Sube'etai

Sube'etai or Subutai ( Central Mongolian : ᠰᠦᠪᠦᠭᠠᠲᠠᠢ , Sube'etai; Mongolian (modern) : Сүбээдэй, Sübeedei; Chinese : 速 不 台, Subutai; * around 1175 in Mongolia ; † 1248 in Mongolia) was a general and general in of the Army of the Mongol Empire . Sube'etai was nicknamed Ba'atur (Middle Mongolian: ᠪᠠᠭᠠᠲᠤᠷ , Ba'atur; Mongolian (modern): Баатар, Baatar; literally: hero), an honorary title that is comparable to the European knight. He is not only regarded as the most capable general of Genghis Khan , Ögedei Khan and Güyük Khan , today's military historians count him among the greatest military leaders in history and see him on a par with Napoleon , Alexander , Caesar and Hannibal . However, this rating is not without controversy, some authors see him as just one of many Mongolian military leaders.

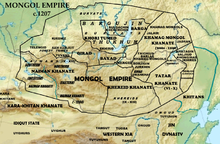

It is undisputed that Sube'etai was involved in the capture of more territory than any other historical military leader in the course of his 50-year career. His area of operation extended from the forests of Siberia in the north to Iran in the south, from China in the east to Hungary in the west. Troops under his command penetrated as far as Poland, Austria and the Adriatic. Atrocities of war and massacres of civilians were a routine part of his operations, and some cities were so thoroughly razed and depopulated on his orders that they were never rebuilt.

Life

The sources on the person Sube'etais are extremely sketchy, contradicting and opaque. Accordingly, a lot of information about his biography, his origins and early years is controversial in the secondary literature. For example, the year and place of his birth, his ethnic affiliation, his family circumstances, as well as the dating of decisive events, such as his affiliation with Genghis Khan or his first independent command, are discussed.

In addition, there is a certain mythologization in the secondary and popular literature, many of the statements made there cannot be substantiated on the basis of the primary sources or proven to be false. Some of these statements are widespread and widely cited both in the literature and, above all, on the Internet. One of the most popular is that which says that Sube'etai "fought 65 open field battles and subdued 32 nations". This statement, which apparently found its way from Basil Liddel-Hart into Richard A. Gabriel's biography Subotai the Valiant , and from there to the English-language Wikipedia, is not documented in any of the secondary sources citing it. Carl Sverdrup has worked out the most precise analysis of the primary sources for this information so far and came up with 35 battles that Sube'etai fought. Other popular examples that cannot be substantiated by the primary sources include the statements that Sube'etai never lost a battle; Sube'etai was not an ethnic Mongol or steppe nomad, but was one of the forest inhabitants of southern Siberia; Sube'etai was so obese that no horse could carry him and he had to drive around in an iron cart; Sube'etai was one-eyed and had a crippled hand. The list could be expanded to include numerous examples. Stephen Pow and Jingjing Liao published a first text in 2018 to counteract these mythologizations and legends, and to encourage them to come to terms with them.

Origin and early years

The main historical sources for information on Sube'etai's ancestry, early years of life and first years of his career, which are available in Western translations, are the Secret History of the Mongols and in particular the Chinese Chronicle Yuan Shi , which contains a brief biography of Sube'etai . Persian and European sources provide poor, if any, information. The Persian chronicler Raschīd ad-Dīn is an exception , who in his work Jāmiʿ at-tawārīch gives some information about Sube'etai's tribe, the Uriyangqay, and his family.

None of the historical sources give the exact year of Sube'etais birth. Only the Yuan shi gives a clue. According to this source, he died in a mouse year (Wu-Shen) at the age of 73. Since the mentioned Chinese year extended from January 28, 1248 to January 15, 1249 of the Western calendar, his birth can be dated to 1175 or 1176.

There is relative agreement in the sources that Sube'etai belonged to a tribe called Uriyangqay (Uriyangkhai, Uriangqan, Uriankhit, Uriyangqat). None of the primary sources indicate that the Uriyangqay were not ethnic Mongols. On the contrary, both the Yuan shi and Rashīd ad-Dīn clearly state that they were a Mongolian tribe. They lived west of the Onon River in what is now Mongolia. According to Rashīd ad-Dīn there was another tribe called Uriyangqai, they lived west of Lake Baikal in southern Siberia, but were not related to the tribe from which Sube'etai came.

Particularly with regard to Sube'etai's family, not only the information in today's secondary literature, but also those in historical sources are inconsistent and contradictory. The most detailed and probably most reliable information can be found in the Yuan shi . According to this source, Sube'etai's father was named Qaban and he had an older brother named Huluhun. The historical sources are silent about Sube'etai's mother and any other siblings. Also, next to nothing is known about Sube'etai's women. Only from Tumeken, imperial princess of the Genghisid family (Temüdschin's family and descendants), whom Ögedei Khan gave him as his wife in 1229, the name has been passed down. Sube'etai had at least two sons, Uriyangqadai and Kököcü, and one grandson, Aju. Uriyangqadai and Aju were also important army leaders under Möngke Khan and Kublai Khan . The Mongol Secret History According Sube'etai was a close relative of the Jelme. This was also an important general of Genghis Khan and one of his earliest followers.

It is not known exactly when the paths of Sube'etai and Temüdschin first crossed. If you follow the description in the Secret History , a connection around 1190 seems likely. However, the information from the Yuan shi can be interpreted to the effect that this did not happen until 1203. There is no further information about the intervening time, and there is also an almost ten-year gap in the biography of Genghis Khan during this period.

Military operations

Sube'etai's first military ventures are also poorly documented in the primary sources, but the source situation becomes clearer and more unambiguous after around 1219, as the number of sources increases.

Sube'etai belonged to the top level of command of the Mongol Empire early on. Already in 1206, on the occasion of his enthronement of Genghis Khan , had Temüdschin him as one of Dörben Noqas appointed (four dogs) to one of its most important military leaders. The Dörben Noqas , Sube'etai, J̌elme, J̌ebe and Qubilai were the commanders of the Mongol vanguard and together with the Dörben Kulu'ud (four horses) Muqali , Bo'orču, Boroqul and Čila'un, the center of the Mongolian military leadership around Genghis Khan.

The first mention of Sube'etai's military ventures is in the Secret History. Accordingly, in 1204 he commanded part of the vanguard of Genghis Khan's campaign against the Naimans under Tayang Khan.

In 1211, Genghis Khan launched his first campaign against the Jin Dynasty in northern China. In addition to Jebe Noyan, who presumably reports to him, Sube'etai commanded a wing of the army. They conquered parts of Manchuria, then advanced south, where they united with the other parts of the Mongol army and in 1214 advanced against the capital of the Jin, Zhōngdū (today's Beijing), and besieged them. Since the Mongols had in principle subjugated the Jin and made rich booty, and diseases were also spreading in their camps, they temporarily negotiated a peace treaty with the Jin and returned to Mongolia. According to the Yuan shi , Sube'etai was the first to storm the walls of the city of Huanzhou in 1212 and was richly rewarded by Genghis Khan for this.

Sube'etai's first command: The annihilation of the Merkit (1216–1218?)

Sube'etai received his first independent command when he was sent by Genghis Khan to ultimately crush the Merkites . In 1208, after several defeats against Genghis Khan's warriors, they withdrew to the west of what is now Kazakhstan. The question of when Sube'etai received this commission is lively debated in today's literature, as there is extreme confusion in the primary sources. Paul Buell and Christopher Atwood have devoted detailed articles to the early Mongolian campaigns in the west, which included Sube'etai's first command. The majority of academic authors date from 1216 or 1217, for example Atwood, Igor de Rachewiltz, Paul Ratchnevsky and Carl Sverdrup.The sources are inconsistent not only with regard to the dating, but also with regard to other details of the campaign, such as the number of battles and the locations in which they took place. It is certain that Sube'etai followed the Merkites, tracked them down and, presumably in 1218, inflicted a devastating defeat on them. After the death of their last leader Qudu, the Merkite tribe ceased to exist as an independent entity.

Immediately after this battle there was a first encounter between the Mongols and troops of the Khorezmian Empire . There was a battle, presumably on the Irgis , which neither side could win and both armies took up camp at nightfall. According to the Chinese sources, the Khorezm Shah Muhammad II withdrew with his troops that night, according to Persian sources it was Sube'etai who left the battlefield with his troops. The first battle brought no decision, but it did open up the conflict between the two empires that ultimately led to the downfall of Khorezmia.

The conquest of Khorezmia and the hunt for Shah Muhammad II (1218–1220)

Also in 1218 there were further diplomatic entanglements, which finally caused Genghis Khan to undertake a large-scale campaign against Khorezmia. The invasion of Khoresmia began in 1219, Sube'etai commanded one of the divisions of the vanguard. A year later, several armies of Khorezmia were defeated and important cities were taken. The Chorzmic resistance collapsed and Shah Muhammad II fled to the west. Sube'etai and J̌ebe Noyan were assigned to persecute the Shah. They chased him relentlessly after up to Khorasan and Masanderan , in the area of present-day Iran, beat several victorious battles and laid several cities in ruins. Sube'etai succeeded in stealing the state treasure and the harem of the Shah. For this he was expressly honored by Genghis Khan. The Shah ultimately fled to an island in the Caspian Sea , where he died exhausted and lonely at the end of 1220.

Circumnavigation of the Caspian Sea (1221–1224)

After completing their mission, Sube'etai and J̌ebe did not return east. Genghis Khan followed a suggestion made by Sube'etai and sent them north to explore the areas west of the Caspian Sea. The hunt for Muhammad II and the subsequent mission around the Caspian Sea, often referred to in literature as The Great Raid , is, in the opinion of many contemporary authors, an extraordinary military achievement that “does not appear in the annals of war Finds parallel “(Carl Sverdrup). In four years the Mongols covered several thousand kilometers, overran ten states or tribal associations, fought more than a dozen victorious battles and destroyed numerous cities, most of the time carrying out rampant massacres of the civilian population.

The Mongols devastated large parts of Azerbaijan and Arrāns and crossed Georgia , where they defeated an army under Giorgi IV Lascha in 1221 . Sube'etai and J̌ebe moved north via Derbent , crossed the Caucasus and defeated an army of Kipchaks and Alans on its north side that had been waiting for them there. Parts of the surviving Kipchaks under Kötan Khan fled to the Rus area . After a detour to the Crimea, where they burned down the important trading center Sudak , the Mongols followed the Kipchaks into the Rus area. A coalition of Kipchaks and troops from the various principalities of the Rus opposed them and the famous battle of the Kalka took place . J̌ebe Noyan was probably captured and killed by the Kipchaks in the run-up to the battle. Sube'etai defeated the alliance, but did not pursue the refugees, but moved east to return to Mongolia. The Mongols crossed the territory of the Volga-Bulgarians , where they were surprised by an army of the Bulgarians and Sube'etai's troops suffered a defeat for the first time.

The annihilation of the Xi Xia (1226-1228)

The next campaign of Genghis Khan was directed against the dynasty Xi Xia of Tanguts . Sube'etai was given command of a wing of the Mongol armed forces, penetrated from the west into the Tangut area and overpowered the defensive positions there. Sube'etai's troops joined those Genghis Khan on the Yellow River . The Mongol armed forces met and defeated the main Tangut army. Shortly afterwards, Genghis Khan died in August 1227. Sube'etai probably stayed in northern China until 1228, where he fought the remnants of the Tangut armed forces. On the occasion of the enthronement of Ögedei Khan in 1229, he returned to Mongolia.

Campaign against the Kipchaks under Bachman (1229–1230?)

The chronology of the events that directly followed Ögedei's enthronement is given in contradictory terms in the primary sources. Ögedei again sent Sube'etai far to the west. The aim of the mission was the suppression of a strong association of Kipchaks under the leadership of Bachman, who threatened the western border of the Mongolian Empire. Carl Sverdrup interprets the information Raschīd ad-Dīns and those of the Secret History to the effect that he dates the campaign to 1229-1230. Paul Buell, on the other hand, follows the information given by Yuan shi and locates the campaign at the beginning of the great western campaign 1236-1237. There is agreement in the sources about the course of the campaign. Sube'etai captured the Kipchaks on the Volga and defeated them, but Bachman managed to escape. The Mongols followed him and a detachment led by Genghis Khan's grandson Möngke managed to get hold of Bachman and kill him.

The Annihilation of the Jin (1230-1234)

The first great campaign of the Mongols under Ögedei Khan was directed against the Jin dynasty. In several columns, the Mongolian troops advanced into the Jin area in order to destroy them once and for all. Sube'etai's first assignment turned out to be a failure. The Mongols under the commandant Doqolqu Čerbi did not succeed in overcoming the central defensive position of the Jin at the Tong Pass. Ögedai sent Sube'etai to assist Doqolqu. Sube'etai's troops, however, were defeated by the Jin not far from present-day Xi'an , and the Mongols broke off their attacks on the Tong Pass.

Sube'etai now put a daring plan into action. He crossed several hundred kilometers of enemy Song Dynasty territory to advance into Jin territory from the southwest. This train lasted several months and there were several battles against the Song, which the Mongols were able to win for themselves. The Song entered into negotiations with the Mongols and eventually gave them free passage through their territory. The Mongol march had not gone unnoticed by the Jin, and when Sube'etai's troops reached the Jin area, the main Jin force under General Wanyan Heda awaited them there. In January 1232 they met for the first time and the Mongols withdrew under cover of night. Since the Jin had moved troops from the north to the south to oppose Sube'etai, the main Mongolian army under Ögedei succeeded in defeating the Chinese troops in the north, crossing the Yellow River and sending reinforcements to Sube'etai. When they arrived, Sube'etai opened an attack on Vanyan Heda's troops on February 9 and defeated them.

As the Jin military forces were largely defeated, Ögedai Khan returned to Mongolia in April 1232 and left Sube'etai in command. From 1232 to 1233 he besieged Kaifeng , the capital of the Jin, who fell in May 1233. Aizong, the Emperor of the Jin, fled to Caizhou , but his situation was so hopeless that he took his own life there on February 9, 1234. The Jin Dynasty ceased to exist. Since the city of Kaifeng, already then a metropolis of millions, had offered such bitter resistance, Sube'etai intended to wipe out the entire population of the city, as he usually did when cities did not voluntarily submit to him. Only a direct order from Ögedei Khan could ultimately prevent him.

The Great Western Campaign (1236-1242)

In 1236 Ögedai sent Sube'etai west again to support Batu Khan , grandson of Genghis Khan and heir of the western regions of the empire, in expanding west. These ventures culminated in the invasion and devastation of Eastern Europe, the so-called Mongol storm . In today's literature there is great agreement that the Western campaign was nominally under the command of Batus, but Sube'etai was de facto in command of the supreme command and was responsible for strategic planning. The Yuan shi quotes Batu as saying: "All the successes we achieved at that time we owe Sube'etai".

In the winter of 1236-1237 Sube'etai defeated the Volga-Bulgarians and conquered their territory. The Mongols moved further west and advanced with three columns into the principalities of the Rus. Several armies of the Rus were defeated in quick succession and numerous cities were taken and devastated. The principalities of Ryazan , Vladimir-Suzdal and parts of Chernigov were conquered. The Mongols spent the summer on the Don and smaller army divisions subjugated the tribes on the plains around the Black Sea . In 1239 the Mongols continued their attacks against the Rus. The Principality of Chernigov was completely captured, as was Halych-Volodymyr . Kiev , Vladimir and other cities fell in quick succession in 1240.

In 1241 the Mongols advanced in several columns into Poland and Hungary. With what unprecedented precision Sube'etai the enterprises of various army divisions tuned to each other, proves itself in April 1241, when the Mongols Polish and German forces in the Battle of Legnica defeated, and only two days later the Hungarian army under King Bela IV. In the battle of Muhi . The Mongols remained in Hungary for the rest of the year, a smaller army detachment pursued Bela IV as far as the Adriatic Sea, and another advanced to Wiener Neustadt .

Completely surprising for the attacked Eastern Europeans, the Mongols withdrew to the east in 1242. The reasons for this are controversial in today's literature. Ögedei Khan died in December 1241, and the most obvious explanation for the withdrawal may be that the princes and military leaders had to return to Mongolia to participate in the election of a new Khan.

Last years and death

His last campaign led Sube'etai 1245-1246 to southern China, where he fought against the Song.

When the Franciscan Carpini stayed at the court of Ögödei's successor Güyük in 1247, Sube'etai also stayed there. Carpini reports that Sube'etai was known among the Mongols as the "Great Soldier".

Sube'etai died in Mongolia in 1248. He had received his first command at a Qurultai (council of the Mongol princes and military leaders) on the Tuul and there he was probably buried.

Remarks

- ↑ There is no uniform system for transliterating proper names and place names from Central Mongolian from the time of the Mongol Empire. Accordingly, numerous different spellings of the name Sube'etai Ba'aturs can be found in the publications on the topic. We follow the spelling Sube'etei Ba'atur . This translation of the Central Mongolian spelling is mainly used by Mongolists and philologists in the German-speaking area (Haenisch, 1948; Heissig, 1985; Leicht, 1985; Weiers, 1996; in the English-speaking area: Sübe'etai). Various authors prefer the translation of the Chinese spelling, Subutai. This has established itself as the most widespread today, probably not least because it is keyboard and pronunciation friendly.

- ↑ The information given in the following sections is documented relatively uniformly in the primary sources from around 1219 onwards. They can be found almost identically in different texts of the secondary literature. Unless otherwise stated, we follow the following texts here: Paul D. Buell: Sübȫtei Ba'atur . In: Igor de Rachewiltz et al. (Ed.): In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yuan Period 1200-1300 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, pp. 13-26 (English); Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: Sübe'etei Ba'atur, Anonymous Strategist . In: Journal of Asian History . No. 47.1. Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 2013, pp. 33–49 (English).

Literature (selection)

Historical sources

Carpini

- Felicitas Schmieder (Ed.): Johannes von Plano Carpini: Customer of the Mongols 1245–1247 . Translated, introduced and explained by Felicitas Schmieder. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1997, ISBN 3-7995-0603-9 .

- Giovanni di Piano Carpini: The Story of the Mongols Whom We Call the Tartars . Translated by Erik Hildinger. Branden Books, Boston 1996, ISBN 978-0828320177 (English).

Carmen Miserabile

- Rogerius of Torre Maggiore: Lament. Translated and with notes by Hansgerd G ِ ckenjan. In: Thomas von Bogyay (ed.): Der Mongolensturm - Reports from eyewitnesses and contemporaries 1235 - 1250. Hungary's historian vol. 3. Styria, Graz 1985, ISBN 978-3222109027 , pp. 139-186

Erdeni-yin Tobči

- Ssanang Ssetsen Chungtaidschi: History of the Eastern Mongols and their Princely House . Translation and comments by Isaak Jakob Schmidt . St. Petersburg, 1829. Online . (Contains the text in Mongolian script and in German translation.)

- Sagang Sečen: History of the Mongols and their Princely House . Manesse Verlag, Munich, 1985. (A reprint of the translation by Isaak Jakob Schmidt. Revised, edited and with an afterword by Walther Heissig.)

Galician-Volhyn Chronicle

- Anonymous: Galician-Volynian Chronicle . Translated and commented by George A. Perfecky. Willhelm Fink Verlag, Munich 1973. Online .

Secret history of the Mongols

- Erich Haenisch : The Secret History of the Mongols. From a Mongolian record from 1240 from the island of Kode'e in the Keluren River . Harrassowitz, Leipzig 1948.

- Manfred Taube: Secret History of the Mongols. Origin, life and rise of Cinggis Qans . Kiepenheuer, Leipzig and Weimar, 1989, ISBN 3-378-00297-2

- Francis Woodman Cleaves: The Secret History of the Mongols . Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1982, ISBN 978-0-674-79670-6 . Online .

- Igor de Rachewiltz: The Secret History of the Mongols: A Mongolian Epic Chronicle of the Thirteenth Century . 2 volumes. Brill, Leiden 2004, ISBN 978-90-04-15364-6 . Version abridged and edited by John Street, University of Wisconsin, Madison 2015 Online .

Ibn al-Athīr

- Ibn al-Athir: The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from al-Kamil fi'l-Ta'rikh. Part 3: The Years 589-629 / 1193-1231: The Ayyubids after Saladin and the Mongol Menace . Translated by DS Richards. Routledge, New York 2010, ISBN 978-0754669524 (English)

Juvaini

- Ata-Malik Juvaini: Genghis Khan. The History of the World Conqueror . Translated by John Andrew Boyle. Manchester University Press, Manchester 1997, ISBN 978-0295976549 (English) online .

Kartlis Tskhovreb

- Anonymous: The Hundred Years' Chronicle . Translated and commented by Dmitri Gamq'relidze. In: Stephen Jones (ed.): Kartlis Tskhovreba - A History of Georgia . Artanuji, Tbilisi 2014 Online .

Kirakos Ganjakets'i

- Kirakos Ganjakets'i: History of the Armenians . Translated and commented by Robert Bedrosian. Sources of the Armenian Tradition, New York 1986 Online .

Rasheed ad-Din

- Raschīd ad-Dīn: The Successors of Genghis Khan . Translated by John Andrew Boyle . Columbia University Press, New York 1971, ISBN 978-0231033510 (English) online .

- Rashiduddin Fazlullah: Jamiʼuʼt-tawarikh. Compendium of Chronicles - A history of the Mongols . Translation and annotations by Wheeler McIntosh Thackston. Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1998

Yuan shi

- Paul D. Buell: The Biography of Sübedei . In: Readings on Central Asian History . East Asian Studies 210: Nomads of Eurasia. Independent Learning, Bellingham 2003, pp. 96-107 (English). Online . (Contains a translation of the Sube'edai biography from chapter 121 of the Yuan shi .)

- Stephen Pow and Jingjing Liao: Subutai: Sorting Fact from Fiction Surrounding the Mongol Empire's Greatest General . In: Journal of Chinese Military History . No. 7 . Brill, 2018, ISSN 2212-7445 , p. 37-76 (English). (Contains a translation of the two Sube'edai biographies from chapters 121 and 122 of the Yuan shi .)

Secondary literature

Monographs, biographies

- Richard A. Gabriel: Subotai the Valiant - Genghis Khan's Greatest General . Preager, Westport, Connecticut 2004, ISBN 978-0-8061-3734-6 (English).

- Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei . Helion, Solihull 2017, ISBN 978-1-910777-71-8 (English).

Short biographies and biographical articles

- Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat : Souboutaï, général Mongol . In: Nouveaux Mélanges Asiatiques . tape 2 . Dondey-Dupré, Paris 1829, p. 89-97 (French). Online .

- Christopher P. Atwood: Sübe'etei Ba'atur . In: Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire . Facts on Files, New York 2004, ISBN 978-1-4381-2922-8 , pp. 520-521 (English).

- Paul D. Buell: Sübȫtei Ba'atur . In: Igor de Rachewiltz et al. (Ed.): In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yuan Period 1200-1300 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, ISBN 978-3-447-06948-9 , pp. 13-26 (English).

- Paul D. Buell: The Biography of Sübedei In: Readings on Central Asian History , East Asian Studies 210: Nomads of Eurasia. Independent Learning, Bellingham 2003a pp. 96-107 (English). Online .

- Paul D. Buell: Sübe'etei Ba'atur . In: Historical Dictionary of the Mongol World Empire . Scarecrow Press, Lanham and Oxford 2003b, ISBN 978-0810845718 , pp. 255-258 (English).

- Jack Coggins: Subotai . In: Soldiers and Warriors - An Illustrated History . Courier Corporation, Mineola 2006, ISBN 978-0-486-45257-9 , pp. 127-130 (English).

- Joseph Cummins: Subotai the Valiant: Genghis Khan's Greatest Strategist . In: History's Great Untold Stories: Obscure Events of Lasting Importance . Murdoch, Millers Point 2006, ISBN 978-1-74045-808-5 , pp. 32-58 (English).

- Paul K. Davis: The Two-Headed General: Chinggis Khan and Subedei . In: Masters of the Battlefield - Great Commanders from the Classical Age to the Napoleon Era . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-534235-2 , pp. 173-215 (English).

- Basil Liddell Hart : Jenghiz Khan and Sabutai . In: Great Captains Unveiled . Blackwood & Sons, Edinburgh and London 1927, pp. 1-35 (English). Online . German edition: Grosse Heerführer . Econ Verlag, Düsseldorf 1968

- Timothy May: Sübedei Ba'atar . In: Donald Ostrowski (Ed.): Portraits of Medieval Eastern Europe 900-1400 . Routledge, New York 2018, ISBN 978-1-138-70120-5 , pp. 68-79 (English).

- Stephen Pow and Jingjing Liao: Subutai: Sorting Fact from Fiction Surrounding the Mongol Empire's Greatest General . In: Journal of Chinese Military History . No. 7 . Brill, 2018, ISSN 2212-7445 , p. 37-76 (English).

- Ilja Steffelbauer: The cavalry warrior: Subutai the brave . In: The War: From Troy to the Drone . Brandstätter, Vienna and Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-7106-0069-2 , pp. 113-136 .

- Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: Sübe'etei Ba'atur, Anonymous Strategist . In: Journal of Asian History . No. 47.1 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 2013, p. 33-49 (English).

- Stephen Turnbull : Portrait of a Soldier: Subadai Ba'adur . In: Genghis Khan & the Mongol Conquests 1190-1400 . Osprey, Oxford 2003, ISBN 978-1-4728-1021-2 , pp. 73-76 (English).

Military theoretical treatises

- Jose ZL Andin: Subetei Bagatur: Master of the OODA Loop . BiblioScholar, 2012, ISBN 978-1-288-22873-7 (English).

- Sean Slappy: Command and Control began with Subotai Bahadur, the Thirteens Century Mongol General . United States Marine Corps Command and Staff College, Quantico, Virginia 2010 (English). Master thesis. Online .

further reading

- Christopher P. Atwood: Pu'a's Boast and Doqolqu's Death: Historiography of a Hidden Scandal in the Mongol Conquest of the Jin. In: Journal of Song-Yuan Studies . No. 45 . Society for Song, Yuan, and Conquest Dynasty Studies, 2015, ISSN 1059-3152 (English). Online .

- Christopher P. Atwood: Jochi and the Early Western Campaigns . In: Morris Rossabi (Ed.): How Mongolia Matters: War, Law, and Society . Brill, Leiden 2017, ISBN 978-90-04-34340-5 , pp. 35-56 (English). Online .

- Emil Bretschneider: Mediaeval researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources from the 13th to the 17th century Vol. I. Trübner, London 1888 (English). On-line.

- Paul D. Buell: Early Mongol Expansion in Western Siberia and Turkestan (1207-1219): a Reconstruction . In: Central Asiatic Journal , Vol. 36, No. 1/2. Harrasowitz, Wiesbaden 1992, pp. 1-32 (English).

- Francis Woodman Cleaves: The Historicity of The Baljuna Covenant . In: Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies , Vol. 18, No. 3/4, Harvard-Yenching Institute, Beijing 1955, pp. 357-421 (English).

- René Grousset: L'empire des steppes: Attila, Gengis-Khan, Tamerlan . Editions Payot, Paris 1939, (French). English edition: The Empire of the Steppes . Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick 1970. Translated by Naomi Walford.

- René Grousset: Le conquérant du monde . Albin Michel, Paris 1944 (French). English edition: Conqueror of the World . Orion Press, New York 1966. Translated by Marian McKellar and Denis Sinor.

- Peter Jackson: The Mongols and the West 1221-1410. Routledge, New York, 2014, ISBN 978-0-582-36896-5 (English)

- David Nicolle, Viacheslav Shpakovsky: Kalka River 1223 - Genghiz Khan's Mongols invade Russia . Osprey, Oxford 2001, ISBN 978-1-84176-233-3 (English).

- Paul Ratchnevsky: Ghengis Khan - His Life and Legacy . Blackwell, Oxford and Cambridge 1992, ISBN 978-0-631-16785-3 (English).

- Michael Weiers (Ed.): The Mongols. Contributions to their history and culture . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1996, ISBN 978-3-534-03579-3 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christopher P. Atwood: Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire . Facts on Files Inc, New York, 2004, p. 601 (English).

- ↑ Basil Liddell Hart: Jenghiz Khan and Sabutai. In: Great Captains Unveiled. Blackwood & Sons, Edinburgh and London 1927, p. 3 (English); Richard A. Gabriel: Subotai the Valiant - Genghis Khan's Greatest General . Preager, Westport, Connecticut 2004, S.xi (English).

- ^ Leo de Hartog: Ghengis Khan . Tauris, London, 1989, pp. 165-166 (English); Timothy May: The Mongol Art of War . Pen & Sword, Barnsley, 2007, pp. 93-95 (English).

- ↑ Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: Sübe'etei ba'atur, Anonymous Strategist . In: Journal of Asian History . No. 47.1 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 2013, p. 48 .

- ↑ Basil Liddell Hart: Jenghiz Khan and Sabutai. In: Great Captains Unveiled. Blackwood & Sons, Edinburgh and London 1927, p. 3 (English); Richard A. Gabriel: Subotai the Valiant - Genghis Khan's Greatest General . Preager, Westport, Connecticut 2004, S.xi (English).

- ↑ Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: Sübe'etei ba'atur, Anonymous Strategist . In: Journal of Asian History . No. 47.1. Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 2013, p. 49 (English); Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sube'etei . Helion, Solihull 2017, pp. 359-366 (English).

- ^ Richard A. Gabriel: Subotai the Valiant - Genghis Khan's Greatest General . Preager, Westport, Connecticut, 2004, pp. 1-3.

- ↑ Turnbull, Stephen: Genghis Khan & the Mongol Conquests 1190-1400 . Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2003, p. 73 (English)

- ^ Franklin Mackenzie: Genghis Khan . Scherz, Munich, 1977, p. 116.

- ↑ Stephen Pow and Jingjing Liao: Subutai: Sorting Fact from Fiction Surrounding the Mongol Empire's Greatest General . In: Journal of Chinese Military History . No. 7. Brill, Leiden, 2018, pp. 37-76, (English).

- ^ A b Paul D. Buell: The Biography of Sübedei . In: Readings on Central Asian History. East Asian Studies 210: Nomads of Eurasia. Independent Learning, Bellingham 2003, p. 100 (English).

- ↑ Wheeler McIntosh Thackston: Rashiduddin Fazlullah's Jami'u't-Tawarikh. Compendium of Chronicles - A history of the Mongols . Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1998, pp. 75-77 (English).

- ↑ Stephen Pow and Jingjing Liao: Subutai: Sorting Fact from Fiction Surrounding the Mongol Empire's Greatest General . In: Journal of Chinese Military History . No. 7. Brill, Leiden, 2018, p. 51, (English); Christopher P. Atwood: Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire . Facts on Files Inc., New York 2004, p. 520 (English).

- ↑ Paul D. Buell: The Biography of Sübedei . In: Readings on Central Asian History. East Asian Studies 210: Nomads of Eurasia. Independent Learning, Bellingham 2003, p. 97 (English).

- ↑ Paul D. Buell: The Biography of Sübedei . In: Readings on Central Asian History. East Asian Studies 210: Nomads of Eurasia. Independent Learning, Bellingham 2003, p. 99 (English).

- ↑ Wheeler McIntosh Thackston: Rashiduddin Fazlullah's Jami'u't-Tawarikh. Compendium of Chronicles - A history of the Mongols . Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1998, pp. 77, 420; Raschīd ad-Dīn: The Successors of Genghis Khan . Translated by John Andrew Boyle. Columbia University Press, New York 1971, pp. 248-250 (English); Christopher P. Atwood: Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire . Facts on Files Inc., New York, 2004, p. 6, 592 (English).

- ↑ Manfred Taube: Secret history of the Mongols. Origin, life and rise of Cinggis Qans . Kiepenheuer, Leipzig and Weimar, 1989, pp. 36, 52.

- ↑ Paul D. Buell: Sübȫtei ba'atur . In: Igor de Rachewiltz et al. (Ed.): I n the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yuan Period 1200-1300 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, pp. 13-14 (English); Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: Sübe'etei Ba'atur, Anonymous Strategist . In: Journal of Asian History . No. 47.1. Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 2013, p. 34 (English)

- ↑ Christopher P. Atwood: Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire . Facts on Files Inc., New York, 2004, p. 6, 592 (English).

- ↑ Paul Ratchnevsky: Ghengis Khan - His Life and Legacy . Blackwell, Oxford and Cambridge 1992, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ Manfred Taube: Secret history of the Mongols. Origin, life and rise of Cinggis Qans . Kiepenheuer, Leipzig and Weimar, 1989, p. 146.

- ↑ Manfred Taube: Secret history of the Mongols. Origin, life and rise of Cinggis Qans . CH Beck Verlag, Munich 1989, p. 122.

- ↑ Stephen Pow and Jingjing Liao: Subutai: Sorting Fact from Fiction Surrounding the Mongol Empire's Greatest General . In: Journal of Chinese Military History . No. 7. Brill, Leiden, 2018, p. 52, (English).

- ^ A b Christopher P. Atwood: Jochi and the Early Western Campaigns . In: Morris Rossabi (Ed.): How Mongolia Matters: War, Law, and Society . Brill, Leiden, 2017, pp. 35-56 (English); Paul D. Buell: Early Mongol Expansion in Western Siberia and Turkestan (1207-1219): a Reconstruction . In: Central Asiatic Journal , Vol. 36, No. 1/2. Harrasowitz, Wiesbaden, 1992, pp. 1-32 (English).

- ↑ Christopher P. Atwood: Jochi and the Early Western Campaigns . In: Morris Rossabi (Ed.): How Mongolia Matters: War, Law, and Society . Brill, Leiden, 2017, p. 48 (English); Igor de Rachewiltz: The Secret History of the Mongols: A Mongolian Epic Chronicle of the Thirteenth Century . Brill, Leiden, 2004, p. 735 (English); Paul Ratchnevsky: Ghengis Khan - His Life and Legacy . Blackwell, Oxford and Cambridge, 1992, p. 116 (English); Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sube'etei . Helion, Solihull, 2017, p. 178 (English).

- ↑ Christopher P. Atwood: Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire . Facts on Files, New York 2004, p. 347 (English).

- ↑ Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: Sübe'etei ba'atur, Anonymous Strategist . In: Journal of Asian History . No. 47.1. Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 2013, p. 38 (English).

- ↑ Stephen Pow: The Last Campaign and Death of Jebe Noyan . In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Vol. 27 No. 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2017, pp. 31–51 (English).

- ↑ Carl Fredrik Sverdrup: Sübe'etei ba'atur, Anonymous Strategist . In: Journal of Asian History . No. 47.1. Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 2013, p. 41 (English).

- ↑ Paul D. Buell: Sübȫtei ba'atur . In: Igor de Rachewiltz et al. (Ed.): In the Service of the Khan: Eminent Personalities of the Early Mongol-Yuan Period 1200-1300 . Otto Harrossowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, p. 23 (English);

- ↑ Christopher P. Atwood: Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire . Facts on Files, New York, 2004, p. 282 (English).

- ↑ Stephen Pow: Climatic and Environmental Limiting Factors in the Mongol Empire's Westward Expansion - Exploring Causes for the Mongol Withdrawal from Hungary in 1242. In: Ed .: LE Yang: Socio-Environmental Dynamics along the Historical Silk Road . 2019, pp. 301–321. On-line.

- ^ Giovanni di Piano Carpini: The Story of the Mongols Whom We Call the Tartars . Translated by Erik Hildinger. Branden Books, Boston 1996, p. 65 (English).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sube'etai |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Subutai; Subotai |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Mongolian general |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1176 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mongolia |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1248 |

| Place of death | Mongolia |