Ganzhorn's Mausmaki

| Ganzhorn's Mausmaki | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Microcebus Ganzhorni | ||||||||||||

| Hotaling , Foley , Lawrence , Bocanegra , Blanco , Rasoloarison , Kappeler , Barrett , Yoder , Weisrock , 2016 |

Ganzhorns Mausmaki ( Microcebus Ganzhorni ) is a primate species from the genus of the Mausmakis within the suborder of the lemurs . It is endemic to southeast Madagascar and was first described in 2016 with two other species of lemur .

features

Since the holotype is a tissue sample, the first description does not contain any information on the characteristics of the species. Prague Zoo calls its animals, which were previously identified as gray lemurs , as Ganzhorn lemurs, but without specifying how they were identified. According to the zoo, they have a fine grayish coat, sometimes with a dark vertical stripe, and a bushy tail. Ganzhorn's mouse lemur is one of the larger species of mouse lemur and reaches a body length of 12.5 to 15 centimeters and a tail length of about 13.5 centimeters with a weight of 39 to 90 grams. For a comparative study of supposed populations of the gray mouse lemur, 127 specimens of Ganzhorn's lemurs were measured in the Mandenga Forest between 2000 and 2003 and some measurements were documented. The tail length averaged 13.25 centimeters, the length of the hind feet 3.24 centimeters, length and width of the skull 3.5 and 2.18 centimeters, and the length and width of the ears 2.35 and 1.76 centimeters. The weight of the male specimens varied between an average of 56.6 grams in June and 76.9 grams in December. In the slightly larger female specimens, the weight fluctuated between an average of 64.3 grams in June and 105.6 grams in November. No distinction was made between pregnant and other females.

Way of life

Ganzhorn's lemur, like all lemurs, is nocturnal and mostly hangs out in the trees. It is an omnivore that feeds primarily on fruits and insects. The Prague Zoo names a diet of invertebrates , fruits, flowers and nectar. An outdoor study over four years showed that Ganzhorn's mouse lemur mainly feeds on fruits, with fruits more than 35 millimeters in length being avoided and clearly smaller berries being preferred. Direct observation, seeds in the feces and traces of eating on fruits, the consumption of the fruits of 66 different plant species could be proven. The seeds of the fruits of 34 different species passed through the digestive tract unscathed. Whole-horned lemurs play an important role in the distribution of plant seeds up to a length of 6.5 millimeters in their habitat. While 63 percent of all observed food intake concerned fruit, 22 percent ate flowers, 11 percent arthropods and 4 percent gums . The study yielded very similar results for the two sympatric species of fat-tailed lemur ; the food competition is not reduced by choosing different forage, but by staying at different heights of the treetops: an average of 4 meters for Ganzhorn's mouse lemur, 5 meters for Western fat-tailed lemur and 7 meters in the brown fat-tailed lemur .

Wholehorn lemurs spend the nights looking for food alone and the days alone or in groups in sleeping nests. In contrast to lemurs like the fat-tailed lemur, there is no fixed pair bond. While the female animals remain on an area of about half a hectare, the males roam on up to three hectares. The length of gestation is specified by the Prague Zoo as 54 to 68 days, a litter consists of two or three young. Ganzhorn lemurs have two or three litters within a year. Although litters occur between October and April or May, November is the month with more than half of the litters and January / February the period with more than a quarter of all litters. It is believed that there will be a third litter in April / May.

Ganzhorn lemurs have two strategies that can be used alternatively to react to times of insufficient food supply and unfavorable environmental conditions with reduced energy consumption. An animal hibernated for 30 days. The body temperature followed the ambient temperature and fell to 11.5 ° C. The animal woke up at irregular intervals, and the body temperature rose to the normal level. These waking phases comprised a total of 17.1 percent of the duration of hibernation. A second animal examined only fell repeatedly during the morning hours in phases of torpor , with the torpor lasting an average of about one hour and a maximum of five hours, and occurring on 24 of the 85 days of the investigation. The body temperature did not drop below 27 ° C and normal activity was shown during the nights. Since females hibernate more frequently, the proportion of males among roaming mouse lemurs can be increased at times when large parts of the population are in hibernation. Especially in July and August, the southern winter and the time when there is a lack of fruits and flowers, many animals are in hibernation.

The lifespan is up to 14 years in captivity. This lifespan is far from being reached in freedom. As part of a long-term study, 171 specimens were caught between 2000 and 2003. Only 13 percent of the animals, 16 percent of the females and 9 percent of the males, were recaptured the following year, and only two females and one male in the third year.

Parasites

The parasite fauna of the wild population of Ganzhorn's mouse lemur has been extensively studied. In the period from March 2003 to April 2004, 101 specimens were caught in traps and their faeces examined for endoparasites. In this roundworms ( prevalence 26.7%) strongyles (15.9%), whipworms (8.9%), hairworms (2%) (1%), trichostrongyles, Pfriemenschwänze (16.8%), certain unspecified Nematodes (59.4%), tapeworms (38.7%), flukes (2%), scratchworms (2%) and coccidia (68.3%) were detected. The at least 20 types of gastrointestinal parasites found in Ganzhorn's mouse lemur contrast with four types of nematodes, which the French parasitologist Alain Chabaud and his colleagues were able to name for the gray mouse lemur in 1965. The prevalence of parasite infestation is significantly higher in Ganzhorn's mouse lemur than in the species of brown lemur and western lemur, which also occur in the Mandena Forest. This is attributed to the significantly higher population density of the mouse lemur. As a result of their promiscuity and greater mobility, male lemurs show a greater diversity of their parasite fauna. The transmission of single-host parasites is favored by the social behavior of hosts with close contact in family groups, while multi-host parasites with developmental stages in invertebrate hosts benefit from the fact that lemurs also consume invertebrates. Since some parasites infest both the lemur tied to the Mandena Forest and the house rats living inside and outside the fragments of the forest , the rats are considered to be important vectors that transport parasites between largely isolated populations of lemurs. Since the habitat of Ganzhorn's lemurs is frequently visited by humans, there is concern of the transmission of zoonotic parasites to visitors or human pathogens to the lemurs.

distribution and habitat

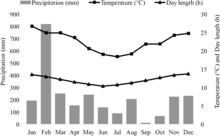

The type location is the Mandena Forest in the Taolanaro district of the Anosy region , about 12 kilometers north of the city of Tolagnaro in southeast Madagascar ( 24 ° 56 ′ 54.2 ″ S , 46 ° 59 ′ 42 ″ E ). The Mandena Forest is an approximately 230 hectare protected area that a directly neighboring Malagasy mining company of the Rio Tinto Group had to set up in 1999 to compensate for interventions in nature through the mining of ilmenite . Nothing is known about the extent of the actual distribution area and the size of the population, but there is no connection with the distribution areas of the gray mouse lemur in western Madagascar. The Madena Forest is located about three kilometers from the coast at 0 to 20 meters above sea level. It consists of evergreen trees ten to fifteen meters high with dense undergrowth that take root in a sandy substrate. Compared to the rainforests in eastern Madagascar, the coastal zone has a less pronounced seasonal change in rainfall. The average temperature is 22.5 ° C and the average annual rainfall is around 1600 mm, with a rainy season from November to April. Around 82 hectares of the protected area are periodically flooded, the remaining 148 hectares consist of fragmented remnants of the coastal forest.

The well-known distribution area of Ganzhorn's Mausmaki is part of a landscape characteristic of the coastal zone in southeast Madagascar, which was continuously forested until the 1950s and has since been affected by strong anthropogenic changes. Large parts of the forests have been cleared for the extraction of construction timber and for the production of charcoal for the nearby regional capital Tolagnaro, for the benefit of human settlement and for mining. Between 1995 and 1998 the extent of environmental degradation increased rapidly and today less than ten percent of the natural forest areas are preserved. These remaining areas are highly fragmented and there is concern that the habitat separation will result in isolated populations without genetic exchange. The immediate vicinity of the fragmented residual forest is occupied by the mining company's premises, monocultures of Eucalyptus robusta and lemon eucalyptus for the production of timber and sandy fallow land exposed to soil erosion with vegetation of heather and ruderal vegetation .

More recent population genetic studies, which focused on the variable MHC complexes , revealed that the population of Ganzhorn's mouse lemurs in the Mandena Forest is comparatively small, but that this species is less affected by a reduction in genetic diversity than other lemurs is. When examining the populations of individual fragments, it was initially possible to establish a relationship between the size of the populations and the size and quality of the fragments. Larger fragments had larger populations and fragments subject to severe anthropogenic changes had lower population densities. The fragmentation of the habitats did not completely prevent the exchange between the populations, but the corridors set up have significantly increased genetic exchange.

The lemur fauna of Madagascar has been intensively researched for decades. The Mandena Forest mouse lemurs have also been the subject of research, including several long-term parasitological and population- biological studies. In the publications based on these studies, Ganzhorn's lemurs are consistently referred to as gray lemurs. Since the gray mouse lemur does not occur in the Mandena Forest, these earlier publications can be safely assigned to Ganzhorn's mouse lemur. In addition to all-horn mouse lemur lives a number of other lemurs in Madena Forest: the kathemeralen types collared brown lemur and southern lesser bamboo lemur and also nocturnal species greater dwarf lemur, fat-tailed dwarf lemur and Southern Woolly Lemur . For the two fat-tailed lemurs it is unclear whether they colonize the swamp area of the Mandena Forest, all other species are also represented there.

Systematics

Ganzhorns Mausmaki is a species of the genus Mausmakis in the family Katzenmakis . Few mouse lemurs had been described by the late 20th century. Since then, numerous species have been separated and in some cases only described based on photos or DNA samples. Ganzhorn's Mausmaki was described together with Microcebus boraha and Microcebus manitatra in 2016 . The genus Microcebus thus contains 24 species.

Initial description

As early as 2009, a research group headed by David W. Weisrock from Duke University, as part of a comprehensive study to delimit the species of Malagasy mouse lemurs, found that the Mandena Forest mouse lemurs form a clade . However, they have not yet been granted a species status. It was not until 2016 that Ganzhorn's Mausmaki and two other clades identified in 2009 were first described by a team led by the American zoologist Scott Hotaling , who also included Weisrock and most of the 2009 authors.

The holotype is a tissue sample that was taken on August 8, 1998 by Jörg Ganzhorn in the Mandena Forest from the ear of an adult male animal that was initially considered to be a gray mouse lemur . The sample has been added to the collection of the Duke Lemur Center at Duke University under the number DLC # 100 . The first description does not contain any measurements or other information on the phenotype . An analysis of the nuclear and mitochondrial DNA confirmed that the Mandena Forest mouse lemurs form a clade. With the help of statistical analyzes, the clade was reliably identified as a species. The definition of a DNA sample as a holotype made here - instead of a preserved specimen - is unusual, but has been repeatedly practiced in recent years for newly described primates if the type specimens were zoo animals or species protection required their release. The International Rules for Zoological Nomenclature allow such a procedure, although it was controversial in the past.

The species name Ganzhorni honors the German biologist and university professor Jörg Ganzhorn from the Zoological Museum of the University of Hamburg , who has been researching the ecology and biodiversity of Madagascar for more than 30 years and who has taken the tissue sample on which the first description is based. The name was given in recognition of his contributions to the knowledge of the mouse lemurs and other lemurs and his efforts to protect them.

Since the first description of Ganzhorn's Mausmaki, the Pilsen Zoo and Prague Zoo have reported keeping this species. Two pairs in Pilsen had previously been identified as gray lemurs.

Hazard and protection

The IUCN has not yet carried out a risk analysis for Ganzhorn's mouse lemur . As species in Appendix I, all lemurs are subject to the trade restrictions of the Washington Convention . Since habitat destruction is the greatest threat to the lemurs of Madagascar, habitat conservation is the most important protective measure.

The Mandena Forest sanctuary serves to protect all lemurs that live there. One of the environmental protection requirements to which the mining company operating in the immediate vicinity is subjected is the establishment of corridors by planting trees with which the fragments of the relic forest are networked. These corridors consist of 20 percent autochthonous species and 80 percent exotic species. They are accepted by Ganzhorn's mouse lemurs within five years of planting, provided they are planted with suitable trees. Mixtures of native trees with the Australian Eucalyptus robusta and corridors with the also exotic Acacia mangium are well received, whereas those with the species Melaleuca quinquenervia , which is invasive in Madagascar , are not. Corridors with dense undergrowth are preferred.

literature

- Scott Hotaling, Mary E. Foley, Nicolette M. Lawrence, Jose Bocanegra, Marina B. Blanco, Rodin Rasoloarison, Peter M. Kappeler , Meredith A. Barrett, Anne D. Yoder, David W. Weisrock. Species discovery and validation in a cryptic radiation of endangered primates: coalescent-based species delimitation in Madagascar's mouse lemurs. In: Molecular Ecology 2016, Volume 25, pp. 2029-2045, doi : 10.1111 / mec.13604 (first description);

- Robert D. Martin : A preliminary field-study of the lesser mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus JF Miller 1777) . In: Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 1972, supplement 9, pp. 43-89 (not viewed);

- Robert D. Martin: A review of the behavior or the lesser mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus, JF Miller 1777) . In: Richard P. Michael and John Hurrell Crook (Eds.): Comparative Ecology and Behavior of Primates . Academic Press, London 1973, ISBN 0-12-493450-1 , pp. 1-68 (not viewed).

Web links

- ScienceDaily (April 15, 2016): Three new primate species discovered in Madagascar

- Ganzhorn's mouse-lemur (Microcebus Ganzhorni) at Zoo Plzen , Video of a mouse lemur identified as a Ganzhorn Mausmaki in the Pilsen Zoo on the website of Joel Sartore

- Ganzhorn's mouse-lemur (Microcebus Ganzhorni) at Zoo Plzen , another video by Joel Sartores on Vimeo

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Maki Ganzhurnov (Microcebus Ganzhorni) , Prague Zoo website , accessed on March 25, 2019.

- ↑ a b c Petra Lahann, Jutta Schmid and Jörg U. Ganzhorn: Geographic Variation in Populations of Microcebus murinus in Madagascar: Resource Seasonality or Bergmann's Rule? In: International Journal of Primatology 2006, Volume 27, No. 4, doi : 10.1007 / s10764-006-9055-y .

- ↑ a b Petra Lahann: Feeding ecology and seed dispersal of sympatric cheirogaleid lemurs (Microcebus murinus, Cheirogaleus medius, Cheirogaleus major) in the littoral rainforest of south-east Madagascar . In: Journal of Zoology 2007, Volume 271, pp. 88-98, doi : 10.1111 / j.1469-7998.2006.00222.x .

- ↑ a b Brigitte M. Raharivololona, Rakotondravao and Jörg U. Ganzhorn: Gastrointestinal parasites of Small Mammals in the Littoral Forest of Mandena . In: Jörg U. Ganzhorn, Steven M. Goodman and Manon Vincelette (Eds.): Biodiversity, Ecology, and Conservation of Littoral Ecosystems in the Region of Tolagnaro (Fort Dauphin), Southeastern Madagascar . Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 2007, ISBN 978-1-893912-00-7 , pp. 247-258.

- ↑ Jutta Schmid and Jörg U. Ganzhorn: Optional strategies for reduced metabolism in gray mouse lemurs . In: Naturwissenschaften 2009, Volume 96, pp. 737-741, doi : 10.1007 / s00114-009-0523-z .

- ^ A b Jean-Baptiste Ramanamanjato and Jörg U. Ganzhorn: Effects of forest fragmentation, introduced Rattus rattus and the role of exotic tree plantations and secondary vegetation for the conservation of an endemic rodent and a small lemur in littoral forests of southeastern Madagascar . In: Animal Conservation 2001, Volume 4, pp. 175-183, doi : 10.1017 / S1367943001001202 .

- ↑ Alain G. Chabaud , Edouard-R. Brygoo and Annie-J. Petter : Les nématodes parasites de lémuriens malgaches. VII. Description of six espèces nouvelles et conclusions générales . In: Annales de Parasitologie 1965, Volume 40, No. 2, pp. 181-214, digitized .

- ↑ a b Brigitte M. Raharivololona: Gastrointestinal parasites of Cheirogaleus spp. and Microcebus murinus in the littoral forest of Mandena, Madagascar . In: Lemur News. The Newsletter of the Madagascar Section of the IUCN / SSC Primate Specialist Group June 2006, No. 11, pp. 31-35, digitized .

- ↑ a b c d e Scott Hotaling et al .: Species discovery and validation in a cryptic radiation of endangered primates: coalescent-based species delimitation in Madagascar's mouse lemurs. In: Molecular Ecology 2016, Volume 25, pp. 2029-2045, doi : 10.1111 / mec.13604 .

- ↑ a b c d e Timothy M. Eppley et al .: Ecological Flexibility as Measured by the Use of Pioneer and Exotic Plants by Two Lemurids: Eulemur collaris and Hapalemur meridionalis . In: International Journal of Primatology 2017, Volume 38, No. 2, pp. 338-357, doi : 10.1007 / s10764-016-9943-8 .

- ↑ a b c B. Karina Montero: Challenges of next ‐ generation sequencing in conservation management: Insights from long ‐ term monitoring of corridor effects on the genetic diversity of mouse lemurs in a fragmented landscape . In: Evolutionary Applications 2019, Volume 12, pp. 425-442, doi : 10.1111 / eva.12723 .

- ↑ Jörg U. Ganzhorn et al .: Population Genetics, Parasitism, and Long-Term Population Dynamics of Microcebus murinus in Littoral Forest Fragments of South-Eastern Madagascar . In: Judith Masters, Marco Gamba and Fabien Génin (eds.): Leaping Ahead. Advances in Prosimian Biology . Springer Science + Business Media, New York 2013, ISBN 978-1-4614-4510-4 , pp. 61-69.

- ↑ Peter M. Kappeler et al .: Long-term field studies of lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers . In: Journal of Mammalogy 2017, Volume 98, No. 3, pp. 661-669, doi : 10.1093 / jmammal / gyx013 .

- ↑ Casey M. Setash et al .: A biogeographical perspective on the variation in mouse lemur density throughout Madagascar . In: Mammal Review 2017, Volume 47, pp. 212-229, doi : 10.1111 / mam.12093 .

- ^ Giuseppe Donati et al .: Lemurs in Mangroves and Other Flooded Habitats . In: Katarzyna Nowak, Adrian A. Barnett, Ikki Matsuda (eds.): Primates in Flooded Habitats . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2019, pp. 29-32, doi : 10.1017 / 9781316466780.006 .

- ↑ David W. Weisrock et al .: Delimiting Species without Nuclear Monophyly in Madagascar's Mouse Lemurs . In: PLoS ONE 2010, Volume 5, No. 3, Article e9883, doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0009883 .

- ^ Frank-Thorsten Krell and Stephen A. Marshall: New Species Described From Photographs: Yes? No? Sometimes? A Fierce Debate and a New Declaration of the ICZN . In: Insect Systematics and Diversity 2017, Volume 1, No. 1, pp. 3-19, doi : 10.1093 / isd / ixx004 .

- ↑ Birgit Kruse: Microcebus Ganzhorni: New species of monkey named after biologists at the University of Hamburg. University of Hamburg, press release from April 15, 2016 from Informationsdienst Wissenschaft (idw-online.de), accessed on April 15, 2016.

- ↑ Anonymous: Seznam zvířat chovaných v zoo a bz města Plzně v roce 2017. Census of animals kept in Pilsen zoo by the end of 2017 year , p. 3. In: Zoo Pilsen (ed.): Zoologická a botanická zahrada města Plzně / výroční zpráva. Zoological and Botanical Garden Pilsen / Annual Report 2017 , digitized version , accessed on March 25, 2019.

- ↑ Appendices I, II and III valid from 4 October 2017 , website of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora , accessed on March 26, 2019.

- ↑ Laza Andriamandimbiarisoa et al .: Habitat corridor utilization by the gray mouse lemur, Microcebus murinus, in the littoral forest fragments of southeastern Madagascar . In: Madagascar Conservation & Development 2015, Volume 10, No. 3, pp. 144–150, doi : 10.4314 / mcd.v10i3.7 .