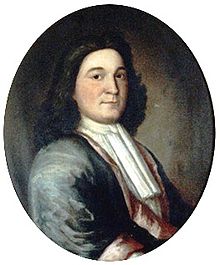

Joseph Dudley

Joseph Dudley (born September 23, 1647 in Roxbury , Massachusetts Bay Colony , † April 2, 1720 in Roxbury, Province of Massachusetts Bay ) was an English colonial administrator in New England . He was the son of one of the founders of his native city and led the Dominion of New England for a few months as Council President in 1686, which was overthrown as part of the uprising in Boston in 1689 . He later served on the Province of New York Council. In New York he presided over the court proceedings in which Jacob Leisler and the Leisler's Rebellion , which he initiated and named after him, were heard . He was Lieutenant Governor of the Isle of Wight for eight years in the 1690s and Member of the British Parliament for one year at the beginning of the 18th century . In 1702 he was appointed governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay and the Province of New Hampshire at the same time , and held these offices until 1715.

His term in Massachusetts was fraught with tension and hostility as his political opponents boycotted his efforts to earn a steady income and regularly complained about his official behavior and personal life. During this time, the Queen Anne's War also fell , in which the Dominion was at war with New France and suffered from constant attacks from the French and Indians . Dudley made an unsuccessful attempt to conquer the Acadian capital Port Royal in 1707 , but was able to successfully carry out another attempt at conquest in 1710 . In 1711 he led an unsuccessful attack on Quebec City .

During Dudley's term of office, hostile patterns of behavior among the population against the royal administration of Massachusetts developed, which were regularly sparked by the payment of colonial officials. This hostility was directed against most of the governors of Massachusetts until the American War of Independence ; his tenure in New Hampshire, however, was comparatively undisputed.

Early life and first political experiences

Joseph Dudley was born on September 23, 1647 in Roxbury , Massachusetts Bay Colony . His parents were Katherine Deighton Hackburne Dudley and Thomas Dudley , one of the founders and leaders of the colony. His father was 70 when he was born, so he was raised by his mother and stepfather, John Allin, whom she married after Thomas Dudley's death in 1653.

He graduated from Harvard College in 1665 and was declared a Freeman in 1672 . From 1673 he represented Roxbury as a member of the Massachusetts General Court and was elected to the Colonial Council in 1676. With the outbreak of King Philip's War in 1675, Dudley accompanied the colonial troops in the battle against the Indians and was involved, among other things, in the so-called Great Swamp Fight , in which the Narraganset were beaten back to decide the war. He served for several years as a commissioner for the New England Confederation and was posted on various diplomatic missions to neighboring Indian tribes. As a diplomat he negotiated the border between Massachusetts and the neighboring Plymouth Colony as part of a larger committee .

Massachusetts

Repeal of the colonial charter

The colonial administration, which had already come increasingly into the focus of Charles II in the early 1660s , was under serious pressure in the late 1670s. Edward Randolph, who was sent to New England in 1676 to collect taxes and enforce navigational files, documented a number of incidents and problems and presented them to the Board of Trade in London.

Colonies' leaders were divided on how to respond to this threat. Dudley, like his brother-in-law Simon Bradstreet and William Stoughton, belonged to a moderate faction that wanted to respond to the king's demands. Opposed to them were the hardliners, who fundamentally refused to allow the Crown to interfere in colonial affairs. While the richer landowners supported the moderate side, the official representatives were more in agreement with the hardliners.

In 1677 Dudley was elected a member of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts .

In 1682 Dudley was sent to London with John Richards to represent Massachusetts to the Board of Trade. Dudley carried a letter of recommendation written by Plymouth Governor Thomas Hinckley , addressed to Colonial Secretary William Blathwayt . With this he was able to build a good relationship, which later contributed a lot to his success as a colonial administrator. At the same time, however, it sparked rumors within the colony about his motives and his ability to effectively advance the interests of Massachusetts. The powers of the two envoys were limited, however, so the Board of Trade insisted on the colonial administration to authorize Richards and Dudley to negotiate modifications to the colonial charter.

The colony dominated by the hardliners, however, rejected this request, which immediately led to a court order ( English quo-warranto- writ ) to return the colonial charter. When Dudley brought this news to Boston in late 1683, a heated debate began in the legislature, in which the hardliners, including the influential pastor Increase Mather , were able to prevail again. In particular, they branded the moderates like Dudley and Bradstreet as "enemies of the colony". Richards sided with the hardliners so that aggression was focused on Dudley, which in the end led to his being removed from office after the 1684 Colonial Council elections.

There were also allegations against him that while in London he had secretly planned to have the charter annulled for personal gain. Dudley had discussed a replacement government with Edward Randolph following the issue of the court order, which was seen as evidence of his hostility to the current leadership of the colony and his work contrary to his mandate as the colony's representative. Randolph, based on the conversations he had with him, decided that losing Dudley in the elections would make him a good servant of the Crown. This in turn gave rise to rumors that Dudley would be appointed governor and Randolph would be his deputy.

In 1684 the Massachusetts Charter was invalidated and the Board of Trade was working on plans to unite all of the colonies in New England into a single province called the Dominion of New England . That process was not yet complete when James II ascended the English throne in 1685 . However, there were difficulties in filling the commission for Edmund Andros , who were to be the governor , so that Randolph had to make a proposal for an interim solution. He recommended Dudley for the post, and so on October 8, 1685, he was installed as President of the Council of New England. The territories covered by his powers included Massachusetts, New Hampshire , Maine, and the Narragansett Country , which is now in southern Rhode Island . Randolph received a variety of subordinate posts, including that of Colonial Secretary, which gave him some power in the colony.

President of the Council in New England

Randolph brought the charter making Dudley the new council president to Boston on May 14, 1686, and Dudley officially assumed office on May 25. However, his reign began unsuccessfully, as some officials appointed to his advisory group refused to take up their work. In addition, he could not reconcile himself with Increase Mather, who refused to accept Dudley's offers to talk. Elections for colonial military officers were also affected as many of them refused to serve. Dudley therefore had to carry out compulsory appointments in which he preferred the politically moderates who had agreed to the king's wishes in the struggle for the old charter. He renewed the treaties with the Indian tribes in northern New England and traveled to Narragansett Country in June 1686 to formally take office.

Dudley's work was severely hampered by his inability to increase state revenue because his mandate did not allow him to pass new tax laws and the old Massachusetts government had annulled all related laws in 1683 pending the loss of the charter. In addition, many citizens refused to pay the few remaining taxes on the grounds that they had been introduced by the old government and were therefore invalid.

Dudley and Randolph also tried to establish the Church of England in the colony, but this largely failed due to a lack of funding. However, they enforced the navigation files, although they did not introduce them to the letter. Since they recognized that some provisions were unfair, for example because they meant paying taxes multiple times on the same case, certain violations of the new laws were not penalized. They recommended that the Board of Trade amend the laws accordingly to reflect reality. Still, the Massachusetts economy was noticeably affected by the implementation of the new laws. Dudley and Randolph eventually fell out over questions of commerce, administration, and religion; Randolph wrote, "I'm being treated worse by Mr. Dudley than Mr. Danforth, " comparing Dudley unfavorably to one of the hardliners.

During Dudley's tenure, based on a petition from Dudley's council, the Board of Trade decided to incorporate the colonies of Rhode Island and Connecticut into the Dominion. Edmund Andros, whose letter of appointment was issued in June, received an appendix to his power of attorney authorizing him to integrate these areas.

Activities under Governor Andros

With his arrival in December 1686, Edmund Andros immediately took over the official business. Dudley was part of his advisory board, judge on the superior court and censor of the press. He was also a member of the committee that worked on harmonizing legislation in the Dominion in order to standardize the previously different regulations of the former individual colonies.

Although the Andros advisory board was supposed to represent all of the Dominion areas, the long distances and the associated travel problems combined with the lack of travel expense reimbursements by the government meant that the council was dominated by representatives from Boston and Plymouth. Dudley and Randolph were widely viewed as central to the "tyranny" of Andros' government. For example, Dudley was constantly harshly criticized and complained about his position as a judge, particularly when he enforced unpopular laws on taxes, community meetings, and land ownership that Andros had passed.

When the first news of the Glorious Revolution reached Massachusetts in 1688 , Andros' opponents saw themselves confirmed. Eventually he was arrested during a riot in Boston in 1689 . Dudley, who was out of town at the time, was also jailed on his return. Being ill, he was released into house arrest on payment of £ 1,000 (around £ 200,000 today) ; shortly afterwards, a mob stormed his home and took him back to prison. There he stayed - partly for his own safety - for ten months and was then ordered by Wilhelm III. Sent back to England with Andros and other former senior Dominion officials. The new colonial leadership formulated charges against Andros and Dudley, but no colonial representative in London wanted to bring them to court. As a result, both men were eventually acquitted and released from custody. Dudley had already worked independently on a defense against the charges, which the Board of Trade viewed as a demonstration of his will and ability to implement the political decisions of the British Crown.

After these operations were completed, Dudley was stranded in London and had few relationships there. So he turned to William Blathwayt for assistance. At the same time he asked his business partner Daniel Coxe about a new job. Coxe was one of the owners of West Jersey and wanted to appoint Dudley there as lieutenant governor. Eventually Dudley was recommended as chairman of the council for New York Governor Henry Sloughter , and accepted the position in 1691.

In addition to his duties on the council, he negotiated with the Indians living in New York and was presiding judge in the trial of Jakob Leisler , who overthrew Andros' lieutenant governor Francis Nicholson in the Leisler's Rebellion named after him in 1689 . The trial was controversial and his role earned Dudley many enemies. Leisler was found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death. Sloughter was initially against an immediate execution of Leisler and his son-in-law Jacob Milborne and preferred to leave the decision to the king. However, under pressure from the opponents of Leisler in his council, he changed his mind, so that both men were executed on May 16, 1691. Cotton Mather claimed that Dudley had a significant influence on the speed with which the execution was carried out, but this was denied by Councilor Nicholas Bayard , who was also an opponent of Leisler.

Dudley left New York in 1692 and returned to Roxbury, where he resumed his old relationships with political friends such as William Stoughton , who had recently been appointed lieutenant governor under Sir William Phips of the newly chartered Province of Massachusetts Bay .

England

Dudley returned to England in 1693 and began a series of intrigues to get a job in New England again. He made himself particularly popular with the religious London political establishment by officially joining the Church of England . With John Cutts he won a personal sponsor who enforced his appointment as Lieutenant Governor of the Isle of Wight , where Cutts himself was Governor. Dudley and Cutts helped each other politically, with Cutts representing Dudley's interests in London and Dudley, in turn, those of Cutts on the island. So much so that Dudley falsified the Isle of Wight general election so that the candidates chosen by Cutts would win the election. This made Cutts extremely unpopular on the island, but was able to continue his tenure until his death in 1707. Dudley also tried to help Cutts with certain financial problems, but failed in an attempt to obtain the right to mint coins in the colonies through an intrigue from Cutts' father-in-law .

The main aim of Dudley's intrigues, however, was the removal of William Phips as governor of Massachusetts, which he did not keep secret from the colonial representatives in London. Unpopular in Massachusetts, Phips was recalled to England to respond to a series of accusations made by his political opponents. Dudley ensured that Phips was arrested shortly after his arrival by presenting exaggerated accusations that Phips had withheld customs revenue from the Crown. Phips died in February 1695 before the indictment could be read against him, and Dudley was optimistic that he would be appointed the next governor.

At this point, however, his enemies in New York and Massachusetts united to prevent this from happening. Jakob Leisler's son was in London and tried to have the expropriation of his father's property withdrawn. With the support of Constantine Phips, who represented Massachusetts in London, a corresponding motion was brought to the British Parliament. In the debate, the trial of Jakob Leisler was also re-examined, and Dudley was summoned to explain and defend his role in it. Afterwards Phips wrote to Cotton Mather : "[Dudley] is more likely not under discussion as governor." Lord Bellomont was finally appointed as successor to William Phips .

Unimpressed, Cutts continued to stand up for Dudley and made sure that he was elected a member of the House of Commons in 1701 , where he represented the Newtown district. This position enabled him to further develop his political ties in London. He managed, at least temporarily, to settle his differences with Constantine Phips and Cotton Mather, and after Bellomont's death in 1701 began running for the office of governor of Massachusetts. This time he was successful and was made governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire by Queen Anne on April 1, 1702 .

Return to New England

Massachusetts and New Hampshire Governor

Dudley's tenure as governor lasted until 1715 and was - especially at the beginning - characterized by regular arguments with the Massachusetts General Court . Dudley had been mandated to set up a regular income for the post of governor, but - like all his successors - could not get this through in the provincial legislature, so that it became a continual issue between the representatives of the crown on one side and those of the colony on the other hand was.

Dudley addressed his complaints in the form of letters to London complaining about men who "love neither the Crown nor the Government of England". In another letter to his son Paul, who was the provincial attorney general at the time , he wrote: "This land is not worth lawyers and gentlemen living in it until its charter is annulled." This letter became public and led to the strengthening of his opponents.

Dudley also angered the powerful Mather family with the appointment of John Leverett as President of Harvard University in place of Cotton Mather . His growing unpopularity also contributed to the fact that he consistently vetoed the elections of advisors and spokesmen for the General Court, which had turned against him in 1689.

In contrast, he was extremely popular in New Hampshire; the local legislature supported him with the queen after the complaints of his political opponents in Massachusetts became known.

Queen Anne's War

During the Queen Anne's War , Dudley was in charge of colonial defense. In June 1703 he tried to forestall Indian hostilities by meeting at Casco Bay , but the French had already strongly influenced the Indians in their favor and incited them against the English, which was finally achieved in August 1703 due to Indian raids on English settlements in the southern Maine led to the outbreak of war. Dudley raised militias and with their help fortified the borders of Massachusetts and New Hampshire from the Connecticut River to southern Maine. The French attacked the English settlement of Deerfield together with the Indians in February 1704 , which went down in history as the Deerfield massacre and caused the population to call for retaliation. Dudley then hired the ranger Benjamin Church to retaliate against Acadian settlements. At the same time, he negotiated in a long process with the French about the release of prisoners from Deerfield, who only wanted to accept this as part of a more extensive agreement.

Primarily because Dudley refused to seek Church permission to attack the Acadian capital, Port Royal , he was viewed by Boston merchants and the Mather family as a sympathizer of smugglers and traders who did illegal business with the French. He tried to counteract this criticism by ordering an attack by the militias on the city in 1707 , which ended unsuccessfully. In 1708 a pamphlet was published in London with the title “ The Deplorable State of New England by reason of a Covetous and Treacherous Governor and Pusillanimous Counselors ” (German: “The deplorable state of New England due to a greedy and insidious governor and despondent advisers”), which confronted his government with serious allegations and was part of an unsuccessful campaign to recall him to England.

In 1709 Dudley again set up militias for a planned campaign against Quebec, but the support troops expected from England were not sent. In 1710, British reinforcements finally reached the province, and together with the militia they attacked Port Royal again , which led to the fall of the city and the establishment of the Province of Nova Scotia . In 1711 the attack on Quebec was reorganized from Boston . The British troops united with the provincial armed forces failed, however, already on the journey due to a serious ship accident on the St. Lawrence River on August 22, 1711, in which seven transport ships and one supply ship capsized. During the war, Dudley also authorized attacks against the Abenaki in northern New England, which, however, remained largely without noticeable effects. After the fall of Port Royal, the number of fighting fell sharply and with the Peace of Utrecht the war ended in 1713.

In the same year Dudley negotiated a separate peace with the Abenaki in Portsmouth . With the aim of separating at least the western Kennebec tribe from the influence of the French, he pursued a tough line in the negotiations and threatened, among other things, to stop trading in goods essential to the survival of the Indians. Although the Treaty of Portsmouth, which was concluded in the end, established the sovereignty of the British over the Abenaki, there are indications that the resulting consequences were not explained to the Abenaki negotiators and that these territorial claims of the British had explicitly rejected in the negotiations. Dudley noted that these were lands that England had conquered from the French as part of Acadia. The Indians replied that it was still Abenaki land and that the French could not pass it on without consulting the Indians. Unimpressed by this, Dudley and his successors treated the Abenaki as British property, which in conjunction with the continued expansion of the British into Maine in the 1720s led to the Dummers War .

Financial problems and end of term

The war worsened currency and financial problems in Massachusetts. Since the 1690s, the provincial government had issued the Massachusetts pound, its own currency, in large quantities, which led to an overall devaluation compared to other currencies based on precious metals. The colonists were split over how to deal with this situation, which remained unsolved into the 1760s. Businesspeople who borrowed money were happy that they could later repay it with devalued currency while lenders called for reforms to stabilize the currency. In 1714, Dudley's opponents proposed that a newly founded Landesbank - secured by the property of its own shareholders - should give 50,000 pounds (around 9,270,000 pounds today) as cash in the market. Dudley, however, convinced the legislature to spend that amount in the form of letters of credit . This later turned out to be the main cause of his political decline.

Research carried out in 1713 showed that the boundary lines between Massachusetts and the Colony of Connecticut had been incorrectly drawn in the 17th century, which is why areas were now part of Massachusetts that had actually been assigned to Connecticut. Dudley negotiated with Connecticut's governor Gurdon Saltonstall that Massachusetts could keep these areas, but Connecticut compensated with other lands of the same size. The " equivalent lands " designated properties covered more than 100,000 acres (404.7 km² ) and were located on both sides of the Connecticut River in what is now northern Massachusetts, southern Vermont and southwestern New Hampshire . In April 1716, these lots were auctioned and Connecticut used the proceeds to establish Yale College .

Six months after Queen Anne's death in 1714, the royal orders for Dudley and his deputy, William Tailer, ran out. The board of governors, dominated by its opponents, took this opportunity and took control on February 14, 1715. In doing so, he relied on the provincial charter, which provided for such a procedure in the event that neither the governor nor his deputy were present. Just six weeks later, the colonial government received a message from England, according to which Dudley's mandate had been confirmed at least temporarily by George I , so that he was reinstated as governor on March 21 of the same year.

However, his political opponents - especially those who had advocated the cash issue - were very active in London and were able to convince the king to appoint Elizeus Burges as the new governor. His appointment was announced on November 9, 1715 in Boston and ended Dudley's assignment. Since Burges was not yet present in the colony, Lieutenant Governor Tailer became the leader of the colony, whose mandate had been renewed. Burges was bribed by Jonathan Belcher and Jeremiah Dummer , brother of Dudley's son-in-law, William Dummer , to reject his appointment as governor without leaving England. Thereupon Samuel Shute was put in charge of the government, who agreed not to set up a Landesbank. Upon his arrival in October 1716, he took office as the new governor and took William Dummer as his lieutenant governor.

Dudley retired to his family home in Roxbury. He advised Governor Shute unofficially and performed some public and private functions. He died on April 2, 1720 and was buried next to his father on the Eliot Burying Ground in Roxbury in a sumptuous ceremony appropriate to his position .

Family and inheritance

In 1668 Dudley married Rebecca Tyng, who outlived him by two years. Together they had twelve children, ten of whom reached adulthood. His son Paul (1675–1751) was a Massachusetts Attorney General and Chief Justice of the Province. The town of Dudley was named after his sons Paul and William, who were the first two residents there.

Dudley owned many lands in Massachusetts at the end of his life, particularly Roxbury and what is now Worcester County . Some of these he had bought the Nipmuck together with William Stoughton , and some he had received in recognition of his proposal to settle French Huguenots , who eventually became part of Oxford . Dudley used his position - especially as President of the Dominion and as governor of the province - regularly to get the rights to land in which he was interested in court cleared for purchase. His friends, relatives and business partners also benefited from this opportunity.

Historian John Palfrey wrote of Dudley that he combined "high intellectual traits with a grouchy soul" and made political connections early in his career to further his own advancement. He capitalized on his family's connections with the Puritan elite in Massachusetts to get contacts to England, but betrayed them as soon as it served his pursuit of further power. Thomas Hutchinson , who later became governor himself, wrote of Dudley: "He had as many good virtues as could coexist with his great thirst for recognition and power." His biographer Everett Kimball characterized him as someone who "apart from his whims had a great deal of tact and charm, which - when all else did not work - enabled him now and then to turn an enemy into a friend."

literature

- Barnes, Viola Florence: The Dominion of New England. A Study in British Colonial Policy (= American Classics ). F. Ungar Pub. Co., New York 1960, OCLC 395292 .

- Colonial Society of Massachusetts (Ed.): Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts . tape 17 . Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Boston 1915, OCLC 559705025 , p. 65 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed January 20, 2015]).

- Crockett, Walter: Fort Dummer and the First Settlements in Vermont . In: Society of Colonial Wars in Vermont (ed.): Year Book of the Society of Colonial Wars in Vermont . Society of Colonial Wars in Vermont, Burlington, VT 1912, OCLC 669377218 , p. 25 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed January 20, 2015]).

- Cutts, John; Winthrop, Robert C .: Letters of John, Lord Cutts to Colonel Joseph Dudley . then Lieutenant-Governor of the Isle of Wight, afterwards Governor of Massachusetts, 1693-1700. John Wilson and Son, University Press, Cambridge, MA 1886, OCLC 769155613 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed January 20, 2015]).

- Drake, Francis Samuel: The town of Roxbury its memorable persons and places, its history and antiquities, with numerous illustrations of its old landmarks and noted personages . Roxbury 1878, OCLC 728958669 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed January 20, 2015]).

- Drake, Samuel Adams: The border wars of New England . commonly called King William's and Queen Anne's wars. C. Scribner's Sons, New York 1910, OCLC 54980935 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed January 20, 2015]).

- Hall, Michael Garibaldi: Edward Randolph and the American Colonies, 1676-1703 . University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC 1960, OCLC 423939 .

- David Hayton, Eveline Cruickshanks, Stuart Handley: The House of Commons, 1690-1715 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge / New York 2002, ISBN 0-521-77221-4 .

- Kimball, Everett: The public life of Joseph Dudley . a study of the colonial policy of the Stuarts in New England, 1660-1715 (= Harvard historical studies . Volume 15 ). Longmans, Green and Co., New York, et al. 1911, OCLC 687882 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed January 20, 2015]).

- Lounsberry, Alice: Sir William Phips, treasure fisherman and governor of the Massachusetts bay colony . C. Scribner's Sons, New York 1941, OCLC 3040370 .

- Martin, John Frederick: Profits in the wilderness . entrepreneurship and the founding of New England towns in the seventeenth century. Ed .: Institute of Early American History and Culture. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill 1991, ISBN 0-8078-2001-6 .

- Massachusetts Historical Society (Ed.): Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society . tape 12 . Massachusetts Historical Society, ISSN 0076-4981 , OCLC 568039830 , p. 412 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed January 20, 2015]).

- McCormick, Charles H .: Leisler's rebellion . Garland Pub., New York 1981, ISBN 0-8240-6190-X .

- Jacob Bailey Moore: Lives of the Governors of New Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay . from the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth in 1620, to the union of the two colonies in 1692. CD Strong, Boston 1851, OCLC 11362972 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed January 20, 2015]).

- Kenneth Morrison: The Embattled Northeast . the elusive ideal of alliance in Abenaki-Euramerican relations. University of California Press, Berkeley 1984, ISBN 0-520-05126-2 .

- John Palfrey: History of New England (= Making of modern law ). Little, Brown, Boston 1858, OCLC 60721741 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed January 20, 2015]).

- George A. Rawlyk: Nova Scotia's Massachusetts a study of Massachusetts-Nova Scotia relations 1630 to 1784 . McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal 1973, ISBN 0-7735-8404-8 .

- Stanley Simpson Swartley: The life and poetry of John Cutts . Press of Deputy Bros. Co., Philadelphia 1917, OCLC 562191837 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed January 20, 2015] plus Diss. University of Pennsylvania, 1917).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c cf. Moore, p. 390.

- ↑ cf. Moore, pp. 294-296.

- ↑ a b cf. Moore, p. 391.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 3.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, pp. 6-10.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, pp. 3-5.

- ^ Roberts, Oliver Ayer: History of the Military Company of the Massachusetts . now called the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts, 1637-1888 (= Library of American civilization 22663-65 . Volume 1 ). A. Mudge, Boston 1895, OCLC 12257590 , p. 245 .

- ↑ cf. Hall, p. 77.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 14.

- ↑ cf. Hall, p. 78.

- ↑ cf. Hall, pp. 79-80.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 17.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 18.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ cf. Hall, p. 85.

- ↑ cf. Hall, p. 83.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, pp. 30-35.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, pp. 35, 47.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, pp. 47-48.

- ↑ cf. Hall, pp. 93-96.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, pp. 50, 54.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, p. 51.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 26.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, p. 55.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, p. 56.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 31.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, p. 58.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, p. 59.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, p. 61.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, pp. 62-63.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, p. 68.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, pp. 33, 36.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 36.

- ↑ cf. Barnes, p. 64.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 41.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 44.

- ↑ a b cf. Kimball, p. 45.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, pp. 48-51.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 52.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, pp. 53-55.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 56.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 58.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 59.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 60.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, pp. 61-63.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, pp. 63-64.

- ↑ cf. McCormick, pp. 357-361.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 64.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 65 f.

- ↑ cf. Hayton et al., Pp. 236-238.

- ↑ cf. Swartley, Cutts, p. Xxxiv.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 66.

- ↑ a b c cf. Kimball, p. 67.

- ↑ cf. Lounsberry, p. 303.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 68.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 69.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 71.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 74.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 75.

- ↑ cf. Moore, p. 399.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 80.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 96.

- ↑ cf. Moore, p. 397.

- ↑ cf. Drake (1878), p. 249.

- ↑ cf. Moore, p. 397 f.

- ↑ cf. Moore, p. 399 f.

- ↑ cf. Moore, p. 398.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, pp. 109-112.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 114 f.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 112.

- ↑ cf. Rawlyk, p. 100.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 183.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 124 f.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 126 f.

- ↑ cf. Drake (1910), p. 270 ff.

- ↑ cf. Drake (1910), p. 275 ff.

- ↑ cf. Drake (1910), p. 208.

- ↑ cf. Drake (1910), pp. 284-290.

- ↑ cf. Morrison, p. 162 ff.

- ↑ cf. Morrison, p. 164 ff.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 161.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 164 f.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 168.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 171 f.

- ↑ a b c cf. Kimball, p. 174.

- ↑ cf. Crockett, p. 24.

- ^ Colonial Society of Massachusetts. Pp. 17: 56-60.

- ^ Colonial Society of Massachusetts. P. 17:92.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 199.

- ^ Colonial Society of Massachusetts. P. 17:65.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 199 f.

- ↑ cf. Moore, p. 401.

- ↑ cf. Moore, p. 402.

- ↑ cf. Massachusetts Historical Society, pp. 12: 412.

- ↑ cf. Martin, pp. 88-97.

- ↑ cf. Palfrey, p. 343.

- ↑ cf. Palfrey, p. 344.

- ↑ cf. Kimball, p. 179.

Web links

- Literature by and about Joseph Dudley in the WorldCat bibliographic database

- Official biography ( memento of October 30, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

| predecessor | Government functions | successor |

|---|---|---|

|

Simon Bradstreet as Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony |

President of the Council of New England May 25, 1686 - December 20, 1686 |

Edmund Andros as Governor of the Dominion of New England |

| Massachusetts Governor's Council | Province of Massachusetts Bay Governor June 11, 1702 - February 4, 1715 |

Massachusetts Governor's Council |

| Massachusetts Governor's Council | Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay March 21, 1715 - November 9, 1715 |

William Tailer |

| Samuel Allen | Province of New Hampshire Governor April 1, 1702 - October 7, 1716 |

Samuel Shute |

| James Worlsey |

Member of the British Parliament 1701–1702 |

John Leigh |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dudley, Joseph |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Massachusetts Colonial Governor |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 23, 1647 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Roxbury , Massachusetts Bay Colony |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 2, 1720 |

| Place of death | Roxbury, Province of Massachusetts Bay |