Munster old town

The old town of Münster , the most important trading and episcopal town in Westphalia since the High Middle Ages , is the historic town center within the promenade ring . It is clearly demarcated by this because the city was strongly fortified for centuries and even developed into a baroque fortress. This green belt was created when the walls and ditches were removed. The area within the promenade ring is to be equated with today's sub-area 1 Münster-Altstadt of the large urban district of Münster-Mitte . This old town area was almost totally destroyed in the Second World War, but was rebuilt in such a way that it has remained an attractive and lively center of the city of Münster and the Münsterland .

Structure of the Old Town sub-area

Old town sub-area

The old town consists of the inner core, the former cathedral immunity , which can still be seen today on the almost circular ring road "Johannisstraße - Rothenburg - Prinzipalmarkt - Roggenmarkt - Bogenstraße - Spiekerhof". The ring is closed by the river Aa . The first episcopal church was built near a ford on the Aa . Around this oldest core, around this clearly delimited so-called Domburg , the medieval township developed, which was then fortified by a wall and later expanded into a fortress town. Today this area defined by the fortress ring - inner ditch, rampart and wall, outer ditch, towers and bastions have largely disappeared - is still clearly recognizable, as it can be walked through a promenade ring and traversed by bicycle.

Within Münster-Altstadt (sub-area 1 of Münster-Mitte), five further city districts can be distinguished, which are defined by the administration as statistical districts with Aegidii (11), Überwasser (12), Dom (13), Buddenturm (14) and Martini ( 15). These quarters of the old town are characterized by their churches and public buildings, the town houses, the arterial roads and the associated former gates.

District of the old town

- Aegidii is the district between Aa and Königsstraße with the parish church of St. Aegidii (Münster) . The main arterial road was Aegidiistraße, which led to the gate of the same name.

- Überwasser is the district west of the Aa around the Überwasserkirche , it extends to the Rosenau, Rosenplatz and Überwasserstraße streets and is the oldest part of the university district. Today it opens to the west to the Schlossplatz with the castle built on the former citadel , which was intended to be the seat of the Westphalian Wilhelms University .

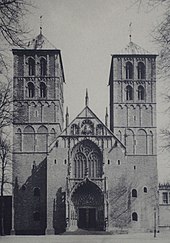

- Dom is the quarter that brings together the former cathedral immunity and the oldest parts of the town. Several churches - St. Paulus Dom , St. Lamberti and St. Servatii - together with the town hall and the town houses on the Prinzipalmarkt are characteristic of this quarter. Today it opens towards the main train station and is of course the main business district within the old town.

- Buddenturm is the quarter in the northwest of the old town with the Buddenturm as a symbol. It is the Kuhviertel to which the densely populated Kreuzviertel adjoins in the north. It extends from the Neutor in the west to the Neubrückentor in the east.

- Martini is the neighborhood to the east around the church of St. Martini . In the middle of the quarter, Hörster Straße leads to the former Hörster Tor, from where Bohlstraße continues east.

History of the old town

As in all cities that have grown historically, the old town of Münster went through an eventful development. Special factors in its development were the contrast between the episcopal city (as Domburg) and the surrounding citizen city in the first few centuries.

The second factor was the late medieval and then the baroque expansion of the city into a fortress and thus the definition of the core city within the fortress belt.

The third factor was the abandonment of the fortress character of the city in the 18th century and the takeover of Münster and the province of Westphalia by the Kingdom of Prussia in 1811. In this epoch, which lasted until the dissolution of Prussia at the end of World War II , the old town was the most serious Changes through.

They were only exceeded by the destruction of the old town during World War II, the changes in the building stock during the reconstruction after 1945 and the structural changes and additions to this day.

Medieval episcopal and Hanseatic city

Foundation of the city

The year 793 is considered the founding year of Münster: On behalf of Charlemagne who founded Friese Liudger on the Horsteberg in the small farming community Mimigernaford or in their immediate environment a monastery ( monasterium ). In 805 a diocese was established in Münster and Liudger was appointed by the Archbishop of Cologne, Hildebold, as the first bishop of Münster. In addition, the settlement was given the status of a civitas ( city ), as a bishop was only allowed to reside in one city, and construction work for the construction of the cathedral began. Around the year 900, a rampart was built around the cathedral, which has grown significantly in the meantime without any actual city rights. Ministerials and craftsmen settled within this Domburg . Because of the sustained economic upswing, market settlements such as the rye market or the old fish market were first established at the gates of the Domburg .

Expansion in the High Middle Ages

Due to the growing community, the Überwasserkirche was founded west of the Domburg in the 11th century and the first church building, the Lambertikirche, east of the spiritual city, was founded as the city's first market church, which was donated by the merchants. In the 12th century, the city burned down completely in the turmoil of the investiture dispute . After the reconstruction and expansion of the previously existing markets, for example through the Prinzipalmarkt , it received town charter around 1170 and in 1173, with Bishop Hermann II von Katzenelnbogen, the first prince-bishop ruler . When the city was completely burned down by another large city fire in 1197, craftsmen and traders were forbidden to resettle within the Domburg. They therefore settled in the markets to the east and thus laid the foundation for Münster's rise to become an important trading center in Westphalia and the creation of the Prinzipalmarkt.

city wall

At the same time as the city was rebuilt, it was decided to build an outer city wall around the market settlements. This city wall was eight to ten meters high, over four kilometers long and provided with a ditch in front. To secure the wall and the ten city gates, six towers were built along them. In the 14th century it was reinforced by an outer wall and a second moat. The course of the city wall is roughly marked by the promenade . With 104 hectares, Münster was the largest city in Westphalia at that time. Later this fortification was reinforced and expanded so that in the 17th / 18th Century could speak of a baroque fortress, especially since the star-shaped citadel of the Prince-Bishop von Galen was in front of it in the west .

End of the baroque fortress city

Contested fortress

During the Seven Years' War , Münster, which Maria Theresa supported, was repeatedly a theater of war. As a result, the city was besieged and conquered several times by the allied warring parties, Electorate Braunschweig-Lüneburg / Kingdom of Great Britain and Prussia, and France, which was allied with the Empress . The city suffered the greatest damage during the siege by the Hanoverians in 1759, when the "Martini Quarter" was completely destroyed by heavy bombardment. When Christian von Zastrow was in command of the citadel, the powder tower exploded inside it.

Elimination of the fortress character

In view of the severe destruction during the war, Franz Freiherr von Fürstenberg , Minister for the Duchy of Münster under Prince-Bishop Maximilian Friedrich von Königsegg-Rothenfels , ordered the demolition of the fortifications after the end of the war in 1764. Münster should be an open city and thus avoid further destruction and devastation. At the request of the Münster population, the prince-bishop approved the construction of a prince-bishop's residential palace at the location of the demolished citadel, i.e. on the western edge of the old town. The construction work dragged on until 1787. It was built - until his death in 1773 - by Johann Conrad Schlaun and then by Wilhelm Ferdinand Lipper . It was also clever who had the former fortifications of the city converted into the Promenade Promenade after their demolition in 1770.

Prussian provincial capital

When Westphalia and with it Münster became Prussian in 1811, only a few Catholic citizens were enthusiastic about the integration into the Protestant kingdom. Münster, which had not grown beyond the fortress ring, became the capital of the province and gradually got the associated institutions and offices. Münster also became a Prussian military base, but this had more of an impact in the outskirts of the growing city in the form of new barracks than in the old town, where old barracks were gradually abandoned.

During the industrial age , Münster's old town went through the same development as many other cities in Germany. However, it was more characterized by its function as a bishopric, government and administrative center than by burdensome industrial settlements. At the end of the empire, members of the clergy , civil servants, the military and the university shaped the city's population, which eventually grew into a large city through incorporation .

As a result, the old town also went through a corresponding change and the larger new buildings and settlements emerged outside the promenade ring. The incorporation of many villages also emphasized the contrast between the expansive city and the densely built-up old town center.

The old town in World War II

The air raids on Münster during the Allied bombing war were devastating for the city. It was exposed to area bombing and suffered well over 100 attacks from the air by the end of the war. The last and at the same time destructive air raid devastated the already badly damaged old town on March 25, 1945: In just under fifteen minutes, between 10:06 a.m. and 10:22 a.m., around 1,800 high-explosive bombs and 150,000 incendiary bombs were dropped from 112 heavy bombers. More than 700 people died in this attack. 32 US aircraft and 22 German aircraft were shot down. A total of 642,000 stick bombs , around 32,000 high- explosive bombs and 8,000 rubber-benzene incendiary bombs are said to have been dropped over the city by the Allied forces during the course of the war . On the evening of Easter Monday, April 2, 1945, Münster was taken without a fight by the 17th US Airborne Division and British armored forces. At that time, only 17 families lived within the promenade ring, i.e. within the old town. So it can be said that the decision of the citizens to preserve the structure of the old town and to rebuild it on the basis of the old property and street boundaries was decisive for the old town and its appearance.

The old town as the core of the big city

During the time that it belonged to Prussia from 1811 to 1946, Münster - and with it the old town as well - went through a tremendous development. A pure residential city and provincial capital became a modern, industrialized city with many new districts and incorporated places. They were the prerequisite for modern development after the Second World War.

The connection to the railway network in Prussia and its further development in the German Empire, the construction of the Dortmund-Ems Canal with the connection canal to the port of Münster, the connection to the road network and later to the motorway network are just a few aspects of the development in the industrial age.

And the old town was necessarily affected in every development phase. It was constantly changing and its functions had to adapt to the requirements of the time. The old town was also drawn into the pull of the city . But when planning the urban development, a different approach was taken to relieve the city center and the old town. University development also had to be taken into account. That is why the Center North relieved the old town, which would otherwise have lost its character too much under the pressure of changes.

To this day, “Part 1 Münster-Altstadt” in the Mitte district has remained the historical heart of the city of Münster and a center of the university city of Münster. At the same time, the center of the Münster diocese was preserved in this old town. For strangers and tourists, this area with its churches, monuments and cultural institutions is the preferred destination when visiting.

European cultural heritage and architectural monuments in the old town

Despite the destruction in the Second World War, the citizens were able to rebuild the old town relatively quickly while preserving the character of the core city in such a way that every visitor gets a vivid impression of its structure and its thousand-year history. The identity of the city of Münster also stands or falls with its old town: the town hall and the Friedenssaal, the Prinzipalmarkt, the cathedral, the Lamberti and Überwasserkirche, St. Agidii and St. Martin are just a few examples of the historical and architectural treasures the old Town.

On April 15, 2015, the European Commission recognized the key role of the Peace of Westphalia for United Europe by awarding the town halls in Münster and Osnabrück with the European Heritage Seal as “sites of the Peace of Westphalia” .

literature

- Bernd Haunfelder , Andreas Lechtape : Münster. City - history - culture. Aschendorff, Münster 2017, ISBN 978-3-402-13211-1 .

- Bernd Haunfelder: Münster. Illustrated city history. Aschendorff, Münster 2016, ISBN 978-3-402-13145-9 .

- Franz-Josef Jakobi (ed.): History of the city of Münster. 3 volumes. 3. Edition. Aschendorff, Münster 1994, ISBN 3-402-05370-5 .

- City Museum Münster, Association Münster-Museum e. V. (Hrsg.): History of the city of Münster. Munster 2006.

Web links

- City history since 793 in the City Museum , accessed on November 29, 2018.

- City history online in the city archive , accessed on November 29, 2018.

Individual evidence

- ↑ http://www.stadt-muenster.de/stadtentwicklung/zahlen-daten-ffekten.html#c36305 The 45 districts of Münster

- ↑ Duds still in the Aatal: Allied bombers targeted the flak position on the outskirts of Mecklenbeck during World War II. In: Westfälische Nachrichten. Münster / surroundings. January 3, 2013.

- ↑ Helmut Müller: five to zero - the occupation of the Münsterland 1945. Münster 1972, p. 115.

- ↑ European cultural heritage seal for Münster's town hall. on: muenster.de

Coordinates: 51 ° 58 ' N , 7 ° 38' E