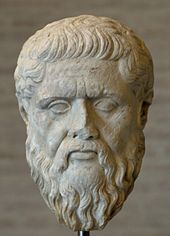

Laches (Plato)

The Laches ( ancient Greek Λάχης Láchēs ) is an early work by the Greek philosopher Plato , written in dialogue form . It belongs to the group of "virtue dialogues", in which virtue and individual virtues are examined. The content is a fictional conversation between Plato's teacher Socrates and the military leader Laches , after whom the dialogue is named, the politician and general Nikias and the distinguished Athenians Lysimachos and Melesias.

Lysimachus and Melesias worry about the upbringing of their sons. They seek advice from Nicias and Laches, from whom they are referred to Socrates. A discussion about pedagogy begins. The starting point is the question of whether it makes sense to train young people in the art of fencing . Everyone agrees that aretḗ (fitness, virtue) is the goal of a good upbringing and that bravery is an essential aspect of fitness. It turns out, however, that it is not easy to determine what constitutes bravery. Several proposed definitions are being examined and found to be inadequate; it is not possible to find a satisfactory definition. The investigation thus initially leads to aporia (perplexity), but the search for knowledge is to be continued on the following day.

In research on the history of philosophy, the main question that is discussed is how the unity of virtues is to be understood in Plato's concept, that is, how the individual virtues relate to one another and to the virtue as a whole.

Place, time and participants

The dialogue takes place in Athens , apparently in a gymnasium . The fighting of the Peloponnesian War forms the current background to the discussions on bravery . The time of the fictional dialogue action is clearly delimited by two datable war events: the battle of Delion in 424 BC mentioned in the conversation . And the death of Laches at the Battle of Mantineia in 418 BC. Within the time frame 424–418 given by this, a further limitation is derived from circumstantial evidence. Dialogue honors Socrates' bravery at the Battle of Delion, but his participation in the more important Battle of Amphipolis in 422 BC. Chr. Remains unmentioned. Perhaps this suggests that the Athenian defeat at Amphipolis is still in the future, but this is only a weak indicator. More conclusive is the conspicuous fact that Lysimachus is not informed about the activities of Socrates. Such ignorance would be after the performance of Aristophanes' comedy The Clouds in 423 BC. BC hardly imaginable, since at the latest from this event Socrates was a well-known figure in the city. It can therefore be assumed that the dialogue acted in the period 424–423 BC. BC falls.

All interlocutors are historical persons. Most of the debate takes place between Socrates, Nicias and Laches; Lysimachos and Melesias, who appear as those seeking advice, do not contribute any ideas of their own. Also present are two boys who only briefly have their say: Aristeides, the son of Lysimachus, and Thucydides, the son of Melesias.

Nicias, the most prominent of those present, was one of the leading Athenian statesmen of his time. As a troop leader, he was known for his cautious, risk-averse demeanor. He was the most notable spokesman for the direction that stood up for an end to the Peloponnesian War and a settlement with the main opponent Sparta . 421 BC He succeeded in the conclusion of the Nicias Peace , named after him , which interrupted the fighting for several years. Laches also strongly advocated the conclusion of peace. He had proven himself in the fighting in southern Italy as a commander of an Athenian armed force and 424 BC. Participated in the Battle of Delion together with Socrates. Lysimachus and Melesias, both of whom were at an advanced age at the time of the dialogue, came from famous families: Lysimachus' father, Aristeides “the righteous”, had earned a brilliant reputation as a statesman during the Persian Wars , and his honesty became legendary . Melesias was one of the sons of the politician Thucydides , who had distinguished himself as the main representative of the aristocratic direction and opponent of Pericles . Unlike their fathers, Lysimachus and Melesias had accomplished nothing significant, as Lysimachus noted with regret. Now they hoped that their sons, to whom they had given the names of their famous grandfathers, would achieve better success and a fame commensurate with their ancestry.

The historical Socrates fought valiantly in the Peloponnesian War, but largely stayed out of the political conflicts in Athens. To what extent the views that Plato attached to his literarily formed dialogue figure correspond to those of the historical Socrates is unclear and very controversial in research.

In the dialogue, Socrates steers the course of the conversation with his questions and suggestions, but appears modest according to his habit and emphasizes the limits of his competence. His intellectual superiority is respected in the group; he is held in high esteem, and the sons of Lysimachus and Melesias also admire him very much.

content

The introductory talk

At the suggestion of Lysimachos and Melesias, Laches and Nikias attended a public, well-attended performance by the well-known fencing master Stesileos. Now Lysimachos tells the reason why the idea arose to attend such an event together. He and his friend Melesias are of the opinion that they have achieved nothing significant in their long life; they compare themselves to their famous fathers, feel ashamed and consider themselves failures. They attribute their inaction and glory to the fact that they were insufficiently equipped for great deeds, because their otherwise employed fathers paid too little attention to their upbringing. They want to avoid this mistake now. They want their teenage sons - each of whom appears to have only one son - to be given the best possible upbringing and training to make them capable men.

Competence or virtue - arete - was a generally accepted ideal in ancient Greek society, the concrete content of which, however, was not clearly defined. The term arete had different connotations in different milieus and epochs . A philosopher like Socrates thought of values such as self-control and justice , he associated different ideas with arete than, for example, an ambitious Athenian from a noble family who orientated himself without reflection on conventional norms and wanted to achieve fame and power by all means. In any case, a traditionally particularly important aspect of arete , which Socrates also recognized, was military combat effectiveness and thus bravery.

In Plato's dialogue, the problem with the two fathers is that they feel very insecure about the implementation of their plan. They do not know what knowledge and skills must be imparted to the young people so that the youngsters can follow the path to success and honor their families in the future. Someone recommended the art of fencing to them, so they came with the boys to the event of the stesileo. Both fathers believe that proper upbringing can prepare a son for a glamorous political and military role as planned. But they don't trust themselves to have the necessary skills. Therefore they seek advice from Nikias and Laches.

Nicias and Laches agree with Lysimachus' considerations. Laches remarks that it is a widespread evil among the Athenian ruling class, that caring for adolescents is generally neglected. A good advisor is Socrates, who has dealt intensively with educational issues. Socrates was not only competent as a theoretician, but had also shown his own prowess through his brave efforts in the Battle of Delion. As it now turns out, the two boys already know Socrates and appreciate him very much. He as an expert is now asked whether it makes sense to give boys fencing lessons. Socrates wants to do his best, but as the youngest in the group does not want to speak first, but asks the others to express their opinions.

The goal of pedagogy

Nikias speaks out in favor of the art of fencing, which, together with riding, is particularly important for young people. It promotes bravery and shows its value especially in individual combat. With this assertion, Nicias professes the view that a technical skill can have an impact on virtue. Laches contradicts, he disagrees completely. In his experience, fencing masters are by no means excellent fighters. None of them has so far distinguished themselves in battle, and Stesileos, who has just performed in front of the crowd, has even made a fool of himself in real combat. The Spartans, famous for their fighting ability, can do without any fencing masters. Laches therefore considers fencing lessons to be militarily insignificant. He thinks it is not a matter of valuable art or technology, but rather a hoax. This does not make a coward brave, but only brazen.

Socrates then explains his fundamental considerations in detail. In his view, it is not just a matter of finding a proven expert and following his professional advice. Rather, one must first clarify what the intended goal actually consists of. The goal must be known before one can reasonably think about the means required. So one has to know what constitutes the skill that is to be taught to young people. First of all, it is important to understand that the question of the art of fencing is not just about training the body, but about acquiring a mental quality. All education aims at the soul . Anyone who wants to lead the soul of a young person to efficiency or virtue must know what is good for it and what is harmful to it. Since Nikias and Laches assume the goal is known and confidently proclaim their opinions about the right course of action, they should know their way around. Strangely enough, however, they have completely opposing views. By pointing out this contradiction, Socrates indicates that there is a fundamental need for clarification. By stating that education aims to make the soul fit for purpose, he distances himself from the common notion that fame is the highest value and that arete is only a means to an end to become famous.

Socrates admits that he himself did not have a knowledgeable teacher. Nobody explained to him how to teach virtue and he does not claim to be able to teach it to anyone, although he has dealt with it since his youth. As a virtuoso teacher, one should know what virtue actually is, but this extensive subject seems too difficult for Socrates for the current debate. He therefore proposes to first examine a sub-question: The aim is to find out what is meant by the term bravery.

The idea of bravery in the pool

For laughs, it is clear what bravery is. He understands it to be the steadfastness with which a fighter endures in the battle order . You are brave if you don't flee, but persevere and repel the onslaught of the enemy. Socrates finds this concept too rigid. He points out that agility can be beneficial; there are situations when it makes sense to retreat or fake escape, and that does not mean a lack of bravery. In addition, the steadfastness in the battle line is only relevant for the heavily armed hoplites , not for the cavalry troops, who practice a more flexible fighting style. In addition, the proposed definition is too narrow, because those who endure illness, material hardship, pain and fear or who resist lust are brave. Even as a politician or a seafarer, one behaves brave or cowardly. The definition must cover all forms of bravery, not just military ones.

Laches then suggests defining bravery as “a kind of perseverance of the soul”. So behavior is no longer the criterion, but inner attitude. But Socrates is not satisfied with this solution either. He draws attention to the fact that then foolish stubbornness should also be regarded as bravery. But if bravery includes the unreasonable, it cannot be considered an excellent quality. In order to avoid this erroneous conclusion, the definition must be made more precise: only persistence connected with reason should be meant. Laches sees that.

But the corrected definition also proves to be inadequate, because reasonable perseverance also occurs in situations that are harmless or only associated with relatively low risks and therefore require little or no courage. To speak of bravery in such cases would be inappropriate or only partially correct. A dilemma emerges here: If you persist in your attitude when you have the situation well under control, you may be acting sensibly, but not bravely, because you risk little or nothing. On the other hand, those who endure under very disadvantageous circumstances, even though they are clearly overwhelmed, act persistently, but not sensibly. Thus, his behavior cannot be described as brave in the sense of the proposed definition. The more competent someone is, the better he is in control of the situation and the less he can be called brave; the more ignorant someone is, the more he dares, but then the more he lacks the common sense of bravery. Laches tries to evade this dilemma pointed out by Socrates by returning to his original conception. Although he has already admitted the need for sensible consideration, he is now turning back to his basic concept, according to which bravery means willingness to take risks and its degree is measured according to the magnitude of the danger to life. Accordingly, the daredevil is particularly brave. If, however, reasonable deliberation does not play a role, bravery becomes an end in itself, and the question of its meaning does not arise. Laches has to admit that he's hit a dead end here. Socrates urges him not to give up, but to bravely endure the investigation.

The Nicias definition of bravery

After Laches failed in his efforts, Socrates asks Nikias for a suggestion. Nicias takes a completely different approach. In contrast to Laches, for whom only doing is important, he considers thinking to be the main thing. Nicias already knows the important Socratic principle that not only is all ability based on insight, but that knowledge is virtue. Accordingly, the knower or wise man (sophós) is good because and in so far as he knows about right and wrong actions. Once he has grasped the nature of virtue, he is necessarily virtuous. Whoever really has knowledge of virtue is inevitably putting it into practice; insight inevitably results in the corresponding attitude and action. Badness is to be equated with ignorance; since the evil one lacks insight, he cannot act well. On the basis of this doctrine of virtues, Nicias defines bravery as that form of expertise, wisdom or understanding (sophía) , which enables one to distinguish the dangerous or terrible (deinón) from the harmless in every situation . Those who are able to do so will always deal with dangers appropriately and appropriately, and that is what Nicias understands to be bravery.

Nikias' suggestion provokes Laches to protest violently. It is obvious to Laches that the skill Nicias speaks of is other than bravery. For example, doctors or farmers have the ability to recognize and correctly assess dangers in their areas of competence; because of that, no one will call her brave. The same is true of a fortune teller if he correctly foresees danger. Nicias replies that this is not what he meant by knowledge of the dangerous and the harmless. Expertise only enables us to assess risks with a view to achieving a given goal. An expert knows how to deal with dangers on the way to a certain goal, but he cannot judge whether the goal itself is meaningful and beneficial. Thus, one does not become brave through specialist knowledge, but rather on the basis of a higher-level knowledge that goes beyond mere specialist competence. It is about the goals themselves, which are to be assessed in terms of their possible harmfulness.

However, Laches is not impressed by these explanations. He makes no secret of his opinion that it is a matter of empty chatter, with which Nicias only wanted to hide his embarrassment. It is completely unclear which specific people should be ascribed bravery in the sense of the proposed definition; perhaps only a god is brave in this sense. Laches thinks he has embarrassed himself because his ideas have turned out to be unsuitable, and now accuses Nikias of insisting on an all the more unusable suggestion instead of admitting his failure, which he - Laches - did after all.

Nicias sticks to his view that what matters is the ability to realistically weigh the risks when choosing goals. Those who cannot do that are not brave, but foolish and fearless out of ignorance. Unsuspecting children are careless, animals are bold and many men are daring, but none of them can be said to be brave. Rather, bravery is a rare quality. Laches disagrees completely. Although he has already agreed with Socrates' conclusion that bravery presupposes reason, he now claims that there are brave animals, and invokes common usage for this; there is general consensus to call animals like lions or tigers brave.

The discussion is deadlocked. The common endeavor to gain knowledge has turned into a personal, polemical argument between Nikias and Laches. This prompts Socrates to intervene and give the conversation a new twist. It struck him that equating bravery with prudent weighing of risks was not Nicias' own idea. Rather, Nikias has adopted a thought that goes back to the sophist Prodikos von Keos . Socrates now critically examines this sophistic approach to a problem. His starting point is the consideration that, according to Nikias' understanding, someone is brave if he knows how to deal with impending dangers. Accordingly, it is about a knowledge related exclusively to evils in the future. However, knowledge is only given if its object is grasped in its entirety independently of time, i.e. the insight gained is equally valid for the past, the present and the future. Thus there can be no special competence with regard to future goods or evils; the expertise that Nicias speaks of is good and bad in general. From this it follows that bravery in the sense of Nicias' definition is to be determined as a comprehensive knowledge of the good and the bad, of the beneficial and of the harmful, whereby according to the Socratic understanding such knowledge always results in corresponding action. In such a comprehensive knowledge, however, all virtues are included; whoever owns it is simply wise and virtuous. With this argument, Socrates shows that Nicias' attempt at definition failed because he failed to work out specific characteristics of bravery and to find a definition that differentiates this virtue from the others.

The result

Nicias has to admit his failure. The dialogue has led to an aporia - an apparently hopeless situation. Laches and Nicias continue their quarrel; they accuse each other again of having failed. Despite his failure and the current perplexity, Nicias remains convinced that he is on the right track. Condescendingly, he holds out the prospect of Lache's future teaching, to which the latter answers ironically.

Thus the search for truth ends with a dissonance. Laches, Nicias and Lysimachus agree, however, that they consider Socrates an excellent educator. Nicias and Lysimachus are eager to entrust their children to his leadership, and Laches would also like to have his sons instructed by him, if they were old enough for that. Socrates evades; he emphasizes his willingness to help, but also points out the limits of his competence. He recalls that it has not yet been possible to find out what the bravery that is to be taught to young people actually consists of. Therefore, none of those present are entitled to pretend to be a qualified teacher. Rather, further efforts to gain knowledge are required. Lysimachus sees that. He admits that despite his old age he is just as in need of instruction as the young people, and asks Socrates to visit him at his house the next day; the discussion on the topic is to be continued there. Socrates agrees with this. That he actually took over the upbringing of Lysimachus' son Aristeides in the following years , albeit with little success, emerges from Plato's dialogue with Theaetetus .

Time of origin

It is almost unanimously considered certain in recent research that Plato is actually the author of the Laches . For reasons of content, form and style, it is one of the philosopher's early works. Whether it belongs to the first or to the later within the group of early dialogues is a matter of dispute in scholarship; there are no conclusive evidence.

reception

Ancient and Middle Ages

In the tetralogical order of the works of Plato, which apparently in the 1st century BC Was introduced, the Laches belongs to the fifth tetralogy. The philosophy historian Diogenes Laertios , who wrote in the 3rd century, counted him to the “ Maieutic ” writings and gave “About bravery” as an alternative title. In doing so, he referred to a now-lost script by the Middle Platonist Thrasyllos .

The ancient text tradition consists of some papyrus fragments. The oldest fragments date from the early 3rd century BC. Chr .; they are relevant for textual criticism .

The oldest surviving medieval manuscript was made in the year 895 in the Byzantine Empire . In the West, the Laches was unknown to Latin- speaking scholars in the Middle Ages .

Early modern age

In the age of Renaissance humanism , the Laches was rediscovered in the West. The humanist Marsilio Ficino made the first Latin translation . He published it in Florence in 1484 in the complete edition of his Latin translations of Plato.

The first edition of the Greek text was published by Aldo Manuzio in Venice in September 1513 as part of the first complete edition of Plato's works. The editor was Markos Musuros .

Modern

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Karl Steinhart , Hermann Bonitz and Hans von Arnim took the view that the definitions proposed by Laches and Nikias were not unusable from Plato's point of view, but only incomplete; the full definition of bravery results from their combination. According to this interpretation, the “Bonitz hypothesis”, the dialogue ends only apparently aporetic. The Bonitz hypothesis is still discussed in recent research and assessed differently.

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff said that the purpose of the dialogue was not to convey philosophical insights, because the definition of bravery had not succeeded; rather, Plato was only concerned with showing his audience the exemplary nature of Socrates. The Plato editor Alfred Croiset praised the character drawing and the verve with which the protagonists stand up for their views. William KC Guthrie found the dialogue entertaining and highlighted the portrayal of the rivalry between Laches and Nicias, the literary quality of which was excellent. Olof Gigon saw in Laches a work that was simple in its scenic, but amiable and significant.

The more recent debate in the history of philosophy revolves primarily around the question of how Plato's Socrates judged the relationship between bravery and virtue in general. It is about the controversially discussed problem of the unity of virtues in research - especially in the English-speaking world . In laughter , Nicias' proposal for a definition fails because of the lack of a distinction between bravery and the overarching concept of virtue. However, according to Plato's understanding, who commented on them in several dialogues, the virtues form a unit. This raises the question of the extent to which a distinction between bravery and overall virtue is necessary at all. It is disputed whether the unity of virtues is to be called identity and whether, when one speaks of identity, it is to be understood as a “weak” or a “strong” identity. A “weak” identity is when whoever possesses one of the virtues necessarily possesses them all; a "strong" one, when there is actually only one virtue and the terms prudence , bravery, justice, wisdom and piety refer to various forms of expression of this one virtue. A strong identity would mean that equating bravery with virtue par excellence, which comes down to Nicias' definition, would not be as wrong as it appears in Laughs . The rejection of this definition in the dialogue would then only be a provisional result in need of revision and ultimately Nikias would be right. As early as the 19th century, the research opinion, which was competing with the Bonitz hypothesis, was put forward that the dialogue figure Socrates and thus also Plato only rejected the brave idea of laughing that was widespread at the time and represented a concept itself that was based on the approach of Nikias, which interpreted the virtues as knowledge and postulate their identity.

Editions and translations

Editions (partly with translation)

- Gunther Eigler (Ed.): Plato: Works in Eight Volumes , Volume 1, 4th Edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-19095-5 , pp. 219–285 (reprint of the critical edition by Maurice Croiset, 4th edition, Paris 1956, with the German translation by Friedrich Schleiermacher , 2nd, improved edition, Berlin 1817).

- Jula Kerschensteiner (Ed.): Plato: Laches . 2nd, revised and improved edition, Reclam, Stuttgart 1982, ISBN 3-15-001785-8 (Greek text without critical apparatus, next to it a German translation).

- Rudolf Schrastetter (Ed.): Plato: Laches . Meiner, Hamburg 1970 (Greek text from the edition by John Burnet , 1903, with critical apparatus and German translation).

- Paul Vicaire (ed.): Plato: Lachès et Lysis . Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1963, pp. 1–61 (critical edition with commentary, without translation).

Translations

- Ludwig Georgii : Laughs . In: Erich Loewenthal (Ed.): Platon: Complete Works in Three Volumes , Vol. 1, unchanged reprint of the 8th, revised edition, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2004, ISBN 3-534-17918-8 , pp. 171-204 .

- Jörg Hardy: Plato: Laches (= Plato: Works. Translation and commentary , edited by Ernst Heitsch et al., Volume V 3). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-525-30418-1

- Rudolf Rufener: Plato: early dialogues (= anniversary edition of all works , vol. 1). Artemis, Zurich / Munich 1974, ISBN 3-7608-3640-2 , pp. 3–39 (with an introduction by Olof Gigon ).

- Gustav Schneider (translator), Benno von Hagen (ed.): Plato's dialogues Laches and Euthyphron . In: Otto Apelt (Ed.): Platon: Complete Dialogues , Vol. 1, Meiner, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-7873-1156-4 (translation with explanations; for Laches : reprint of the 2nd, revised edition, Leipzig 1922) .

literature

Overview representations

- Louis-André Dorion: Lachès . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 5, Part 1, CNRS Éditions, Paris 2012, ISBN 978-2-271-07335-8 , pp. 732-741.

- Michael Erler : Platon ( Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity , edited by Hellmut Flashar , volume 2/2). Schwabe, Basel 2007, ISBN 978-3-7965-2237-6 , pp. 151–156, 600–602.

- Paul Friedländer : Plato . Volume 2, 3rd, improved edition, de Gruyter, Berlin 1964, pp. 33-44.

- Peter Gardeya: Plato's laughter . Interpretation and bibliography . 3rd, extended edition, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2002, ISBN 3-8260-2339-0 .

- Ernst Heitsch : Plato and the beginnings of his dialectical philosophizing . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-525-30145-6 , pp. 35-47.

Comments

- Chris Emlyn-Jones (Ed.): Plato: Laches. Text, with Introduction, Commentary and Vocabulary . Bristol Classical Press, London 1996, ISBN 1-85399-411-1 (the Greek text is a reprint of the edition by John Burnet [1903] without a critical apparatus).

- Jörg Hardy: Plato: Laughs. Translation and commentary (= Plato: Works , edited by Ernst Heitsch et al., Volume V 3). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-525-30418-1

Investigations

- Michael Erler: The meaning of the aporias in the dialogues of Plato. Exercise pieces for guidance in philosophical thinking . De Gruyter, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-11-010704-X , pp. 99-120.

- Bettina Fröhlich: The Socratic question. Plato's laughter. Lit Verlag, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-8258-0185-4 (contains a detailed discussion of earlier research opinions)

- Walter T. Schmid: On Manly Courage: A Study of Plato's Laches . Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale 1992, ISBN 0-8093-1745-1 .

Web links

- Laches , Greek text from the edition by John Burnet, 1903

- Laches , German translation after Ludwig von Georgii

- Laches , German translation after Friedrich Schleiermacher, edited

Remarks

- ↑ Louis-André Dorion: Plato: Lachès, Euthyphron. Traduction inédite, introduction et notes , Paris 1997, pp. 20f.

- ^ Walter T. Schmid: On Manly Courage , Carbondale 1992, pp. 1, 183; Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 151; Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, p. 312.

- ↑ See on Nikias Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, pp. 212–215; Walter T. Schmid: On Manly Courage , Carbondale 1992, pp. 6-11.

- ↑ See on Laches Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, pp. 180f .; Walter T. Schmid: On Manly Courage , Carbondale 1992, pp. 11-15.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 179c – d.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 179d – e. See on Lysimachos and Melesias Debra Nails: The People of Plato , Indianapolis 2002, pp. 194, 198f .; Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 152; Chris Emlyn-Jones: Dramatic structure and cultural context in Plato's Laches . In: The Classical Quarterly New Series 49, 1999, pp. 123-138, here: 124-126, 136f.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 178a – 179e.

- ^ See on the term arete in Plato Dirk Cürsgen: Virtue / Bestform / Excellence (aretê) . In: Christian Schäfer (Ed.): Platon-Lexikon , Darmstadt 2007, pp. 285–290 and the detailed description by Hans Joachim Krämer : Arete bei Platon and Aristoteles , Heidelberg 1959.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 179e – 180a.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 180a – 181d.

- ↑ On the problem of this assumption, see Angela Hobbs: Plato and the Hero , Cambridge 2000, pp. 80f., 86.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 181d – 184c.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 184d – 190c.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 186c, 190b – e.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 190e – 192b.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 192b – d.

- ↑ See on the dilemma Bettina Fröhlich: The Socratic Question , Berlin 2007, p. 67f.

- ↑ Bettina Fröhlich: The Socratic Question , Berlin 2007, pp. 64–67, 91.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 192e – 194b.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 194b – 195a. Cf. Bettina Fröhlich: The Socratic Question , Berlin 2007, pp. 74–79.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 195a – 196a. See Angela Hobbs: Plato and the Hero , Cambridge 2000, p. 100f.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 196a – b.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 196c – 197c. See Bettina Fröhlich: The Socratic Question , Berlin 2007, pp. 70–73, 91–94.

- ↑ See Bettina Fröhlich: The Socratic Question , Berlin 2007, pp. 79–81, 94.

- ↑ On Prodikos in Laches see Walter T. Schmid: On Manly Courage , Carbondale 1992, pp. 24–26.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 197d – 199e. See Bettina Fröhlich: The Socratic Question , Berlin 2007, pp. 95-107.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 199e – 200c.

- ↑ Plato, Laches 200c – 201c.

- ↑ Plato, Theaetetus 150e-151a.

- ↑ An exception is Holger Thesleff , who expresses doubts about the authenticity; see Holger Thesleff: Platonic Patterns , Las Vegas 2009, pp. 358f.

- ↑ Michael Erler: Platon , Basel 2007, p. 152 (research overview); William KC Guthrie: A History of Greek Philosophy , Vol. 4, Cambridge 1975, pp. 124f .; Robert G. Hoerber: Plato's Laches . In: Classical Philology 63, 1968, pp. 95-105, here: 96f.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 3: 57-59.

- ^ Corpus dei Papiri Filosofici Greci e Latini (CPF) , Part 1, Vol. 1 ***, Firenze 1999, pp. 94-118.

- ↑ Oxford, Bodleian Library , Clarke 39 (= “Codex B” of the Plato textual tradition).

- ↑ Hermann Bonitz: For the explanation of Platonic dialogues . In: Hermes 5, 1871, pp. 413-442, here: 435-437; Hermann Bonitz: Platonic Studies , 3rd Edition, Berlin 1886, pp. 216–220. See Bettina Fröhlich: The Socratic Question , Berlin 2007, pp. 120–125.

- ↑ Walter T. Schmid: On Manly Courage , Carbondale 1992, pp. 42-45; Louis-André Dorion: Lachès . In: Richard Goulet (Ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 5, Part 1, Paris 2012, pp. 732–741, here: 739f .; Michael J. O'Brien: The Unity of the Laches . In: John P. Anton, George L. Kustas (eds.): Essays in Ancient Greek Philosophy , Albany 1971, pp. 303–315, here: 308, 312 and note 13; Chris Emlyn-Jones: Dramatic structure and cultural context in Plato's Laches . In: The Classical Quarterly New Series 49, 1999, pp. 123-138, here: 129.

- ^ Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff: Plato. His life and his works , 5th edition, Berlin 1959 (1st edition Berlin 1919), pp. 139–141.

- ^ Alfred Croiset (Ed.): Plato: Œuvres complètes , Vol. 2, 4th edition, Paris 1956, pp. 88f.

- ^ William KC Guthrie: A History of Greek Philosophy , Vol. 4, Cambridge 1975, pp. 130f. and p. 133 note 1.

- ↑ Olof Gigon: Introduction . In: Plato: Frühdialoge (= anniversary edition of all works , vol. 1), Zurich / Munich 1974, pp. V – CV, here: XIX f.

- ↑ See also Louis-André Dorion: Plato: Lachès, Euthyphron. Traduction inédite, introduction et notes , Paris 1997, pp. 171–178; Angela Hobbs: Plato and the Hero , Cambridge 2000, pp. 85f., 108-110; Bettina Fröhlich: The Socratic Question , Berlin 2007, pp. 125–133; Chris Emlyn-Jones (Ed.): Plato: Laches , London 1996, p. 15; Daniel Devereux: The Unity of the Virtues . In: Hugh H. Benson (Ed.): A Companion to Plato , Malden 2006, pp. 325-340; Gerasimos Santas : Socrates at Work on Virtue and Knowledge in Plato's Laches . In: William J. Prior (Ed.): Socrates. Critical Assessments , Vol. 4, London 1996, pp. 23-45, here: 37-42; Paul Woodruff: Socrates on the Parts of Virtue . In: William J. Prior (Ed.): Socrates. Critical Assessments , Vol. 4, London 1996, pp. 110-123. A firm believer in the identity hypothesis is Terry Penner: The Unity of Virtue . In: Gail Fine (Ed.): Plato , Oxford 2000, pp. 560-586. Gregory Vlastos argues against the identity hypothesis ; see his investigations Platonic Studies , 2nd edition, Princeton 1981, pp. 266-269 and Socratic Studies , Cambridge 1994, pp. 117-124.