Women in the time of National Socialism

|

|

This article or section was due to content flaws on the quality assurance side of the editorial history entered. This is done in order to bring the quality of the articles in the field of history to an acceptable level. Articles that cannot be significantly improved are deleted. Please help fix the shortcomings in this article and please join the discussion ! |

The image of women in the time of National Socialism was shaped by a völkisch - nationalist ideology and emphasized the role of women in society as mothers . The ideal was influenced by other basic features of National Socialist ideologies such as the politics of living space .

In addition to her Aryan descent, the ideal woman should be characterized by character traits such as loyalty , fulfillment of duty , willingness to make sacrifices, ability to suffer and selflessness . For the benefit of the “ national community ”, she should do her duty as a mother. Without a doubt, the Nazi regime remained a strictly patriarchal order, which granted women an ideologically equal position, but not an equal position, but instead assigned a functional role within the “national community”.

Role of women in National Socialism

Conflicts of goals between ideological demands and reality

There were considerable differences and conflicting goals between the official ideology and propaganda guidelines and the actual role of the gender category in National Socialism. In the Weimar Republic, women had mostly voted conservatively, but in the years 1930–1932 also increasingly voted for the NSDAP , also because the majority rejected the emancipatory efforts of the republic. Hans-Ulrich Wehler differentiates between a largely ignoring the role of women in older contemporary history and a radical feminist view of National Socialism as a “women's hell” at the beginning of the 1970s. Against the background of a differentiation according to the historical modernization theory, he sees an official anti-feminism and an indirect promotion of emancipation. The initial measures of discrimination and employment restrictions for women due to labor shortages were increasingly weakened in the mid and late 1930s.

A particular trade-off is seen in the field of agriculture. Farmers and rural women were traditionally involved in gainful employment as “work comrades” and “farm managers” and at the same time subjected to the special demands of the National Socialist blood and soil ideology for their role as the mother of many “hereditary” and “racially pure” children. As part of the compulsory year from 1937 and the compulsory year prescribed for women as so-called “work maids” in the Reich Labor Service , young women were employed as hard-working workers, especially in agriculture. Birth rates rose more slowly in rural areas than in cities.

The conflict of goals is also evident in sport. On the one hand, especially in school sport, a traditional image of women was celebrated in the sense of glorifying the mother's role, on the other hand, in the Olympic Games, women's medals counted just as much as men's medals, so that high-intensity training was carried out in top-class sport. This was the most successful time in sport for Germany, especially because of the success of women.

A biographical novel about Carmen Mory , woman in fur describes a wide variety of images and roles of women in the Third Reich. Carmen Mory, a Swiss journalist and agent, had made a glamorous appearance in Berlin in 1934, flirted with certain Nazi giants and had been recruited as a Gestapo agent . In Paris, she spied on German immigrants and narrowly escaped a death sentence by the French authorities after being exposed. After a pardon and return to Germany, she was arrested by the Gestapo as a double agent and then in the Ravensbrück concentration camp as a dreaded “ block elder ”. Mory committed suicide in Allied custody after the war.

Women in the NSDAP and in politics

The NSDAP saw itself primarily as a “men's party”, and the choice of its symbolism and appearance was correspondingly martial. As early as January 21, 1921, two years after the right to vote for women, the party had decided that women could neither become members of the party leadership nor a member of a governing committee.

After the Reichstag election in March 1933 , which followed the National Socialists' takeover , the proportion of women there fell from an average of six to less than four percent. Even before the first meeting, the KPD was smashed, the SPD banned in June and the remaining parties more or less dissolved themselves. In July the law against the formation of new parties was promulgated (entry into force in Austria in March 1938). Thus, for the November 1933 Reichstag election there was only the NSDAP's unified list. This resulted in an indirect abolition of the right to stand for women until 1945. It had an effect above all in a radical re-masculinization of politics and parties that had become visible since 1928, which was a decisive feature of National Socialist politics. It brought the new beginnings of women in party politics to a standstill and at the same time destroyed the political participation options for women that had been developed up to that point.

After 1933 a whole series of streets in Hanover was named after dead - male - party members. Only with Dora Streit, who was posthumously honored in 1938 , district leader of the Nazi women's union in the Diepholz district , did a politician appear on a street sign in the (later) state capital for the first time in the history of Hanover. The National Socialist Women's Association and the German Women's Work were the only approved women's organizations in the “ Third Reich ”. Their leader and thus the highest ranking woman in National Socialism was Gertrud Scholtz-Klink . The youth organization was the Association of German Girls .

The National Socialist Women's Association and the German Women's Work had four million members and another four million incorporated members. After 1939 their number rose by another two million. In addition, there was the so far little noticed Reich Air Protection Association with 12 million members, 70 percent of whom were female.

The Nazi regime subordinated itself to the sororities of the German Red Cross. All new DRK superiors had to be approved by Gertrud Scholtz-Klink .

Ideology and program

Basics

The social role of women was reduced to the role of mother and guarantor of “steely, combat-ready” offspring. She should be the “source of the nation”, “guardian of strength and the eternal greatness of the nation” and “forerunner of victory”. The National Socialist ideologues saw an essential function of women in the preservation and transmission of “high quality” genetic material .

After the election in March 1932 , which was disappointing for the National Socialists , Hitler tried to win women over to the "movement" and formulated the first core ideas in this context. His head of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, wrote in his diary:

“The Führer develops completely new thoughts about our attitude towards women. They are of eminent importance for the next ballot; for it was precisely in this area that we were attacked hard in the first election. The woman is the man's sex and work companion. It always has been and always will be. Even with today's economic conditions it has to be. Formerly in the field, today in the office. The man is the organizer of life, the woman its help and its executive organ. These views are modern and raise us towering above all German national resentment. "

According to the National Socialist ideal , in contrast to the emancipatory developments in the Weimar Republic, women should again increasingly subordinate themselves to men. Laws severely restricted women’s career and educational opportunities. Encyclopedic folders for housewives were published from 1935 to 1940 under the title I know everything . The Mother and the Foundation of the Mother Cross were institutionalized in 1938 "to underpin the role and value of women".

The liberation was as an invention of " Jewish referred intellect" which destroy the predetermined gender order. At the Nazi Party Congress on September 8, 1934 in Nuremberg, Hitler said: “The word about women's emancipation is a word invented only by the Jewish intellect. We do not feel it is right for women to penetrate the world of men, but we feel it is natural if these two worlds remain separated. "

Joseph Goebbels summarized the program of Nazi women's policy as follows: "The first, best and most appropriate place for women in the family and the most wonderful task that they can fulfill is to give children to their people."

Attractiveness of the national socialist ideology for women

Within the "national community" order, non-Jewish women were given options for action and opportunities for advancement, for example in the numerous Nazi organizations, especially in the Bund Deutscher Mädel (BDM), the National Socialist Women's Union or the NSV. The increasing number of those women who took on responsible tasks in the numerous Nazi associations also promoted independence. As a result, these women also had an active part in racist and anti-Semitic politics, like those, especially young women, who, as committed members of the occupation administration, became independent perpetrators in the occupied eastern areas.

In her memoirs, the psychologist Eva Sternheim-Peters describes the time of National Socialism that the ideological inequality between women and men was not immediately recognizable, but that many women ran along enthusiastically at the time. She speaks of “deeply felt community experiences”, a “new ideal of women” and the “vision of a bright rising sun”, which made National Socialism so dangerous and which it was also attractive to young women.

Annette Kuhn writes in her essay “The perpetrators of German women in the Nazi system” that the Nazi system did not have a difficult time with the majority of German women in the “old” women's movement. The willingness of leaders of the bourgeois women's movement to cooperate with the Nazi state made the transition to ideological integration into the Nazi state seamless. The breach of norms and continuities of 1933 was knowingly covered up by the behavior of those responsible in the old women's organizations through their speeches and writings.

Family policy

activities

National Socialist women's policy was first called family and birth policy. The "genetically healthy" and race-biological "species-appropriate" marriage and family stood as the "nucleus of the national community" under the special protection of the Nazi state. However, for the same genetic and racial biological reasons, separation was also promoted. The “protection of the family” therefore in no way meant respect for the private sphere or a moral commitment, but was subject to a strictly racist idea of expediency and the provision of future workers and soldiers.

At first, women were forced out of working life under the pretext of “double earning”. In 1933, for example, marriage loans were paid out to the husbands - with the condition that the future wife had a job and gave up the job before the marriage. The repayment of the loan decreased by a quarter for each birth of a child. The state budgeted target was thus four children. Women were professionally downgraded: In the school service, female school principals and high school teachers in higher school years were increasingly being replaced by male teachers; Only men taught at boys' schools. Since 1936, however, women’s work has been an “indispensable factor” due to the labor shortage, especially in the armaments industry. Between 1935 and 1939, the proportion of female employees rose from 32.8% to 39%. In 1938, the regulation according to which women had to retire from civil service in the course of the so-called double-income campaign in the event of marriage, was converted into an optional regulation.

The “Mother and Child” aid organization of the National Socialist People's Welfare Association (NSV) , which with 16 million members (1942) was the largest National Socialist mass organization after the DAF , looked after the mothers under the banner of a national birth policy, and single mothers were also looked after , because "racially and genetically high-quality" offspring should not be lost to the people from a racist perspective. In addition to sending mothers to recreation centers, the aid organization built day-care centers, up to 1941 almost 15,000, but the statistics say nothing about their size and quality. Later, especially during the war, the so-called Kinderlandverschickung became a central facility of the relief organization.

In 1939, female school leavers completed a compulsory year in agriculture and in large families . Welfare state stabilization of families who wanted children was introduced. Taxes for childless people were increased, another incentive was the state child allowance of ten Reichsmarks from 1936. Abortions of “genetically healthy German women” were prohibited. In May 1933 there was a tightening by the reintroduced ban on abortion drugs. (§§ 219, 220) In order to “support the abundance of children in the SS ”, from 1935 onwards , the Lebensborn offered racially “valuable” unmarried women help to carry their children to term. In July 1933, the law for the prevention of hereditary offspring promoted sterilization in certain cases, with the authorities having to give their consent. With a change in 1935, termination of pregnancy was also possible in such cases. With the ordinance on the protection of marriage, family and motherhood of 1943, the penalties for termination of pregnancy (Section 218) were increased and persons “of non-German ethnicity” were exempted from the prohibition on termination of pregnancy. If a “racially inferior woman” was pregnant, she was often pressured to have an abortion.

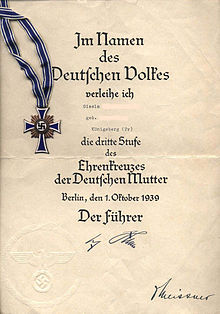

In 1936, child benefit of ten Reichsmarks per month was introduced for the first time from the fifth child under 16 years of age for families whose monthly income did not exceed 185 Reichsmarks. These restrictions were gradually withdrawn over the next few years, until in December 1940 all families received child benefit from the third child. The Mother Cross was awarded for the first time on May 21, 1939 . From then on, women with “above-average childbearing performance” received the German Mother's Cross of Honor on Mother's Day: bronze for four children, silver for six children and more, and gold for eight or more children. Nevertheless, in 1939 there were 1.3 children in an average marriage.

Role of women in the economy

In 1933 there were 11.6 million and in 1939 14.6 million women who were gainfully employed. This meant that 52 percent of all women between the ages of 15 and 60 in Germany had wage or salary work, whereby most women were still employed in agriculture and housekeeping, only afterwards in the service sector and very few in industry.

As expected, the employment rate of unmarried women was 88 percent, much higher than that of married women, at around a third.

In 1943, when the labor shortage was very urgent, Hitler spoke out against the increased inclusion of women in armaments production for ideological reasons and also refused to demand that wages for women be equal to those for men. Nevertheless, in some areas where women had become indispensable, for example as conductors in the transport company, women asserted that they were paid the same amount as their male predecessors. Due to the clear shortage of doctors, the restrictions on women studying medicine fell during the war years, so that the proportion of women doctors in the medical profession as a whole, which had been a mere 6.5 percent in 1933, more than doubled by 1944.

Legal position

The so-called obedience paragraph §1354, which gave the man the right to decide in marriage matters , had been anchored in the civil code since 1900 . When Adolf Hitler came to power , some of the achievements of the Weimar Republic were reversed. While men could be appointed civil servants for life from the age of 27, an age of 35 was required for women.

On July 22, 1934, under the leadership of Otto Palandt, a new judicial training ordinance came into force. On December 20, 1934, the law to change the bar code followed , according to which women were no longer admitted as lawyers because that would have meant a "breach of the sacred principle of the masculinity of the state". After the new laws were passed, Palandt unequivocally stated that it was “up to the man to uphold the law”.

Testimonies

In 2014 there was an English translation and in 2015 the German original Wolfhilde von Koenig's diary of a young National Socialist was published .

In 2017, the historian Katja Kosubek published a collection of essays that German women had written in 1934 on the subject of the "personal life story of a National Socialist" under the title Just as consistently socialist as national . The background to the creation of these essays was a mock competition initiated by the American sociologist Theodore Abel to obtain text material for his research on the German zeitgeist. All material is also available online via the Hoover Institution website at Stanford University .

Quotes

- "The world of women [be] the family, her husband, her children, her home" (Adolf Hitler, Munich 1936)

- “I do not believe that it is a degradation of women when she becomes a mother, on the contrary, I believe that it is her highest elevation. There is no greater nobility for women than to be the mother of the sons and daughters of a people. "(Adolf Hitler, 1935)

- “I would be ashamed to be a German man if ever, in the event of a war, even a woman had to go to a front! [...] Because nature did not create women for it. "(Adolf Hitler, Munich 1935)

- “The inevitable consequence of female mass study and the penetration of women into all male professions is blue stocking culture and female domination. [...] ".

"What a tragedy it would be if the German people, the manliest people in the world, the people of poets and thinkers, the pioneers of cultural and technical progress with their more than thousand-year-old culture, fell victim to feminism and perished as a result of this popular degeneration!" Josef Rompel: The woman in the man's living space, emancipation and state welfare. Darmstadt 1932, p. 6 and 43) - “However, the achievable goal must be defined: the mother should be able to devote herself entirely to her children and family, the woman to the man, and the unmarried girl should only be dependent on jobs that correspond to the female character. Apart from that, every professional activity should be left to the man. ”(Rudolf Frick in Völkischer Beobachter . June 12, 1934)

- “The German women want [...] mainly their wives and mothers, they don't want to be comrades, as the red people happy to try to convince themselves and them. You have no longing for the factory, no longing for the office and also no longing for parliament. A cozy home, a dear husband and a group of happy children are closer to their hearts. ”(Curt Rosten: The ABC of National Socialism. Berlin 1933, p. ??)

See also

literature

- Elizabeth Harvey: The East Needs You! Women and National Socialist Germanization Policy . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-86854-218-9 (review by Franka Maubach ).

- Christiane Goldenstedt: Alice Salomon (1872-1948) and Hilde Lion (1893-1970). In: Spirale der Zeit: Writings from the House of Women's History Bonn. No. 5, 2009, pp. 73-77.

- Dorothee Klinksiek: The woman in the Nazi state. DVA, Stuttgart, 1982, ISBN 3-421-06100-9 .

- Nicole Kramer: People's comrades on the home front: mobilization, behavior, memory. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2011, ISBN 978-3-525-36075-0 .

- Annette Kuhn , Valentine Rothe: Women in German Fascism. 2 volumes. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1982, ISBN 3-590-18013-7 .

- Massimiliano Livi: Gertrud Scholtz-Klink: The Reichsfrauenführer ; Political spheres of action and identity problems of women under National Socialism using the example of the “Leader of All German Women”. Doctoral thesis University of Münster 2004. Lit, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-8258-8376-0 .

- Sybille Steinbacher (ed.): Volksgenossinnen: Women in the NS-Volksgemeinschaft. Wallstein, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-8353-0188-7 .

- Rita Thalmann : being a woman in the Third Reich. Ullstein, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-548-33081-9 (first edition: Hanser, Munich 1984, ISBN 3-446-13579-0 ).

- Ludger Tewes : Red Cross Sisters: Their deployment in the mobile medical service of the Wehrmacht 1939–1945. Schöningh, Paderborn 2016, ISBN 978-3-506-78257-1 .

Women as contributors:

- Christina Herkommer: Women under National Socialism - victims or perpetrators? A controversy in women's studies as reflected in feminist theory formation and the general historical processing of the Nazi past. M-Press, Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-89975-521-3 .

- Kathrin Kompisch: Perpetrators: Women under National Socialism. Böhlau, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-412-20188-3 .

- Wendy Lower : Hitler's helpers: German women in the Holocaust. Hanser, München 2014, ISBN 978-3-446-24621-8 (from the English by Andreas Wirthensohn; original: Hitler's Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Boston 2013, ISBN 978-0-547- 86338-2 ).

Theoretical work:

- Ljiljana Radonic: The peaceful anti-Semite? Critical theory about gender relations and anti-Semitism. Lang, Frankfurt / M. 2004 ISBN 978-3-631-53306-2 .

Women and Resistance:

- Frauke Geyken: We didn't stand aside: women resisting Hitler. Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-65902-7 .

- Florence Hervé : Women in the Resistance 1933–1945 Düsseldorf. Ed .: Wir Frauen e. V., Rosa Luxemburg Foundation NRW e. V., DGB Region Düsseldorf-Bergisch Land. Cologne 2012, ISBN 978-3-89438-493-7 .

- Florence Hervé (ed.): With courage and cunning. European women in the resistance against fascism and war, Cologne 2020, Papy Rossa Verlag Cologne, ISBN 978-3-89438-724-2 .

- Gerda Szepansky: Women resist: 1933–1945. Fischer, Frankfurt / M. 1983, ISBN 3-596-23741-6 .

- Christl Wickert (Hrsg.): Women against the dictatorship: Resistance and persecution in National Socialist Germany (= writings of the German Resistance Memorial Center Berlin. ) Berlin 1995.

Web links

- Carolin Bendel : The German woman and her role in National Socialism. In: The future needs memories . October 3, 2007.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Michael Wildt : Volksgemeinschaft. In: bpb.de. Federal Agency for Civic Education, May 24, 2012, accessed on January 14, 2020 (part of National Socialism: Rise and Rule ).

- ↑ Claudia Koonz: Mothers in the Fatherland. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1994, p. ??.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society. Volume: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949. Beck, 2003, ISBN 3-406-32264-6 , pp. ??.

- ^ A b Daniela Münkel : National Socialist Agricultural Policy and Everyday Farmers' Life. Campus, Frankfurt / M. 1996, ISBN 3-593-35602-3 , p. 427.

- ^ Daniela Münkel: National Socialist Agricultural Policy and Everyday Farmers' Life. Campus, Frankfurt / M. 1996, ISBN 3-593-35602-3 , pp. ??.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society. Volume: From the beginning of the First World War to the founding of the two German states 1914–1949. Beck, 2003, ISBN 3-406-32264-6 , pp. 755 ff.

- ^ Daniela Münkel: National Socialist Agricultural Policy and Everyday Farmers' Life. Campus, Frankfurt / M. 1996, ISBN 3-593-35602-3 , p. 444.

- ↑ Michaela Czech: Women and Sport in National Socialist Germany: An investigation into the reality of female sport in a patriarchal system of rule (= contributions to sport and society. Volume 7). Tischler, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-922654-37-1 , p. ??.

- ^ Arnd Krüger : “Sieg Heil” to the most glorious era of German sport: Continuity and change in the modern German sports movement. In: International Journal of the History of Sport. Volume 4, No. 1, 1987, pp. 5-20, here pp. ??.

- ↑ Lukas Hartmann: Woman in Fur: Life and Death of Carmen Mory. Novel. Nagel & Kimche, Zurich 1999, ISBN 3-312-00250-8 , p. ??.

- ↑ Elisabeth Perchinig: On practicing femininity in a terror context: Girl adolescence in the Nazi society , profile, 1996, ISBN 978-3-89019-382-3 , p. 45.

- ↑ Mechtild Fülles: women in the party and Parliament. Science and Politics, Cologne 1969, p. ??.

- ↑ Kirsten Heinsohn: Contributions to the history of parliamentarism and political parties , Volume 155.Droste, 2010, ISBN 978-3-7700-5295-0 , p. 255.

- ^ NN : Hannoversche Geschichtsblätter . New episode, volume 52. 1998, p. 435 ( view of quotations in the Google book search).

- ^ Gabriele B. Clemens: Mobilized Comrades: Millions of women were involved in the Third Reich - which received little attention after 1945. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . 23 July 2012, p. ??.

-

↑ Red Cross Sisters: the nursing professionals: Humanity - the idea lives. Ed .: Association of Sisterhoods of the German Red Cross e. V. Olms, Hildesheim 2007, pp. ??.

Ludger Tewes: The Red Cross Sisterhoods in National Socialism and in the Second World War (1933-1945). ISBN 978-3-487-08467-1 , pp. 97–122, here p. ??. - ↑ Joseph Goebbels: Diaries. Volume 2. 2nd edition. Piper, Munich 2000, page 637.

- ↑ The ideal of women in the new state. In: Cassie Michaelis, Heinz Michaelis, Willy Oscar Somin: The brown culture. A mirror of documents. Europa, Zurich 1934, pp. 15–28.

- ↑ Verena Friederike Hasel: Eva Sternheim-Peters on the Nazi era: "I didn't run with them, I stormed with enthusiasm" In: Tagesspiegel.de . April 30, 2015, accessed January 14, 2020 .

- ^ Anette Kuhn: The perpetration of German women in the Nazi system: Traditions, dimensions, changes. In: Women under National Socialism. Hessian State Center for Political Education, p. 5.

- ^ Christiane Wilke: Research, teaching, protest: 100 years of academic education for women in Bavaria. Accompanying volume for the exhibition. Ed .: State Conference of Women's and Equal Opportunities Officers of Bavarian Universities. Utz, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-8316-0273-5 , p. ?? ( PDF: 3 MB, 120 pages on utzverlag.de ( Memento from December 3, 2013 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ § 1a in the Reichsbeamtengesetz of March 31, 1873 as amended by the law of June 30, 1933.

- ↑ Katja Kosubek (ed.): "As consistently socialist as national": Old fighters of the NSDAP before 1933 . Wallstein, Göttingen 2017, ISBN 978-3-8353-3057-3 .

- ^ Christian Staas: Women in National Socialism: Your Struggle. In: The time. July 9, 2017, accessed January 14, 2020 .

- ^ Hoover Institution at Stanford University : Digital Collections Home. Retrieved January 14, 2020 .