Franz Oppenhoff

Franz Oppenhoff (born August 18, 1902 in Aachen ; † March 25, 1945 there ) was a German lawyer and Lord Mayor of Aachen between 1944 and 1945 . He was the nephew of Joseph Oppenhoff .

Life

Career

Franz Oppenhoff was the son of the school board member Franz Oppenhoff (1860-1920) and grandson of the district court president Theodor Oppenhoff . After graduating from high school in 1921, Franz Oppenhoff initially did a commercial apprenticeship and worked as an employee in the export department of a company until 1924, as there was initially no money to study. He then studied law at the University of Cologne , where he became an active member of the Rheinpfalz Catholic Student Association in the Cartel Association of Catholic German Student Associations . In 1933 he founded a law firm in Aachen. Oppenhoff was a staunch Catholic and deeply involved in church life.

time of the nationalsocialism

Oppenhoff had always refused to join the NSDAP and in his personal file his “National Socialist reliability was questioned”, according to the legal historian Hans-Werner Fröhlich. Oppenhoff was committed to defending priests and religious. In 1937 he also took over the legal representation of the Wilhelm Metz printing works, in which the church newspaper for the diocese of Aachen was printed and whose owner was a Jew . Oppenhoff campaigned against the expropriation of the company after the papal encyclical Mit Brennender Sorge , which was suppressed by the Nazi regime, was printed there. Because of his fearless behavior, Oppenhoff was warned several times by the Nazis and his office was searched until it was forcibly closed.

From April 1942 Oppenhoff worked for the Aachen armaments company Veltrup as a lawyer and deputy managing director and escaped being drafted into the Wehrmacht through this service obligation .

Exemption and appointment as mayor

In September 1944, American troops were close to Aachen. Oppenhoff crossed the border into Belgium and made contact with the Americans. Aachen was evacuated on the orders of the Nazi authorities, but around 6,000 residents were able to hide in the city. In October, through the mediation of the Catholic bishop of Aachen, Johannes Joseph van der Velden , Oppenhoff got in touch with the American major who was to take over the military government in Aachen. After the city was taken by the Americans, the military government appointed Oppenhoff, who was considered a politically unaffected lawyer, to be mayor on October 31, 1944. As a condition for this, Oppenhoff had obtained an assurance beforehand that he would not have to do anything that would harm his fellow citizens, the German people and the soldiers. In an appeal, he called on the residents to help build a "new, true and just fatherland for all".

"Aachen Scandal"

At the end of 1944, the American secret service officer Saul K. Padover came to Aachen. He conducted interviews with Oppenhoff, van der Velden and many other Aacheners, which he published in 1946. In January 1945, Padover and two employees submitted a detailed report on the civil administration of Aachen organized by Oppenhoff. This shows that Oppenhoff had a strictly Catholic- conservative , strictly anti-communist and undemocratic political attitude. He also filled all leading positions in the administration with supporters of his ideology, including the textile merchant Kurt Pfeiffer , the art historian Peter Mennicken and the textile industrialist Josef Hirtz . According to Padover's assessment, Oppenhoff pursued a plan to establish an authoritarian post-war order based on the model of the dictatorships of Mussolini or Franco . According to Padover, he refused to involve social democrats, communists or trade unionists in civil administration.

The incident, known as the “Aachen Scandal”, falls into a phase of clarification in American occupation policy that lasted until the summer of 1945, in which several concepts based on different ideological assumptions and experiences for dealing with the population in those liberated from Nazi rule Areas of Germany competed with each other. Padover represented a notion that was widespread in leading American government circles at the beginning of the occupation, which was based on a basic German mood that was largely firmly anchored in National Socialism and resisted the occupiers. In order to counter it, this current wanted to entrust mainly left-wing forces with leadership positions in Germany, since they alone had to muster a reservoir of staunch Nazi opponents. Padover was accordingly alarmed by the fact that Oppenhoff's conservative government on the one hand sabotaged the participation of left-wing representatives, on the other hand it tolerated former NSDAP members in its ranks, who were largely insignificant followers. A distinction between "fellow travelers" and "burdened", which later became the standard of American action, was still alien to the occupation policy actors of the US Army at that time. The dismissal of 27 employees of the new city administration named in the Aachener Nachrichten at the beginning of February 1945 was probably due directly to Padovers reports. Two camps were then formed within the occupation army in Aachen, one of which advocated the personnel purge and advocated a much greater distance between the American occupation forces and the local German population, while the other defended Oppenhoff and wanted to continue the more pragmatic course initially pursued.

In government circles, Padovers reporting met with great acceptance and was considered credible. Oppenhoff's release was practically imminent in the spring and only became obsolete after his murder. However, this turn of events did not support Padover's fears that the German city leadership was too close to the Nazis; on the contrary, it proved that the National Socialists viewed Oppenhoff as a traitor. The choice of Oppenhoff's successor Wilhelm Rombach , who also came from the bourgeois Catholic camp and had no left-wing past, also did not correspond to Padover's ideas. It was not until May 1945, when the Cold War broke out, that the mediating line propagated by Robert Murphy prevailed, which neither intended to massively support the German left nor to practice complete non-interference in the spirit of Henry Morgenthaus . Rather, a broad spectrum of representatives from the “center” were used to build a non-Nazi West Germany and they wanted to deny access to political decision-making offices for “both the extreme right and the extreme left”. Murphy himself had already visited Aachen shortly after Oppenhoff's appointment and praised his courage at the time.

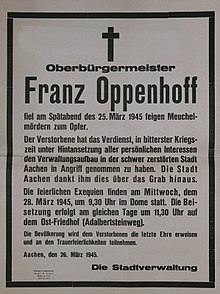

assassination

Oppenhoff was aware that the National Socialists were trying to kill him. In an interview, he said, “They swore they would kill me and I fear they will too. I will fare like Rathenau and others. Maybe the skydiver is meant for me. "

On March 25, 1945 ( Palm Sunday ) Oppenhoff was murdered in front of his house. It was immediately assumed that the act had been committed by a command of the National Socialist werewolf . According to current knowledge, these were not local Nazis or irregulars, but a made up of members of the SS and Luftwaffe compiled commando operation that the murder on the direct orders of Heinrich Himmler committed suicide. They had got behind the front line in a captured American plane and jumped off with parachutes.

Oppenhoff was buried in the family crypt on the Aachen Ostfriedhof . The later senior city director of Aachen, Anton short , was instrumental in ensuring that Oppenhoff's widow received a pension as if he had properly completed his career.

Persecution of the perpetrators

The command, which also included a 16-year-old HJ member and the 23-year-old BDM main group leader Ilse Hirsch, tried to flee across the Rhine back to the unoccupied area after the mission had been carried out. The alleged murderer of Oppenhoff, the Austrian Sepp Leitgeb, died in a mine in the Eifel ; Ilse Hirsch was seriously injured. All other members - with the exception of the leader - were tracked down by the British secret service SIS and brought before the Aachen Regional Court in 1949 . Jail terms of one and four years were imposed, Ilse Hirsch was acquitted, the Hitler Youth was not charged at all. In two follow-up proceedings, the prison sentences were further reduced by the same court and finally, in accordance with the Impunity Act of 1954, “because of a lack of orders”.

The Aachen lawyer Hans-Werner Fröhlich found out in 2013 that the presiding judge of the Aachen Chamber had been a member of the NSDAP since 1937 and a member of a special court set up by the National Socialists; an assessor at the jury had also been a member of the NSDAP.

Honors

- After Franz Oppenhoff, the Kaiser Allee in Aachen was renamed Oppenhoffallee. The city of Aachen erected a memorial to him at the beginning of the avenue at the level of Schlossstrasse. In addition, as part of the Ways Against Forgetting project, a memorial stone was embedded in the ground with the following inscription:

“After American troops liberated Aachen from the Nazis, Franz Oppenhoff was appointed Lord Mayor of his hometown on October 31, 1944. That is why the Nazi leadership in Berlin sent a werewolf command to Aachen, which Franz Oppenhoff shot in front of his house on March 25, 1945 "

- In 1985, Hannes Heer made a documentary about Oppenhoff's murder.

- In 1999 the Catholic Church accepted Franz Oppenhoff as a witness of faith in the German martyrology of the 20th century .

See also

literature

Documents

- LG Aachen, October 22, 1949 - Himmler ordered the mayor of Aachen appointed by the Americans to be shot by a 'werewolf command'. In: Justice and Nazi crimes . Collection of German convictions for Nazi homicidal crimes 1945–1966. Volume V, edited by Adelheid L. Rüter-Ehlermann and Christiaan F. Rüter , Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam 1970, No. 173, pp. 417-447 ( digitized version ).

Lexicons and short biographies

- Bernhard Poll : Franz Oppenhoff. In: Edmund Strutz (Ed.) Rheinische Lebensbilder. Volume 1, Cologne 1983, ISBN 3-7927-0717-9 .

- Robert Jauch: Franz Oppenhoff. In: Siegfried Koß, Wolfgang Löhr (Hrsg.): Biographisches Lexikon des KV. 2nd part (= Revocatio historiae. Volume 3). SH-Verlag, Schernfeld 1993, ISBN 3-923621-98-1 , p. 101 ff.

- Klaus Schwabe : Franz Oppenhoff. In: Bert Kasties, Manfred Sicking (Ed.): Aacheners make history. Portraits of historical figures. Volume 1, Shaker Verlag, Aachen 1997, ISBN 978-3-8265-3003-6 , pp. 171-184.

- August Brecher (1920–2001): Franz Oppenhoff. In: Helmut Moll (ed. On behalf of the German Bishops' Conference): Witnesses for Christ. The German martyrology of the 20th century. Volume 1, Schöningh, Paderborn 1999 (last unchanged in: 7th, revised and updated edition 2019, volume 1, ISBN 978-3-506-78012-6 , pp. 63-65).

Research literature

- Volker Koop : Himmler's last line-up. The Nazi organization "Werewolf". Böhlau, Cologne et al. 2008, ISBN 978-3-412-20191-3 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- Klaus Schwabe: Aachen at the end of the Second World War: Prelude to the post-war period? In: Kurt Düwell , Michael Matheus (eds.): End of the war and a new beginning. West Germany and Luxembourg between 1944 and 1947 (= historical regional studies. 46). Published by the Institute for Historical Regional Studies at the University of Mainz . Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 978-3-515-06974-8 (published online at regionalgeschichte.net ; like an English version with the collaboration of Susan Wheadon).

- Wolfgang Trees , Charles Whiting: Enterprise Carnival. The werewolf murder of Aachen's Lord Mayor Oppenhoff. Triangel, Aachen 1982, ISBN 3-922974-02-3 .

Movie

- The Oppenhoff murder case. Werewolves on the ruins of the Nazi Empire. Documentary by Hannes Heer , WDR 1985

Web links

- EXECUTION AT THE AGE OF 16: The Short Life of Heinz Petry

- Hans-Peter Leisten: News about the murder of Oppenhoff. In: Aachener Zeitung. March 29, 2013.

- Picture by Franz Oppenhoff ( Memento from June 20, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Hans-Peter Leisten: News on the murder of Oppenhoff . In: Aachener Zeitung. March 29, 2013.

- ↑ Klaus Schwabe: Aachen at the end of the Second World War: Prelude to the post-war period? In: Historical regional studies. 46, Stuttgart 1997.

- ↑ Saul K. Padover: Experiment in Germany. The Story of an American Intelligence Officer. New York 1946. German under the title: Liegendetektor. Interrogations in defeated Germany in 1944/45. From the American v. M. Fienborck. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-8218-4174-5 .

- ^ SK Padover, LF Gittler, PR Sweet: The Political Situation in Aachen. In: D. Lerner (Ed.): Propaganda in War and Crisis. New York 1951, pp. 434-456. A German translation by M. Propers appeared in 1985 in the brochure 40 Years CDU: How it began. The Padover report: Aachen 1944/45. Edited by the Seniorat History in Student Council 6/1 of the RWTH Aachen and the VVN-BdA Aachen.

- ^ Saul K. Padover: Lie Detector. Interrogations in defeated Germany in 1944/45. Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 196 f.

- ↑ Quote from Klaus Schwabe: Aachen at the end of the Second World War: Prelude to the post-war period? In: Historical regional studies. 46, Stuttgart 1997.

- ↑ Volker Koop: Himmler's last contingent. The Nazi organization "Werewolf". Cologne et al. 2008, pp. 122-136.

- ^ Henning Krumrey : Vole in the archive. In: Focus 40/2008. P. 31 ( online ).

- ^ Peter Longerich: Heinrich Himmler. A biography. Siedler Verlag, Munich 2008, p. 736, fn. 99.

- ↑ City map before 1933 on aachen-stadtgeschichte.de .

- ↑ Description of the Oppenhoff monument on the website of the Ways Against Forgetting campaign (Volkshochschule Aachen), accessed on June 2, 2017.

- ^ Entry on the project page The German Martyrology of the 20th Century of the Archdiocese of Cologne .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Oppenhoff, Franz |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German lawyer, Lord Mayor of Aachen |

| DATE OF BIRTH | August 18, 1902 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Aachen |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 25, 1945 |

| Place of death | Aachen |