La rondine

| Work data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | The swallow |

| Original title: | La rondine |

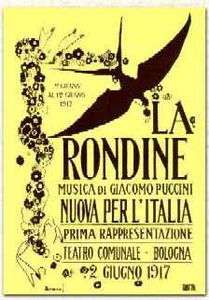

Poster (1917) |

|

| Original language: | Italian |

| Music: | Giacomo Puccini |

| Libretto : | Giuseppe Adami |

| Literary source: | The swallow by Alfred Maria Willner and Heinz Reichert |

| Premiere: | March 27, 1917 |

| Place of premiere: | Monte Carlo Opera |

| Playing time: | about 100 minutes |

| Place and time of the action: | Paris and Riviera, Second Empire |

| people | |

|

|

La rondine (Eng .: The Swallow ) is an opera (original name: "commedia lirica") in three acts by Giacomo Puccini . Originally a commissioned opera for the Carltheater in Vienna , it was premiered on March 27, 1917 in the Monte Carlo Opera House because of the First World War . The libretto is by Giuseppe Adami based on the German model Die Schwalbe by Alfred Maria Willner and Heinz Reichert .

action

first act

Magda's Salon in Paris

The poet Prunier discusses romantic love with his girlfriend Magda and other women in the house of the banker Rambaldo. The ladies mock the poet. Only Magda takes his side. Prunier says that Doretta, the heroine of his latest poem, has been gripped by the virus of romantic love. At the insistence of the ladies, the poet allows himself to be carried away to present his poem. But at the climax of the story, he breaks off and explains that he has not yet come up with a good ending. Magda then sits down at the piano and recites her romantic ending. Everyone is excited. The friends, however, mock Magda for her romantic idealism. Then Rambaldo pushes himself into the conversation and demonstratively gives Magda an expensive pearl necklace. Magda is embarrassed but insists on her belief in true love. Magda's maid enters the room and reports a young man to Rambaldo who wishes to speak to him. With Magda's consent, Rambaldo lets the visitor enter.

Bianca, Yvette and Suzy, Magda's friends, praise Rambaldo's generosity. Magda, however, disagrees. For them, wealth is not everything. She tells how she found true love with a young man in the Bullier ballroom in her youth, but then got cold feet. The friends, disappointed with the outcome of the story, mockingly suggest a new subject for a poem to the poet. The conversation turns to fortune-telling. Prunier wants to read Magda out of her hand and predict the future for her. You retreat to a quiet, secluded corner. Prunier's predictions are ambiguous. Magda could find a good life like a swallow in the sun. However, it would be tragic.

Meanwhile Ruggero has entered. He hands Rambaldo a letter from his father, who is an old friend of Rambaldo's. Ruggero, who is in Paris for the first time, raves about his first impressions: "Parigi è la città dei desideri ..." The guests begin to discuss where newcomers should spend their first night in Paris. It is said that “the first night in Paris is a magical experience”. A few proposals are put down on paper and an agreement is reached on the Bullier nightclub. Lisette shows Ruggero the way.

The guests say goodbye and Magda is left alone. She tells her servant Lisette that she will be staying at home tonight, but that Lisette can enjoy her evening off. When Lisette leaves, Magda thinks about Prunier's prophecy. She roams the room and finds the list of nightspot suggestions. Magda reads this through, calls out loudly "Bullier" and disappears.

Lisette enters the parlor. When she sees that there is no one left, she lets Prunier enter, with whom she has secretly arranged to meet. Both assure themselves of their love and leave after Prunier equips Lisette with a new hat and a new coat, secretly borrowed from Magda. Shortly afterwards, Magda appears in the salon disguised as a grisette , looks at herself in the mirror and then leaves the house.

Second act

Bullier Ballroom

Night owls chat in the ballroom of the Bal Bullier nightclub . Ruggero sits lonely and shyly at a table. Then Magda enters and looks around the hall. She is immediately besieged by students who want to invite her to dance. However, Magda turns them off. She says she has a date with someone. She looks around the hall again, as if to appear, and sees Ruggero staring at her. The students see the eye contact between the two of them, thinking Ruggero is their date, and lead Magda to Ruggero's table. When the students have disappeared, Magda apologizes to Ruggero and explains the whole context to him. When she wants to leave again, Ruggero asks her to stay. After a short conversation, he invites her to dance. She accepts the invitation with the words: "Strange adventure, just like back then".

A lively waltz is played in the ballroom. Magda and Ruggero go into the garden. After a lively dance, the other guests follow them.

Lisette and Prunier enter the ballroom and mingle with the dancing crowd. Ruggero brings Magda back to her table in the meantime. She introduces herself to him as Paulette and tells him about a long time ago visit to the Bullier. Ruggero tells her about his serious, bourgeois attitude towards love and says that he doesn't normally go to such bars. Magda is fascinated by this. It seems to her that Ruggero is exactly the romantic she has longed for. They both kiss passionately. Lisette and Prunier, who have meanwhile come back into the hall, recognize Magda. Magda gives both of them a sign that she does not want to be recognized. Lisette approaches them both and wants to greet them, Magda and Ruggero. Prunier also greets Ruggero, then convinces Lisette that the other person is not Magda, but someone they do not know. After introducing each other, Lisette and Prunier sit down at Magda’s table and order champagne to celebrate life and love.

While the lovers fall into each other's arms, the other guests come by and shower the newly in love with flowers. Then they disappear again. Shortly afterwards, Rambaldo enters the ballroom. Immediately he sees Magda and Ruggero. When Prunier sees Rambaldo, he tries to save the situation. He sends Ruggero and Lisette into the garden. He tells both to take care of the other. Then he approaches Rambaldo, who sends him away. Rambaldo approaches Magda and snubs her. Magda then explains that everything is over between them. Rambaldo disappears and Magda is left alone.

It is now morning. Ruggero steps into the ballroom again and approaches Magda. She describes her fear for her future to him. Ruggero takes her in his arms, they leave the bar together.

Third act

A villa on the Riviera

Despite their poverty, Magda and Ruggero ensure their mutual love. Ruggero confesses to his beloved that he wrote to his father. On the one hand, he asked for financial support and, on the other hand, for his consent to the wedding with Magda. Then Ruggero starts raving about her future. He tinkered an idyllic family picture with a house, garden and a child. When he goes into the house, Magda struggles with her conscience. She wonders if she should tell Ruggero the truth about her past as Rambaldo's mistress. She retreats into the house full of doubt.

Lisette and Prunier enter the villa. Lisette's career as a singer came to an abrupt end after the first appearance. Now she tries to hide somewhere where none of the theatergoers can find and humiliate her. Magda is informed of the arrival of the Parisian friends by the servant and appears. Prunier tells Magda about Lisette's mishap. Lisette, who would like to have her old job again, is hired again as a maid by Magda. After the matter of his dearest loved ones has been clarified, Prunier lets Magda know that Rambaldo would be very happy to resume the old relationship with Magda. He does not mention the name Rambaldos. Then Prunier leaves the villa, not without making an appointment with Lisette for the evening. Lisette, on the other hand, puts on her white apron and goes to work.

Shortly afterwards, Ruggero appears at Magda’s house with a letter from his mother in hand. He thinks he knows what is in it and gives it to his beloved, who should read it aloud. She blesses the union, provided that Ruggero is sure that the woman is worthy of him. Magda's remorse is getting too big after all. She tells him the truth about her past. Ruggero, who doesn't want to know anything about it, forgives her everything. Although he begs her bitterly to stay, she leaves him for the sake of his love. "Time will heal the wounds," says Magda. Then sadly, supported by Lisette, she leaves the unhappy, devastated Ruggero.

Work history

"An operetta , that is out of the question for me," said Puccini in response to an offer from Vienna, "an opera - yes: similar to the Rosenkavalier, only more entertaining and more organic." The offer to write an opera for Vienna was made Puccini presented his opera La fanciulla del West during a trip to the Vienna premiere . He was also offered a princely salary of 300,000 crowns, and he was to receive the royalties and rights to his work. Vienna only wanted the rights for the German language version and the rights for some countries.

From two suggestions from Vienna, Puccini decided on The Swallow . The original libretto was written by Alfred Maria Willner, who had already worked on Franz Lehár's works, The Count of Luxembourg and Gypsy Love , and Heinz Reichert, who was later co-responsible for Das Dreimäderlhaus together with Willner . In this work, Willner and Reichert implemented tried and tested clichés that already guaranteed success with Lehár. They also made use of in Alexandre Dumas ' La Dame aux Camelias and in the Johann Strauss -Werk Die Fledermaus .

In September 1914, Puccini began setting La rondine to music in Torre del Lago, his residence near Viareggio. The First World War , which had just begun, caused him problems . Puccini did not know which side to side with, since Italy remained neutral until May 1915. He was prejudiced against France , which had allied itself with England and Russia , because of its rival Jules Massenet . His friend, the conductor Arturo Toscanini, however, resented Puccini's pro-German attitude. When Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary in May 1915, Puccini sided with his fatherland. On the other hand, he worried about the fate of his operas in Germany and his royalties. He had noticed that Ruggero Leoncavallo's works were boycotted in Germany because he was considered an enemy foreigner in Germany. Leoncavallo had publicly the invasion of Germany in Belgium convicted.

Puccini put the composition of the rondine aside and turned to the opera Il tabarro , which had begun in 1913 . However, soon afterwards, Puccini received a message that there was great interest in an Italian version of his rondine . So he decided to continue his work, as he was meanwhile in possession of the complete worldwide rights to the new opera, with the exception of the rights for Germany and Austria. However, the work turned out to be very difficult at times, as he sometimes almost despaired of this complex libretto. Working with Adami was also difficult, as Adami had joined the army and was therefore rarely available to the composer. In the end, however, the composer was quite satisfied with his work.

However, not everyone shared this view. His publisher Tito Ricordi described La rondine as a “bad Lehár” and did not want to publish the work. Puccini sold the score to the publisher Renzo Sonzogno. Puccini wanted the music of La rondine to be understood as a “reaction to the horrific music of the present, to the music of the world war”. When the opera was to be premiered in March 1917, war was raging everywhere. In France, the French and Germans faced each other in trench warfare; in Russia the revolution was underway and the USA was about to enter the war, as Germany had started a submarine operation against allied merchant ships. Puccini's work was not spared by world events. The French were against a world premiere because this opera had been commissioned by the enemy. In Austria there were voices saying that “Vienna had been cheated out of the world premiere of a Puccini opera”.

Despite all the circumstances, the premiere took place on March 27, 1917 in the opera house of the Monte Carlo Casino. The audience was thrilled. In the same year there were also performances in Milan and Bologna as well as in Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro .

Before the end of the war, Puccini made corrections, additions and cuts. The role of Ruggero, which originally only had to sing a few bars in the first act, was expanded to include an aria. She got the song "Morire", which had already been published in a charity album for the benefit of the Red Cross's war victims and dedicated to the Italian queen. Later, instead of the sad song, the cheerful "Parigi è la città dei desideri ..."

In October 1920 the opera was performed for the first time in Vienna at the Volksoper. The German premiere took place in Kiel in 1927 , the role of Magda was sung by Erica Darbow.

Nowadays this work is extremely rarely found on the repertoire of the major opera houses, including a 2015 production by Rolando Villazón at the Deutsche Oper Berlin , which was also shown at the Graz Opera in January and February 2017 .

The premiere of La rondine in Monte Carlo was the last world premiere of one of his operas that Puccini witnessed himself. A trip so shortly after World War II was not possible when his opera Iltrittico was premiered in New York in 1918 , and Turandot was premiered in 1926, a year and a half after his death.

swell

- EMI Records, recording and text book La Rondine by Christoph Schwandt; 1997

Web links

- La rondine : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project

- La rondine. . Digitized in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna Libretto (Italian), Milan 1928

- La rondine (Giacomo Puccini) in the Corago information system of the University of Bologna

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christine Lemke-Matwey: Kitsch and catastrophe . In: Die Zeit , No. 11/2015