Margaret Rutherford

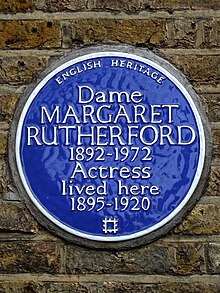

Dame Margaret Rutherford, DBE (born May 11, 1892 in London , † May 22, 1972 in Chalfont St. Peter , Buckinghamshire ) was a British actress .

Margaret Rutherford had her first professional stage appearance at the age of 33, and her breakthrough as a stage actress was beyond the age of 40. Rutherford was best known for her great comedic talent. In addition to her theater work, she appeared in over 50 film and television productions from the 1930s onwards. She gained permanent fame from the early 1960s through the portrayal of the quirky amateur detective Miss Marple in the four British films 4:50 p.m. from Paddington , The Wax Bouquet , Four Women and a Murder and Murderer ahoy! by George Pollock . For her supporting role in the feature film Hotel International (1963) she won an Oscar and a Golden Globe Award .

family

Margaret Rutherford's life was overshadowed by a tragedy nearly ten years before she was born and her mother's suicide . Her parents, William Rutherford Benn and Florence Nicholson, married on December 16, 1882. William Rutherford went through a severe depressive phase during the first few weeks of their marriage and was admitted to the Bethnal House Lunatic Asylum, a mental institution, for the first time in mid-January 1883. In his disease sheet, in addition to depression, excitability and outbursts of anger are recorded. Almost four weeks later, the doctors treating him considered his health to be so improved that he could be discharged. However, his family thought it advisable that he should not return to his wife immediately, but should first relax with his father in Matlock , a then popular hydrotherapy resort on the southeastern edge of the Peak District . Newspaper reports from that time noted that William Rutherford Benn's behavior during the first week of vacation gave no indication that he was suffering from mental disorders. Together with his father, the Reverend Julius Benn, known for his poor relief, he went for long walks and toured the local sights. On the morning of March 4, 1883, however, the guesthouse owner Julius Benn was found dead while his son tried to cut his throat. In the subsequent investigation it was concluded that William Benn had killed his sleeping father with a heavy earthen chamber pot.

During the trial, the mental confusion of William Benn was obvious: his statements before the jury were incoherent, the chairman he addressed as " Pontius Pilate ". On April 6, 1883, he was admitted to Broadmoor Hospital , a carefully secured psychiatric institution that still exists today and which often also accommodates mentally ill offenders. William Benn stayed in this institution until July 26, 1890, when he was released into the care of his wife. Because of their family's fame - William Benn's eldest brother John was now a Member of Parliament and the murder case is still in public memory - the couple changed their family name to Rutherford.

Margaret Rutherford was born in London on May 11, 1892, her birth certificate shows that her father was a merchant in India. Her parents immigrated to India a few months after she was born. According to Tony Benn , a well-known British politician and grandson of William Benn's eldest brother, William Benn worked there as a travel agent and occasional journalist. In late 1894, Margaret's mother Florence, who was pregnant with a second child, committed suicide. In the spring of 1895 William Rutherford returned to Great Britain with his orphaned young daughter and entrusted her upbringing to Bessie Nicholson, Florence's sister. William Rutherford first returned to India, then lived in Paris for some time and was again admitted to Broadmoor Hospital in 1904 after his return to Great Britain. It is no longer clear what led to this second briefing.

childhood

The 44-year-old unmarried Bessie, who spontaneously took in her niece, was living with her brother, his five-year-old daughter and two maids in Wimbledon , a district of London. The Benn family and the Nicholson family agreed that, for their own protection, Rutherford should at least for the time being learn nothing of their parents' fate. Until she was 12 years old, Rutherford believed to be an orphan. She initially received home schooling and attended Wimbledon High School from the age of eight. One of her closest school friends was Clarissa Graves, sister of the later poet and writer Robert Graves . The school annals also record one of Rutherford's first appearances: at the annual school festival, she played a piece by Cornelius Gurlitt on the piano . However, Rutherford traced her desire to become an actress to a private theater performance in which she appeared in a dual role as an evil fairy and prince.

In the spring of 1902, Rutherford was absent from school for a semester. This was repeated a second time in 1904, when she stayed away from school not only for most of the first semester but also the second semester. While there is no explanation for the first, the second, according to Rutherford's biographer Andy Merriman, is related to the discovery of her parents' fate. Rutherford, then twelve, had opened the front door one day and faced a man (resembling a tramp) who brought her greetings from her father. When she told her that her father had died in India, he had told her that he was living very well and was imprisoned in Broadmoor Hospital. Her aunt had no choice but to tell her her family story. Margaret Rutherford reacted to this opening with a depressive phase. According to her close friend Damaris Hayman , Margaret then lived for a long time in fear that her father would escape Broadmoor and do her harm. For the rest of her life she was also concerned that she might prove to be mentally unstable. In 1971 she wrote in her autobiography for the public that her father was a

“A complicated romantic who changed his last name to Rutherford because that was the more attractive last name for a writer. My father tragically died shortly after my mother and so I was an orphan. "

Her aunt finally sent 13-year-old Rutherford to Raven's Croft girls' boarding school in Sussex, where she found the lessons tough but otherwise felt comfortable. At this boarding school she received very extensive piano lessons and there is also very weighty evidence that she received speaking lessons there.

Return to London

In 1911 Rutherford returned to Wimbledon to live again with her aunt, who now lived alone and a little later suffered several strokes, so that she had to rely on Rutherford's help. Rutherford had been obsessed with becoming an actress since she was at school, but initially earned her living as a private piano teacher, for which she had already obtained a corresponding diploma from the Royal Academy of Music in boarding school. Rutherford also obtained a diploma as a speech teacher and eventually gave both piano and speech lessons. Not only aspiring actors were interested in the latter: in Great Britain, correctly articulated English was essential for social advancement, so it was quite common to take speech lessons.

It is unclear to what extent there was contact with her father by letter at this time. In 1909 the British Home Office had rejected an application by the Benn family to release William Rutherford from Broadmoor. The files include a note that his daughter's psychological stability is at risk if she has direct contact with him. The files give an indication that William Rutherford was allowed to write to his daughter - however, the letters were checked by the staff of the institution. William Rutherford kept pushing to see his daughter, but the Benn family intervened in Margaret Rutherford's interests and prevented this. There was no longer any personal encounter between them. The meanwhile physically ill William Rutherford was moved in 1921 from Broadmoor, far from London, to the “City of London Asylum” in Kent because of his ailing physical condition. He suffered two strokes shortly afterwards, contracted pneumonia and died on August 4, 1921 at the age of 66.

In 1923 Bessie Nicholson also died. Rutherford invested her legacy in acting classes. Through a close friend from school, she got in touch with Lilian Baylis , who ran the Old Vic Theater .

Professional career

Theater career

In September 1925 Margaret Rutherford had her first professional stage appearance at the Old Vic Theater . She was 33 years old at the time. In a radio interview on May 31, 1948, announced as It's Never Too Late to Be Happy , Rutherford recalled that moment and linked it to her very first stage appearance in which she played an evil fairy as a child:

“At that time I was almost drunk with happiness - a small flame was lit in me and it stayed burning until I was allowed to step onto the stage of the Old Vic 25 years later. I played the maid at the side of Edith Evans , who gave the portia in the merchant of Venice and I wore a wonderful Venetian dress ... it was happiness beyond imagination for me and it was all the greater because in this long wait the flame was only had glowed, but never completely died. Just a small flame, but for me it is the symbol of happiness. Sometimes it is buried very deep and has to wait a long time before it can light up again. Then we meet the right person, maybe a friend, maybe a husband, or we find the right job ... and then it reignites and we are happy. We may have to go through long periods of darkness and hopelessness for this to happen. But when it happens, it's all the more exhilarating. "

By May 1926, Rutherford appeared in small roles in more than half a dozen productions. However, Baylis informed her in the summer of 1926 that there was no longer any room for her in the ensemble of the Old Vic. During the next two years, Rutherford lived exclusively from piano and speaking lessons, but at the same time did not give up her hope of an acting career. In the fall of 1928 she hired a theater for a second cast, which ultimately only led to a single appearance. It was not until the spring of 1929 that she became a member of the Grand Theater in Fulhalm and appeared in no fewer than 29 different small roles over a period of nine months. The following theater season she hired the Epsom Little Theater and in 1930 she was hired by the Oxford Repertoire Company. In 1931 she played her first major role in this ensemble as Lady Bracknell in Oscar Wilde's play The Importance of Being Earnest . The ensemble also included her later husband Stringer Davis and Joan Hickson , with whom she would be lifelong friends. In 1932 she became a member of the ensemble of the Greater London Players, to which Rex Harrison also belonged, but this engagement also ended at the beginning of 1933. Now 40 years old, she still had great problems making a living as an actress. It was not until 1934, when she played a small tragic role in a play that was staged in London's West End, that theater critics noticed her acting and received positive comments. Tyrone Guthrie , one of the most influential British theater directors, hired her for a role. Again she received positive reviews, but the play was unsuccessful. Rutherford was hired a second time by Guthrie in 1935 for another supporting role in a comedy: Rutherford's portrayal of an elderly villager who purposefully and unscrupulously does everything to make the village festival a success, was once again positively reviewed by theater critics and her fight with Rex Harrison a phone that Rutherford kicked and described as the comedic climax of the play. Despite these successes, Rutherford struggled to find further engagements.

Film career

In 1936, Rutherford played her first film role as a female member of a gang of counterfeiters in the feature film Dusty Ermine . Her final breakthrough came in 1939 with the role of Miss Prism in the Oscar Wilde classic The Importance of Being Earnest , a prime role that she also played in the 1952 film adaptation . Because of her quirky, energetic appearance and her unmistakable appearance, she is often referred to as the "English Adele Sandrock " in German-speaking countries .

To this day, she has a large fan base, especially in Germany, which she owes mainly to the portrayal of Miss Marple in four popular films. Agatha Christie was disappointed with the film adaptations, because Rutherford's boyish-cheeky portrayal was a far cry from the good-natured-minded detective invented by Christie. During the filming, however, both women met personally and became close friends. Christie dedicated the novel Mord im Spiegel to her in 1963 , which was filmed in 1980 with Angela Lansbury in the role of Miss Marple.

Rutherford played in many other films and was mostly set on rather quirky characters. For the portrayal of the bankrupt Duchess of Brighton in the film Hotel International , she won an Oscar and the Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress in 1964 .

Next life

In 1961 she was appointed Officer of the British Empire appointed (OBE) and 1967 for their successful work in the theater of the British Queen Elizabeth II. As a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in the knighthood raised. Shortly before her death, she published her biography entitled Margaret Rutherford. She once described her career in short words:

"My success came late, but - if I may say so - in a sensational way."

In 1945 Rutherford married the English actor Stringer Davis after a relationship of 15 years . Together they played in a number of films, including the four Miss Marple films in which he played the character of the librarian Mr. Jim Stringer (who does not appear in the books and whose role was added at Rutherford's request), as well as that of the porter in Hotel International. In the early 1960s, they took in the writer Gordon Langley Hall, who became a woman in one of the world's first sex reassignment operations in the late 1960s and then wrote numerous books under the name Dawn Langley Simmons (including a biography of Rutherford).

In old age she suffered from Alzheimer's disease . She died in 1972, eleven days after her 80th birthday, of complications resulting from dental surgery. She was buried in the graveyard of St. James Church at Gerrards Cross , Buckinghamshire . Her husband, who was buried next to her, died in August 1973. After the deaths of Margaret Rutherford and her husband, Stringer Davis, their housekeeper forged the will and sold the stolen valuables. Among them was Margaret Rutherford's Oscar, which has not reappeared to this day. The housekeeper was never charged for this.

Filmography (selection)

- 1936: Dusty Ermine

- 1941: Quiet Wedding

- 1945: Ghost Comedy (Blithe Spirit)

- 1947: The Last Duel (Meet Me at Dawn)

- 1948: Miranda

- 1949: Blockade in London (Passport to Pimlico)

- 1950: The Happiest Days of Your Life

- 1951: The Wonderful Flicker Box (The Magic Box)

- 1952: The premiere takes place after all (curtain up)

- 1952: Being Earnest ( The Importance of Being Earnest )

- 1953: Me and the director (Trouble in Store)

- 1954: The inheritance of Aunt Clara (Aunt Clara)

- 1955: An alligator named Daisy (An Alligator Named Daisy)

- 1957: The smallest show on earth (The Smallest Show on Earth)

- 1957: A Sparrow in the Hand (Just My Luck)

- 1959: Young man from a good home (I'm All Right Jack)

- 1961: 4:50 p.m. from Paddington (Murder She Said)

- 1961: General Pfeifendeckel (On the Double)

- 1963: Even the little ones want to go up (The Mouse on the Moon)

- 1963: Hotel International (The VIPs)

- 1963: The Gallop (Murder at the Gallop)

- 1964: Four Women and One Murder (Murder Most Foul)

- 1964: killer ahoy! (Murder Ahoy)

- 1965: The ABC Murders (The Alphabet Murders) - Cameo -Auftritt as Miss Marple

- 1965: Falstaff - Bells at midnight (Chimes at Midnight / Campanadas a medianoche)

- 1967: The Countess of Hong Kong (A Countess from Hong Kong)

Theatrography (selection)

1925–1926 season at the Old Vic Theater, London

- The Merry Wives of Windsor (The Merry Wives of Windsor)

- Julius Caesar

- Much Ado About Nothing (Much Ado About Nothing)

- Romeo and Juliet (Romeo and Juliet)

- The Shoemaker's Holiday

- The Taming of the Shrew (The Taming of the Shrew)

- Measure for Measure (Measure for Measure)

- Antony and Cleopatra (Antony and Cleopatra)

- The Merchant of Venice (The Merchant of Venice)

Prince's Theater in Bristol

- 1935-1936: Short Story

- 1938–1939: Spring Meeting

- 1939-1940: The Importance of Being Earnest

Other stage appearances

- 1936–1937: Farewell Performance at the Lyric Theater, London

- 1937–1938: Spring Meeting at the Ambassadors Theater, London

- 1938–1939: The Importance of Being Earnest at the Globe Theater, London

- 1939–1940: Rebecca at the Queen's Theater, London

- 1941–1942: Blithe Spirit at the Piccadilly Theater, London

Awards

- 1963: National Board of Review Award for Hotel International ( Best Supporting Actress )

- 1964: Golden Globe Award for Hotel International ( Best Supporting Actress )

- 1964: Oscar for Hotel International ( Best Supporting Actress )

- 1964: Laurel Award for Hotel International (Best Supporting Actress)

literature

- Margaret Rutherford: An Autobiography. As told to Gwen Robyns. Reprinted. Allen, London 1972, ISBN 0-491-00379-X .

- Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. Aurum, London 2009, ISBN 978-1-84513-445-7 .

- Klaus F. Rödder: "They have their methods - we have ours, Mr. Stringer". Boesche, Berlin et al. 2009, ISBN 978-3-923809-87-5 .

- Dawn Langley Simmons: Margaret Rutherford. A Blithe Spirit. Sphere, London et al. 1985, ISBN 0-7221-7861-1 .

- Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. the actress behind Miss Marple. Weber, Landshut 2011, ISBN 978-3-9809390-8-9 .

Television documentaries

- The Real Miss Marple - The Margaret Rutherford Case. Director: Rieke Brendel , Andrew Davies , Germany, 2012.

Web links

- Margaret Rutherford in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Margaret Rutherford in the Internet Broadway Database (English)

- German fansite

- Margaret Rutherford in the German synchronous file

Individual evidence

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 7.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 8.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 9.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 9.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 10.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 11.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 12.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 12.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 12.

- ↑ Quoted from Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 15. The original quote is: “ … complicated romantic who changed his name to Rutherford as it was more aesthetic for a writer. My father died in tragic circumstances soon after my mother and so I became an orphan. ”

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 20.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 21.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 23. The note on the file reads: "His daughter's sanity would be endangered if she would be allowed to associate with him."

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 21.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 24.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 25.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. S. 104. The original quote is: “ Suddenly I knew an intoxicating happiness - a little flame lighted up inside of me and kept burning until, twenty-five years later, I walked on stage at the Old Vic, in a lovely Venetian dress as Lady-in-Waiting to Edith Evans, who was playing Portia in The Merchant of Venice - it was happyness beyond all imaginings - the greater because, in that long waiting time, the little flame had burnt very low, but it had never quite gone out. A little flame, I like this as a symbol of happiness. It is in the heart of the black coal, buried deep in the earth for hundreds of years, waiting to be set free. Then suddenly we meet the right person, perhaps a friend, perhaps a husband, or we find the right work. Our imagination is kindled and the spark bursts into life - we are happy. We may have passed through long periods of darkness, of hopelessness, waiting for this to happen, and when it does it is all the more wonderful. ”

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 30.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 32.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 36.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 40.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 44.

- ^ Andy Merriman: Margaret Rutherford. Dreadnought with Good Manners. P. 44.

- ^ Neil Norman: Miss Marple's torment. September 25, 2009, accessed December 2, 2019 .

- ^ Knerger.de: The grave of Margaret Rutherford and Stringer Davis.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Rutherford, Margaret |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Rutherford, Lady Margaret Taylor (full name and title) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British actress |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 11, 1892 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | London , England , United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 22, 1972 |

| Place of death | Chalfont St. Peter , Buckinghamshire , England , United Kingdom |