Muqali

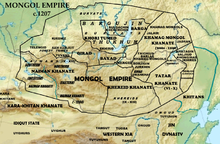

Muqali ( Central Mongolian : ᠮᠣᠬᠣᠯᠢ , Muqali; Mongolian (modern) : Мухулай, Muchulai; Chinese : 木华黎, Mùhuálí; * around 1170 in what is now Mongolia ; † 1223 in China ) was one of the most important commanders of the army of the Mongol Empire under Genghis Khan . Muqali was involved in decisive, victorious battles during the unification of the Mongol tribes and during Genghis Khan's campaign against the Jin Dynasty he won numerous battles and took several cities. He was one of Genghis Khan's closest advisers and confidants and was instrumental in the founding and early expansion of the empire.

In 1217 Genghis Khan gave him the title Gui Ong (roughly: state prince) and made him de facto ruler over the Mongolian territories in northern China and commander in chief of the troops there. He was not only responsible for the administrative management of the occupied territories, he also expanded it until his death in 1223. Only Genghis Khan himself stood above him in the administrative and military hierarchy of the Mongols, and he was the most senior official and officer who did not come from the Genghisid clan.

While Muqali played an important role in the Mongolian tradition of later centuries and is still very popular today, in comparison to other Mongolian generals - such as J Feldebe or Sube'etai - he has remained relatively unknown.

Life

Information about Muqali's life is sparse in the primary sources. Information about his early years and the beginning of his career can only be found in the Secret History of the Mongols and in the Chinese Chronicle Yuan shi (History of the Yuan , approx. 1370). The latter contains a biography of Muqali, but this has not been translated into Western languages. His later military operations are scarce in Chinese sources but relatively well documented. In the secondary literature, information about his person and his work is often sparse and widely scattered. Contiguous representations can only be found in highly condensed, biographical sketches and isolated academic articles or chapters in longer publications.

Origin, early years and family

Neither Muqali's date of birth nor the exact place of his birth are known and there is no information in the sources about his childhood and youth. He came from humble backgrounds. His family belonged to the Mongolian clan of J̌alayir. These lived east of the Onon River , northeast of the settlement area of the Qiyat, Genghis Khan's clan.

Muqali was one of five sons of his father Gü'ün U'a and his mother Köküi. He had a main wife named Buqalun and eight concubines, although their names have not been recorded. With Buqalun he obviously had only one son, Bōl (* 1197). This inherited Muqali's title and position and was also a commander in the Mongolian army, just like his own son Tas later.

Connection to Genghis Khan

For generations, the J̌alayir were in a bondage relationship with the J̌ürkin clan, who, like Genghis Khan's Qiyat, were a subclan of the Borjigin. They traced their ancestry back to Qabul Khan and belonged to the aristocracy of the Mongolian clans and tribes. In the dispute for supremacy on the Mongolian plateau, probably in 1196 or 1197, there was a battle between the warriors of Temüdschins, who later became Genghis Khan, and the J̌ürkin. The latter were defeated, and after his masters were defeated, Gü'ün U'a appeared to Genghis Khan to express his submission. As a token of his sincerity, he gave Genghis Khan his two sons Muqali and Boqa as a bargaining chip. A close personal relationship quickly developed between Temüdschin and Muqali, who as a Nökör (companion) soon belonged to Temüdschin's closest circle.

As a general

Besides Bo'orču, who had already become Temüdschin's first follower in his youth, Muqali became Temüdschin's closest confidante and advisor. In 1206, on the occasion of Temüdschin's enthronement to the Činggis Qan , Muqali was given the highest honor. Temüdschin proclaimed that Muqali and Bo'orču were his most loyal and cherished nökör and that he owed his rise to power to them. He assigned each of the two a personal tower (tens of thousands of the Mongolian army) and gave Bo'orču the command of the right (western) army wing, Muqali that of the left (eastern), while the Khan himself commanded the troops in the center. In addition, Genghis Khan made Muqali one of his Dörben Kulu'ud (four horses). The Dörben Kulu'ud , Muqali, Bo'orču, Boroqul and Čila'un, together with the Dörben Noqas (four dogs), J̌ebe, Sube'etai, J̌elme and Qubilai, formed the center of the Mongolian military leadership and administration around Genghis Khan. When the Chinese diplomat Zhao Hong visited the Mongols as the Song's ambassador in 1221 , he discovered that, apart from Genghis Khan, no other commander in the Mongol military hierarchy was higher than Muqali.

Muqali was a capable commander who did not lose any of his open field battles. His special abilities included his talent to integrate troops of different ethnicities ( Kitan , Jurchen , Han , Tangut ) into the army and to adapt their military procedures and their war techniques. Like Genghis Khan, he promoted officers on the basis of skill and loyalty, not relationships or bloodlines. For example, he made Shih T'ien-ni and Shih T'ien-hsiang, two Chinese brothers who had previously been enemies of the Mongols, his highest-ranking subordinates. At times, Muqali showed himself to be extremely generous towards defeated enemy troops, but like other Mongol military leaders he did not shy away from carrying out rampant massacres of the civilian population.

The Union of the Mongolian Tribes (1199-1211)

The first military enterprise, in connection with which Muqali is mentioned in the sources, probably took place in 1199. Temüdschin's ally and mentor To'oril, the Ong Khan of the Kereyit , had got into trouble during a dispute with the Naiman . Temüdschin sent him Muqali, Bo'orču, Boroqul and Čila'un to help. The Dörben Kulu'ud managed to put the Naiman to flight and to save To'oril and his people.

In the dispute for supremacy over the Mongolian steppe, Muqali took part in other decisive battles. In 1202 he was probably involved in Temüdschin's battle against the Tatars , the tribe whose warriors had killed Temüdschin's father. After the battle, all male Tatars that towered over a chariot axle were killed.

Temüdschin and the Ong Khan To'oril fell apart and in 1203 there were open hostilities. A battle broke out between Temüdschin's troops and the Kereyit. On the third and final day of the battle, Muqali and a squad of hand-picked warriors stormed Ong Khan's camp, ending the battle.

Another decisive battle in which Muqali took part at the time of the founding of the empire occurred in 1204. Fled warriors of the tribes subjugated by Tenmüdschin, including the Tayiči'ut, Tatar, Kereyit and Merkit , had rallied around Tayang Khan from the Naiman. The Naiman and their allies were the last power that still represented a threat to Temüdschin's claims to rule over the steppe. The coalition suffered a devastating defeat and resistance to Temüdschin's rise was broken. In 1206 a Qurultai (large council of the Mongol princes and military leaders) took place and Temüdschin was appointed ruler of the peoples of the steppe and received the title of Činggis Qan.

There is no further information about Muqali's whereabouts in the years 1206 to 1211. However, it is very likely that he took part in Genghis Khan's campaign against the Tangut Xi Xia dynasty in northern China from 1209 to 1210.

The campaign against the Jin (1211-1216)

In 1211, Genghis Khan declared war on the Jin Dynasty in northern China. The Mongol army moved south across the Gobi desert and reached Jin territory in the spring. Initially, Muqalis left wing troops moved with the main army under Genghis Khan. Various fortresses on the Jin northern border fell in rapid succession. In September 1211 the strategically important battle of Yehuling took place . At the head of a troop of elite troops, Muqali at Huan'erzui succeeded in breaking the ranks of the Jin and thus sealing the defeat of the Jin.

In November 1213, Muqali took the city of Zhuozhou and in the following month or early 1214 the city of Mizhou, whose population he massacred. During the siege of Zhongdu (now part of Beijing), the capital of the Jin, in 1214, Genghis Khan dispatched Muqali to the northeast to subdue Manchuria , the ancestral land of the Jurchen. Cities like Gaozhou, Yizhou, Shunzhou and others fell in quick succession. At the beginning of 1215, Muqali approached the "northern capital" of the Jin, Bejing (today: Liaoyang ; not to be confused with today's Beijing) from the south . The Jin had gathered a sizeable garrison there. The Jin troops advanced against the Mongols and a battle ensued, which ended with a crushing defeat for the Jin. Beijing fell after a long siege in May 1215. Muqali moved with his troops to Xingzhou, defeated another Jin army and took this city as well.

Zhongdu fell in the summer of 1215. Large parts of the northern Jin territory were in Mongolian hands. The emperor had withdrawn to Kaifeng in 1214 to organize resistance from there. Genghis Khan returned to Mongolia with a large part of the Mongol troops and left the consolidation of the conquered areas and the further military operations to generals like Muqali and Samuqa, whom he left with the left wing of the army in northern China. Muqali continued to conquer Liaoning Province , winning five battles and taking a number of cities such as Jinzhou and Guangning, with great civil casualties. In the autumn of 1216 Liaoning was finally subjected and Muqali first followed Genghis Khan to Mongolia.

Regency in Northern China (1217-1223)

Muqali reached Genghis Khan's camp on Kelüren in 1217 and received the highest honors there. Not only did the Khan give him the titles Gui Ong (roughly: state prince) and Taiši (roughly: great teacher), but he also presented him with a duplicate of his own white, nine-tailed standard, which was the highest symbol of his power. With this gesture Genghis Khan placed Muqali in rank above all other Mongolian officers and officials and in principle gave him the same power of disposal over the Mongolian troops that he himself had. Genghis Khan could not give a higher distinction and Muqali was the only Mongol who ever received it from him. Genghis Khan also awarded Muqali all areas south of the Taihangshan and made him commander in chief of all troops in China.

Muqali returned to China and with the north of the Jin territory secured, he now focused his attention on central China. There, too, he quickly took cities such as Suicheng, Lizhou or Zongshan, before Zhending , a central bulwark of the Jin defense, fell in the fall of 1218 . Various cities of Muqali then surrendered without a fight.

He went to Zongdu from where he coordinated the administrative management of the occupied territories and the other military operations in the following years. He waged a brutal but effective war and brought the provinces of Shanxi (1219), Hebei (1220) and Shandong (1222) largely under his control. In negotiations with the South Chinese Song, he also proved to be a skilled diplomat. He continued to prepare offensives, but due to his limited troop strength - most of the Mongolian army was tied up in Central Asia in the war against the Khorezmian Empire (1219-1224) - he did not succeed in achieving further decisive successes.

Death and legacy

Muqali died unexpectedly of an illness in 1223.

After his death, his title and position passed to his son Bōl. However, like other Mongolian military leaders, Bōl was unable to build on his father's successes. The conquest of the Jin Dynasty practically came to a standstill for around a decade before Ögedei Khan , Tolui and Sube'etai resumed the offensive in the early 1230s and the Jin finally went under in 1234. Muqali's grandchildren and great-grandchildren such as Tas, An T'ung or Baiju later held important posts in the Yuan dynasty of Kublai Khan and the Ilkhanate of Hulegu Khan .

Muqali remains a popular figure in Mongolian lore and literature to this day. There he is often portrayed as an almost superhuman superhero.

Bronze statues of Muqali and Bo'orču now flank the Genghis Khan statue on Süchbaatar Square (formerly Genghis Khan Square) in Ulaanbaatar.

Remarks

- ↑ There is no uniform system for transliterating proper names and place names from the time of the Mongol Empire. Accordingly, there are different spellings of the name Muqalis (Muchali, Mukhali, Muquli, Muchuli) in the publications on the topic. In the spelling of Muqali , as with the spelling of other Mongolian names and designations, we follow Manfred Taube's translation of the Secret History of the Mongols (Kiepenheuer, Leipzig and Weimar, 1989), provided that there are no standardized spellings in German, as in the case of Činggis Qans .

- ↑ The Mongols did not orient their geographical ideas to the north, but oriented themselves to China in the south. That is why the left army divisions operated in the east of the west, but the right troops in the west .

Literature (selection)

Historical sources

Secret history of the Mongols

- Manfred Taube: Secret History of the Mongols. Origin, life and rise of Cinggis Qans . Kiepenheuer, Leipzig and Weimar, 1989, ISBN 3-378-00297-2 .

- Igor de Rachewiltz: The Secret History of the Mongols: A Mongolian Epic Chronicle of the Thirteenth Century . 2 volumes. Brill, Leiden 2004, ISBN 978-90-04-15364-6 (English). Online version , abbreviated in the notes, edited by John Street , University of Wisconsin, Madison 2015.

Rasheed ad-Din

- Rashiduddin Fazlullah: Jamiʼuʼt-tawarikh. Compendium of Chronicles - A history of the Mongols . Translation and annotations by Wheeler McIntosh Thackston. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1998 (English).

Yuan shi

- FEA Krause: Cingis Han - The story of his life after the Chinese imperial annals . Karl Winters, Heidelberg, 1922. (German translation of the biography of Genghis Khan from the first Juǎn (chapter) of the Yuan shi.)

- 元史: 卷 一百 十九 列傳 第六: 木華黎 Yuan shi: Juǎn 119, sixth biography: Mùhuálí. Online version of the Chinese text, not translated into Western languages.

Secondary literature

- Erich Haenisch: The last campaigns of Cinggis Han and his death according to the East Asian tradition . In: Bruno Schindler (Ed.): Asia Major . Vol. 9, Leipzig, 1933.

- Luc Kwanten: The Career of Muqali: A Reassessmet . In: Bulletin of Sung and Yuan Studies , No. 14. Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies, Berkeley, 1978, pp. 31-38.

- H. Desmond Martin: Chinghiz Khan's First Invasion of the Chin Empire. In: The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain, No. 2. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1943, pp. 182-216 (English).

- H. Desmond Martin: The Rise of Chingis Khan and his Conquest of North China . Rainbow Bridge, Taipei 1971 (English).

- Timothy May: The Mongol Empire . Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2018, ISBN 978-0-748-64236-6 (English).

- Timothy May: The Mongol Art of War . Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2007, ISBN 978-1-594-16046-2 (English).

- Pow, Stephen: The Last Campaign and Death of Jebe Noyan . In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Vol. 27, No. 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2017 (English).

- Igor de Rachewiltz: Muqali, Bòl, Tas and An-t'ung . In: Igor de Rachewiltz et al. (Ed.): In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yuan Period 1200-1300 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, pp. 3-12.

- Paul Ratchnevsky: Činggis-Khan - His life and work . Steiner, Wiesbaden, 1983.

- Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei . Helion, Solihull 2017, ISBN 978-1-910777-71-8 (English).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei . Helion, Solihull, 2017, p. 34 (English).

- ↑ a b Luc Kwanten: The Career of Muqali: A Reassessmet . In: Bulletin of Sung and Yuan Studies , No. 14. Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies, Berkeley, 1978, pp. 31-32 (English).

- ↑ Christopher P. Atwood: Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire . Facts on Files, New York 2004, pp. 392-393 (English); Timothy May: The Mongol Art of War . Pen and Sword, Barnsley, 2007, pp. 96-97 (English).

-

↑ Luc Kwanten: The Career of Muqali: A Reassessmet . In: Bulletin of Sung and Yuan Studies , No. 14. Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies, Berkeley, 1978, pp. 31-38 (English); H. Desmond Martin: Muqali. In: Ders .: The Rise of Chingis Khan and his Conquest of North China . Rainbow Bridge, Taipei 1971, pp. 239-282 (English); Igor de Rachewiltz: Muqali, Bòl, Tas and An-t'ung . In: Igor de Rachewiltz et al. (Ed.): In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yuan Period 1200-1300 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, pp. 3-12 (English).

- ^ H. Desmond Martin: The Rise of Chingis Khan and his Conquest of North China . Rainbow Bridge, Taipei 1971, p. 66 (English).

- ↑ Igor de Rachewiltz: Muqali, Bol, Tas and An-t'ung . In: Igor de Rachewiltz et al. (Ed.): In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yuan Period 1200-1300 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, pp. 3, 8 (English).

- ↑ Manfred Taube: Secret history of the Mongols. Origin, life and rise of Cinggis Qans . Kiepenheuer, Leipzig and Weimar, 1989, p. 65.

- ↑ Christopher P. Atwood: Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire . Facts on Files, New York 2004, p. 393 (English).

- ↑ Manfred Taube: Secret history of the Mongols. Origin, life and rise of Cinggis Qans . Kiepenheuer, Leipzig and Weimar, 1989, pp. 142, 146.

- ↑ Stephen Pow: The Last Campaign and Death of Jebe Noyan . In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Vol. 27 No. 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2017, p. 3 (English).

- ↑ Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei . Helion, Solihull, 2017, pp. 33–34 (English).

- ^ H. Desmond Martin: The Rise of Chingis Khan and his Conquest of North China . Rainbow Bridge, Taipei 1971, p. 43 (English).

- ↑ Christopher P. Atwood: Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire . Facts on Files, New York 2004, p. 393 (English).

- ↑ FEA Krause: Cingis Han - The story of his life after the Chinese imperial annals . Karl Winters, Heidelberg, 1922, p. 17; Manfred Taube: Secret History of the Mongols. Origin, life and rise of Cinggis Qans . Kiepenheuer, Leipzig and Weimar, 1989, p. 86.

- ↑ Igor de Rachewiltz: Muqali, Bol, Tas and An-t'ung . In: Igor de Rachewiltz et al. (Ed.): In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yuan Period 1200-1300 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, p. 3 (English).

- ↑ Manfred Taube: Secret history of the Mongols. Origin, life and rise of Cinggis Qans . Kiepenheuer, Leipzig and Weimar, 1989, p. 82.

- ↑ a b c Igor de Rachewiltz: Muqali, Bòl, Tas and An-t'ung . In: Igor de Rachewiltz et al. (Ed.): In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yuan Period 1200-1300 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, p. 4 (English).

- ↑ Manfred Taube: Secret history of the Mongols. Origin, life and rise of Cinggis Qans . Kiepenheuer, Leipzig and Weimar, 1989, p. 136.

- ^ H. Desmond Martin: The Rise of Chingis Khan and his Conquest of North China . Rainbow Bridge, Taipei 1971, pp. 141, 336 (English); Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei . Helion, Solihull, 2017, p. 106 (English).

- ^ H. Desmond Martin: The Rise of Chingis Khan and his Conquest of North China . Rainbow Bridge, Taipei 1971, pp. 163, 166 (English); Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei . Helion, Solihull, 2017, pp. 121-122 (English).

- ↑ Paul Ratchnevsky: Chinggis Khan - His life and work . Steiner, Wiesbaden, 1983, pp. 103-104; Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei . Helion, Solihull, 2017, p. 122 (English); Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei . Helion, Solihull, 2017, p. 122 (English).

- ↑ Igor de Rachewiltz: Muqali, Bol, Tas and An-t'ung . In: Igor de Rachewiltz et al. (Ed.): In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yuan Period 1200-1300 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, p. 5 (English); Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei . Helion, Solihull, 2017, pp. 128, 130 (English).

- ↑ Igor de Rachewiltz: Muqali, Bol, Tas and An-t'ung . In: Igor de Rachewiltz et al. (Ed.): In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yuan Period 1200-1300 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, p. 5 (English).

- ↑ Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei . Helion, Solihull, 2017, p. 131 (English).

- ↑ a b Christopher P. Atwood: Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire . Facts on Files, New York 2004, p. 393 (English); Igor de Rachewiltz: Muqali, Bòl, Tas and An-t'ung . In: Igor de Rachewiltz et al. (Ed.): In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yuan Period 1200-1300 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, p. 6 (English).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Muqali |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Mongolian general |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1180 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mongolia |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1223 |

| Place of death | China |