Women praise

Heinrich von Meißen , called Frauenlob (* between 1250 and 1260 in Meißen ; † November 29, 1318 in Mainz ) was an influential poet of German vernacular, whose programmatic stage name probably comes from his body of Mary . The frouwe praised therein is Mary , Queen of Heaven .

Live and act

The poet, who came from Meissen , stayed in Bohemia around 1276/78, and in 1299 he served - documented as ystrio dictus Vrowenlop - for Duke Heinrich of Carinthia . Frauenlob wrote for King Rudolf I of Habsburg , King Wenceslaus II of Bohemia , the King of Denmark , Prince Wizlaw III. von Rügen , Archbishop Giselbert von Bremen and others. Some sayings are dedicated to the Rostock Knight Festival of 1311. Most recently, he lived as a protégé of Peter of Aspelt , an archbishop and former Chancellor Wenceslas II., In Mainz . After his death he was buried in the eastern cloister of Mainz Cathedral .

In 1774 his gravestone was destroyed during construction work, it was replaced by Johann M. Eschenbach in 1783 and again by Ludwig Schwanthaler in 1841/42 .

Frauenlob was one of the most influential German-speaking poets of the 14th century. His work has come down to us in numerous manuscripts. He was so influential that many imitated his style. Overall, this always raises the question of the “authenticity” of the women's praise, as it is often not clear whether it is his own authorship. His work includes 13 Minnelieder , the " Marienleich ", also known as "Frauenleich", the "Minneleich" and the "Kreuzleich", the argument between Minne and the world as well as a large number of singing sayings in a multitude of different tones. There is no complete consensus about the exact number, estimates are around 300 sayings in probably 15 own tones.

As his role model, Konrad von Würzburg had the greatest influence on Frauenlob's work. Despite all the admiration for his role model, Frauenlob's poetic style is nonetheless independent. His language is artistic, elected and rich in images, while his tones are complexly structured. The image as a poetic medium was established by Frauenlob in a special way and is an outstanding characteristic of his poetic inventive talent. He was a master of the " floral style ".

Frauenlob became known through his corpse and already experienced admiration and patronage during his lifetime like Walther von der Vogelweide in a comparable way . Later in the 15th century Frauenlobstraße was from the meistersängerischen revered vocal care as one of the great masters and many Master songs were written with slight variations in his tones and his manner in his honor, in part, put into the mouth or attributed in manuscripts that time.

In research, women praise and rainbows are considered to be the last great song poets. Helmut Tervooren speaks of the fact that women's praise can be seen as “a kind of vanishing point”. This means that through the praise of women, the entire richness of facets of courtly sanguine in its "ultimate consequence" was revealed before there was a break in the "culture of tradition", as it was increasingly over with elaborate lyrical manuscripts and collections in the courtly environment, while the bourgeois, master-singer manuscripts - now mostly paper manuscripts - came up.

To the question of authenticity

In order to gain insight into the question of authenticity, the manuscripts must be compared. It must be analyzed what the special characteristics of the style Frauenlobs are. Deviations from this become indications that speak against his authorship. One who did this and at the same time one of the most influential men in women's praise research was Helmuth Thomas . In 1939 in the specialist journal Palaestra 217 - Investigations and Texts from German and English Philology "Investigations on the Tradition of the Spruchdichtung Frauenlobs", he compiled an overview of Frauenlob's work in the various manuscripts based on his authenticity criteria and presented the arguments for talk about its compilation. Thomas Analysis is still the basis for the research and reconstruction of Frauenlob's work.

Sources of tradition

The sources of potential transmission are numerous. According to Helmuth Thomas, the most important text witnesses of the work are:

- the Jenaer Liederhandschrift (J) with its supplements (Jn1, Jn2)

- the Great Heidelberger Liederhandschrift , also called Manessische Handschrift (C)

Other sources are:

- the Kolmarer Liederhandschrift (k - also designated with the letters t, K and ko)

- the Viennese manuscript (W)

- the Breslau manuscript fragments

- the appendices of the Heidelberg manuscript (H and R)

- the Würzburg manuscript (E)

- the Niederrheinische Liederhandschrift (s)

- the Möser fragments of a Low German song manuscript (m)

- the Hague manuscript

- the Weimar manuscript

- the Donaueschingen song manuscript (u)

- the Wilten master singer manuscript (w)

- the Munich master singer manuscript (s)

- the Prague prayer book of Charles IV.

- a letter from Johann von Neumarkt

- further Mastersinger manuscripts

The most important sources of tradition in detail

Courtly manuscripts

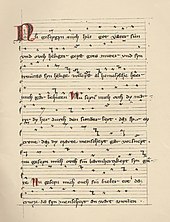

Jena song manuscript (J)

The Jena song manuscript contains what is probably the most unadulterated collection of singing sayings by women. There are 3 records in total in the manuscript. A relatively large section of 55 Proverbs by the main scribe of the manuscript from the mid-14th century and 2 supplements. Due to 5 lost sheets of the manuscript, the beginning of the Frauenlob section has not been preserved either, the loss cannot be clearly measured, the theories diverge - from great loss to the fact that the sheet failure only causes texts that have been handed down elsewhere to be lost have gone. The first addendum was made in the margin by another scribe shortly after the manuscript was written and comprises 30 stanzas of the long tone. This section is denoted by Jn1. The second addendum at the bottom of a page includes 3 proverbs in a delicate tone and was probably made in the 15th century - it is called Jn2. A special quality of the Frauenlob tradition through this manuscript is the comparatively easy correctability of the spelling mistakes.

Great Heidelberg Song Manuscript (C)

The Große Heidelberger Liederhandschrift or Manessische Handschrift records the woman's corpse and 30 sayings in long, short and green tones. The authorship of Frauenlobs is particularly assured, as his name is recorded several times in the manuscript. Master Heinrich vrouwenlop is already mentioned here. Both the corpse of a woman and the last two sayings, however, appear distorted in the wording up to entire paragraphs compared to J according to Thomas, whereby the corpse of a woman seems even closer to the origin compared to the last sayings in the collection. In previous analyzes, Pfannmüller concluded that the originals for the writer of the manuscript were poor - especially with the last two sayings. However, the remaining sayings are well preserved.

Würzburg manuscript (E)

In the Würzburg manuscript, contrary to the promises of the register, only the corpse of a woman and a saying in a long tone are handed down, since chapters 2-14 have been lost. According to Thomas, the handwriting is also considered to be rather unreliable.

Viennese manuscript (W)

The Viennese manuscript, which is made up of several independent traditions, contains the end of the woman's body and the beginning of the Latin translation in the first part. In the second part three sayings of women's praise in green tone and another three in choke throttle tone. According to the headline in the manuscript, the sayings in the green tone come from shortly before Frauenlob's death. However, the sayings deviate formally from other sayings in the green tone in a way that occurred in the later Meistersinger tradition. According to Thomas, this is an indication that the sayings in the green tone should not be regarded as secure. The three sayings in the choking throttle tone, on the other hand, can be seen as genuine by comparison with the Weimar manuscript f.

Master-singer manuscripts

Kolmar song manuscript (k)

The Kolmar song manuscript, which was created in the 15th century, contains at least 32 genuine sayings from Frauenlobs and his corpse of Mary, which is placed separately in front of the manuscript. This suggests that Frauenlob was highly valued by the authors of this manuscript, which is a master-singer. In addition to the corpse of Mary and another corpse, the female praise corpus of k includes several hundred sayings in the super-soft tone, long tone, gaggle tone, frog-like, golden tone, dog-wise and mirror-like, forgotten tone, new tone, tender tone, green Ton, in the knight manner and in the train manner. The question of authenticity or the question of authorship is particularly complex in k due to the mastersingers editorial staff and not all of the authors' comments are reliable. For example, the letter style in the manuscript k Frauenlob and Regenbogen is counted together, but can be assigned to rainbow by comparing it with the Große Heidelberger Liederhandschrift C. Overall, it can be assumed that some of the sayings in women's praise tones were written by members of the master-singer tradition in his manner. Likewise, due to the background of the master-singer's editorial distortion of the original material, the relationship between the praise of women and the rainbow cannot be clearly documented, as it could also be a subsequent inauthentic staging.

Weimar paper manuscript (noun)

The Weimar paper manuscript, which presumably originated in Nuremberg between 1455 and 1475, is one of the larger traditional sources for Frauenlob. It contains 3 corpses, the argument about love and the world and the songs as well as 273 sayings in its tones. Since it is also a manuscript edited by master singers, the question of text authorship for the Proverbs arises in the same way as in the case of the Kolmar song manuscript. However, the degree of distortion is stronger than that. For research on women's praise, the Weimar paper manuscript is therefore particularly useful for comparing it with other manuscripts and fragments and for confirming and identifying other women's praise items. In comparison to k, the sorting in bar form is not strictly adhered to either. Between the other real tones of Frauenlob there are two tones that have not been handed down in manuscripts from the 14th century: the New Tone and the Forgotten Tone.

Wilten master singer manuscript (w)

Another manuscript edited by master singers is the Wilten manuscript. Like the Kolmar song manuscript, it also takes first place in her praise for women. There are tones in the long, new and tender tone as well as in the choking throttle tone, in the green tone and in the knight, play and move style. The authors of the manuscript also attribute works by authors such as Konrad von Würzburg and Reinmars von Zweter to him, although this can be excluded by comparison with other sources.

Munich master singer manuscript (s)

The Munich master singer manuscript gives ten bare tones in women's praise tones: the green, tender, long and new tone. However, only a few scattered stanzas of these bares are genuine women's praise. They deviate from both the manner and the topic of women's praise and can therefore be regarded as spurious.

Fragments

Wroclaw manuscript fragments

The Breslau manuscript fragments are 16 fold strips written on, which can be put together on 2 sides. In addition to saying fragments in the choke throttle tone and not clearly identifiable tones, there are 3 sayings in the golden tone and another three in the delicate tone. By comparing it with other manuscripts (J, w, f and k), however, Frauenlob's authorship can be regarded as certain.

Polemic about women's praise

From the texts handed down by Frauenlob and his poet colleagues, a picture of Heinrich von Meissen, who tends to boast of himself, emerges several times, whose colleagues counter his highly praised self-portrayals. Burghart Wachinger summarizes this mutual reference in several chapters. A distinction must be made between the polemics based on real women praise and the controversial poems that the poet and especially his colleague Rainbow were at least possibly put into the mouth. The latter is based on the extensive material from the Meistersinger manuscripts, in which, however, even in this context, the indications in the question of authenticity speak against an original text authorship by women. It must therefore be assumed that the dispute between the “masters” Frauenlob and Regenbogen arising from the Meistersinger manuscripts is a staged fiction of the master-singer tradition.

wip-vrowe dispute

The wip-vrowe dispute deals with the pros and cons of the usage of the terms wip and vrowe . The dispute probably began with the following stanza in the long tone of women's praise:

The stanza which triggered the wip-vrowe dispute

Maget, wip and vrouwe - da lit aller saelden goum.

maget is a boum of

the first kiusche blomen

from ir maget komen,

Heilrich ursprinc, des wesen wesen. all senses gomen,

the customers do not have the süezen kind vollobn the kiuschen megede.

But if the süezen blomen lust is pissed off by menlich cunning

, they are called wip denne.

if I rehte recognize

the nam W unn I rdisch P I Aradis of debt call.

Praise you, wip, through vreudennam and through din biltbehegede.

Even if she humanely begat

and vruht gives birth, alrest the gratitude

that the highest phat has

achieved:

vrowe is a name, ir billich lat,

the use uf al ir becomes stat,

vrou is a name, people are quarreled with lust whatever .

Translation

virgin, woman and mother: in them all good strength resides.

The virgin Maget is a tree:

blossoms of the first chastity

that arise from her virginity,

the beginning of everything good, the epitome of everything that is desirable. All the powers of the mind

could not sufficiently extol the lovely manner of the chaste Virgin.

But when the splendor of the magnificent flowers has fallen off through male cunning,

then they are called Wip.

If I understand it correctly,

I have to interpret the name as W onne I rdisch P aradies.

Praise you, Wip, for the joys of your name and your figure.

When it lives up to the human way

of life and gives birth to the fruit of life, only then has it achieved its destiny,

the highest goal

:

Vrowe is a name that is rightly given to it.

She is highly respected for her merit.

Vrowe is a name that makes the "sense of man" promise joy (more precisely: to hunt).

interpretation

According to Frauenlob, the highest honorific name for the female sex is the designation vrowe . The honor of the vrowe includes all the honor of wip - but not the other way around. Frauenlob clarifies this argument in another stanza. His opponents are offended by this argument that the term wip is sanctified by the usage of Jesus Christ and that the praise of women with its vrowen praise for the holiness of the Son of God goes wrong. The counterstrophes, however, never fully take up Frauenlob's argumentation, which is extraordinarily complex for such poetry. Frauenlob's later argument that both wip and vrowe can equally be scolded as unwip is already in the core of his initial stanzas. In the wip-vrowe dispute, Frauenlob presents himself as a learned, vernacular didactic , whom one would certainly like to admit that he has acquired theoretical knowledge about what he is writing about. The names of his opponents cannot be clearly identified in their authorship of the counterstrophes. The name Rumelant and probably also the authorship of the rainbow can be mentioned as certain .

Polemic about women's praise for self-expression

Frauenlobs Selbstpreisung

Waz he gesanc Reinmar and von Eschenbach,

waz he gesprach

the von der Vogelweide -

with vergoltem dress

I Vrowenlop Verguld ir sanc when I assessment notices iuch:

they han sung by the feim, the grunt han si verlazen.

Uz kezzels basic gat min art, so giht min munt.

I tuon iu kunt

with words and with doenen

ane sunderhoenen:

one should still mins sanges shrine even rilichen kroenen.

si han gevarn the small stic bi artsy strazen.

Whoever sans and still sings

- bi green wood a fulez bloch -

then I am still a

master.

I also wear a yoke for

the senses , because of this I am a cook for the arts.

Min word, min doene never entered the wrong senses.

Translation

What Reinmar and von Eschenbach

ever sang, what

von der Vogelweide ever said:

with a pompous golden dress

I gild their singing , thanks to women, as I am now showing you:

They only sang from the foam of the surface, they neglected the ground .

My art comes from the bottom of the kettle, that's what I stand for.

I announce to you

with words and sounds

without exaggeration:

The praise of my song should be adorned with a (valuable) crown.

Others only walked the narrow paths alongside the streets of the great arts.

Anyone who has ever sung and will still sing

- a lazy branch on the green wood -

I am

the master of them all.

I also bear the yoke of the mind

and I am also a cook of the arts.

My words and tones never left the place of good art.

interpretation

With this stanza of undisguised boasting, Frauenlob seeks its equal. He presents himself as the king of poets, and although he did not hold such a position at the time the verse was written, this saying fits in with the legend that he later became in the master-singer tradition. However, he provoked a sharp polemic reaction among his contemporaries. Above all, this woman's praise criticizes the presumption of standing above the deceased “masters” such as Walther von der Vogelweide, Reinmar and Wolfram von Eschenbach. Contrary to Ettmüller's original opinion that Frauenlob's saying of self-boasting is a defense against his critics in the wip-vrowe dispute, Frauenlob's saying is the starting point for a new challenge to his contemporaries.

Quarrel between women praise and rainbow

In the master-singing manuscripts, many poems have come down to us that stage a fictitious dispute that the authors of the manuscripts may have put into the mouths of the masters. The other part - at least in C - is made up of “real” stanzas, and here, too, a distinction must be made between the traditions of manuscripts from the courtly environment of the 14th century and those of master-singer manuscripts. Formally, many of the master-vocalist poems are clearly not penned by the “masters”; instead, these actors appear immediately. According to those legends, Rainbow was a blacksmith who began to argue with the poet Frauenlob. This can already be found in a miniature of the Great Heidelberg Song Manuscript. The greatest sources of tradition for this staged singing war are the Great Heidelberg Song Manuscript and the Kolmar Song Manuscript. In C there are alternating stanzas of women's praise and rainbow, which combine to form a kind of singers' war in which the two vie for who is the better. Burghart Wachinger has summarized the poems that can be seen in this tradition in his book Sängerkrieg . Among them are the nine stanzas from k in Regenbogen's letter tone , which together make up the so-called War of Würzburg . Women praise and rainbows argue in this about whether men or women have priority. The judges of this tournament of artists are called merker , which is a reference to the competitive traditions of the master singers .

Monuments, reception

For the Berlin Siegesallee designed Reinhold Begas a marble bust Frauenlobs as a side figure of the monument group 8 to the central statue of Waldemar ( the Great ) , unveiled on 22 March 1900's.

In Mainz, on the banks of the Rhine (near Frauenlobstraße), you can find a sculpture by Richard Hess that depicts Frauenlob in his boat at about half life size.

The history painter Alfred Rethel created the romantically inspired drawing Frauenlobs funeral in the 1840s .

See also

The minstrel Margrave Heinrich III should not be confused with praise for women . von Meißen , whose songs have come down to us partly in the same manuscripts.

literature

Text output

- Karl Stackmann , Karl Bertau (Ed.): Frauenlob (Heinrich von Meissen): Leichs, Sangsprüche, Lieder. 2 volumes (= Abh. D. Akad. D. Wiss. In Göttingen, Philol.-hist. Kl. III. 119–120) Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1981, ISBN 3-525-82504-8 .

- Dictionary for the Göttingen women's praise edition. Edited by Karl Stackmann with the assistance of Jens Haustein. (= Abh. D. Akad. D. Wiss. In Göttingen, Philol.-hist. Kl. III; Volume 186) Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1990, ISBN 3-525-82472-6 .

- Jens Haustein, Karl Stackmann (ed.): Singing sayings in tones of women's praise. Supplement to the Göttinger Frauenlob edition. 2 parts, with the collaboration of Thomas Riebe and Christoph Fasbender. (= Abh. D. Akad. D. Wiss. In Göttingen, Philol.-hist. Kl. III; Volume 232) Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2000, ISBN 3-525-82504-8 .

Recordings on sound carriers (selection)

- Frauenlob (Heinrich von Meissen, approx. 1260–1318) - The Celestial Woman / Frauenlobs Leich, or the Guldin Fluegel, in Latin: Cantica Canticorum , Sequentia. Ensemble for music of the Middle Ages , Deutsche Harmonia Mundi / BMG Classics 2000

Research literature

- Michael Baldzuhn: From the sang line to the master song. Investigations into a traditional literary context on the basis of the Kolmar song manuscript . Niemeyer, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-484-89120-3 .

- Thomas Bein: Sus hup all dear vrevel. Studies on Frauenlobs Minneleich (= European University Writings , Series 1: German Language and Literature; Volume 1062). Lang, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1988, ISBN 3-8204-1438-X .

- Harald Bühler: Women's Praise Index. With a foreword by Karl Bertau . Palm & Enke, Erlangen 1985.

- Sebastian Cöllen: Filled flower art. A cognitive-linguistic-oriented study of the metaphors in Frauenlobs Marienleich. Uppsala University, Uppsala 2018, ISBN 978-91-506-2691-9 (Diss .; urn : nbn: se: uu: diva-347182 ).

- Josephine Graf-Lomtano: The minstrel Heinrich Frauenlob . In: Reclams Universum 35.1 (1919), pp. 112-114. With 3 fig.

- Patricia Harant: Poeta Faber. The handicraft poet at Frauenlob. Texts, translations, text criticism, commentary, etc. Metaphor interpretations (= Erlanger studies; Volume 110). Palm & Enke, Erlangen / Jena 1997.

- Jens Haustein (ed.), Karl Stackmann: Frauenlob, Heinrich von Mügeln and their successors . Wallstein, Göttingen 2002, ISBN 3-89244-388-2 .

- Jens Haustein, Ralf-Henning Steinmetz: Studies on Frauenlob and Heinrich von Mügeln. Festschrift for Karl Stackmann on his 80th birthday (= Scrinium Friburgense; Volume 15). Universitätsverlag, Freiburg / Switzerland 2002, ISBN 3-7278-1350-4 .

- Christoph Huber: Word is a sign of things. Investigations into linguistic thinking of Middle High German saying poetry to Frauenlob . Artemis, Munich 1977.

- Susanne Köbele: Women's praise songs. Parameters of a literary historical location determination (= Bibliotheca Germanica; Volume 43), Francke, Tübingen / Basel 2003.

- Claudia Lauer, Uta Störmer-Caysa (eds.): Handbuch Frauenlob. Universitätsverlag Winter, Heidelberg 2018, ISBN 978-3-8253-6952-1 .

- Cord Meyer: The "helt von der hoye Gerhart" and the poet Frauenlob. Court culture in the vicinity of the Counts of Hoya. Library and information system of the University of Oldenburg, Oldenburg 2002, ISBN 3-8142-0839-0 ( urn : nbn: de: gbv: 715-oops-6052 ).

- Anton Neugebauer: "The singer's picture lives" - praise for women in art. Pictures of Heinrich von Meissen from the 14th to the 20th century (= research contributions from the Episcopal Cathedral and Diocesan Museum. 4). Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2018, ISBN 978-3-7954-3375-8 .

- Anton Neugebauer: Frauenlob and his grave: 700th anniversary of the death of the Mainz poet Heinrich von Meißen. Women's praise weeks in the Dommuseum. In: Mainz. Quarterly issues for culture, politics, economics, history. Vol. 38 (2018), H. 3, ISSN 0720-5945 , pp. 22-27.

- Barbara Newman: Frauenlob's Song of Songs: A Medieval German Poet and His Masterpiece. Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA 2006.

- Brunhilde Peter : The theological-philosophical world of thoughts of Heinrich Frauenlob . Speyer 1957, DNB 453741312 (diss.).

- Oskar Saechtig: About the pictures and comparisons in the sayings and songs of Heinrich von Meißen. Marburg 1930, DNB 571137075 (diss.).

- Werner Schröder (Ed.): Cambridge “Frauenlob” colloquium 1986 (= Wolfram Studies; Volume 10). Schmidt, Berlin 1988.

- Guenther Schweikle: Minnesang (= Metzler Collection; Vol. 244). 2nd corrected edition Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1995.

- Ralf-Henning Steinmetz: Love as a universal principle at Frauenlob. A vernacular world draft in European poetry around 1300 . Niemeyer, Tübingen 1994.

- Helmut Tervooren: Sangspring poetry . Metzler, Stuttgart 2001.

- Helmuth Thomas: Investigations into the transmission of the verse poetry Frauenlobs (= Palaestra; Volume 217). Academic Publishing Company, Leipzig 1939, DNB 362884714 .

- Burghart Wachinger: Singers' War. Investigations into the poetry of the 13th century . Beck, Munich 1973.

- Shao-Ji Yao: The example use in chant poetry. From the late 12th century to the beginning of the 14th century . Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2006, ISBN 3-8260-3348-5 .

Biographies

- Bert Nagel: Praise to women. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 5, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1961, ISBN 3-428-00186-9 , pp. 380-382 ( digitized version ).

- Karl Bartsch : Praise to women . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1877, pp. 321-323.

- Karl Bertau : Heinrich "von Meißen" (woman praise) . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 4, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-7608-8904-2 , Sp. 2097-2100.

- Franz Viktor Spechtler: Heinrich von Meißen (called Frauenlob). In: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon . Online edition, Vienna 2002 ff., ISBN 3-7001-3077-5 ; Print edition: Volume 2, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-7001-3044-9 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Frauenlob in the catalog of the German National Library

- Text by Owê herzelîcher leide with a New High German translation

- Marc Lewon: Here's looking at miniatures: Master Frauenlob and “Lady Music” - An interpretation of the Frauenlob miniature in Codex Manesse.

- “The singer's picture is alive”. Heinrich von Meißen, called Frauenlob 1318–2018 . Cabinet exhibition in the Cathedral and Diocesan Museum Mainz .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gustav Faber : I think of Germany ... Nine journeys through history and the present . Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1975. ISBN 3-458-05898-2 . P. 16.

- ↑ Karl Bartsch : Frauenlob . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1877, pp. 321-323.

- ↑ "The singer's picture is alive" . Flyer for the anniversary exhibition in the Cathedral and Diocesan Museum Mainz, accessed on November 20, 2018 (PDF; 3.21 MB)

- ↑ Tervooren, 2001, p. 127.

- ↑ Tervooren, 2001, p. 127.

- ↑ cf. Thomas, 1939. Contents

- ↑ Thomas, 1939, pp. 2-26.

- ↑ Thomas, 1939, pp. 27-43.

- ↑ Thomas, 1939, pp. 81-85.

- ↑ Thomas, 1939, pp. 43-53.

- ↑ Baldzuhn, 2002, pp. 142–217.

- ↑ Thomas, 1939, pp. 91-123.

- ↑ Thomas, 1939, pp. 139-142.

- ↑ Thomas, 1939, pp. 142-144.

- ↑ Thomas, 1939, pp. 53-64.

- ↑ cf. Wachinger, 1973, pp. 182-298.

- ↑ HMS III, p. 114 f .; Ettmüller 150

- ↑ cf. Huber, 1977, p. 127 ff.

- ↑ cf. Wachinger, 1973, pp. 188-246.

- ↑ HMS II, p. 334a; Ettmüller 165

- ↑ cf. Wachinger, 1973, pp. 247-279.

- ↑ cf. Wachinger, 1973, pp. 280-298.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Women praise |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Heinrich von Meissen; Frouwenlop |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Middle High German minstrel and song poet |

| DATE OF BIRTH | between 1250 and 1260 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Meissen |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 29, 1318 |

| Place of death | Mainz |