Munir Bashir

Munir Bashir ( Arabic منير بشير, DMG Munīr Bašīr , Aramaic ܡܘܢܝܪ ܒܫܝܪ) - Other transcriptions are also in use - (* 1930 in Mosul , Iraq ; † September 28, 1997 in Budapest , Hungary ) was an Iraqi musician and in particular a style-setting virtuoso on the oriental short-necked lute , the oud . He was one of the first Arab instrumental musicians to become known in Europe and America. His music is characterized above all by a new style of improvisation , which, in addition to oriental forms, also reflects Baschir's study of European and Indian musical art.

Life

Mosul

Munir Bashir was born in Mosul, northern Iraq. With regard to his date of birth, the information from various sources differ from one another and vary between 1928 and 1930. Bashir comes from an Assyrian (i.e. Christian ) family that has produced influential musicians for generations. For example, his father 'Abd al-Aziz and his brother Jamil Bashir (1921–1977) were known as Munir himself as outstanding oud soloists and singers; an authoritative textbook for the oud comes from Jamil. The family began the musical education of young Munir when he was five years old. He first learned the cello - this European instrument had gradually become a popular bass instrument in Arabic music since the late 19th century . At the same time, his relatives taught him singing and the oud. Instruction in the use of the lute is important because it plays a similar role in Persian-Arabic music as the piano does in European music : it is the instrument that is used to convey the important theoretical music content.

Northern Iraq has a particularly rich musical past because a wide variety of styles and traditions have been mixed here for centuries. In this environment, Munir Baschir also made early acquaintance with classical Turkish , Persian and Kurdish music .

Baghdad

At the age of six the family sent the talented Munir to the Conservatory in Baghdad , which was founded in 1934 by the important Iraqi musicologist Sharif Muhyi 'd-Din Haydar Targan (1892-1967). Already during his studies, but increasingly after his graduation, Bashir devoted his particular attention to the documentation and preservation of the traditional musical styles of his country. Due to the turbulent history of Iraq in the 20th century , among other things, these were in a progressive process of being reshaped by “Western”, i.e. European and American music, especially its more commercial varieties.

In 1951, Bashir took on teaching assignments for oud and Arabic music history at the newly founded Institute of Beaux-Arts in Baghdad, and he also worked as an editor for Iraqi radio.

Beirut

Bashir's relationship to his homeland was always ambivalent: on the one hand, he felt deeply rooted in the rich cultural heritage of Mesopotamia, on the other hand, Iraq experienced practically no phase of internal stability during the musician's lifetime. The 1950s and 60s in particular, i.e. the last years of the Hashimite monarchy and the period of constant military coups that followed the fall of Faisal II in 1958, almost forced Bashir to pursue his musical work abroad.

Since his call to Beirut had already preceded him, the legendary Lebanese singer Fairuz immediately signed him as a companion and “star soloist” when he first traveled to the Lebanese capital in 1953. While he got to know other varieties of US and Latin American popular music through Fairuz, he simultaneously intensified his research on the musical traditions of the Middle East. Due to his profound knowledge of music theory, he was given teaching positions at the music academies in Baghdad and Beirut.

The years 1953 and 1954 also mark the beginning of Bashir's career as an instrumental virtuoso. A first public solo concert took place in Istanbul in 1953 , and in the following year the 23-year-old received a feature on Iraqi television. In 1957 he began touring that took him to most of the European countries; The difficult political situation in his home country and the resulting problematic working conditions for a musician made him leave Iraq permanently in 1960.

Budapest

After another stay in Beirut in the meantime, Bashir settled in Budapest in the early 1960s , where he was to maintain a residence until the end of his life: he married a Hungarian, their son Omar was born in 1970 in the Hungarian capital. This city was not only attractive to the Iraqi as a European music metropolis, but also because it offered him the opportunity to study at the Franz Liszt Conservatory (Liszt Ferenc Zeneakadémia) with Zoltán Kodály , where he received his doctorate in musicology in 1965 . Kodály, in collaboration with Béla Bartók, had made a great contribution to the preservation of traditional Hungarian songs . In terms of objectives and methodology, this corresponded very largely to Baschir's commitment to folk and art music in his homeland.

After Kodály's death in 1967, Bashir stayed in Beirut again for some time. However, the development of Arabic music, which he saw marked by progressive degeneration and commercialization due to the incompetent and uncritical handling of Western influences, repelled him: Since he considered the popular singers of the time to be the main responsible for this trend, he refused henceforth to accept engagements with them.

Ambassador of Iraqi Music

In 1973 the Iraqi Ministry of Information appointed Bashir to its culture committee; the Ba'ath Party regime had not yet firmly established itself at this point and found in it, as a member of the Christian minority, a figure of cultural integration. Because of his international fame, Bashir, who appeared to be rather apolitical, seemed a suitable personality to represent the different ethnic, religious and political groups of his homeland. In 1981, when Saddam Hussein was already in power and de facto power was increasingly being passed to the Sunni population, the regime nevertheless supported the establishment of Bashir's 40-strong Iraqi Traditional Music Group , which was committed to the diversity of Iraqi culture. Bashir was temporarily artistic advisor in the Ministry of Culture, President of the National Music Committee of the Republic of Iraq and Secretary General of the Arab Music Academy.

In 1987 - the First Gulf War was still going on - Bashir succeeded in realizing a long-cherished project with the help of his international reputation: This year the Babylon International Festival for Dance, Music and Theater took place for the first time , and he still has a few more For many years as artistic director.

However, Bashir himself stayed only sporadically in Baghdad and left the country for good after the Second Gulf War in 1991. Guest performances, especially in Europe, offered him a large, open-minded audience and thus an excellent platform for the presentation of his now distinctly independent style of improvisation and composition . Accordingly, the majority of his major recordings also took place in Europe. In the last years of his life, Baschir set himself the goal of "building" his son Omar into his musical heir. A duo recording with Omar from February 1994 is today considered a classic in Baschir's oeuvre because it combines traditional, largely folk-song-like material with highly artistic improvisation techniques in an exemplary manner.

Munir Baschir died of heart failure in Budapest in 1997, shortly before the planned departure for a concert tour to Mexico .

Instrumental style

General characteristics

In the long history of the oud, Munir Bashir is considered one of the most important exponents of this instrument. His style differs significantly from that of other important oudists of the 20th century, such as the urban "showmanship" in the "typical Egyptian" game by Farid al-Atrache or the strongly jazz-oriented music of the Lebanese Rabih Abou-Khalil, who is very popular in Europe .

Especially in the area of solo improvisation (Arabic taqsim ) on the scales commonly used in Arabic music ( maqam , plural maqamat ), many experts and colleagues cite him as an unsurpassed master. It is certainly due in large part to Bashir's pioneering work that oudists can now give solo recitals in concert halls all over the world.

On the other hand, in the course of his musical development, he turned more and more sharply against the clichés that represent an oriental equivalent to the much smiled at western "campfire guitar" , especially when accompanied by vocals for commercial Middle Eastern music on the oud.

Moods

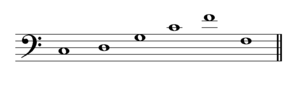

In many musical idioms it is part of the tradition of stringed instruments to work with different tunings of the strings that are adapted to the requirements of a piece . It is therefore not surprising that a musician of the Bashir ranks experimented with a number of moods of the oud. A very common standard tuning of the Arabic oud ("Arabic" here in contrast to the almost identical Turkish instrument, which has a slightly different story) is:

Building on the older traditions of the Iraqi oudist school (for example his older brother), Munir Bashir developed a typical mood that is mostly named after him today:

The doubling of the “actually” highest choir on F is noticeable by another, higher-lying, but one octave lower, F-choir. This trick enables a particularly full sound of the high melody choir and meets Baschir's pronounced interest in melodic design possibilities.

Another mood has already been developed in a similar form by other members of the Bashir family. Here, the player uses an F-bass string choir that is tuned one octave lower than in the example above; Optionally, two F strings can be wound octave apart. With this tuning of the instrument, the bass choirs on the edge of the fingerboard frame the melody choir in the middle, so to speak. An oud tuned according to the described method usually has a very full sound and allows unusual melodies, but such a complicated tuning system places high demands on the musician's fingering and plucking technique.

Plucking technique

Baschir's exploration of foreign musical forms is also evident in his experiments with alternative plucking techniques. Striking the strings with his fingers, as it was cultivated on the guitar - especially in flamenco - he made an essential feature of his mature style. After brief experiments, he refrained from using a plectrum in the form of a thumb ring ( mizrab ), as he had got to know while studying the Indian sitar .

ornamentation

The taqsim improvisation, which Bashir used as the preferred genre, draws its charm from the intelligent, complicated rules-following ornamentation of melodies or familiar melodic fragments. A taqsim thus develops on the basis of significantly different, but by no means less artistic, criteria than the improvisation known from modern jazz within a relatively strict metric , harmonic and formal grid. Another similarity to jazz improvisation is that certain patterns are heard in close connection with their “creator”. In this sense, the listener who is familiar with Arabic music recognizes countless “bashirisms” today, as the jazz fan can unequivocally identify the influence of Louis Armstrong or Charlie Parker in certain melodic turns .

Expansion of the tonal range

As mentioned, the oud belongs to the short-necked lute family: the largest interval that the player can touch between the open string and the end of the fingerboard is no more than a fifth . However, it is possible to play larger intervals on the same string by tapping notes on the top of the body . Even if Munir Baschir did not invent this somewhat unorthodox technique, he integrated it into his style in a particularly exemplary manner.

Likewise, the use of harmonics before Bashir was not part of the traditional canon of playing techniques on the oud, although this method of sound generation is actually characteristic of stringed instruments.

Foreign influences

Bashir's occasional somewhat polemical commitment to the authentic means of expression in Arabic music did not arise from a rigorous internal perspective. He was a comprehensively educated and interested musician, who throughout his life showed a marked openness to non-Arabic styles, paying particular attention to European and North Indian (Hindustan) music.

This profound expertise enabled him not to include foreign influences in his music as mere incoherent quotations, but to incorporate them convincingly into the traditional canon of “his” music.

To make things clearer, Baschir's way of working is shown using a particularly spectacular example. The duo recording with his son Omar features Bashir's own composition Al-Amira al-Andaluciyya (“The Andalusian Princess”) with the opening motif, which is very unusual in the Arabic context,

The C Major - triad arpeggio ( motif a), which opened the piece would be in European music an exceptionally banal phrase - on the oud is a completely unusual musical gesture, as the Arabic music practically straight major triads in this form used. The play around the note C (motif b) then points to the musical connotation actually intended by the composer ( Andalusia , for centuries a province of the caliphate and home of flamenco ). With the help of just two tones (Db and Bb), the major sound "tips" into the Phrygian key that is so typical of flamenco , whereby the tremolo-like decoration of the top note Db intensifies this effect. The line descending to G (motif c) then establishes the key in which the following improvisations will take place - maqam Hijaz Kar Kurd , which (in a simplified form) has this structure:

The asymmetrical structure of this material scale requires different guidance of ascending and descending melody lines and is therefore ideal for flamenco-like improvisations, as this style is characterized by a typical ambivalent, unstable relationship to the major-minor tonality. The latter is naturally completely alien to Arabic music, which knows no harmony .

As the improvisations progress, Baschir draws on another, very virtuoso effect by playing numerous chords . These so-called rasgueados are an indispensable stylistic element of the flamenco guitar. On the oud as a fretless instrument, however, they are extremely difficult to intonate properly .

Influence and reception

Importance for Arabic music

Munir Bashir entered the scene at a time that was anything but favorable for Arabic music. Due to his professional experience and his cosmopolitanism, he was more aware of these difficulties than many of his colleagues, who often tended to withdraw into niches or to come to terms with the circumstances more or less resignedly. Bernard Lewis , the British historian , cites the musician as an example of an Arab who has understood how to counter the influence of Western culture on the basis of equal cooperation. By advocating the traditions of "his" music and dealing with older forms, Baschir sought and found new possibilities for musical expression.

On a more technical level, Bashir placed his improvisations in the context of more obscure maqamat that were never in use outside Iraq or had been forgotten in the course of the 20th century.

criticism

Bashir's inclusion of foreign stylistic elements occasionally met with incomprehension and criticism from traditionalists. As the music journalist Sami Asmar reports, the accusation surfaced that Bashir was in favor of his western audience by preferring to make music in maqamat , which are particularly "simple". The allegation went in detail that Bashir abused the maqamat Rast and Shadd Araban in this way. The mentioned keys look like this (again in a simplified form):

(A longer excerpt from ataqsimrecorded by Bashirin this key can be found under the web links)

Now it is true in the context of Arab culture that maqam Rast is perceived as a very basic key, comparable to the situation of C major in Europe. For the European listener, this sound quality - roughly the Doric key using quarter-tone intervals - is in no way particularly catchy. In Shadd Araban , it is the use of two 1½ tone steps that makes the scale rather abstract and unsangible to the Western ear.

Apart from the less than convincing assumptions on which the criticism mentioned begins, it is also not supported by Munir Bashir's record work. At least in the recordings, a preference for the keys mentioned cannot be made tangible, and there is no evidence that Bashir could have behaved differently during live performances. It would be much easier to show that Bashir prefers those maqamat that allow great melodic freedom and imply a strong tonal ambivalence for the harmonious European ear, as shown above for Hijaz Kar Kurd .

Honors

For his musical work and his commitment to the dialogue of cultures, Bashir was also recognized internationally, especially in his final years. Among other things, he was Vice-President of the UNESCO Music Council, Knight of the French Legion of Honor and General Secretary of the Arab Music Academy in Baghdad.

Selected discography

- Recital - Solo de Luth Oud, Live in Geneva (Club du Disque Arabe AAA003)

- L'Art du 'Ud / The Art of the' Ud (Ocora C580068)

- Flamenco Roots (Byblos BLCD 1002)

- Raga Roots (Byblos BLCD 1021)

- Duo de 'Ud, with Omar Baschir (Auvidis B 6874)

- Munir Bashir & the Iraqi Traditional Music Group ( Le Chant du Monde 274 1321)

- Meditation - improvisation on the 'Ūd (Eterna 835085)

literature

- Sami Asmar: The Musical Legacies Of Sayyid Makkawi, Munir Bashir and Walid Akel. In: Al-Jadid. A Review and Record of Arab culture and arts. Los Angeles born 4.1998, H 23.

- Bernard Lewis: The Arabs . dtv, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-423-30866-4 .

- Christian Poché: Snapshot: Munir Bashir. In: Virginia Danielson, Scott Marius, Dwight Reynolds (Eds.): The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Volume 6. The Middle East. Routledge, New York / London 2002, pp. 593-595.

- Amnon Shiloah: Arabic Music. In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present . Bärenreiter, Kassel 1998, ISBN 3-7618-1100-4 .

- Habib Hassan Touma: The Music of the Arabs . Amadeus Press, Portland (Oregon) 1996, ISBN 0-931340-88-8

(The article uses its own transcriptions and analyzes of Bashir's recordings)

Web links

Music theory, biography

- Website of the oud expert Dr. David Parfitt

- Comprehensive website about the oud

- Excellent, easy to understand introduction to Arabic music theory

- Encyclopedia of the Orient

- Sara music

Audio samples

- Excerpt from the duo improvisation with Omar on the folk song Fog en-Nakhel (MP3 file; 469 kB)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bashir, Munir |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Bashir, Munir; Bachir, Mounir; Bachire, Mounir; Bašīr, Munīr |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Iraqi musician |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1930 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mosul |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 28, 1997 |

| Place of death | Budapest |