaching and whether Socrates succeeded in making plausible that eudaimonia depends solely on correct action, i.e. that coincidences do not play a role for it. It is certain that Plato regarded wisdom as a sufficient condition for eudaimonia, but the nature of the relationship between ethical knowledge and well-being remains to be clarified.

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff said that the Euthydemos used "not to be judged on merit"; the reason for this is that the opponents of Socrates "do not seem to deserve this effort of wit", and there is no positive return for Plato's philosophy. Here, however, “an art of construction and drama is called up which is equal to the works of the highest mastery”; “In the architectural structure, no dialogue in terms of cohesion and harmony can equal it”. Even Karl Praechter praised the "stimulus highest literary art that unfolds here" and "each time an in-depth reading and to auftuenden intricacies of individual representation". Paul Friedländer took a liking to the “rich counterpoint that characterizes this dialogue”. Olof Gigon pointed to the "unity and sovereign shaping"; the Euthydemus was "undoubtedly the masterpiece of Plato's early dialogues". Michael Erler also praised the artful structure.

Charles H. Kahn draws attention to the complexity of the work; it is intended and suitable for readers with different philosophical prior knowledge. It is a brilliant piece of comic literature. Even Thomas Alexander Szlezák sees in Euthydemos a masterpiece Platonic humor; One can only recognize this, however, if one knows the background and if one understands the larger context in which the dialogue fits within the Platonic philosophy. Thomas Chance considers the Euthydemos to be a perfect mix of serious and playful.

Editions and translations

- Otto Apelt (translator): Plato's dialogue Euthydemos . In: Otto Apelt (Ed.): Platon: Complete Dialogues , Vol. 3, Meiner, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-7873-1156-4 (translation with introduction and explanations; reprint of the 2nd, revised edition, Leipzig 1922)

- Gunther Eigler (Ed.): Platon: Works in Eight Volumes , Volume 2, 5th Edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-19095-5 , pp. 109-219 (reprint of the critical edition by Louis Méridier, 4th edition, Paris 1964, with the German translation by Friedrich Schleiermacher , 2nd, improved edition, Berlin 1818)

- Michael Erler (translator): Plato: Euthydemos (= Plato: Works , edited by Ernst Heitsch et al, Volume VI 1). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2017, ISBN 978-3-525-30413-6 (translation and commentary)

- Rudolf Rufener (translator): Plato: Frühdialoge (= anniversary edition of all works , vol. 1). Artemis, Zurich and Munich 1974, ISBN 3-7608-3640-2 , pp. 267–329 (with an introduction by Olof Gigon )

- Franz Susemihl (translator): Euthydemos . In: Erich Loewenthal (Ed.): Platon: All works in three volumes , Vol. 1, unchanged reprint of the 8th, revised edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-534-17918-8 , pp. 481-539 (only translation)

literature

Overview representations

- Louis-André Dorion: Euthydème . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 5, Part 1, CNRS Éditions, Paris 2012, ISBN 978-2-271-07335-8 , pp. 750-759

- Michael Erler : Platon ( Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity , edited by Hellmut Flashar , volume 2/2). Schwabe, Basel 2007, ISBN 978-3-7965-2237-6 , pp. 121-128, 591-594

Investigations and Comments

- Thomas H. Chance: Plato's Euthydemus. Analysis of What Is and Is Not Philosophy . University of California Press, Berkeley 1992, ISBN 0-520-07754-7 ( online )

- Michael Erler: Plato: Euthydemos. Translation and commentary (= Plato: Works , edited by Ernst Heitsch et al., Volume VI 1). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2017, ISBN 978-3-525-30413-6

- Ralph SW Hawtrey: Commentary on Plato's Euthydemus . American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia 1981, ISBN 0-87169-147-7

- Vittorio Hösle : Plato's 'Protreptikos'. Conversation events and subject of conversation in Plato's Euthydemos . In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 147, 2004, pp. 247–275

- Hermann Keulen: Investigations into Plato's "Euthydem" . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1971, ISBN 3-447-01239-0

- Lucia Palpacelli: L '"Eutidemo" di Platone. Una commedia straordinariamente seria. Vita e Pensiero, Milano 2009, ISBN 978-88-343-1828-7

- Thomas M. Robinson, Luc Brisson (eds.): Plato: Euthydemus, Lysis, Charmides. Proceedings of the V Symposium Platonicum. Selected papers . Academia Verlag, Sankt Augustin 2000, ISBN 3-89665-143-9

Web links

- Euthydemos , Greek text from the edition by John Burnet , 1903

- Euthydemos , German translation after Friedrich Schleiermacher

Remarks

- ↑ See to them Michel Narcy: Dionysodoros de Chios . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 2, Paris 1994, pp. 875–877; Michel Narcy: Euthydème de Chios . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 3, Paris 2000, pp. 390–392; Hermann Keulen: Studies on Plato's “Euthydem” , Wiesbaden 1971, pp. 7–9.

- ↑ See on Ktesippos Luc Brisson: Ctésippe de Péanée . In: Richard Goulet (Ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 2, Paris 1994, pp. 532 f.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemus 271b, 273a. See on Kleinias Luc Brisson: Clinias des Scambonides . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 2, Paris 1994, p. 442 f.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 121; William KC Guthrie : A History of Greek Philosophy , Vol. 4, Cambridge 1975, p. 267; Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, p. 318; Monique Canto : Plato: Euthydème , Paris 1989, p. 36 f.

- ↑ On Criton see Luc Brisson: Criton d'Alopékè . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 2, Paris 1994, pp. 522-526.

- ^ Plato, Euthydemos 271a – 272d.

- ↑ On this irony of Plato's Socrates see Louis-André Dorion: Euthydème . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 5, Part 1, Paris 2012, pp. 750–759, here: 753.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemus 272c-e.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemus 272e-274d.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemos 274d – 275c.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemos 275d-277c.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemus 277c-278d.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemus 279c. On this term, see Michael Erler (Commentator): Plato: Euthydemos (= Plato: Works. Translation and Commentary , Vol. VI 1), Göttingen 2017, p. 143.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemus 278d-282b. For eudaimonia in Euthydemus see Naomi Reshotko: Virtue as the Only Unconditional - But not Intrinsic - Good: Plato's Euthydemus 278e3-281e5 . In: Ancient Philosophy 21, 2001, pp. 325–334; Panos Dimas: Happiness in the Euthydemus . In: Phronesis 47, 2002, pp. 1-27.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemus 282b-e.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemos 283a – d.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemus 283E-288c.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemos 288c – 290d.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemos 290e – 293a.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemos 293b-303b.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemos 303c-304b.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemos 304c – 305a.

- ^ Plato, Euthydemos 305a – 306d.

- ↑ Plato, Euthydemos 306d – 307c.

- ↑ See Rainer Thiel : Aporie and Knowledge. Strategies of argumentative progress in Plato's dialogues using the example of 'Euthydemos' . In: Bodo Guthmüller, Wolfgang G. Müller (eds.): Dialogue and culture of conversation in the Renaissance , Wiesbaden 2004, pp. 33–45, here: 37–42. Franz von Kutschera offers a clear list and discussion of the fallacies: Platon's Philosophy , Vol. 1, Paderborn 2002, pp. 197–202.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, pp. 121 f., 124 f .; William KC Guthrie: A History of Greek Philosophy , Vol. 4, Cambridge 1975, pp. 275 f .; Thomas H. Chance: Plato's Euthydemus. Analysis of What Is and Is Not Philosophy , Berkeley 1992, pp. 3-6, 18-21; Ralph SW Hawtrey: Commentary on Plato's Euthydemus , Philadelphia 1981, pp. 3-10; Monique Canto: Plato: Euthydème , Paris 1989, pp. 37-40; Lucia Palpacelli: L '"Eutidemo" di Platone , Milano 2009, pp. 33-41. André Jean Festugière advocates dating around 390, before the trip to Sicily and the founding of the Academy : Les trois “protreptiques” de Platon , Paris 1973, pp. 159–170.

- ^ Louis-André Dorion: Euthydème . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 5, Part 1, Paris 2012, pp. 750–759, here: 751–753; Louis-André Dorion: Euthydème et Dionysodore sont-ils des Mégariques? In: Thomas M. Robinson, Luc Brisson (eds.): Plato: Euthydemus, Lysis, Charmides , Sankt Augustin 2000, pp. 35–50; Louis Méridier (ed.): Plato: Œuvres complètes , vol. 5, part 1, 3rd edition, Paris 1956, pp. 128–130; Ralph SW Hawtrey: Commentary on Plato's Euthydemus , Philadelphia 1981, pp. 23-30; Lucia Palpacelli: L '"Eutidemo" di Platone , Milano 2009, pp. 51-56.

- ↑ Ernst Heitsch : The anonymous in the "Euthydem" . In: Hermes 128, 2000, pp. 392-404; Vittorio Hösle: Plato's 'Protreptikos' . In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 147, 2004, pp. 247–275, here: 261 f. On the question of identification, see Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 123; William KC Guthrie: A History of Greek Philosophy , Vol. 4, Cambridge 1975, pp. 282 f .; Louis Méridier (ed.): Plato: Œuvres complètes , vol. 5, part 1, 3rd edition, Paris 1956, pp. 133-138; Monique Canto: Plato: Euthydème , Paris 1989, pp. 33-36; Christoph Eucken : Isokrates , Berlin 1983, pp. 47-53; Lucia Palpacelli: L'Eutidemo di Platone , Milano 2009, pp. 220-226.

- ^ Hermann Keulen: Investigations on Plato's "Euthydem" , Wiesbaden 1971, p. 1 note 1.

- ↑ See Louis-André Dorion: Une prétendue dette d'Aristote à l'endroit de Plato . In: Les Études Classiques 61, 1993, pp. 97-113.

- ↑ See the work of Kolotes Michael Erler: The Epicurus School . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , vol. 4/1, Basel 1994, p. 237 f.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 3: 57-59.

- ↑ Alkinous, Didaskalikos 6.

- ↑ Corpus dei Papiri Filosofici Greci e Latini (CPF) , Part 1, Vol. 1 ***, Firenze 1999, p. 62 f.

- ↑ Oxford, Bodleian Library , Clarke 39 (= "Codex B" of the Plato textual tradition).

- ↑ For Ficino's interpretation of Euthydemos see Michael Erler: The Sokratesbild in Ficino's argumenta for the smaller Platonic dialogues . In: Ada Neschke-Hentschke (Ed.): Argumenta in dialogos Platonis , Part 1, Basel 2010, pp. 247–265, here: 249–255.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 121.

- ^ Paul Natorp: Plato's theory of ideas , 3rd edition, Darmstadt 1961 (reprint of the 2nd edition from 1922), p. 122.

- ↑ Louis Méridier (Ed.): Plato: Œuvres complètes , vol. 5, part 1, 3rd edition, Paris 1956, p. 119 f. Cf. Monique Canto: L'intrigue philosophique. Essai sur l'Euthydème de Platon , Paris 1987, pp. 95-97; Lucia Palpacelli: L'Eutidemo di Platone , Milano 2009, pp. 242–246.

- ↑ Michael Erler: The sense of the aporias in the dialogues of Plato , Berlin 1987, pp. 213-256.

- ↑ Thomas H. Chance: Plato's Euthydemus. Analysis of What Is and Is Not Philosophy , Berkeley 1992, p. 14; Hermann Keulen: Investigations on Plato's "Euthydem" , Wiesbaden 1971, p. 4 f., 40, 76; Vittorio Hösle: Plato's 'Protreptikos' . In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 147, 2004, pp. 247–275, here: 247–250.

- ^ Franz von Kutschera: Plato's Philosophy , Vol. 1, Paderborn 2002, pp. 209 f.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 124 f. See Myles F. Burnyeat: Plato on how not to speak of what is not: Euthydemus 283a-288a . In: Monique Canto-Sperber, Pierre Pellegrin (eds.): Le style de la pensée , Paris 2002, pp. 40-66.

- ↑ Walter Mesch: The sophistic handling of time in Plato's Euthydemos . In: Thomas M. Robinson, Luc Brisson (eds.): Plato: Euthydemus, Lysis, Charmides , Sankt Augustin 2000, pp. 51–58, here: p. 51 and note 1. Cf. Hermann Keulen: Investigations on Platons “Euthydem” , Wiesbaden 1971, p. 58 f .; Ralph SW Hawtrey: Commentary on Plato's Euthydemus , Philadelphia 1981, pp. 21 f .; Thomas Alexander Szlezák: Plato and the writing of philosophy , Berlin 1985, pp. 50–65.

- ↑ Michael Erler: The sense of aporias in Plato's dialogues , Berlin 1987, p. 254. Cf. similar observations in Lucia Palpacelli: L '"Eutidemo" di Platone , Milano 2009, pp. 308-313 and Vittorio Hösle: Platons' Protreptikos' . In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 147, 2004, pp. 247–275, here: 264.

- ↑ See the overview in Marcel van Ackeren : Das Wissen vom Guten , Amsterdam 2003, pp. 41–52. See Daniel C. Russell: Plato on Pleasure and the Good Life , Oxford 2005, pp. 16-47; Ursula Wolf : The search for the good life. Platons Frühdialoge , Reinbek 1996, pp. 67–77.

- ^ Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff: Platon. His life and his works , 5th edition, Berlin 1959 (1st edition Berlin 1919), pp. 231, 239.

- ^ Karl Praechter: Plato and Euthydemos . In: Philologus 87, 1932, pp. 121–135, here: 121, 135.

- ^ Paul Friedländer: Platon , Vol. 2, 3rd, improved edition, Berlin 1964, p. 166 f.

- ↑ Olof Gigon: Introduction . In: Platon: Frühdialoge (= anniversary edition of all works , vol. 1), Zurich / Munich 1974, p. V – CV, here: LXXXVII.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 123.

- ^ Charles H. Kahn: Plato and the Socratic Dialogue , Cambridge 1996, pp. 321-325.

- ↑ Thomas Alexander Szlezák: Plato and the writing of philosophy , Berlin 1985, p. 49. Cf. Thomas Alexander Szlezák: Sokrates' Spott über Secrecy . In: Antike und Abendland 26, 1980, pp. 75–89.

- ↑ Thomas H. Chance: Plato's Euthydemus. Analysis of What Is and Is Not Philosophy , Berkeley 1992, p. 15.