Bell cemetery

Glockenfriedhof is the name of a place for bells , where church bells , town hall bells and the like during the First and Second World War . were collected in the course of so-called "bell deliveries". Because of their bronze, bells were an essential material for the war effort and were drawn in during the First and Second World Wars, first voluntarily, then forcibly, in order to be melted down and used in the armaments industry . The bells were sent to industrial processing from the collection points. In Germany they were part of the so-called metal donation of the German people .

First World War

Austria

Voluntary bell action

In May 1915 an action started for the voluntary disposal of church bells, only bells from the 19th and 20th centuries were free to be melted down. These were used up by May 1917.

1st bell action 1916/17

The norm for the first compulsory levy was that two thirds of the total weight of the bells in each parish had to be removed. The proceeds were to be used as a bell fund and used to purchase new bells of the same quality after the First World War. The delivery of the bells was thus interpreted as a "loan" to the fatherland in difficult times. After the return of orderly conditions, every parish should be able to renew or even enlarge the bells. It was also agreed that the bells must not be thrown down from the tower and must be delivered in their entirety.

The first "bell action" was carried out from September 27, 1916 to May 25, 1917. The bells were weighed and documented at the assembly points. The proceeds for the delivered bells had to be invested in the fifth war loan , which became worthless due to the post-war inflation.

2nd bell campaign 1917/18

No sooner had the last bells from the first bell action been removed than the Reichsgesetzblatt No. 227 announced that all bells with a diameter of more than 25 cm were to be claimed. Bells of particular artistic or historical value were excluded. Of the bells cast in the 17th and 18th centuries, only those with special figural or ornamental decorations or with historically significant inscriptions should be preserved. Only a few exemplary objects should be spared from the bells from the 19th century.

At the urgent request of the episcopal ordinariate, the War Ministry approved on June 11, 1917 that at least the smallest bell should remain in each church. The second bell action was carried out from November 20, 1917 to April 12, 1918. The proceeds had to be invested in the VII. And VIII. War Loan.

The bells were categorized in bell cards in order to be able to put valuable bells under protection, whereby only bells from the time before 1600 remained protected. Protected bells were also marked in red to avoid accidental acceptance. Bells made of "copper or copper alloys (bronze, brass, gunmetal, etc.)" were divided into four categories:

- 1st category: bells made of copper or copper alloys with an outer diameter of less than 25 cm are not used for war purposes.

- 2. Category: Bells for signaling purposes on railways and ships are not used for war purposes.

- 3rd category: Bells with special artistic or historical value, for the determination of which the organs of the State Monuments Office are appointed, will not be used for war purposes. In case of doubt, the Ministry of Culture and Education decides. The decision will be communicated to the responsible military command.

- 4th category: Bells that do not belong to churches and chapels must be reported by the owner to the local military command with precise details of the address by 6 June 1917 at the latest and may not be sold or processed by the owner. Four weeks after the announcement of this ordinance of May 22, 1917, the owner can sell the bells to the responsible military command, or the military command is entitled to withdraw the bells that have been used or, if necessary, to remove them.

Effects

In Upper Austria , 1137 bells with a weight of almost 553 tons were delivered in the first bell action and 561 bells with over 182 tons in the second bell action, so a total of 1698 bells with 735 tons of metal. The largest deliverers in terms of weight were Mondsee Abbey (4,364 kg), Schlägl Abbey (3,030 kg), the old cathedral in Linz (2937 kg) and the parish church of Steyr (2906 kg). In Upper Austria, the bells in St. Florian Monastery , in the New Cathedral in Linz and in the parish church of Schärding were completely spared . Valuable old bells have also been preserved in the parish church of Mauthausen and the parish church of Freistadt . The St. Florian bell foundry was founded as early as 1917 to meet the need for new bells after the end of the war.

Germany

German bells (and only those made of bronze) were removed and temporarily stored in bell cemeteries. The bells were divided into three groups:

- Group A: Bells for which deferral or exemption according to groups B or C was not an option.

- Group B

- Bells with only moderate scientific, historical or artistic value or if no final assessment has yet been made for bells to be classified in group C (keyword “art value”).

- Bells that were required to ring without the reason for exemption 1) or 3) being able to be asserted (to be reported with the password “bell”). In this case, only the lightest bronze bell was temporarily put on hold.

- Bells for which compensation would have been paid below the pure installation costs of replacement bells ( excluding the costs for the replacement bell itself) (keyword “high installation costs”).

- Group C: Bells of particular scientific, historical or artistic value (if certified by the competent expert). Before the report was available, the bells were to be classified in group B.

Compensation ("takeover price") was paid for bells to be delivered

- for bells over 665 kg 2 marks per kg plus 1,000 marks basic fee

- for bells under 665 kg 3.50 marks per kg (without additional basic fee).

It is estimated that around 65,000 bells were melted down during the First World War. The bells from before 1860 (group B and C) were spared. A publication from 1954 speaks of 21,000 tons of bells that had to be handed in - this corresponds to a number of around 60,000 to 70,000 bells (the loss in Thuringia is said to have been 3,000 to 4,000 bells).

In order to promote the culture of remembrance , the German Folklore Society called in 1917 to collect “bell sayings, bell sagas and bell customs”, which was only carried out on a larger scale in the Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin . Otherwise, the senders were often content with describing the bells and their acceptance. After the end of the war there were 365 bells that had escaped meltdown but had not been inventoried either at the Berlin Metal Mobilization Office . Therefore, a list with detailed descriptions for identifying the bells was printed out, which was successful in at least 250 cases.

Second World War

Change of raw material supply

The Reich Office for Metals in Berlin, an executive body of the Reich Ministry of Economics , controlled the allocation of raw materials and the use of products. After the outbreak of the war, the ore and raw metal deliveries from overseas that were lost at the Norddeutsche Affinerie were replaced by deliveries from Norway , Finland , Yugoslavia and Turkey . In addition, from 1940 onwards, the Reichsstelle für Metle supplied metals from metal donations by the German people , requisitioned church bells from Germany and the occupied territories, bronze monuments and scrap metal to the smelting works .

Requirement of the bells

The NS administration classified the bells into types A, B, C and D. Types C and D represented historically valuable bells. While A and B had to be surrendered immediately, type C was in "waiting position", whereas type D was protected. Some mayors also had the historically valuable bell (type D) removed from the tower for the “ final victory ”. Only one bell was allowed per church, usually the lightest. Bells from the 16th and 17th centuries and from the Middle Ages were not generally spared. Steel bells were not drawn in.

In the Netherlands , from late 1942 to early 1943, bells were confiscated, roped down from the church towers, collected in interim storage facilities and then transported to Germany by ship.

Melting down the bells

It is estimated that around 45,000 bells in Germany fell victim to the death of bells ordered by the Nazi leadership during the Second World War (in the area of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Thuringia there were exactly 2,584 bells). In addition, another 35,000 were melted down in the occupied territories.

The bells went mainly to the Hüttenwerke Norddeutsche Affinerie and Zinnwerke Wilhelmsburg, both in Hamburg. From 1941 onwards, church bells of the A, B, and C categories were mainly delivered to the North German Affinerie by railroad cars. A bells were processed immediately, B and C bells put back. The determined value had to be paid immediately to the Reich Office for Metals. First, an existing converter was installed , and from July 1942 two converters were installed in the north-western annex of the copper refinery.

Bell cemeteries

“After they were removed from the towers, the bells were collected and taken to the iron and steel works by the district craftsmen in shiploads and freight trains. Because of the favorable and at that time still undisturbed transport connections, the two smelting works in Hamburg received the vast majority of all bells. The other German copper smelters in Oranienburg, Hettstedt, Ilsenburg, Kall and Lünen were less involved in the scrapping. "

Bell cemetery in Hamburg-Veddel

The bell cemetery in Hamburg-Veddel (also known as the bell cemetery ) was a large area, the former timber warehouse on Reiherstieg , near the port of Hamburg , which was used for the temporary storage of church bells from all over the German Empire and the territories occupied at the time. Due to lack of space, the bells were stacked in a pyramid shape and were damaged by this and by the bombing .

Between 1939 and 1945, numerous bells and bronze monuments, some of them famous, were melted down at the North German Affinerie and were thus lost forever. A total of around 90,000 bells were brought to Hamburg, of which around 75,000 were melted down.

In the bell cemetery in Hamburg-Veddel alone , well over 10,000 bells were waiting for the furnace at the end of the war.

Bell cemetery at the Kaiserkai in Hamburg

The photographer Heinrich Hamann photographed after the war the devastation in Port of Hamburg during the Second World War. These images are kept in the archive of the International Maritime Museum (taken from the Hamburg Archive Fuchs). A picture shows the Kaiserkai as a bell camp between Sandtorhafen and Shed 10.

More bell cemeteries

There were bell cemeteries in particular near ironworks. At the end of the war, bells were stored next to the location in Veddel at the following collection points:

- Hamburg-Harburg

- Oranienburg , 300 bells

- Hettstedt , Mansfelder Kupferschieferbergbau AG, 400 bells

- Ilsenburg , 600 bells

- Lünen , Hüttenwerke Kayser AG, 2000 bells

- Vienna - The bells were transported from the Vienna Bell Cemetery to Hamburg

Return of preserved bells

After the bells were confiscated across Germany, tens of thousands of bells came together in the smelter's warehouse and in the bell cemeteries. There they were stacked two or more times on top of each other due to lack of space. The consequences of many bells returned after the end of the war often only became apparent after they have rung for a long time: the finest hairline cracks invisible to the eye led to them bursting.

The bells that remained in the bell cemeteries after the end of the war (not yet melted down) were put aside if possible, but this was not always possible due to the lack of attribution.

Friedrich Wilhelm Schilling (1914–1971) worked after the Second World War as custodian of the Hamburg bell collection center and, like his uncle Franz August Schilling, worked in Apolda to return the bells. He ensured the return home of more than 13,000 bells that were stored in the Hamburg free port and had been spared from melting down.

After elaborate identification measures, some of which took years, by representatives of the church and the protection of monuments in the bell office, the later committee for the return of bells (ARG), most of these bells were returned to their home communities. Bells from the former German, but now Polish or Soviet eastern regions, could not be returned due to the political situation; Bells from there were therefore given to West German parishes as sponsored bells.

When the bells were returned to Belgium and Poland , bells were stolen in the port of Hamburg due to the high metal prices. Bells also disappeared in Lünen.

Documentation of the bells

There is a bell archive of the Committee for the Return of Bells (ARG), which is kept in the Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg . The bells in Germany, as far as possible those that have worn off, are registered in a bell atlas and photographed. Files of the committee for the return of church bells are in the Evangelisches Zentralarchiv Berlin, inventory 52.

literature

- Simon Klampfl: The "Patriotic War Metal Collection " (1915) of the Austrian Museum of Applied Arts. Thesis. University of Applied Arts, Vienna 2008.

- Fortunat Schubert-Soldern : XVIII. Metal confiscation in Austria . In: Paul Clemen (ed.): Art protection in war. Reports on the condition of the art monuments in various theaters of war, 2 volumes, Leipzig 1919 (volume 2), pp. 215–221.

- Florian Oberchristl: Bell customer of the Diocese of Linz. Verlag R. Pirngruber, Linz 1941, 784 pages.

- Rainer Vogel: The military requisition of the bells in the deaneries Freudenthal / Bruntál o. Bruntál, Jägerndorf / Krnov o. Bruntál and Troppau / Opava o. Opava in 1917 in Austria - Silesia and Silesia . Munich 2009, digitized .

Web links

- Got away again. Homecoming from the bell cemetery In: “Der Spiegel” 15/1947. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Fortunat Schubert-Soldern: XVIII. Metal confiscation in Austria. In: Paul Clemen (ed.): Art protection in war. Leipzig 1919, p. 219f.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Oberchristl 1941, p. 14.

- ↑ 227. Ordinance of the Ministry of National Defense in agreement with the ministries involved and in agreement with the Ministry of War of May 22, 1917, regarding the use of bells for war purposes. In: Reichsgesetzblatt for the kingdoms and states represented in the Reichsrat , year 1917, p. 586, digitized [1] .

- ↑ Legal basis for the military requisition in the kk monarchy. Quoted from Rainer Vogel: The military requisition of bells in the dean's offices Freudenthal / Bruntál o. Bruntál, Jägerndorf / Krnov o. Bruntál and Troppau / Opava o. Opava in 1917 in Austria - Silesia and Silesia. Munich 2009, p. 4f and footnotes.

- ↑ a b Oberchristl 1941, p. 719.

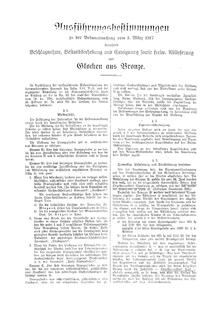

- ^ Saarlouis district committee (ed.): Implementing provisions for the announcement of March 1, 1917 regarding confiscation, inventory and expropriation as well as voluntary Delivery of bells made of bronze . Saarlouis March 17, 1917.

- ↑ a b c d e W. Finke: The tragedy of the German church bells. In: Silesian Mountain Rescue. SB57 / N32 / S570, 1957.

- ^ Fritz Schilling (Superintendent in Sonneberg-Oberlind ) / Evangelical Lutheran Church in Thuringia , regional church council (ed.): Our bells - Thuringian bell book. Gift of the Thuringian Church to the Thuringian people. Dedicated to the "Thuringian master bell founder Dipl.-Ing. Franz Schilling in Apolda in gratitude for his work for the good of our communities ”. Jena 1954, p. 45.

- ↑ Franziska Dunkel: “Sounds of lack.” In: Fastnacht der Hölle. The First World War and the senses. House of History Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart 2014, pp. 136–139.

- ^ Glockenfriedhof, (source HWE). In: Franklin Kopitzsch , Daniel Tilgner (Ed.): Hamburg Lexikon. 2nd, revised edition. Zeiseverlag, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-9805687-9-2 , p. 178.

- ↑ a b The North German Affinerie during the Second World War. In: Norddeutsche Affinerie (Ed.): 100 years of Norddeutsche Affinerie. Hamburg in April 1966, pp. 73-76.

- ^ Johann Werfring: The dreary time of the bell cemeteries. In: “Wiener Zeitung” of June 6, 2012, supplement “Program Points”, p. 7. Accessed on June 12, 2012 .

- ↑ See St. Gertrud (Hamburg-Uhlenhorst) #Tower, clock and bells

- ↑ Pictures of the bell robbery in the Netherlands on the NIOD website

- ^ Fritz Schilling / Evangelical Lutheran Church in Thuringia , Regional Church Council (ed.): Our bells - Thuringian bell book. Gift of the Thuringian Church to the Thuringian people. Jena 1954, p. 45.

- ↑ Bell cemetery. (Source HWE). In: Franklin Kopitzsch, Daniel Tilgner (Ed.): Hamburg Lexikon. 2nd, revised edition. Zeiseverlag, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-9805687-9-2 , p. 178.

- ↑ Cannon fodder. Why times of war were bad times for bells too ( memento of the original from March 26, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (Article on philippuskirche.de). Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ↑ Got away again. Homecoming from the bell cemetery In: “Der Spiegel” 15/1947. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ Franz-Josef Krause: At Pentecost they will be rung ( memento from June 26, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ). In: Hamburger Wochenblatt Fuhlsbüttel from May 25, 2012.

- ↑ Friedel Stratjel and Dieter Friedl: Heimatbuch der Marktgemeinde Bernhardsthal including the sister communities Reinthal and Katzelsdorf as well as the neighboring community Rabensburg (= Internet version of the printed Heimatbuch der Marktgemeinde Bernhardsthal by Robert Franz Zelesnik from 1976), Bernhardsthal 2009-12, p. 82 ( PDF; 3.6 MB).

- ↑ Franz Peter Schilling: Erfurt bells - the bells of the cathedral, the Severikirche and the Peterskloster zu Erfurt. (also double issue 72–73 of the series The Christian Monument ). Berlin 1968, p. 56.

- ↑ Bell cemetery. (Source HWE). In: Franklin Kopitzsch, Daniel Tilgner (Ed.): Hamburg Lexikon. 2nd, revised edition. Zeiseverlag, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-9805687-9-2 , p. 178.

- ^ The destroyed bells In: Museumsverein Meersburg (Hrsg.): Meersburger traces. Verlag Robert Gessler, Friedrichshafen, 2007. ISBN 978-3-86136-124-4 , pp. 105-108.

- ↑ German Bell Atlas . [Arr. by Sigrid Thurm]. Lim. by Günther Grundmann. Continued by Franz Dambeck. Edited by Bernhard Bischoff u. Tilmann Breuer. Verlag Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin.

- ^ German dioceses, Advisory Committee for the German Bell System 2008: Recommendations for the inventory of bells

- ↑ LkAH N 048. discount Christian Mahrenholz . In: Arcinsys Lower Saxony . Retrieved December 21, 2017 .