Fernidol

In 1976 , the literary scholar Elisabeth Frenzel called Fernidol a literary figure who is loved by another figure, although the two have never met each other, or at most very briefly.

According to Frenzel, the Fernidol is much more than just a person in whom the loving figure finds romantic or sexual interest. Rather, it is the representation of an ideal . The Fernidol kindles love, wants to be sought and can be found because - as an idol - it forms an essentially personal conception of this ideal.

Long-distance love is always triggered by one of the following events:

- the (then loving) figure receives an oral report on the distant figure and its advantages

- the figure looks at the Fernidol in a dream

- the figure sees a picture on which the Fernidol is represented

- the figure sees another sign that announces the Fernidol (in Tristan and Isolde e.g. a swallow)

The figure then either falls under a love spell or realizes that it is fatefully linked to the distant figure. The former is more the case in the western fairy tale tradition, the latter more in the eastern (Indian, Persian, Arabic) storytelling tradition. In both cases, the loving figure then moves out to win the Fernidol (in Frenzel's jargon: "to bring home").

Greek antiquity

Occasionally, the motif of the Fernidol brought home appears in ancient Greek literature . Frenzel cites a fairy tale handed down by Strabo († after 23 AD) as an example , in which an eagle throws a shoe stolen from the Hetaera Rhotopis into King Psammetich's lap; the king is enchanted by this sign and goes in search of the owner.

Indian, Persian and Arabic literature

Since the literary motif of the Fernidol brought home plays a major role early on in Indian , Persian and Arabic literature ( Divyavadana , Nala and Damayanti , Bakhtyar Nameh , Firdausi : Shāhnāme , Somadeva: Kathasaritsagara , Djami: Yusuf o Zuleicha , Arabian Nights ), Frenzel suspected a connection to the exogamy law , which was traditionally handled very strictly, especially in India. Characteristic of the oriental narrative was the fame that preceded the respective dream princess because of her strength and beauty and which triggered a fateful inclination in her admirer long before the two first faced each other.

- Dream images

In the most famous Indian epic, the Mahabharata (first written down between 400 BC and 400 AD), Aniruddha and Usa fall in love in a dream. This variant of the Fernidol motif appears again and again in world literature from then on. Frenzel has argued that the dream is always meaningfully fulfilled in poetry, in the sense that a dream image sent by God links a magical image between the dreaming and the depicted. In Subandhu's novel Vasavadatta (2nd half of the 7th century) and Bhasa's play Svapnavasavadattam (around 600), both of which tell the story of Prince Kandarpaketu, his lover appears in a dream. In Firdausi's Book of Kings (1010) it is a king's daughter who at the end finds her dream prince. The Inclusa story of the novel collection Seven Wise Masters , in which the couple who find each other are connected by a double dream , probably goes back to Persian origin.

- Physical images

Just like a dream, a picture can bewitch in poetry . In this context, Frenzel refers to the popular belief that the acquisition of a portrait is followed by violence over the person depicted. Relevant stories in which someone is struck by the sight of a picture of love can be found in about the Arabian Nights ( Story of Prince Sayf al-Muluk , 759-776; Ibrahim and Jamila , 953-959). Already in the Jataka collections (since the 3rd century BC) about the life of the Buddha , the Bodhisattva asked his parents, who urged him to marry, to realize his dream idol and created a physical image of his dream image for this purpose. In Nachshabi's Parrot Book (1330), the Persian redesign of an Indian narrative, the emperor of China saw a dream image that was painted by the vizier according to his description and hung up like an advertisement. In a story from the collection of novels, Seven Wise Masters , the rich Philo has a sculpture made; a traveler thinks he recognizes his wife in this, which in the end enables Philo to steal the wife. Other works in which distant idols are discovered through images are Kalidasa : Malavikagnimitra (drama), Dandin: The deeds of the ten princes (novel) and Nezāmi : Seven beauties (epic).

Germanic and north-western European legends

In the West too, stories about dangerous bridal journeys ( Nibelungen saga ) emerged early on . It is true that royal daughters like Brunhild and Kriemhild also had a reputation in this; However, it was neither magic nor a love determined in advance by fate that incited Gunther or Siegfried to go on their bridal trips, but a desire for conquest.

The Tristan-und-Isolde material, on the other hand, which is not of Germanic but of Welsh-Scottish-British origin, was part of the tradition of fairy tales that began with the Greeks; In the early versions ( Estoire , 12th century; Eilhart von Oberg , around 1180) a swallow brings a hair of Isolde to König Marke as a personal seal, whereupon he sends Tristan as a suitor. The only surviving Middle English version, Sir Tristrem (around 1300), is already clearly influenced by Asian models in its Fernidol motif.

In the old Icelandic saga , too , the motif of the Fernidol brought home was treated in a fairytale way, for example in the Kormáks saga (1st half of the 13th century) about a skald who falls into unhappy love for Steingerdr after her lovely feet (but not the woman) sees. Another example is the Kudrun saga (around 1240), in which the king's daughter Hilde lets herself be won over to the distant King Hettel after Horand's beguiling song enchants her. In the Göngu Hrólfs saga (13th / 14th century) Jarl Eirik receives the magical sign at the grave of his wife. In the Rémundar saga keisarasonar (14th century) and the Þjalar-Jóns saga (14th century), it is the sight of an image that enchants lovers.

Provencal trobadord poetry

The motif of the fateful obsession with love, sparked by Fernidol , only reached Europe via Arab Spain and with the Crusades . There it manifested itself since the 11th century in the Provencal trobadord poetry , where wish refusal was transformed into Minneglück . The Minne literature used a spiritualisiertes ideal of love, taught the service and patience. Trobadors like Jaufré Rudel (1100– around 1147), Guilhen de Cabestaing (1162–1212) and Uc de Saint Circ (1217–1253) celebrated long-distance love ( amor de lonh ).

Renaissance

The Renaissance humanism brought - with his delight in the wealth of resources from which to draw was - from the 14th century to a further boost reception of eastern literature. Thus around 1470/1480 Antonius von Pforr translated the Panchatantra into German. In the wake of the reception of Eastern literature, many new chivalric novels were created ; the motif of the Fernidol brought home was often central: Partonopeus de Blois , Hue de Rotelandes Ipomedon , Amadis , Nicholas Trivets Annales , Antonio Pucci's Historia della reina d'oriente , Geoffrey Chaucer's The Man of Law's Tale , The Beautiful Magelone , Elisabeth von Lorraine's Herpin and Palmerín de Oliva . In Giovanni Boccaccio's Decamerone (1349–1353), Prince Gerbino and the Princess of Tunis fall in love without ever having seen the other.

In the Renaissance literature, too, the Fernidol motif by no means only appeared in the context of chivalric novels. One example is Giovanni Fiorentino's collection of novellas Pecorone (1378/1390), in which a young Florentine nobleman, in intense love for a nun he has never seen face to face, is on fire and becomes a monk himself in order to be able to approach the beloved as a chaplain; the fulfillment of love then consists in daily mutual storytelling.

In Edmund Spenser's epic poem The Faerie Queene (1590–1596), King Arthur passionately loves the distant fairy queen Gloriana, and the knight Marinell loves the knight Britomart.

Baroque

In the baroque literature , the motif of the Fernidol brought home, as Frenzel described, "should once again prove its structure-forming power and force an abundance of orientalizing affairs under the tension between flaming love, burning longing and glowing union" .

Golden Age of Spain

It was no coincidence that Miguel de Cervantes ' novel Don Quixote , a satirical attack on chivalric novels, also targeted the narrative of the Fernidol in 1606/1615; with Cervantes this idol ( dulcinea ) only exists in the knight's imagination. A few decades after Cervantes' death, Antonio Coello revised his novella The Jealous Estremadurer and published it under the title El celoso extremeño ; the hero of the title loses his niece, who was jealously guarded in Madrid, because a young man from Seville sees her picture and cannot forget the beautiful again.

The playwrights of the Siglo de Oro were mainly inspired by works such as the Estoria de España , Amadis and Palmerín . Lope de Vega used the motif three times ( El mas galan portugues Duque de Vergança , 1617; La prision sin culpa , 1617; Los pacalios de Galiana , 1638). Authors such as Antonio Mira de Amescua ( El galán, valiente y discreto , before 1644), Antonio Martínez de Meneses ( Amar sin ver , 1663), Agustín Moreto ( Yo por vos y vos por otro , before 1669; Lo que puede la aprensión , 1669) and Álvaro Cubillo de Aragón ( Añasco el de Talavera , around 1670) drove the motif of the Fernidols brought home at the same time to admit the unbelievability of distant love and to grotesquely exaggeration.

France

In France, from 1632 to 1637, Marin le Roy de Gomberville wrote the novel Polexandre about a prince whom the search for his Fernidol Alcidiana leads to Mexico and the Antilles. In 1651 he had La jeune Aldiciane succeed . Influenced by Polexandre was Madeleine de Scudéry's novel Ibrahim ou l'illustre Bassa (1641), a work that inspired La Calprenède to his novel Cléopâtre (1647-1658). In Charles Sorel's anti-sentimental and anti-courteous novel Histoire comique de Francion (1623), Francion's chain of amorous adventures ends with the fact that he is united with his Fernidol.

German-speaking area

In German-speaking countries, Philipp von Zesen processed Mlle de Scudery's novel into his own novel: Ibrahims or Des Durchleuchtigen Bassa and the constant Isabellen miracle story (1645). Daniel Casper von Lohenstein's variant of the motif of the fetched Fernidol took up again and used it for a tragedy by Ibrahim (1653), while Andreas Heinrich Bucholtz edited it for a subplot of his novel Hercules and Valiska (1659–1660). Anton Ulrich von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel used the motif variant several times in his state novels ( The Serene Syrian Aramena , from 1669; Roman Octavia , from 1677). The last author of heroic-gallant novels, Heinrich Anselm von Ziegler and Kliphausen , also made the prince dream of a Fernidol in his novel Die Asiatische Banise (1689).

18th century

Carlo Gozzi's tragic comedy Turandot (1762) was inspired by a Persian tale that also reached Europe via the fairy tale collection A Thousand and One Days ; Prince Kalaf falls for the imperial daughter after seeing her portrait. Friedrich Schiller reworked the subject in 1801, and the version that is still best known today is Giacomo Puccini's opera of the same name, which premiered in 1926 .

In 1764, Christoph Martin Wieland published his Don Quixote- influenced novel The Victory of Nature Over Enthusiasm or the Adventures of Don Silvio von Rosalva , in which the eponymous hero finds a miniature picture that refers the obsessive reader of fashionable fairy tales to a princess who is supposed to be in the form of a butterfly must be converted back; the search for beauty not only brings him to his senses, but also to a beautiful reality. Wieland used the motif again in his romantic poem Oberon (1780), also in an ironic way: in it, the fairy king sends dreams to both the knight Hüon and the Baghdad princess Rezia, which make them love each other. Wieland's works had a great influence on the romantic poets as well as on opera history ( Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart : Die Zauberflöte , 1791: aria “This portrait is enchantingly beautiful” ; Carl Maria von Weber : Oberon , 1826).

Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz had already written his posthumously printed fragment Der Waldbruder in 1776 , whose dreamy and manipulation-prone title figure in Fernliebe u. a. to the Countess Stella; in the end the forest brother fails because of reality.

Classic and Romantic

In Friedrich Schiller's work , the motif appears in Maria Stuart (1800) as well as in Turandot : Mortimer grasps his inclination towards the heroine the moment he sees her image.

In Ludwig Teck's novel Franz Sternbald's Wanderings (1798), the Fernidol motif, which Wieland had last used playfully and ironically, appears once again in all seriousness. The eponymous hero chases after his dream love, Marie, and thus contradicts - with reference to Jaufré Rudel - the reason that the romantics repeatedly reviled. Another typical example of the treatment of the Fernidol motif in Romanticism is Clemens Brentano's comedy Ponce de Leon , in which Ponce loves Isidora, of whom he has only seen one picture. The motif here resolutely detaches from its old magical foundation and is romantically redefined as the "epitome of aimless love that lives only from longing" . This spiritualized love lives from the fact that the love object is not seen . Frenzel describes how Fernidolmotiv “paired thinking and looking, called up dark forces, paid tribute to clairvoyance, hunch, sleepwalking” and thus enabled the poets to “participate in the science of the unconscious” in the same way as Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert himself presented this in his views from the night side of natural science (1808).

On the basis of Schubert's considerations Heinrich von Kleist was then able to write Das Käthchen von Heilbronn (1808), the subject of which was a folk tale that originated at the fair, but which Kleist was then able to give a dream motif that was decidedly romantic Tradition. ETA Hoffmann was also obliged to Schubert , who used the motif of the Fernidol brought home several times, first in Die Automate (1814). In Hoffmann's stories The Artushof and The Jesuit Church in G. (both 1816) the main character - in both cases a painter - recognizes that the realization of long-distance love can only be bought with artistic inability. In Meister Martin der Küfner und seine Gesellen (1819) the artist longs for a picture of the Madonna and not for the cooper's daughter Rosa, who seems to embody it. Similarly, the wooing of the monk Medardus in The Elixirs of the Devil (1815-1816) misses the point. Another story by Hoffmann, in which the encounter with the archetype does not bring fulfillment but rather renunciation, is finally The Duplicate .

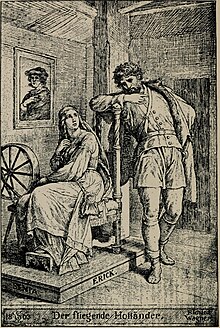

In Wilhelm Hauff's story Die Bettlerin vom Pont des Arts (1827) the motif experiences a variation in that a female portrait in two men does not evoke new but memories of lost love that needs to be reawakened. Richard Wagner's opera The Flying Dutchman (1843) can also be assigned to Romanticism ; Senta is enchanted by the painting of a "pale man with a dark beard and in black clothes".

Some of the fairy tales collected by the Brothers Grimm have drawn from the stock of motifs in Indian literature, above all The Faithful John (1819), in which the loyal servant cannot prevent his young king from seeing the picture of a king's daughter, which he must then have want.

Younger literature, film

Paul Verlaine , a representative of French symbolism , wrote his poem Mon Rêve Familier in 1866 , in which disillusionment replaces homecoming.

In contrast, E. Marlitt used a very conventional approach in her novel Im Schillingshof (1879), in which Arnold von Schilling falls in love with the distant Mercedes when he comes across her portrait. In 1917 Hedwig Courths-Mahler published her novel Griseldis , the title character of which falls in love with Count Harro when she first sees his photo.

In modern times, new media appear to awaken distant love: in Leonard Bernstein's musical On the Town (1944), for example, an advertising poster, in Erich Loest's story Etappe Rom (1975) knocking on a prison wall and in Richard Matheson's novel Bid Time Return (1975; better known is the film adaptation, A Deadly Dream ) an old photograph. In Dieter Wellershoff's novel Die Sirene (1980) and Robert van Ackeren's feature film Die Venusfalle (1988) it is a voice on the phone that arouses passionate love in the male main character. As early as 1977, Canadian Elizabeth Hay told the story of a man who fell in love with a voice on the radio in Late Nights on Air . An even more current variation of the Fernidol motif was offered in 2013 by Spike Jonzes' film Her , in which the main male character falls in love with the voice of his new operating system .

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 149 .

- ↑ a b c d Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 153 .

- ↑ a b c d Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 150 .

- ↑ a b c d Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 154 .

- ^ Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 154 f .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 155 .

- ^ Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 153 f .

- ^ Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 151 .

- ^ Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 151 f .

- ^ Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 152 .

- ^ Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 150, 152 .

- ↑ a b c d e Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 156 .

- ^ Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 155 f .

- ↑ a b c d Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 157 .

- ^ Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 156 f .

- ↑ a b c Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 158 .

- ^ Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 157 f .

- ^ Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 158 f .

- ↑ a b Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 159 .

- ↑ a b Elisabeth Frenzel: Motives of world literature. A lexicon of poetry-historical longitudinal sections . 5th edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-520-30105-9 , pp. 159 f .