Naqada culture

The Naqada culture , also called Negade culture , is a Copper Stone Age archaeological culture from the predynastic period of Egypt . The Naqada culture originated at the beginning of the fourth millennium BC. In Upper Egypt and spread northward to Lower Egypt over the course of 1500 years . It is divided into three periods that eventually lead to the early dynastic period of Egypt . These sections illustrate the constant social and technological change towards greater complexity that ultimately led to the establishment of the Egyptian state. The Naqada culture is often contrasted with the simultaneously existing Lower Egyptian culture , which was traditionally regarded as culturally and technologically inferior and which eventually merged with it.

The culture got its name from the Upper Egyptian city of Naqada about 45 km north of Luxor on the west bank of the Nile . There the British Egyptologist Flinders Petrie excavated a cemetery with over 2,000 graves in 1893, which he classified as predynastic for the first time based on their different burial customs and grave goods.

Naqada I (c. 4500 to 3500 BC)

The Naqada culture initially existed at the same time as the previous Badari culture , superimposed it and finally replaced it completely. The first period is also known as the Amra culture or Amratia after the El-Amra site . The development of the Naqada culture began with the desertification of the Sahara, which began around 3600 BC. Chr. Finally changed from the savannah to the desert . The semi-nomadic pastoral communities of the Badari culture living there moved to the fertile Nile valley and settled there. This population growth required new agricultural techniques to feed the population and encouraged the establishment of settlements that were later fortified. This development is reflected in the increasing variety of crops such as emmer , barley , flax and lentil as well as a greater number of livestock. In addition, the hunt and the gathering of wild plants such as tuberous sedge and the fruits of the doum palm supplemented the diet.

In the course of time, the resulting villages in the Upper Egyptian Nile Valley merged to form chiefdoms as forerunners of the later Gaue . From these later around eight proto-states emerged around the centers of Abydos , Abadijeh , Naqada, Gebelein , Hierakonpolis , El-Kab , Edfu and Elephantine , which were led by a local elite and were sometimes in sharp competition for resources and power. The coexistence of the proto-states can be seen in a regionally diverse material culture, with clear echoes of the Nubian A-group particularly in the south .

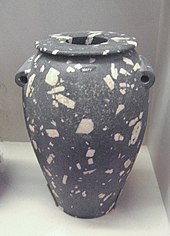

Much of the knowledge about the early Naqada culture comes from 85 known cemeteries and 50 settlements, with research having long been focused on the burial sites. Like those of the Badari culture, the deceased were buried in stool or embryonic positions with a view to the west, as well as grave goods in the form of ceramics and personal items. As in other cultures that existed at the same time, the settlements consisted of round rammed earth huts set into the ground , probably based on earlier nomad tents. The pottery of the Naqada I culture consists of red bowls and mugs made of Nile clay with a shiny black rim, the so-called "Black topped pottery". Typical decorative patterns are white and cream-colored geometric patterns. There is an increasing number of depictions of animals, hunting scenes, cult acts and fights. For the first time ships appear as a symbol of trade. Unlike in previous cultures, human figures also appear, both bearded men and women, who could be attached to ivory rods or pendants . Copper items are well known but rare.

Naqada II (c. 3500 to 3200 BC)

In the second phase, the Naqada culture spread northwards to the southern edge of the Fayyum Basin and began to assimilate the Lower Egyptian culture that settled there . Naqada II is also called Girga culture after the Girga site . The basis of life was now finally an agricultural production method with which food surpluses could be achieved. Social differentiation continued and urbanization continued to grow.

At the beginning of the Naqada II period, the number of proto-states had decreased to three, the centers of which were in Girga with its necropolis Abydos, Naqada and Hierakonpolis. At the head of these proto-states were probably hereditary monarchies , which drew their influence from the control of trade routes. Girga controlled the access to the Nile Delta and thus the trade with the lower Egyptian culture, Naqada the wadis to the gold mines in the Arabian desert and Hierakonpolis the trade with the oases in the Libyan desert and the Sudan . In the course of the conflict between the Upper Egyptian proto-states, one of them prevailed and founded a unified Upper Egyptian state, although it is unclear whether this role was assigned to Hierakonpolis or Girga-Abydos. A destroyed statue and other damage in the Hierakonpolis necropolis suggest violent conflict. This battle between the predynastic districts could be reflected in Egyptian mythology in the battle of the gods Horus and Seth , who had their most important places of worship in Hierakonpolis and Naqada. After the unification of Upper Egypt, the newly formed state expanded northwards, which after a short transition led to the end of Lower Egyptian culture. However, it is unclear whether this “ unification of the empire ” was achieved militarily, through economic and cultural assimilation or through migration of members of the Naqada culture to Lower Egypt.

The Naqada II period is well known from excavations of settlements and cemeteries, especially in the centers mentioned, but also further north. In the settlements, specialized handicraft businesses such as pottery, breweries and flint workshops as well as separate rulership and cult quarters emerged. In addition to the well-known round huts, rectangular houses made of adobe bricks appeared in Hierakonpolis for the first time , as they were to characterize later Egyptian cities. Growing social inequality is also evident in funeral customs. In the centers, spatially separate “elite cemeteries” are being created, in which members of the ruling class are buried in large graves, some of which have several chambers. Ceramics, jewelry, weapons and tools made from valuable materials serve as grave goods. Procedures that are regarded as the forerunners of embalming and rites of passage point to the later Egyptian cult of the dead . The pottery improved through the use of marl clay from the desert and professional manufacture. In addition to the familiar shapes, there is an ornament with wavy lines and spirals, some of which are based on Nubian and Levantine ceramics. There are also other clear indications of a pronounced trade within Upper Egypt in beer, ceramics and flint, as well as long-distance trade in special flint tools similar to the Gebel el-Arak knife and jewelry, which reached Lower Egypt, Nubia and the southern Levant. In addition to the highly developed flint processing , the number of copper tools is also increasing, with gold and silver being processed for the first time . Hunting scenes of hippos and animals of the desert such as Mendes antelopes dominate the visual language , which at that time only served cultic purposes. Ships are also shown more frequently and larger. In addition, militaristic victory scenes dominate. In a grave in Hierakonpolis there is a depiction of a king or chief of the proto-state slaying the enemy , a motif that was received over and over again until the end of ancient Egypt.

Naqada III (c. 3200 to 3000 BC)

This period differs from the previous one mainly in the grave goods of high-ranking people. During this period, the cities of Buto and Minschat Abu Omar were particularly populated.

Art and ceramics

Ceramics have been perfected more and more and for the first time finds from this period show hieroglyphic inscriptions, for example in the princely tomb of Scorpio I. (Uj).

literature

- Fekri A. Hassan: Nagada (Naqada). In: Kathryn A. Bard (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the Archeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18589-0 , pp. 555-57.

- Regine Schulz , Matthias Seidel (Ed.): Egypt. The world of the pharaohs. Könemann, Cologne 1997, ISBN 3-89508-541-3 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Agnieszka Mączyńska: Lower and Upper Egypt in the 4th millenium BC. The development of craft specialization and social organization of the Lower Egyptian and Naqada cultures . In: Studies in African Archeology . tape 14 , 2015, p. 66 f .

- ↑ Alice Stevenson: The Egyptian Predynastic and State Formation . 2016, p. 424 .

- ↑ Toby Wilkinson: Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt . Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-421-04346-7 , pp. 37 .

- ↑ Agnieszka Mączyńska: Who are the Naqadans? Some remarks on the use and meaning of the term Naqadans in Egyptian Predynastic archaeolog . In: Current Research in Egyptology 2016 . Krakow 2017, p. 44 .

- ↑ Patricia Spencer: Petrie and the Discovery of Earliest Egypt . In: Before the Pyramids. The Origins of Egyptian Civilization . Chicago 2011, p. 18 .

- ↑ a b c d e Sabine Kubisch: The old Egypt. From 4000 BC Until 30 BC Chr. Wiesbaden 2017, ISBN 978-3-7374-1048-9 .

- ↑ a b c d e Hermann Parzinger: The children of Prometheus . Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-66657-5 .

- ↑ Wilkinson 2012, p. 14.

- ^ A b c d Branislav Anđelković: Political Organization of Egypt in the Predynastic Period . In: Before the Pyramids. Origins of Egyptian Civilization . S. 28 f .

- ↑ Stevenson 2016, p. 431.

- ↑ Mączyńska 2015, p. 67.

- ↑ Parzinger 2016. The predynastic Naqada culture.

- ^ A b Alice Stevenson: Material Culture of the Predynastic Period . In: Before the Pyramids . S. 67 .

- ↑ Stevenson 2011, p. 73.

- ^ Stan Hendrickx: Sequence Dating and Predynastic Chronology . In: Before the Pyramids . 2011, p. 15 .

- ↑ Wilkinson 2012, p. 38 f.

- ↑ a b Stevenson 2016, p. 440.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Egypt. A story of meaning . Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 978-3-596-14267-5 , pp. 57 .

- ↑ Branislav Anđelković: Models of State Formation in Predynastic Egypt . In: Studies of African Archeology . tape 14 , 2006, p. 86 ff .

- ↑ a b Maczynska 2015, p. 76.

- ↑ Stevenson 2011, p. 77 ff.

- ↑ Asmann 1999, p. 47.